This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

American Visions: Blubber Boom

Key Vocabulary

Archaeologist - a person who studies human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains

Ballad - a narrative poem or song that tells a story, often passed down orally and characterized by simple language.

Contemporaries - a person or thing living or existing at the same time as another

Crankie - a handmade scrolling visual storytelling device that uses scrolled paper on spools or dowels. The scroll moves by being “cranked” as a story is told/sung.

Demographic - a particular section of a population

Dowels - cylindrical rods, typically made of wood, used to reinforce and/or join parts

Embellish - make something more attractive by the addition of decorative details or features

Encapsulates - to express or summarize something clearly and concisely

Exercise Book - an 18th-century term to describe a book where students copied down notes and other work, typically used for exercises related to learning to read and write

Field Experience - a practical learning opportunity outside of the classroom that allows learners to apply theoretical knowledge to real-world settings

Harvested - to have gathered/collected a natural resource for human use

Moving Panorama - a 19th-century-style painting, often accompanied by music and narration that moved on scrolls, intending to encircle and immerse viewers in the scene/setting

Pantomime - a type of dramatic or dance performance where expressive movements and facial expressions tell a story

Primary Source - an original document or artifact created at the time of an event or by a person directly involved, providing first-hand evidence or eyewitness accounts

Realistic - having or showing a sensible and practical idea of what can be achieved or expected

Scrolls - long, continuous painted canvases that are wound on spools and unwound to simulate movement and tell a visual story

StoryMap - a digital tool that combines interactive maps with narrative text, images, and multimedia to present spatially-driven stories

Travelogue - a written or visual account of a person’s experiences, thoughts, and observations while traveling to different places

Walking Tour - a guided or self-guided exploration, on foot, typically focused on historical, cultural, and architectural highlights of a community, neighborhood, or portion of a city/town

Read for Understanding

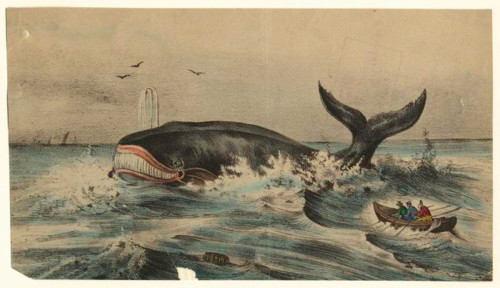

The early nineteenth century was the height of the whaling industry, fueling the growth of many New England cities and touching the lives of a diverse cross-section of Americans, including free African Americans and immigrants. It also inspired a wide array of American art and literature. This Learning Resource invites you into the fascinating and dangerous world of American whaling.

Engage:

Why Whales?

In an excerpt from the BackStory podcast archives, Yale historian Joanne Freeman calls whales “nothing less than the chemical factory of the 19th century.” When considering early booming American industries, one might not immediately jump to the largest mammals on Earth. But for many locations along the coast of New England, whales and whale products found their way into many aspects of life. To begin your investigation, you’ll create a Concept Map that explores four areas of life touched by the whaling industry- economic life, artistic life, demographic life, and domestic life. (Your teacher may print a copy for you, or create and use a digital copy as directed by your teacher.)

Begin by listening to an excerpt from the BackStory episode, ‘Thar She Blows,’ called Built on Greasy Luck.

Afterwards document any thoughts in the areas/questions on the Concept Map and share in small groups as directed by your teacher.

After listening access the primary source set called American Whaling Industry from the Digital Public Library of America. Choose one primary source that your group thinks best encapsulates the whaling industry and touches on as many areas of life from your Concept Map.

In presenting your group’s primary source you may choose to use the following sentence starters/prompts:

- We chose this because….

- It comes from….

- We felt that it best illustrates the whaling industry because of….

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

What types of Americans were involved in the whaling industry?

If there was a centerpoint of the American Whaling industry in the 1840s-1850s it was probably New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Historian Ed Ayers visited New Bedford as part of an American road trip in 2023. Ayers wrote about and mapped his experience in a Travelogue, paying special attention to many of New Bedford’s residents and their connection to whaling.

Read Ayers’ Travelogue on Bunk. As you read, think about the following questions:

- Who originally founded New Bedford, and what might that tell us about the culture of, and life in, the city?

