This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Seizing Freedom: Do No Harm

Read for Understanding

These learning resources explore the history of latrophobia and medical mistrust within the Black community. Some of the resources are of a sensitive nature, and some language and content may be challenging for some learners more than others. You and your teacher will work together, along with your classmates, to have open and honest conversations about some of these sensitive topics around race and past historical atrocities.

Key Vocabulary

Autopsy - a post-mortem (after death) examination performed by a doctor to determine the cause of a patient's death

Chattel slavery - the enslaving and owning of human beings and their offspring as property, able to be bought, sold, and forced to work without wages

14th Amendment - an amendment added to the U.S. Constitution after the American Civil War, granting citizenship rights to all persons born or naturalized in the United States.

Discrimination - unfair treatment of people based on their race, gender, age, etc.

Ethical - upholding important shared values and principles

Eugenics - a branch of scientific inquiry normalized in the early 20th century that advanced the idea that some human groups are superior to others, and advocated for the groups deemed inferior to be eliminated from the population

Genome - the complete set of genes or genetic material present in a cell or organism that determine how that organism develops

Humane - valuing other living creatures and people;, showing kindness, sympathy or consideration for others. (Antonym Inhumane - placing no value on the lives of others, cruel and without care or empathy)

Imbecile - an antiquated and offensive term used to describe people with intellectual disabilities

Jim Crow laws - state and local laws that enforced segregation of races

Latrophobia - fear of a healer or doctor

Lynching - the murder of an individual who has not received any due process, often at the hands of a vigilante group or mob

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) - a white supremacist group founded in 1865 to intimidate African Americans from voting, holding public office, owning competitive businesses, or asserting themselves politically or financially

Post mortem - medical term meaning “occurring after death.”

Racial Hygiene - an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, and taken to extremes in Nazi Germany, that sought to prevent interracial marriage or relations, with the goal of creating the human equivalent of purebred animals

Segregation - the practice of race-based separation in public spaces including schools, public transportation, restroom facilities, and neighborhoods

Sterilize - to surgically alter reproductive organs to prevent future pregnancies

Subjugate - to take control of or dominate a person’s life

Sundown Towns (also known as Sunset Towns, Gray Towns, or Sundowner Towns) - all-white communities that restricted or forbid the presence of African Americans after the sun went down

Syphilis - a bacterial infection spread through sexual intercourse, and treatable with antibiotics

Plessy v. Ferguson - A Supreme Court ruling that upheld the legal separation of facilities for different races, and established the “separate but equal” doctrine for many years

Polio (poliomyelitis) - a viral disease that attacks the spinal cord and damages the nervous system. Polio affects mainly children and can lead to paralysis or deformed limbs.

Racial terror - the threat or act of violence to intimidate and cause fear to people of another race

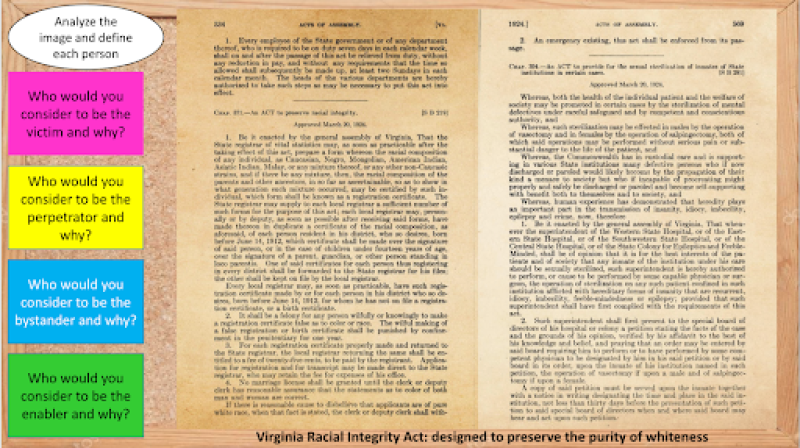

Virginia Racial Integrity Act - law establishing a legal definition of a white person as one “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.” The purpose of the law was to prohibit intermarriage between whites and non-whites and to protect the “purity” of the white race.

Virology - the study of viruses that affect humans, animals, and plants

Engage:

Why do some African Americans mistrust doctors and medical professionals?

