This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Debating Our Nation’s Origins: The 1619 Project vs. 1776 Unites

View Student Version

Standards

C3 Framework:D2.His.5.9-12. Analyze how historical contexts shaped and continue to shape people’s perspectivesD2.His.6.9-12. Analyze the ways in which the perspectives of those writing history shaped the history that they produced.D2.His.7.9-12. Explain how the perspectives of people in the present shape interpretations of the past.D2.His.8.9-12. Analyze how current interpretations of the past are limited by the extent to which available historical sources represent perspectives of people at the time.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

National Council for Social Studies:Theme 2 TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGETheme 5 INDIVIDUALS, GROUPS, AND INSTITUTIONS

National Geography Standards: Standard 17: How to apply geography to interpret the past.

Teacher Tip: Think about what students should be able to KNOW, UNDERSTAND, and DO at the conclusion of this learning experience. A brief exit pass or other formative assessment may be used to assess student understandings. Setting specific learning targets for the appropriate grade level and content area will increase student success.

Suggested Grade Levels: High School (9-12)

Suggested Timeframe: 1–2 weeks

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet, or mobile device; projector and screen for slides presentation and video viewing if providing face-to-face instruction; access to free web-based tools as noted.

Key Vocabulary

Aspiration - a hope, something to achieve, a goal

Complexity - something that is difficult, has many different parts or ideas to consider and resolve

Contradictions - ideas or statements that are against or opposite from each other

Discredit - attempt to make something seem less believable, to damage a source or person’s reputation

Enslavement - keeping a person in bondage, human slavery

Exploitation - treating someone unfairly to take advantage of them or their work, usually to benefit financially or to gain power or control

Liberation - freedom, to remove the bonds of slavery, control, debt, or obligation, to empower or free a person or group of people

Origin - the beginning, a starting point, one’s roots or ancestry, and homeland

Patriarchal - a society or system where men hold the most power

Victimization - an approach that says a person or a group of people has only had bad things happen to them; this approach ignores the resistance or accomplishments of that group

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tips

New American History Learning Resources may be adapted to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in partners or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs and Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge.

This Learning Resource guides students through an exploration of the complexity of studying history. Before you begin this lesson, it may be worthwhile to read Teaching History Is Hard on Bunk. To support you in this work, Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, developed several thinking routines that support students as they grapple with complex topics. It may be useful to review the resources in the Exploring Complexity Bundle before starting this activity with students. You may also consider going over Ways Things Can Be Complex with your students at the start of the lesson.

The Project Zero thinking routines offered in this Learning Resource include Parts, Perspectives, Me, Sticking Points, and Stories. These routines help students explore complexity in today’s complicated world by encouraging them to consider various viewpoints and reflect on their own connections and involvement with them. Additionally, the Save the Last Word for Me group discussion strategy from Facing History and Ourselves is included in this Learning Resource. The strategy and instructions have been adapted for synchronous and asynchronous remote learning, as well.

The final activity in this Learning Resource asks students to create a redacted poem using one of America’s founding documents. The Young Writers Project explains this style of poetry, sometimes called a “Found Poem”: Redacted Poetry--Explanation and Examples.

These Learning Resources follow a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience, or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

UPDATE: On November 2, 2020, The White House announced the establishment of the 1776 Commission by Executive Order. On January 18, 2021, The White House released the Commission's final report. On the morning of January 20, 2021, less than 48 hours after being posted, the Commission site containing the report was removed by the incoming new administration and archived by the National Archives. President Biden revoked the Commission and its work by Executive Order.

Teacher discretion should be used to determine whether the inclusion of the 1776 Commission report would add value to students' exploration of our nation's history. The historical accuracy of the report was widely criticized, as no academic historians were involved in its preparation and it did not include any citations. The document appeared to be a direct response to the perspectives shared in the 1619 Project and a culmination of the rebuttal by 1776 Unites that are explored in this learning resource.

Engage:

When and where does “American history” begin?