- What kinds of opportunities did the whaling industry offer to people in New Bedford that might not be available to them elsewhere?

- Who are some specific people mentioned in Ayers’ travelogue who passed through or lived in New Bedford and were part of the whaling industry there?

- What influence did they have on American life beyond New Bedford?

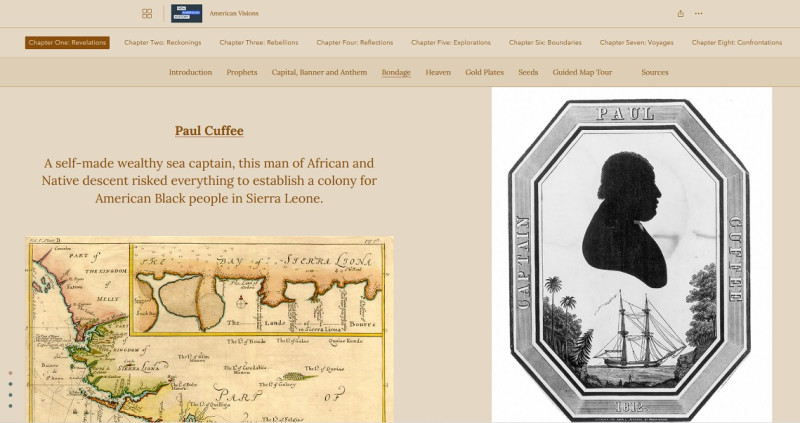

Next, turn to the story of a Black whaler as told by Emmanuel College history professor Jeffery Fortin in this segment from the BackStory podcast archives, Paul Cuffe, Black Whaler and Self-Made Man. Fortin begins by describing the experience of people of color while working on whale ships.

After listening to Fortin tell Cuffe’s story explore this StoryMap from Ed Ayers’ book and companion site, American Visions. As you learn about Cuffe’s contemporaries think about what made his advancement so far possible at the time.

*Note that Cuffe’s name is spelled differently across various sources - “Cuffee” and “Cuffe.”

After listening to the BackStory excerpt and exploring the StoryMap, collect your reflections on this I used to think…Now I think… graphic organizer.

Cuffe was born in Buzzard’s Bay, Massachusetts, to a formerly enslaved man and a Wampanoag woman. After teaching himself to read and write through his father’s exercise book, Cuffe set his sights on whaling as a way to advance in 18th-century America. As you listen to Professor Fortin describe Cuffe’s story consider the question that Ayers poses:

“The question at the heart of the Black whaling experience: was whaling a means of escape or further imprisonment?”

Prepare to participate in a Barometer Discussion as introduced by your teacher. One end of the barometer represents the position that whaling was a “means of escape.” The other end of the continuum represents the position that whaling was “further imprisonment.” Using Paul Cuffe’s life as a case study, place yourself anywhere along the continuum. Consider crafting your thoughts in the form of a Position Statement.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

How did Americans in the 19th century come to know and understand distant locations and events?

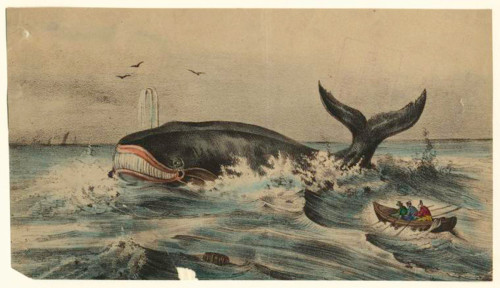

In the first half of the nineteenth century Americans had little knowledge of what it was actually like to be on a whaling voyage. There were few ways to closely understand and experience far-off locations in general. Human beings were decades away from widespread electricity and a century away from technology such as radios, which would bring the outside world into their homes. Yet this period was also an era of popular entertainment marked by illusion, spectacle, the exotic, and the unknown. The traveling circus, pantomimes, and public theaters were just some forms of popular entertainment during this period that allowed Americans to “experience” far-off lands. One such method of immersing people in a particular time and place was the moving panorama. These were large paintings set up on scrolls, often accompanied by music and narration. Moving panoramas moved across American towns and cities, in some ways they were the precursor to early motion pictures.

Watch this video about a moving panorama that was restored by the New Bedford Whaling Museum (NBWM) :

After watching, turn-and-talk to an elbow partner to discuss the following questions/prompts.