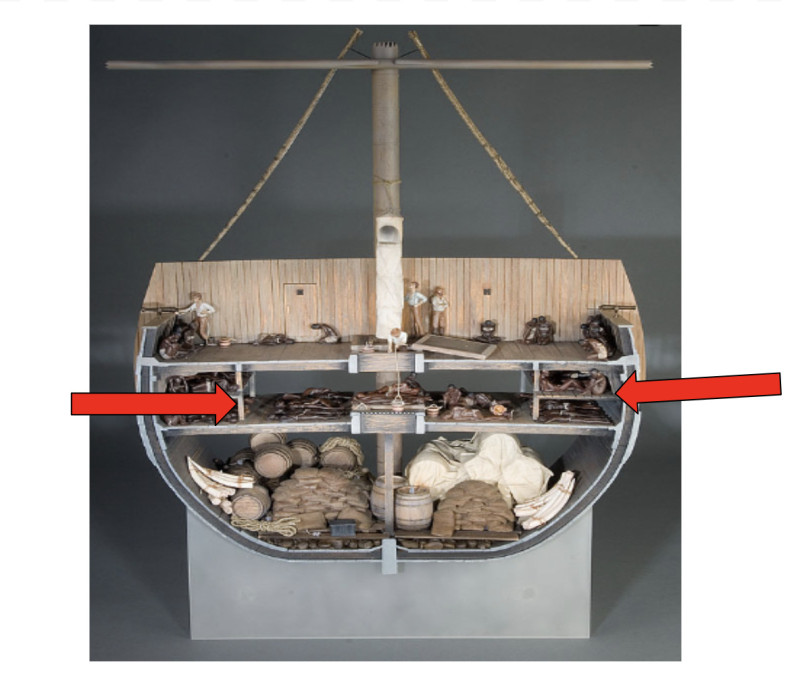

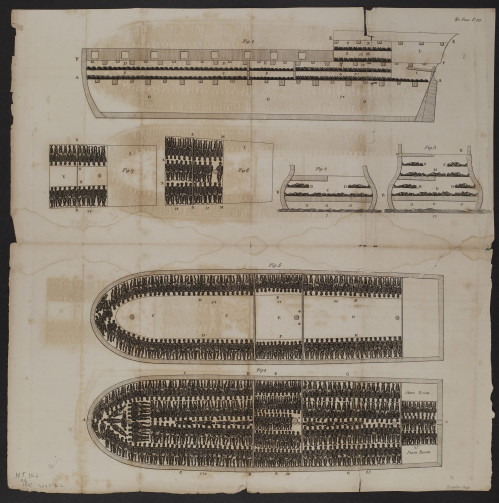

Although we tend to think of a physician as a person who takes an oath to “do no harm,” African Americans have not always been treated with care and respect by members of the medical community. Beginning in 1619 with the forced migration of enslaved Africans to British North America, Black people have historically endured numerous acts of violence and laws restricting their freedoms. The image below illustrates a commonly used packing method, one of the many inhumane conditions used by slave traders on the treacherous middle passage journey. Even those who were free could be kidnapped back into slavery, or otherwise legally assaulted. Enslaved people’s bodies were subject to painful and involuntary experimentation and medical and psychological experiments, in addition to being branded, whipped, and tortured routinely. The practices surrounding involuntary medical experimentation did not match the ideals of “freedom and “equality,” written into our Founding documents.

To learn more about the Middle Passage, explore this entry in Encyclopedia Virginia.

- Do you think slave traders and slave owners understood that people in bondage felt pain?

- Do you think the transatlantic crossing was humane?

- How do you think the kidnapped people’s health was monitored during their journey?

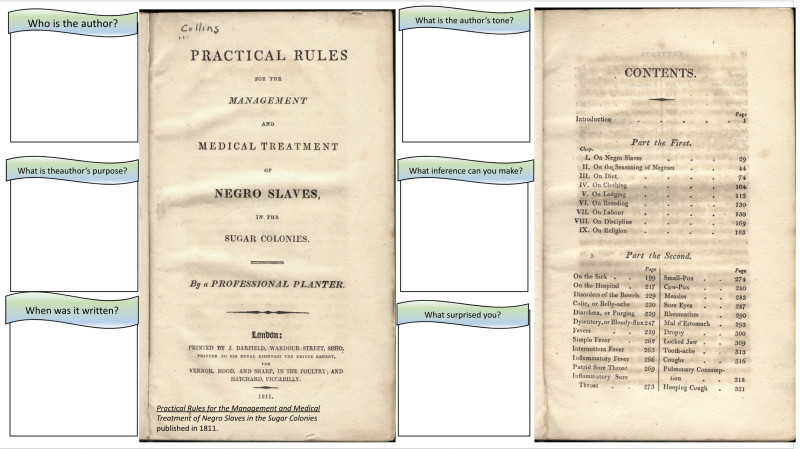

The methods for treating the subjugated population were developed by slave owners, not physicians. Defined as chattel, sick African Americans were largely cared for by the plantation mistress, planter, or other enslaved midwives and caregivers who provided care to the enslaved as needed.

Analyze the images on this Google slide two, reviewing this planter-created handbook for the care of the enslaved. Tap each Answer Me box to respond using the text boxes on your copy of the Google slides.

After you examine these pages from the handbook, turn and talk to a partner, or if you are working virtually, exchange messages on your Google slides perhaps using different colored text in the text boxes to compare your thoughts.

- Does a planter have the same knowledge of medicine as a doctor?

- How invested do you think the slave owners were in caring for their enslaved humans?

- What other topics are included other than guidance on how to treat specific medical conditions or ailments?