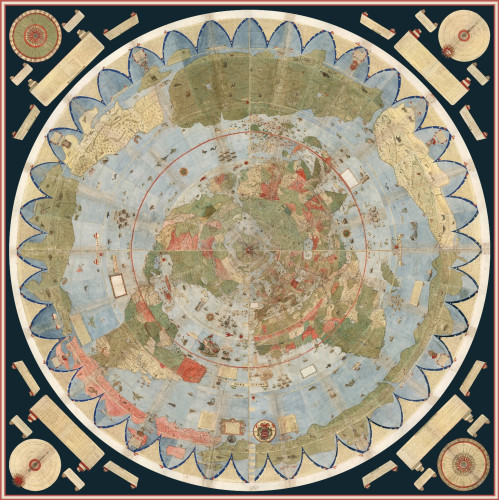

Take a look at The World According to the 1580s on Bunk. As you read, your teacher may ask you to complete Parts, Perspectives, Me to record your thinking.

- What are the various points that might be considered the beginning of “American history”?

- What perspectives can you look at this from? Different participants, users, makers, or storytellers? Different vantage points or physical positions?

- How are you involved? What connections can you make? What assumptions, interests, or personal circumstances shape the way you see it?

After you read the article, spend some time looking at the map’s images of North America. Keep in mind that this map was created in 1580, 27 years before the arrival of English settlers to Jamestown.

- What do you notice?

- What do you find surprising or interesting?

- What questions does this bring up for you?

- How do maps shape our perspectives?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

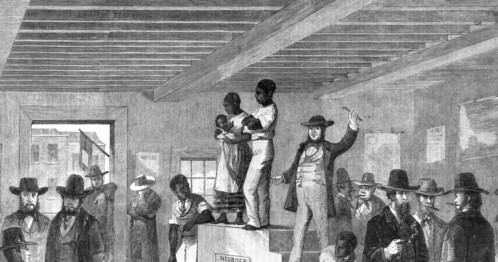

What role did human enslavement play in building modern America?

Listen to the BackStory episode 1619: The Arrival of the First Africans in Virginia. Your teacher may ask you to complete this Podcast Listening Guide as you listen.

- What information did you find surprising?

- What was especially interesting?

- Was there anything that troubled you?

Reflect on the following statements from people who were interviewed in this podcast episode:

“I want people to know that our history, our narrative, is not written in stone. That much of what we’ve grown up learning is incorrect in terms of these early years. It wasn’t neat, and it certainly wasn’t cleaned up the way that we present it in terms of our national narrative.”

“When Aretha Franklin died, people were not celebrating her dying, they’re celebrating her living. In the same way, you’re not celebrating enslavement, you’re celebrating those who persevered, those who endured.”

“And starting off here. Building the colonies that were getting started, and then over the years what we’ve done. This is the birthplace; this is the beginning. And the contributions have started right here. That’s significant to me.”

“I think the arc of history is important… But what I try to convey to folks is that it’s not just an African American story, it’s really an American story, and we need to merge all these stories into one. Let’s not be afraid to have these conversations about slavery and racism… We’re literally just learning how to be a country, and I think we all just need to figure this thing out.”

Choose one quote from above and compose a response to that person, based on your thoughts and reflections after listening to the BackStory episode.

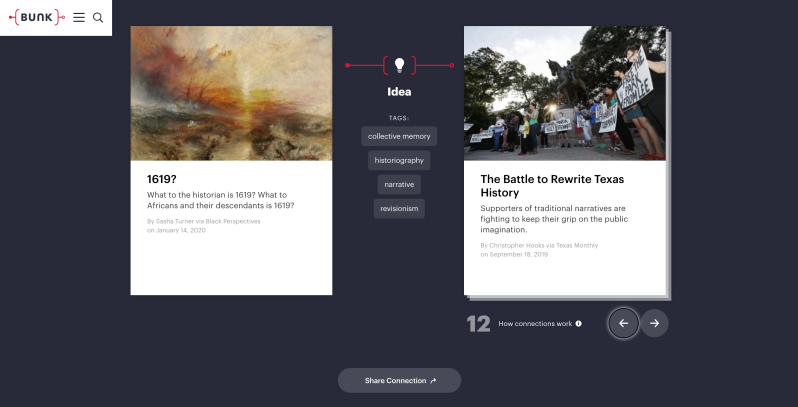

Next, check out the article 1619? on Bunk. Before you read, notice the stack of cards to the right of the article. There are icons there that symbolize different types of connections you can make using Bunkhistory.org to learn more about history and current events. Take a few minutes to explore the cards and icons. You will notice that each icon leads you to a new stack of cards. To learn more about these, read How Connections Work.