- What role did the moving panorama play in 19th-century America?

- The panorama traveled around and was viewed by various audiences. In the video, Dr. Connett, former Chief Curator of the NBWM, describes the moving panorama as a way for people to “see” other parts of the world. Why might they like this format?

- What sort of people do you think would be in the audience?

- When it comes to wear and tear on historic pieces of art, what unique challenges face the moving panorama compared to other paintings?

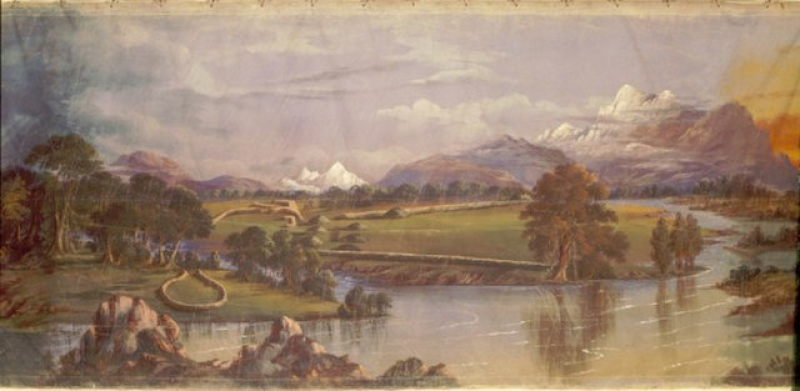

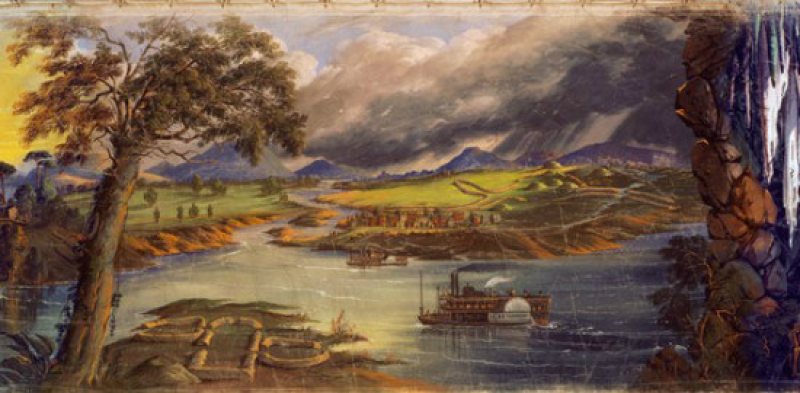

In another similar example, beginning in 2011, the St. Louis Art Museum began restoring one such work: the “Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley.”

That project is documented in this three-minute film from ‘Who Else Loves Art?’

After watching, turn-and-talk to an elbow partner to discuss the following questions/prompts.

- In the video, Claire Winfield, Associate Painting Conservator at the St. Louis Art Museum, describes this painting as a “wonderful example of our shared history.” What, specifically, about the moving panorama makes it an example of “shared” history?

- The panorama was created by an artist but narrated by an archaeologist. What might that tell us about the scenes depicted in the moving panorama?

Now spend a few minutes exploring the St. Louis Art Museum’s digital exhibit of the “Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley.” Notice that you can select individual panels of the panorama and zoom in closely for a detailed view. As you investigate the moving panorama, keep in mind Winfield’s words: “a wonderful example of our shared history.” How might you describe that shared history as illustrated in this particular moving panorama?

Use the Step In/Step Out/Step Back thinking routine, discussing with three different partners, to consider the role and significance of moving panoramas in 19th-century America:

- Step In: Based on what you know right now, what did moving panoramas offer 19th-century Americans that they would not have access to otherwise?

- Step Out: What else would you like or need to learn about moving panoramas to further understand their role in American life?

- Step Back: Given your exploration of moving panoramas so far, how might they be stronger examples of “shared history” compared to standard paintings?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

How realistic and/or embellished a picture of whaling did the moving panorama provide Americans in the 19th century?