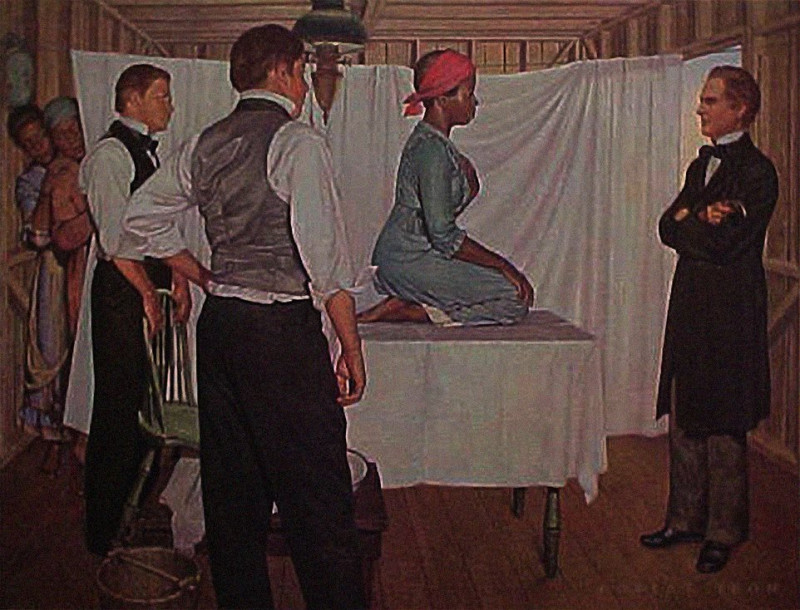

James Marion Sims was a physician in antebellum South Carolina, where white people were widely considered to be superior to other races. He maintained that his scientific efforts were for the greater good of other white citizens. Enslaved African Americans (and at least one white immigrant woman, Mary Smith) endured painful and risky experiments and surgeries by Sims. These procedures were performed on the enslaved under contracts between Sims and their enslavers, and according to Sims, the consent of the patients. Sims continues to be a subject of debate within the medical ethics community and historians. Some critics argue Sims was a “butcher” while others defend his medical practices, saying that he advanced the field of medicine and improved healthcare for all women. In 2018, a statue of James Marion Sims was removed from Central Park.

- Why do you think white Southerners permitted medical experimentation on enslaved people?

- What does the decision to remove the statue of Sims say about the way our thinking as a society is changing around the topic of monuments and memorialization in the public square?

The legacy and debate over Sims’ work and the treatment of patients of color within the medical profession persist today. A 2016 study revealed that some white medical professionals still believe there are biological differences between Black and white patients and their tolerance for pain.

This video from 2017 offers further context for persistent inequalities in medical care.

- In what ways are communities discussing and looking to correct medical disparities for women of color in more recent years?

- Do you think the early mistreatment contributes to African Americans’ mistrust of the medical community today?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

Are the rights of citizenship as defined by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution equally available to all people?

Before the Civil War, slaves received little to no medical care outside of their plantation community. The previous bonds of slavery eventually manifested into post-emancipation policies of segregation. Following the war, very few people of color were professionally trained as nurses, physicians, or surgeons. Although the 14th Amendment granted citizenship to the formerly enslaved, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was necessary to give them equal protection under the law.

Listen to this segment from the narrative podcast Seizing Freedom, “Dethroning Disease,” featuring Booker T. Washington’s 1914 address to the Tuskeegee Institute conference on “Fifty Years of Negro Health Improvement in Preparation for Efficiency.” Washington discusses how the federal government claimed that it wanted to address the disproportionate levels of health problems among African Americans. For African Americans in Alabama, this was a surprise, considering that from the end of Reconstruction into the Jim Crow era, people of color rarely received assistance from the federal government for anything.

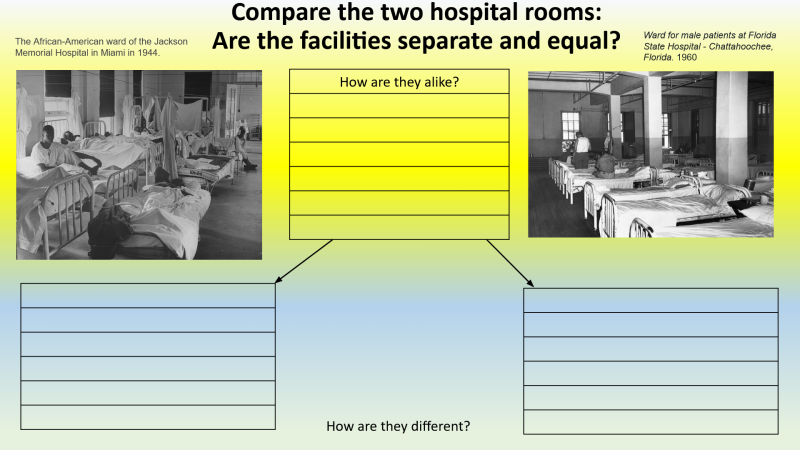

Jim Crow ordinances and state laws became common across the country; they were used to roll back the new freedoms gained by the 14th Amendment. African American citizens faced discrimination, racial terror, and white mob violence from groups including the Klu Klux Klan, and were forcibly removed from communities known as sundown towns. After the Civil War, medical school attendance became a reality for those African Americans wishing to become physicians or surgeons. Admission was limited to a few Black medical institutions; in 1868, Howard University College of Medicine opened in Washington, D.C., and in 1876, the Medical Department of Central Tennessee College (now Meharry Medical College) was founded in Nashville. The schools were established by white physicians and administrators and remained under their control. More Black colleges and universities began to be established to educate members of the African American community. However, the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling meant the medical professionals who taught and attended segregated medical schools remained more isolated within the medical community. The idea of “separate but equal” existed in many aspects of their lives, including schools, medical facilities, and healthcare. White Americans restricted most opportunities for social interaction, including medical treatment, under the doctrine of “Separate but Equal. Black doctors were often barred from joining chapters of local medical societies and the American Medical Association, leading to the formation of their own association for Black medical professionals, the National Medical Association.