Choose one connection that looks interesting, challenges your thinking, or presents a new point of view and share it with your teacher or class by clicking on “Share Connection," using a collaborative document, email, or through social media as directed by your teacher.

Now, go back and read 1619? Click the blue button “View on Black Perspectives” to read the entire article.

- After you read, choose one statement or sentence from the article that stands out to you.

- Write the statement down, along with an explanation of why you chose it. If you need help coming up with a reason it stands out to you, think about what the sentence means to you, whether you can connect it to your own experiences or beliefs, or whether you can relate it to something that has happened in history or is happening now.

Your teacher will assign you to a small group of 3-4 students to share your selection in a Save the Last Word for Me discussion activity.

- Meet with your group and choose the order in which you will share.

- Choose one group member to be the timekeeper.

- The first student should share the statement they selected, but NOT their explanation.

- The other members of the group will discuss the statement that was shared for 3 minutes. You might talk about what the quote means or why the words might be important.

- After 3 minutes, the first student should share their explanation.

- Repeat this process for every student in the group.

After finishing your group discussion, reflect on the activity.

- What went well during the conversation? What was challenging?

- How did the Bunk connection you explored change your thinking or show you a new way to think about this part of history?

- Connect: How did the ideas and information in the reading and your discussion connect to what you already know about this enslavement in the Americas?

- Extend: How did this activity extend or broaden your thinking about enslavement in the Americas?

- Challenge: Did this activity challenge or complicate your understanding of this topic? What new questions does it raise for you?

After engaging in both of these activities, reflect on the questions asked by Frank Harris as he sought to commemorate 1619: “If you had the opportunity, what would you say to the first enslaved African? What would be your words to that person?” Share what you would say to that person.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

How should we tell the story of America’s beginnings?

“Historical understanding is not fixed; it is constantly being adjusted by new scholarship and new voices. Within the world of academic history, differing views exist, if not over what precisely happened, then about why it happened, who made it happen, how to interpret the motivations of historical actors and what it all means.”

In August of 2019, the New York Times published The 1619 Project, a special issue of their magazine. The editor explained their reasons for publishing this project: “The goal of The 1619 Project is to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year. Doing so requires us to place the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country.”

Within a few months of publication, some historians and politicians expressed criticism of The1619 Project, arguing that it went too far in an effort to “rewrite history.” In December 2019, The New York Times published a letter from five historians who critiqued the project, along with their own response. In February 2020, another group of critics published Sorry, New York Times, But America Began in 1776 as a rebuttal to the suggestion that 1619 should be considered our nation’s birth year. They launched 1776 Unites as “an assembly of independent voices who uphold our country’s authentic founding virtues and values and challenge those who assert America is forever defined by its past failures, such as slavery. We seek to offer alternative perspectives that celebrate the progress America has made on delivering its promise of equality and opportunity and highlight the resilience of its people.”

In May 2020, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, professors Eddie Glaude Jr. and Leslie M. Harris and Pulitzer-winning columnist Clarence Page came together to discuss the debate over The 1619 Project.

As you listen to each contributor, keep track of how they agree or disagree about the facts, values, interests, and policies of historical record using this Sticking Points graphic organizer.

What is at the heart of the disagreement between The 1619 Project and 1776 Unites? Explore both projects and record points of agreement and disagreement on your Sticking Points notes.

Next, read one author’s perspective on the conflict: The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts. Click the blue button, “View on The Atlantic,” to read the entire article. You have the option to listen to a read-aloud version of the article when you have it open on The Atlantic site. As you read, continue to add to your Sticking Points notes.