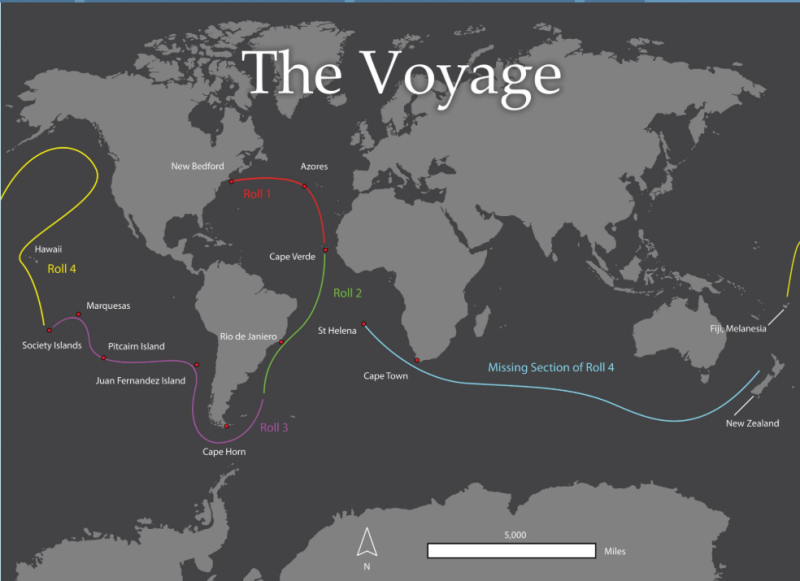

In 1848, two Massachusetts men - Caleb Purrington, a sign-maker, and Benjamin Russell, a painter - unveiled their Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage ‘Round the World. It is the longest painting on record, measuring 1,275 feet in length and 8 feet in height. Broken into 4 spools (5 originally, but the fifth section was lost over 100 years ago), Purrington and Russell’s work takes viewers from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to the Azores, Cabo Verde, Rio de Janeiro, and various locations in the Pacific.

First, examine this digital StoryMap of the whaling voyage as outlined on the digital Grand Panorama. Create a list of questions about the voyage as a whole, giving special consideration to the fact that it was 1848.

Next, divide into four groups, either on your own or as directed by your teacher. Groups should be relatively similar in terms of size. Each group will do its own deep dive into a specific role of the panorama.

Select the second tab after ‘Introduction’ called ‘Voyage’. Read your role’s associated section of The Voyage on the digital Grand Panorama, and discuss the questions below for your particular section of the voyage/panorama. (Use the menu at the top of the StoryMap to navigate to this section).

Roll 1: New Bedford/Buzzards Bay/The North Atlantic/The Azores

- How would you describe the level of activity in New Bedford as portrayed by the artists?

- What can you tell about the kinds of job opportunities that existed in New Bedford?

- What do the scenes from the Azores suggest about which people and countries were involved in whaling?

Roll 2: Cape Verde/Rio de Janiero, Brazil

- How would you describe the relationship between whalers and wildlife based on this section?

- In the scene with the ship Trident, what do you notice about how whales were processed once caught?

- What do the scenes from Rio de Janeiro suggest about class and labor in Portuguese-controlled Brazil?

Roll 3: Cape Horn/Juan Fernandez Islands/Pitcairn Island/Marquesas/Society Islands

- Russell’s painting of the ship sailing westward around Cape Horn is said to be his “finest achievement in formal marine painting.” What specific elements in this scene do you think best support that claim?

- What do the small details Russell depicted on Pitcairn Island - “the Nose” rock, the banyan tree, and protruding timbers - suggest about how widespread the whaling industry was by 1848?

- How would you describe the relationship between native peoples and whalers based on the Society Islands portion of the panorama?

Roll 4: Hawaii/Northwest Coast/Fiji

- What do you think the artists thought of the islands and inhabitants based on how they portrayed Kealakekua Bay?

- How might you describe the process of whaling based on the whaling scene and stove boat scene in the Northwest Coast portion?

- Why do you suppose that Russell didn’t portray anything directly related to whaling in the final scene?

Jigsaw

Next, re-shuffle the groups so there is a representative from each roll of the panorama in the new groups. This strategy, sometimes called “Jigsaw,” allows team members to share their thinking across smaller breakout groups.

Each group member should choose one scene from their roll of the panorama to share with the other group members. As you guide others through the scene, provide the following information:

- Location within the larger voyage

- What’s happening in the scene

- How is whaling as a profession/pursuit portrayed

- How “Realistic” or “Embellished” would you classify the scene?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

How might a moving panorama deepen our understanding of our communities and their history?