Analyze and compare the images of two hospital rooms pictured on slide number three:

- Are the facilities separate and equal?

- Did the African American patients receive the same standard of care?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

Were medical ethics always applied to science and medical research in the treatment of people of color?

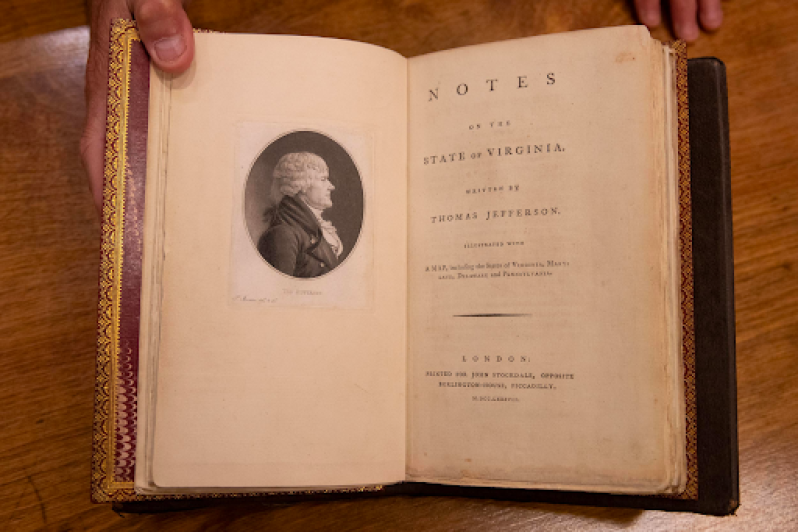

Eugenics was a system of beliefs and practices developed in the early 20th century that was based on the theory of white superiority. The objective was to increase the population of “desirable” groups and limit the ability of racial minorities and people with mental or physical disabilities to reproduce. During the early 1900s, eugenicists cited the influence of the earlier writings of President Thomas Jefferson. In “Notes on the State of Virginia,” he described his enslaved community at Monticello as “emitting a very strong and disagreeable odor; were in reason, much inferior; in imagination were dull, tasteless, and anomalous. ”

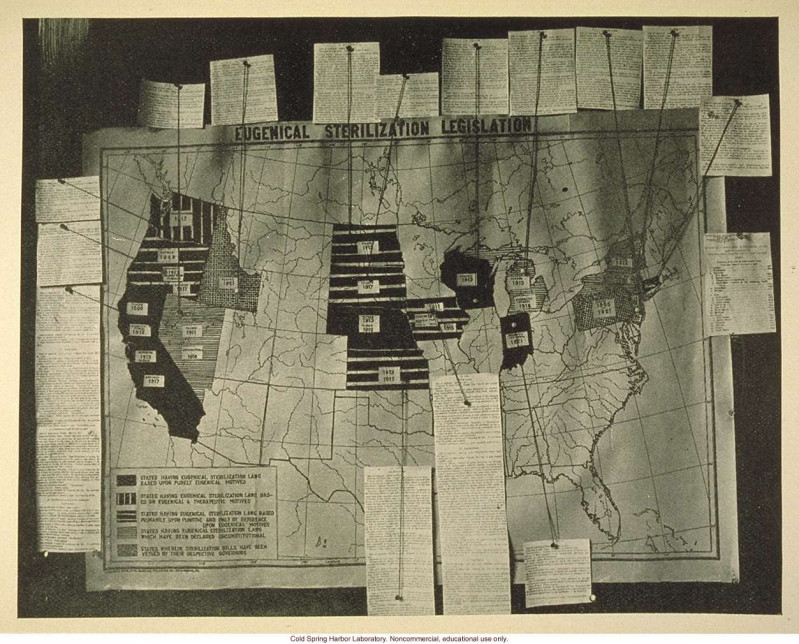

The University of Virginia, founded by Jefferson, was one of the foremost institutions practicing eugenics at the time. Prominent members of the university’s leadership and faculty perpetuated the ideas of white superiority and attempted to prove them through science. By the early 20th century, 32 states including Indiana, Connecticut, Washington, California, and Virginia passed sterilization laws, targeting people of color, and those with disabilities. In 1903, The American Breeders’ Association was the first “scientific” organization created to promote the science of eugenics.

In 1906, The University of Virginia's Anatomy Chair, Dr. Robert Bean, published a series of studies, arguing extensively that the physical features of African Americans were evidence of their inferiority. He insisted that this made them more susceptible to diseases and irregularities. Other faculty members supported Bean, advocating for political disenfranchisement and a segregated education system.

Kellogg’s cereal founder John Harvey Kellogg instigated a Race Betterment Foundation in 1914. The foundation promoted eugenics and racial hygiene (practiced in its most extreme forms by the Nazi eugenicists in Germany). He used the foundation to establish a “pedigree registry,” furthering the case for a “pure” white race by matching up healthy white couples without “disabilities” of any kind. Kellogg’s registry was based on selective breeding as used with animals and plants.

In 1924, the state of Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act. It was designed to prevent racial mixing. Examine the links provided and the image of the Virginia statute. Answer the questions using the text box(es) on slide four.

- How do you think the participation of the medical community in the eugenics movement influenced the way some African Americans did or did not trust doctors?

- Do you think the 1924 Racial Integrity Act was for the common good?