“Underlying each of the disagreements in the letter is not just a matter of historical fact but a conflict about whether Americans, from the Founders to the present day, are committed to the ideals they claim to revere. And while some of the critiques can be answered with historical fact, others are questions of interpretation grounded in perspective and experience.”

After reading, take a moment to reflect on your current thinking about The 1619 Project.

Next, look through the 1619 Project Bunk tag. Choose one article you would like to read.

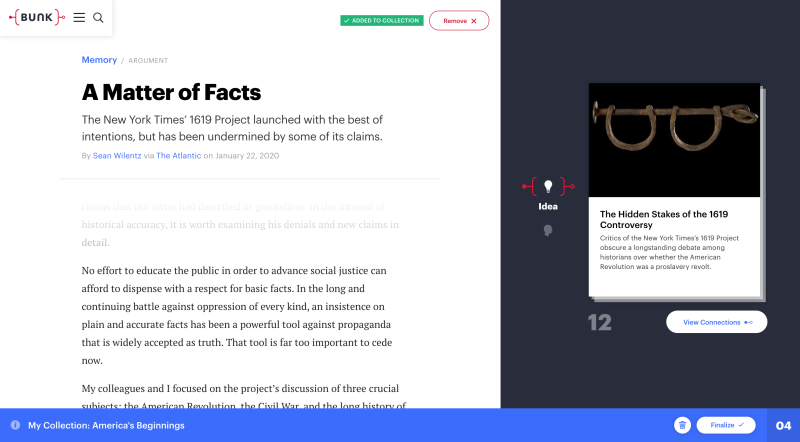

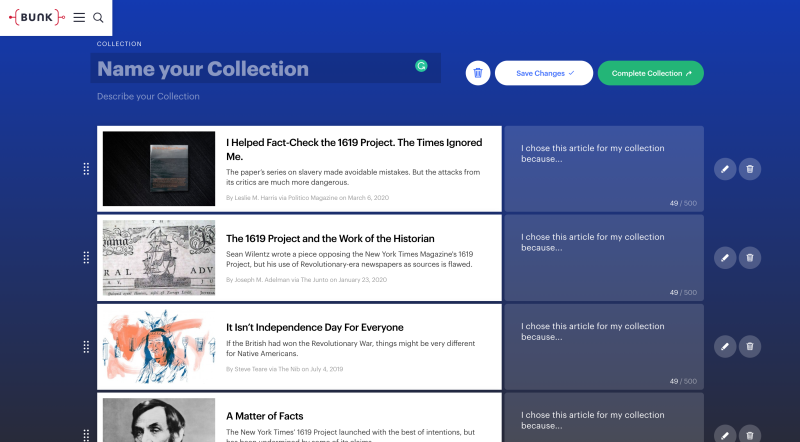

Explore the connections to create a Bunk collection of 3-5 articles that help explain your perspective on how we should tell the story of America’s beginnings.

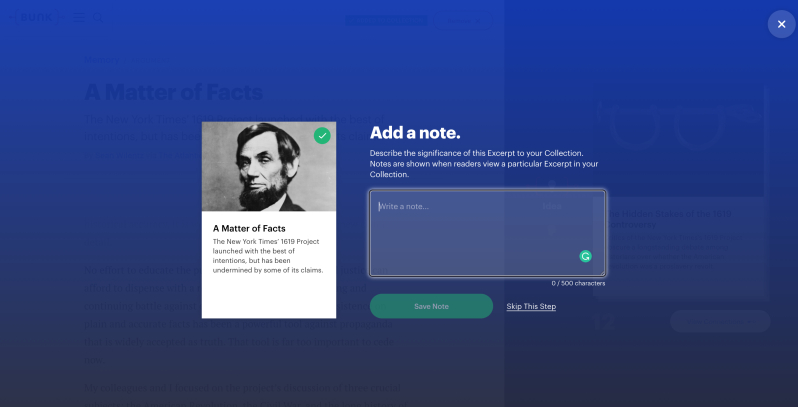

When you find a thought-provoking Excerpt or Original, click the Add to Collection + button. Include a note describing the significance of the piece to your Collection. (Notes are shown when readers view a particular Excerpt or Original from your Collection. Your note should explain why you chose to include this article in your collection and how it helps to tell the story of America’s beginnings.