We’ve explored how moving panoramas exposed 19th-century Americans to far-off, and often exotic, locations. But they also allowed viewers to understand what life looked like, and even sounded like. This learning experience will allow you to capture your own community and its history on a moving panorama and share it with an authentic audience.

Step #1: Create small groups or break into ones predetermined by your teacher. Each group will be creating a portion of a moving panorama. You’ll be venturing out on a Walking Tour of your community with this group and ultimately be creating a piece of a moving panorama. Either your teacher or your group will determine the route of your tour. Google Maps can be a valuable resource as you plan the route. Once your group determines the route, work together to complete the first two steps of a KWL Chart to determine what you already know and want to learn about your particular route.

Step #2: Read through and have on hand copies of the Walking Tour Checklist. of items to look for, document, and potentially include on your group’s section of the moving panorama.

Step #3: Prepare to head out on your Walking Tour. This might take place during a school day or be assigned outside of school hours. Either way, think of it as a “field experience” in which your group is moving through a designated route of your community. The goal is to capture sights, sounds, and observations that help deepen your understanding - and eventually an audience’s understanding - of your community. Items you’ll want to bring on the tour include a notebook, pens/pencils, and a device to capture images and sounds (camera, smartphone, audio recorder, sketches). Note: Your teacher will review your school’s Acceptable Use policy for smartphones/images.

Once back from your Walking Tour, plan to sketch out your group’s portion of the moving panorama. Your teacher will provide you with several pieces of large craft paper from a roll (~18-24” wide).

Step #4: Plot and sketch out the scene on your group’s paper based on the observations and documentation from the Walking Tour. Because you’re creating a portion of a moving panorama, it might help to look at some 19th-century ones for ideas and inspiration. You’re already familiar with the Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley and the Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage ‘Round the World. A variety of other panoramas can be accessed here as well. Remember that the moving panorama your class is creating is meant to help viewers gain a deep understanding of the history and culture of your community. It’s meant to be large, encompassing, and provide a snapshot of life there.

Notice scenes with modes of transportation like this one on the Mississippi River:

Or ones depicting weather and people like this one:

Step #5: When your group is finished and satisfied with your portion of the moving panorama, it’s time to put them together. Find a large space like the floor of a gymnasium or parking lot (weather permitting) and lay all of the portions out. Discuss and decide as an entire class what order makes the most sense. If groups depicted different historical scenes, consider making the panorama chronological. If groups depicted everyday scenes based on what they saw on the Walking Tour, consider making it geographically accurate, so viewers follow an actual route through the community.

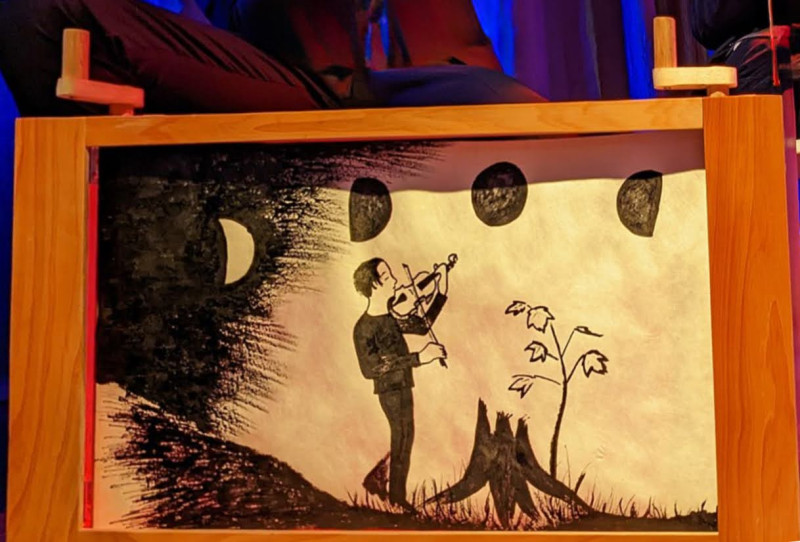

Step #6: Once the panorama is arranged and assembled, your class can set up the “moving” aspect of the panorama. Recently, these have come to be known as “crankies” and have become a popular form of folk art.