- What does the law’s title tell you about the law’s intent?

In addition to practicing the ideas of racial hygiene, eugenicists also advocated for forced sterilizations of “undesirable” people. During the 20th century, over 60,000 people in the United States were sterilized against their will. Between 1907 and 1937, 32 states passed sterilization laws, but the practice continued for decades. Over time, women, especially Black women, were sterilized at much higher rates than men.

This image shows a map, created around 1922 by the Eugenics Record Office at the Carnegie Institute of Washington, showing the states which had passed eugenic sterilization legislation. At the time sixteen states had passed or attempted to pass some kind of sterilization legislation.

- What do you notice?

- What patterns do you see on the map?

- What might explain the data you observed on the map?

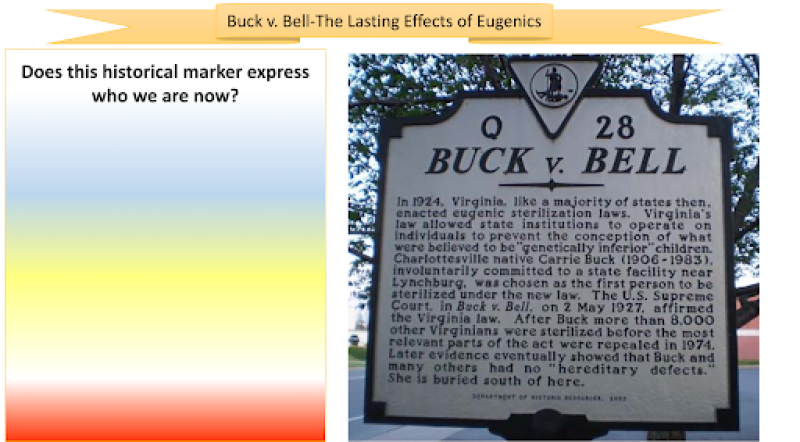

The 1924 landmark Buck v. Bell Supreme Court case upheld a Virginia statute that allowed eugenic sterilization of genetically unfit people. Carrie Buck, and her mother Emma, were committed to the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and the Feeble-Minded in Lynchburg, Virginia. Carrie and Emma were both judged to be "feebleminded" and promiscuous, primarily because they both had children out of wedlock. Carrie's child, Vivian, was judged "feebleminded" at seven months of age.

With an elbow partner, analyze and discuss the image of the historical marker using slide number five, then record your response in the text box.

- Does this historical marker express who we are now? (As a nation? As caregivers?)

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers as an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

Should Americans trust the federal government to make safe decisions about matters of public health?

Listen to a second segment from the narrative podcast Seizing Freedom, “Dethroning Disease.” In this segment, historian and host Kidada Williams discusses how Booker T. Washington promoted a Health Movement, instituting the first National Health Week, a 1915 campaign for African Americans to address the disproportionate levels of health problems within their own communities. Washington himself suffered from numerous medical health concerns and passed away shortly after getting the campaign off the ground. In 1921, Booker T. Washington’s successor at the Tuskegee Institute, Robert Moton, contacted the U.S. Surgeon General seeking his support for the Tuskegee Health Movement.

Turn to an elbow partner after listening to the segment, and consider these questions:

- How did enlisting the support of the Surgeon General change the campaign?

- In what ways did or didn’t the national attention help improve awareness of the medical disparities between white and Black communities?

- What was gained?

- What was lost?

The Health Movement continued until federal support ended and the program was shut down in 1951. While supporting the movement, government scientists simultaneously began conducting research on Black subjects without fully disclosing all of the facts about their study.