While continuing your search, add more content to your Collection by clicking the Add to Collection + button on other Excerpts or Bunk Originals. Keep in mind: Collections are stored in your browser using cookies until they’re completed, so if you exit your browsing session or clear your cookies before completing, your Collection may be lost.

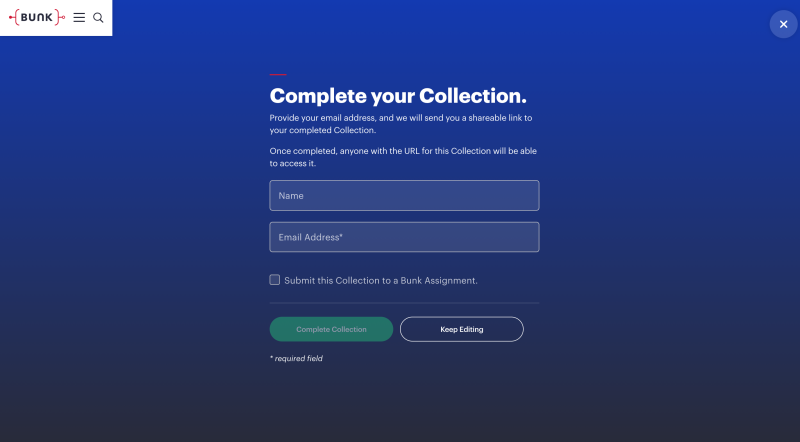

Once you’ve finished building your Collection, finalize your Collection by giving it a name and an optional description, and then click the Complete Collection button. Your teacher will explain how to share your collection with them.

Finally, share a reflection about the origins of U.S. history using the following prompt:

- I used to think … , but now I think …

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

Which parts of U.S. history should students be required to learn about? Are there parts that should be left out?

History education is complicated. How much of that complexity should students learn about in school? Listen to this short clip on Bunk: Americans Aren't Just Divided Politically, They're Divided Over History Too

Next, read Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories on Bunk. Use the View Connections button to find other related content to this excerpt. Turn and talk to an elbow partner, or if working remotely your teacher will provide an opportunity for your to share an interesting connection based on your exploration of this topic on Bunk using the chat feature if working together in breakout rooms or via video chat, or using a collaborative document like Google Docs or Slides.

Next, return to the original excerpt of "Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories." Click the blue button “View on The New York Times” to read the entire article and see close-up comparisons of the two textbooks.

Look at your own textbook or class materials (both print and/or online) for this class. What is the story being told about the history of the United States? Use this Stories graphic organizer to consider how history has been presented, what has been left out, and how you might want to present America’s story.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

How do we choose to remember our history?

The 1619 Project included original works of poetry and stories from 16 writers. Whether or not you agree with the historical evidence presented in The 1619 Project, this section shows us a powerful approach to telling the story of history.

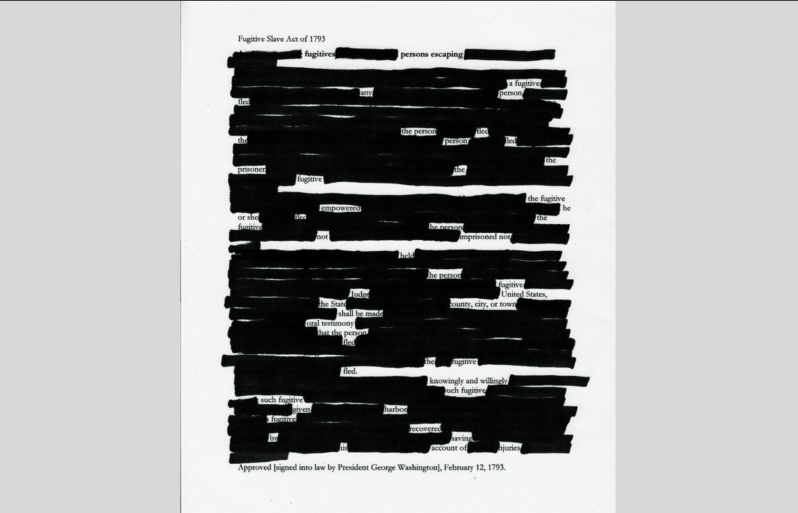

Look at the fourth poem on the site, called Feb. 12, 1793. This style of poetry is called a redacted, found, or blackout poem. It is created by covering up all of the words of a document except for those that tell the story you want to present to your readers. Often, that story changes the message of the document, but it shows the meaning you want readers to take away from it. For this poem, Reginald Dwayne Betts used the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 as his starting point.