You can set up your group’s panorama to move with some wooden dowels, masking tape, and with a simple four-sided box. Check out this video on how to load the panorama into a crankie box.

Step #7: Depending on your class’s available time and capacity, you might consider organizing a showing of your moving panorama. In addition to presenting it as a crankie, some members of the class might write a narrative to go along with the panorama. Local libraries or historical societies typically have staff members and large archives of historical materials that are a good resource for writing a narrative to pair with the panorama. Additionally, your class might consider setting the panorama to music. You might play pre-recorded music or even perform with live musicians.

The BackStory archives episode on whaling has a segment, Songs of the Sea, that features history, characteristics, and examples of sea shanties that made their way onto 19th-century whaling voyages. You might consider adopting the call-and-response format into an original song inspired by your group’s section of the panorama.

Crankies/panoramas have been popularized by musicians who sing traditional ballads. View this video from singers Anna Roberts-Gevalt and Elizabeth LaPrelle performing "Golden Vanity" at Music City Roots Live From The Factory on September 28, 2016.

Similar to the way 19th-century Americans were immersed in the worlds of whaling and the Mississippi Valley, strive to immerse your audience in the world of your local community.

We would love to see your crankies! Your teacher may share them with us via email: editor@newamericanhistory.org.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

Archive, BackStory. 2019. “Songs of the Sea.” BackStory. https://backstory.newamericanhistory.org/episodes/thar-she-blows-again/1/Archive, BackStory. 2019. “Thar She Blows.” BackStory. https://backstory.newamericanhistory.org/episodes/thar-she-blows/2/

Ayers, Ed. 2023. “Chapter One: Revelations.” American Visions StoryMap. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/collections/684a16d2ddcb44609011f211e21c6596?item=1

Colson, Nicole S. “Crankie Revival Is Nod to Theatrical History.” The Keene Sentinel, January 12, 2018. https://www.keenesentinel.com/elf/crankie-revival-is-nod-to-theatrical-history/article_d98ba022-f7a1-11e7-964c-f773e4fa01e4.html Accessed September 29, 2025.

Digital Public Library of America. 2025. “The American Whaling Industry.”. https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-american-whaling-industry#tabs

Egan, John J. (1810–1882) “Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley.” St. Louis Art Museum. https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/841/

Ellis, Leonard B. (1876) with O.H. Bailey & Co. and C.H. Vogt (Firm). “View of the city of New Bedford, Mass., 1876.” Library of Congress. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://www.loc.gov/item/2005628469/ The Crankie Factory. YouTube. 2014. “Loading a Paper Scroll Into a Crankie Box.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gO7BAkrmYuE

Facing History & Ourselves. Teaching Strategies Collection. ‘Jigsaw’ pedagogy. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/jigsaw-developing-community-disseminating-knowledge Accessed September 29, 2025.

Google Maps. "Description of Map or Directions." Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.google.com/maps

Laprelle, Elizabeth. ‘Anna & Elizabeth / Crankies’. From ’Old Songs and Ballads’. Website. https://elizabethlaprelle.com/projects/anna-elizabeth-crankies

Mystic Seaport Museum. (2021-2022) ‘Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage ‘Round the World’ https://mysticseaport.org/explore/exhibits-3/the-grand-panorama/ Accessed September 29, 2025.

Roberts-Gevalt, Anna and Elizabeth LaPrelle . 2016. “The Golden Vanity.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkHF9qlOxgw&list=RDZkHF9qlOxgw&start_radio=1 Accessed September 22, 2025.

St. Louis Art Museum. Digital Exhibit of the “Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley” https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/841/ Accessed September 22, 2025.

Truman, Sue. 2019. “Moving Panorama History & Related Art.” https://www.thecrankiefactory.com/115034629.html

‘Who Else Loves Art?’ channel. YouTube. 2025. “Saving Art History: Restoring a 19th Century Moving Panorama.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DMcsKhPOYcA

Wikimedia Commons. 2013. “Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Panorama+of+the+Monumental+Grandeur+of+the+Mississippi+Valley&title=Special:MediaSearch&type=image

Wikipedia. “The Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage Heard 'Round the World.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Grand_Panorama_of_a_Whaling_Voyage_%27Round_the_World Accessed September 29, 2025.

Wikipedia. ‘Panoramic Painting’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panoramic_painting Accessed September 22, 2025.