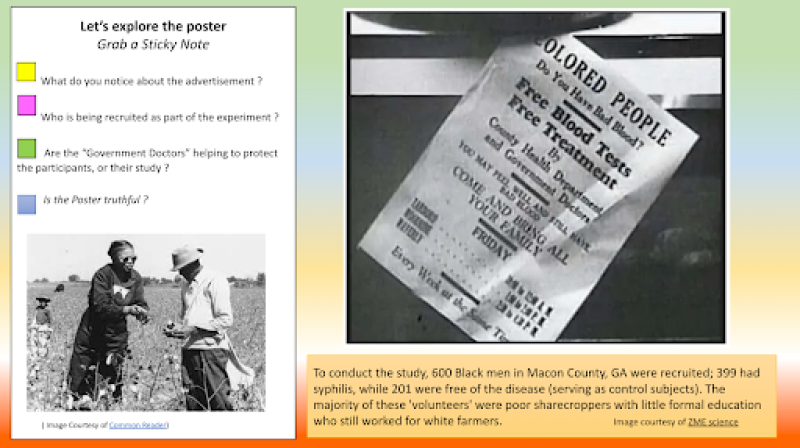

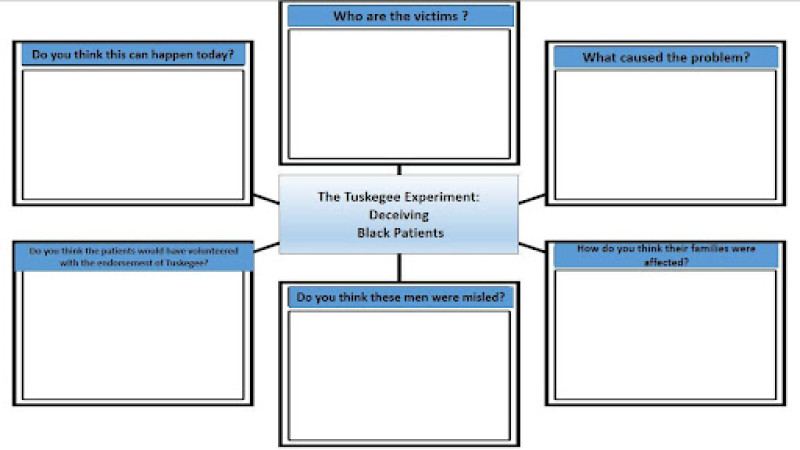

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male was a study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on a group of African American men with syphilis. Subjects were lied to about their current health status, and bribed with free meals, free medical exams, and burial insurance. The government exploited the minorities’ lack of access to medical care due to poverty, and their fears of various ailments to recruit and secure patient participation through the Tuskegee Institute, local community churches, and other black medical facilities. The subjects of the study were told they were being treated for bad blood, becoming patients who were unknowing participants in an extended observation of an untreated sexually transmitted disease, syphilis.

View this video describing the deceptive way the Tuskegee Study’s subjects were treated. When viewing the video, think about the following questions and complete the answers on slide number six, using the Soapstone graphic organizer activity. Tap the text box to answer the questions.

Fliers and posters were distributed in predominantly Black neighborhoods, and Eunice Rivers, a Black nurse, was hired to travel through the area to procure and retain patients. She was hired to track patient progress and administer medication and medical exams. Listen to this narrative segment of Seizing Freedom, “Dethroning Disease,” as one of the participants describes their experiences in the study and meeting Nurse Rivers.

The proctors of the experiment blocked any of the 399 infected participants from knowing they had syphilis, a disease treatable with penicillin. The disease was unknowingly transmitted to 40 of their wives, and 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis. Over 100 participants died from syphilis or related complications due to lack of treatment.

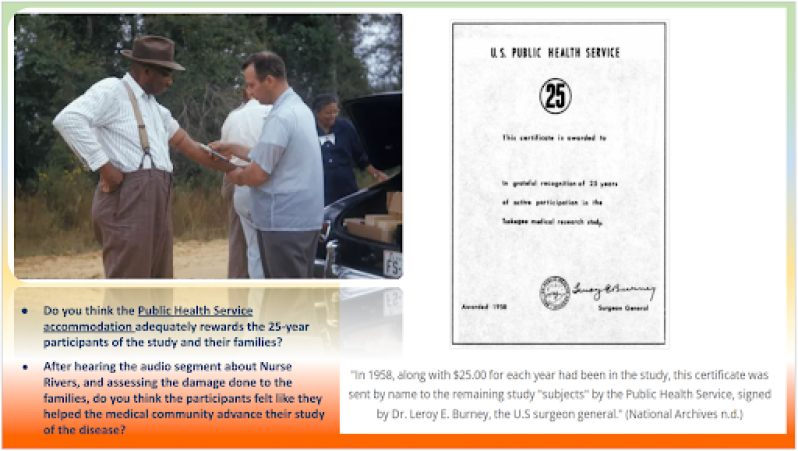

Participants were given an accommodation certificate and a monetary reward of 25 dollars for their participation in the study.

- Why do you think the participants did not question their treatment protocols?

- Do you think Nurse Rivers regretted her participation in the study?

Review slide number seven, and answer the questions using the text box.

Review slide number eight, and answer the questions.

- Do you think the Public Health Service accommodation adequately rewards the 25-year participants of the study and their families?

- After hearing the audio segment about Nurse Rivers, and assessing the damage done to the families, do you think the participants felt like they helped the medical community advance their study of the disease?

In 1997, President Clinton offered the survivors and their families an apology on behalf of the United States government. He acknowledged the profound immorality of the deception, as well as its legacy of everlasting mistrust.

Think about the Tuskegee experiment and the president’s apology. Reflect on your thoughts using the graphic organizer. Tap the text box to answer the questions on slide number nine.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

Can one person have a lasting effect on the world?

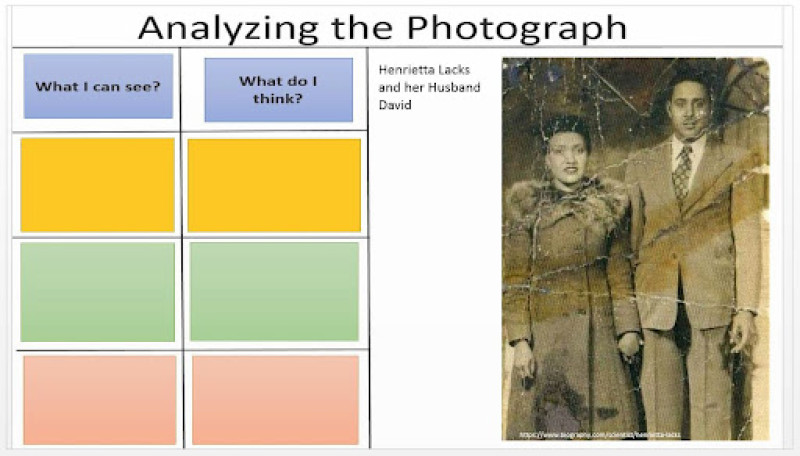

The Tuskegee experiment was shrouded in secrecy, and treating Black patients without informed consent did not end with that one study. In 1951, a young woman named Henrietta Lacks underwent cancer treatment at the famed John Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Henrietta was treated with radiation, and her doctor collected a sample of her cells. She later died on October 4, 1951, at the age of 31. She left behind a husband and five children. Review the link and the image on slide number ten, and answer the questions about Mrs. Lacks in your text boxes.

Dr. George Gey of John Hopkins University Hospital later made an important discovery about the cells of his patient, Henrietta Lacks. The laboratory found Lacks’ cells had a unique ability to renew themselves. John Hopkins Hospital made this discovery and did not disclose, compensate or seek the permission of Mrs. Lacks‘ family to use the cells in further research.

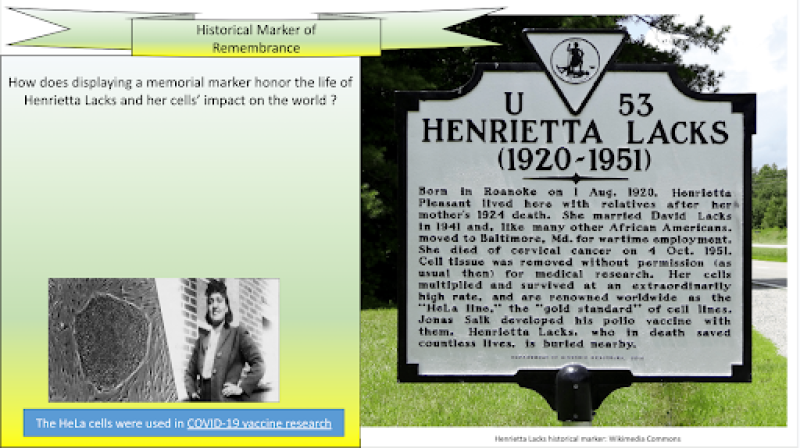

These “HeLa cells,” as they became scientifically referenced, became Mrs. Lacks’ contribution to science, and have since been requested by others conducting research, and used all over the world. Soon after the cell discovery, a vaccine for polio was produced from their use. The HeLa cells helped doctors in the United States eradicate polio within 60 years. Other discoveries related to the HeLa cells include research to map the human genome, and the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to fight against cancer. German virologist Harald zur Hausen won the 2008 Nobel Prize for his research contributing to a vaccine that helps prevent the strain of cancer that killed Henrietta Lacks, the Human Papillomavirus 18 (HPV-18). More recently, the HeLa cells were used to assist in the creation of the COVID-19 vaccine.

In subsequent years, the Lacks family protested the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine for the use of the cells without informing Mrs. Lacks or later obtaining her family’s consent. The school maintains that in sharing the cells, they have not profited from their use.

In 2010, a historical marker honoring Henrietta Lacks was placed by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources in Mrs. Lacks’ hometown of Halifax, Virginia. Review slide number eleven, and answer the question about the historical marker.

Do you think Henrietta Lacks deserves more recognition? Turn and talk to a partner or exchange messages in your text boxes.

- Should her family receive compensation from the medical community?

- Do you think her cells have made a significant difference in modern medicine?

- Do you think this revelation helped or hurt the relationship between the African American community and white doctors?

View this video from the American Medical Association featuring immunologist and COVID-19 vaccine pioneer Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett discussing her efforts to address socioeconomic and racial disparities in the field of global healthcare.

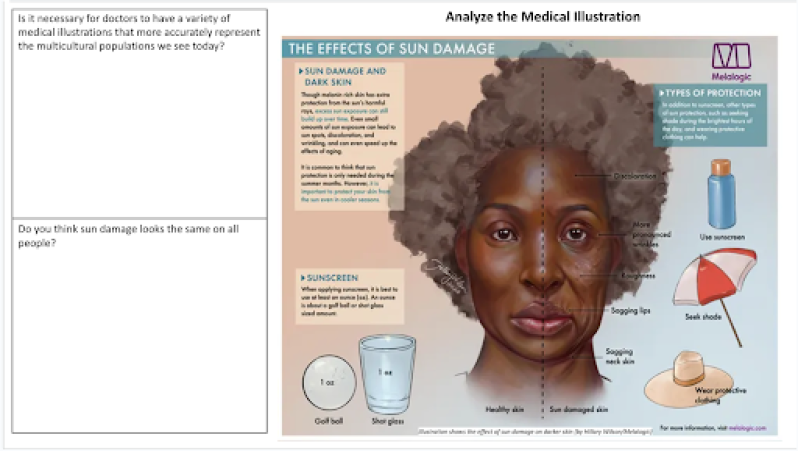

African Americans continue to be underrepresented in modern medical research science. In recent years, more research hospitals and medical schools are taking steps to increase minority participation. Another area of concern is a lack of resources for medical training that reflect a wide spectrum of patients and treatment. A 2018 study published by the National Institute of Health found less than 5% of images in four of the medicine textbooks assigned at top medical schools in the United States show dark skin.

African American medical illustrator Hillary Wilson and others in her field are trying to help change those statistics. Combining her talent for drawing with her medical knowledge, she created this image about the effects of sun damage. Analyze slide number twelve and answer the questions using the text boxes.

Do you think this type of inclusion might help to increase African Americans’ faith in the medical community?

- Did the image surprise you?

- How might more diverse representations in medical training materials improve the field of medicine as a whole?

- What actions might help improve African Americans’ trust in the medical profession?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

Alabama Backroads “The Tuskegee Study.” Accessed July 15, 2022.https://www.alabamabackroads.com/the-Tuskegee-Syphilis-Study.html.Black Past “John Henry Jordan (1870-1912).” Accessed August 13, 2022.https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/jordan-john-henry-1870-1912/.

Boyle, Patrick. “Clinical Trials Seek to Fix Their Lack of Racial Mix.” AAMC. Association of American Medical Colleges, August 20, 2021.https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/clinical-trials-seek-fix-their-lack-racial-mix.

"Buck v. Bell." Oyez. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/274us200.

Catte, Elizabeth. "Eugenic Sterilization in Virginia" Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, Accessed July 25, 2023. Last updated: September 06, 2023. Catte, Elizabeth. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/eugenic-sterilization-in-virginia/.

Center for Disease Control: National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Center for Disease Control and Prevention “US Public Health Service Syphilis at Tuskegee.” Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.Cooper Owens, Deirdre. “More than a Statue: Rethinking J. Marion Sims' Legacy.” Rewire News Group. Rewire News Group, February 21, 2019. https://rewirenewsgroup.com/2017/08/24/statue-rethinking-j-marion-sims-legacy/.

Highland, Michael, ed. “American Breeders Association · Controlling Heredity · Special Collections and Archives.” Special Collections and Libraries. University of Missouri, 2011. https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/controlling-heredity/mizzou/breeders.

Holland, Brynn. “The 'Father of Modern Gynecology' Performed Shocking Experiments on Enslaved Women.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, August 29, 2017. https://www.history.com/news/the-father-of-modern-gynecology-performed-shocking-experiments-on-slaves.

John Hopkins Medicine” The Legacy of Henrietta Lacks: The importance of the HeLa Cells.” Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henriettalacks/importance-of-hela-cells.html.

Louie, Patricia, and Rima Wilkes. “Representations of Race and Skin Tone in Medical Textbook Imagery.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institute of Health, April 2018. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29501717/.

National Archives “Memorandum Terminating the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.” Accessed July 15, 2022.https://catalog.archives.gov/OpaAPI/media/650716/content/arcmedia/fhh/6005_001_a.gif.

National Archives “Rediscovering Black History” Accessed July 15, 2022.https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2017/05/09/if-not-for-the-public-outcry-the-tuskegee-syphilis-project-study/.

NIH United States National Library of Medicine “Opening doors: Contemporary African American Academy Surgeons.” Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/aframsurgeons/history.html.

NYAM History of Public Health “All in the details.” Accessed August 19, 2022.https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/tag/hospital/.

Reynolds, Preston. "Eugenics at the University of Virginia" Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, Accessed 25 Jul. 2023. Web. 13 Sep. 2023.

Skloot, Rebecca. 2018. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. London, England: Picador.

Somashekhar, Sandhya. “The Disturbing Reason Some African American Patients May Be Undertreated for Pain.”

The Washington Post. WP Company, October 26, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/04/04/do-blacks-feel-less-pain-than-whites-their-doctors-may-think-so/?utm_term=.2840a1e527ab.STAT ”5 Important ways Henrietta Lacks changed medical science.” Accessed August 26, 2022.https://www.statnews.com/2017/04/14/henrietta-lacks-hela-cells-science/#:~:text=Scientists%20at%20the%20Tuskegee%20Institute,the%20countries%20of%20the%20world.

Stern , Alexandra Minna. “That Time the United States Sterilized 60,000 of Its Citizens.” HuffPost. HuffPost, January 8, 2016. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/sterilization-united-states_n_568f35f2e4b0c8beacf68713.

Sutori “The History of Henrietta Lacks.” Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.sutori.com/en/item/1947-50-henrietta-lacks-had-three-more-children-following-the-family-s-move-th.

The Atlantic “The struggle and triumph of America’s first black doctor.” Accessed August 20, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/12/black-doctors/510017/.

“The Syphilis Study at Tuskegee Timeline.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 5, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.“Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment: Short Documentary of Deadly Deception.” YouTube. Daily Dose Documentary, January 21, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4wFqyQxAPnM.

“Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust among Black Americans.” Commonwealth Fund. Commonwealth Fund, January 14, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans.

UVA Today “UVA and the History of race: Eugenics, the Racial Integrity Act, Health disparities.” Accessed July 15, 2022. https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-and-history-race-eugenics-racial-integrity-act-health-disparities.

Wall, L L. “The Medical Ethics of Dr. J Marion Sims: A Fresh Look at the Historical Record.” Journal of medical ethics. U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2563360/#:~:text=It%20is%20true%20that%20under,these%20slaves%20were%20unwilling%20patients.

Yancey-Bragg, N'dea. “Patients in Medical Illustrations Are Usually White. Meet the Black Artists Trying to Change That.” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, December 20, 2021. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/12/18/black-artist-brings-diversity-medical-textbook-illustrations/8892939002/.

ZME Science “Remembering the Tuskegee experiment: when rural Alabama Black men were intentionally exposed to syphilis with no treatment.” Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.zmescience.com/science/news-science/what-was-tuskegee-experiment-0423/