Watch poet Austin Kleon create the redacted poem No Angel using a clipping from the newspaper.

When you create your own redacted poetry, it's helpful to pay attention to which words jump out at you or make an emotional impact. Find a word near the beginning of the document that is meaningful to you. From there, skim through the document to find other words that connect to the first. Remember, you’re trying to share a message that may or may not be what the original author intended. Instead, you’re attempting to reveal a hidden meaning in the words. These types of poems don't have to be grammatically correct or follow a rhythm. They work best when they are free-flowing and full of interpretation. It might help to start with a pencil, underlining words you may end up using, before blacking out the rest of the document.

Here is a collection of founding documents that are part of United States history. Choose one document from this collection (or another on the site) to create your own redacted poem. You can use a black marker or a digital blackout tool on your device.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

We would love to see your work - please share if your teacher or a trusted adult permits. You may email us at editor@newamericanhistory.org or share via social media (links on our pages). Be sure to tag us as you share!

Citations:

"The 1619 Project." The New York Times. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html

"A Roundtable Discussion On The Times’ 1619 Project | Morning Joe | MSNBC." Video, 23:28. YouTube. Posted by MSNBC, May 14, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2020. https://youtu.be/TZthCKVIw34.

“About the 1776 Unites Campaign.” 1776 Unites. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://1776unites.com/

Betts, Reginald Dwayne. "Feb. 12, 1793." The 1619 Project. Last modified August 14, 2019. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/african-american-poets.html.

Breen, Benjamin. “The World According to the 1580s,” Bunk, April 17, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/4110

Bunk History. New American History. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/tags/ideas/4946.

Goldstein, Dana. “Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories.” Bunk, January 12, 2020. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/5430.

Kleon, Austin. “No Angel.” Austin Kleon, August 29, 2014. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://austinkleon.com/2014/08/29/no-angel/

Lloyd, Gordon, ed. "The American Founding." Teaching American History. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/collections/the-american-founding/.

Morning Edition, Rachel Martin, and Jill Lepore. "Americans Aren't Just Divided Politically, They're Divided Over History Too." Bunk, May 23, 2017. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/378.

"Parts, Perspectives, Me" Project Zero. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Parts%20Perspectives%20Me%20-%20for%20exploring%20complexity.pdf.

Reilly, Wilfred. “Sorry, New York Times, But America Began in 1776.” Bunk, February 17, 2020. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/5593

"Save the Last Word for Me." Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/save-last-word-me.

"Save the Last Word for Me (Remote Learning)." Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/save-last-word-me-remote-learning.

Serwer, Adam. “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts.” Bunk, December 23, 2019. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/5365

“Sticking Points.” Project Zero. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Sticking%20Points%20-%20Exploring%20Complexity.pdf

“Stories.” Project Zero. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Stories%20-%20Exploring%20Complexity.pdf

Turner, Sasha. “1619?” Bunk, January 14, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/5444

“VA Foundation for the Humanities | 1619: The Arrival of the First Africans in Virginia” BackStory. Virginia Humanities, August 23, 2019. https://www.backstoryradio.org/shows/1619-the-arrival-of-the-first-africans-in-virginia/.

“We Respond to the Historians Who Critiqued The 1619 Project.” The New York Times. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/20/magazine/we-respond-to-the-historians-who-critiqued-the-1619-project.html

"Why We Shouldn't Forget that U.S. Presidents Owned Slaves." Video, 03:37. YouTube. Posted by PBS NewsHour, February 2, 2017. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://youtu.be/ohB8UfLd93M.

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc