This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

A Grave Injustice

Read for Understanding

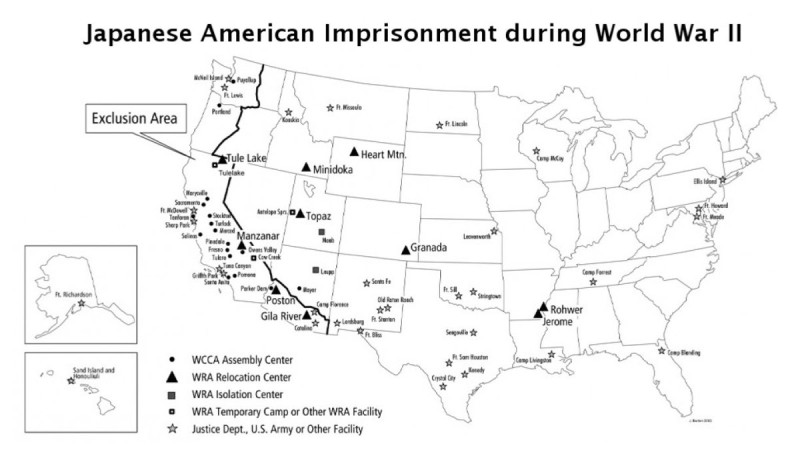

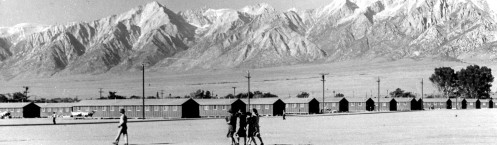

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. military and the FBI arrested more than 110,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry. Taken to desert camps and confined for months or years, many of these Americans lost their homes and businesses. In this episode of The Future of America's Past, Historian Ed Ayers visit the largest of these camps, now a National Park Service site — and meets those keeping the memory alive.

Key Vocabulary

Allyship - when a person in a position of privilege supports, shows up for, supports, or promotes the voices of, and works in solidarity with marginalized and oppressed groups

Ancestry - your family background, including people who came before you, your ethnic origin

Backstory - a story that tells the background that led up to a historical event, or the main plot of a book, story, or film

Barracks - temporary living quarters or housing built by the military

Discrimination - unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people or things, especially on the grounds of race, age, religious beliefs, gender, or sexual orientation.

Dismantled - taken apart, broken up into pieces, or destroyed

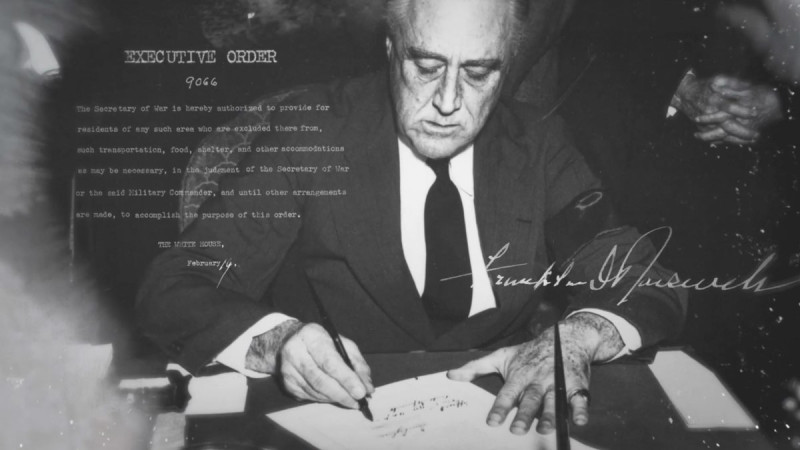

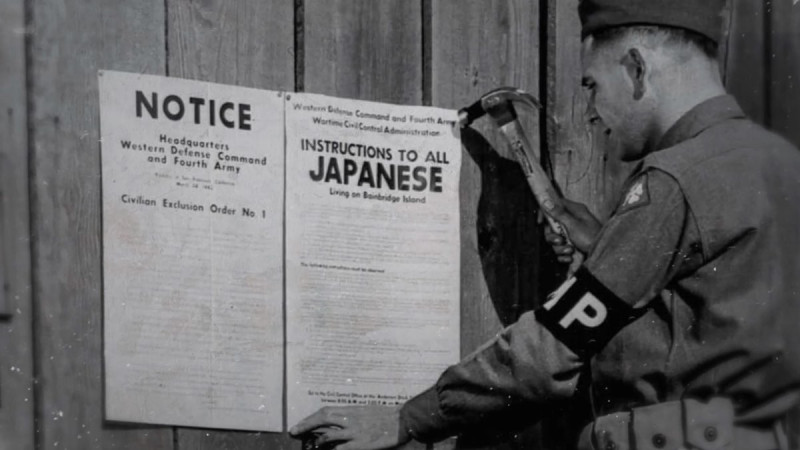

Exclusion Orders - An executive order signed by President Roosevelt in 1942 to allow the military to exclude (not include or allow) people from any location without a trial or hearing.

Executive Order - official statements issued by the President used to direct the Executive Branch of the U.S. Government

Hysteria - a situation in which individuals or groups of people behave or react in an extreme or uncontrolled way because of fear, anger, or other emotions.

Immigrants - a person who comes to live permanently in a foreign country

Incarceration - held in a jail, prison cell, or supervised military camp for political or legal reasons (to read about the use of “incarceration” & “internment,” visit Densho.org)

Internment - the forced relocation and incarceration in military camps, often for political reasons or suspected acts of terrorism

Latrine - a basic outdoor toilet or outhouse, shared in a camp or barracks.

Marginalized - to put or keep (someone) in a powerless or unimportant position within a society or group

Material culture - the physical objects people create and use in daily life (ex. artifacts, clothing, food, buildings, documents, tools, and technology)

Negation - to cause something to not be effective, to make negative (harmful, unwanted, bad)

Pilgrimage - a journey, often to a sacred or special place with religious or historical importance

Population Centers - a geographical point that describes a centerpoint (or middle point) of a region's population, as used in the U.S. Census

Public Square - a public gathering place within a community, a shared space for community meetings

Racism - when a group of people is treated unfairly because of their race/skin color

Redress - to correct something unfair or wrong

Reparations - money that a country or group that loses a war pays to those most harmed because of the damage, injury, deaths, etc. that were caused

Resilience - the ability to become strong, healthy, or successful again after something bad happens

Rickety - poorly made and likely to collapse

Sanctuary City - limited cooperation by local governments in enforcing federal immigration laws or policies deemed unjust by the community

Sequestered - to remove or separate people or objects from others

Surreptitiously - done in secret, avoiding attention or notice

Systemic Racism - a form of racism embedded as normal practice in society, rooted in policy and law

Xenophobia - an extreme dislike or prejudice against people from other countries

Engage:

Does the legacy of Japanese incarceration teach us our Constitution is fragile when we allow hate and fear to reinforce xenophobia?

In recent years, social justice movements led by Millennials and Gen Z activists have used the power of social media and grassroots activism to support anti-racist educational, immigration, and government policy reforms. The role of young people in leading civil rights movements in the United States and abroad is not new, and we have much to learn from history and previous generations when we examine how our Constitutional freedoms have been defined, preserved, and challenged. In this Learning Resource, we will examine the effects of xenophobia on Asian Americans during World War II. In this video, historian Ed Ayers visited Manzanar, one of several former Japanese Incarceration Camps. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “When Hate and Fear Take Control.”)

Use the video, the vocabulary list provided in this Learning Resource, a dictionary, or thesaurus to complete the first Sketch and Tell activity using the Google Slides template provided. Your teacher may allow you to work in pairs or small groups to share your sketches, or if working remotely, use an online dictionary and collaborate via video conferencing in breakout rooms.

What symbols, shapes, and other visuals did you use on your Sketch to illustrate your understanding of xenophobia?

- How did the first video influence your sketch, definition, examples, and non-examples?

- How did these compare to the sketches, definitions, examples, and non-examples shared by your classmates?

In this next video, you will learn more about Manzanar and Japanese incarceration during World War II. Think about your previous understanding of what it means to be an American, or to have Constitutional rights. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “How Japanese American Incarceration Began.”)

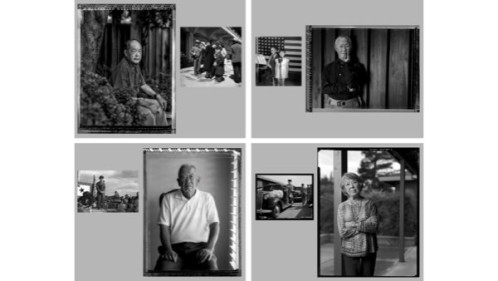

Take a few minutes to explore these images from the video and a map of the locations where Manzanar and other Japanese Incarceration Camps were located. As you view each image, revisit these earlier topics:

- What does it mean to be an American?

- What does it mean to have Constitutional rights?

Select one of the images from the photo gallery and complete the second Sketch and Tell activity provided in the slide deck, illustrating your thoughts on the incarceration of Japanese Americans at Manzanar during World War II. Your teacher may allow you to work in pairs or small groups to share your sketches, or if working remotely, use an online dictionary and collaborate via video conferencing in breakout rooms.

When you have completed your Sketch and Tell, you may revisit your earlier slides and update your vocabulary definitions or examples and non-examples, based on the new information you have learned from the second video and your exploration of the images. Your teacher may provide an opportunity for you to share your work with your classmates via a Gallery Walk, either in person or via collaborative slides if working remotely.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

In what ways were the lives of Japanese American families incarcerated at camps affected by Executive Order 9066?

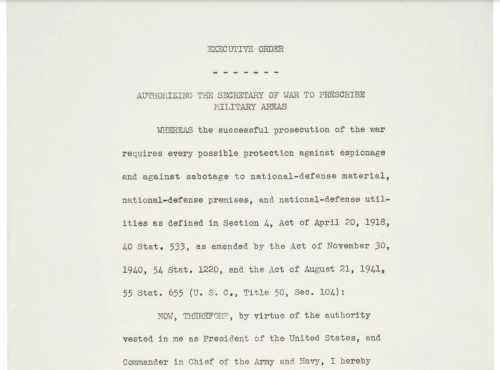

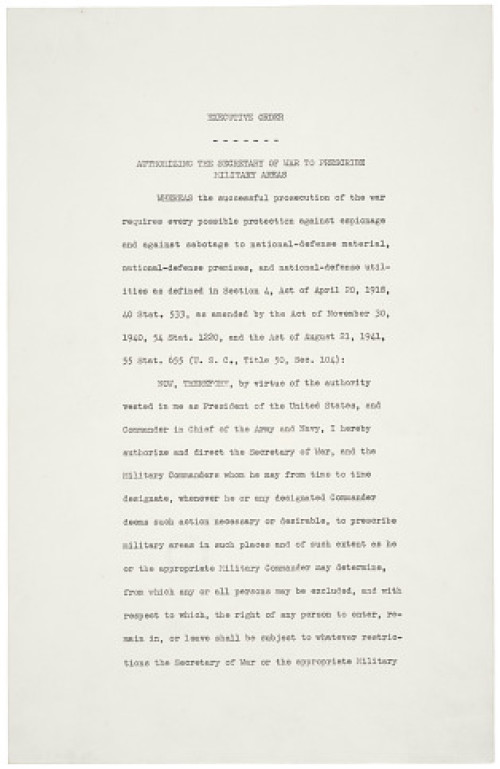

The children of Manzanar were particularly vulnerable as their families, education, and childhoods were interrupted by war and Executive Order 9066. Take a few minutes to examine the text of this federal document. You may click on the images for each of the pages, or you may choose to cut and paste the transcript into the Rewordify app to help simplify the text.

- What do you notice?

- Which federal agencies or authorities were responsible for Executive Order 9066?

- What did the order specifically authorize or require?

- What questions do you still have about Executive Order 9066? Additional information may be found here.

As families were relocated to Manzanar, the youngest Japanese Americans were left with more questions than answers. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “Remembering Incarceration at Manzanar.”)

Turn and talk to an elbow partner, or if working remotely, your teacher may provide access via video conferencing in a breakout room or a collaborative tool such as Google Docs or Google Slides.

- How did Mary and her siblings survive/show resilience after the loss of their parents?

- What misunderstandings did Mary have when she was first made aware of the orders for her family to move to a camp?

- How did she come to understand a new meaning of the word camp?

- Describe the living conditions for families at camps like Manzanar.

- What sacrifices did Mary and her siblings make while incarcerated at Manzanar?

- Compare and contrast Mary’s coping skills with those of others incarcerated at Manzanar. How did other Japanese Americans cope with being sent to the camp?

Think about the texts you read for Executive Order 9066 and the effect it had on families like Mary’s. Spend a few minutes recording your thoughts in a Reflective Journal entry.

Your teacher may ask you to record your Reflective Journal as an exit ticket.

Explain:

What material culture can we examine to get a better understanding of the harsh conditions Japanese Americans were forced to endure in incarceration camps during World War II?

Manzanar was not the only Japanese incarceration camp built in response to Executive Order 9066. There were ten camps built, with numerous Temporary Relocation Centers established as Japanese American families were chaotically transitioned from their homes towards the camps. Much of what we know about this process and life in the camps was hidden at the time when it was occurring. Photojournalists who tried to document these experiences were often silenced by the government, which attempted to downplay the xenophobia and mistreatment of these American citizens during wartime. Historian Ed Ayers visited the Japanese American National Museum for a closer look at the way photography has preserved the history of Japanese incarceration during World War II. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “Picturing the History of Incarceration.”)

The work of photojournalists like Dorthea Lange and Ansel Adams and the compelling images by incarcerated Japanese photographer Toyo Miyatake provide us with a better understanding of the daily sacrifices and hardships faced by Americans incarcerated at the camps. For many, their stories were not previously shared in textbooks or museums for many decades following the war. Projects like Paul Kitagaki’s exhibit, Gambatte! brings these images, documents, and stories out into the public square, where students and families can begin to understand the lasting legacy, and resilient spirit of the people directly effected most by this unconstitutional incarceration of American citizens. Spend a few minutes exploring the virtual exhibit, including the paired portraits you viewed in the video.

- Notice the images of veterans featured in the videos. How do these images change or add to your thoughts on how we honor and celebrate veterans?

- Which image or images of children at Manzanar were most compelling to you? Why?

- How did the paired portraits project change your thinking about Manzanar?

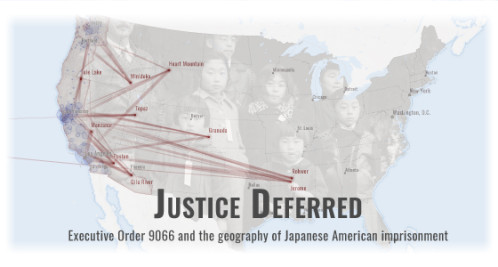

This ESRI StoryMap includes additional images from Lange, Adams, and Miyatake, providing both historical and geographical context to the story of Japanese American incarceration. Take some time to review the maps, images, and primary source documents embedded in the text. Use the menu bar located in the upper right corner of the StoryMap to navigate to each section. Use the scroll bar on the right side of the screen to move slowly through each section of the map. This will allow you to view animations and reveal new information.

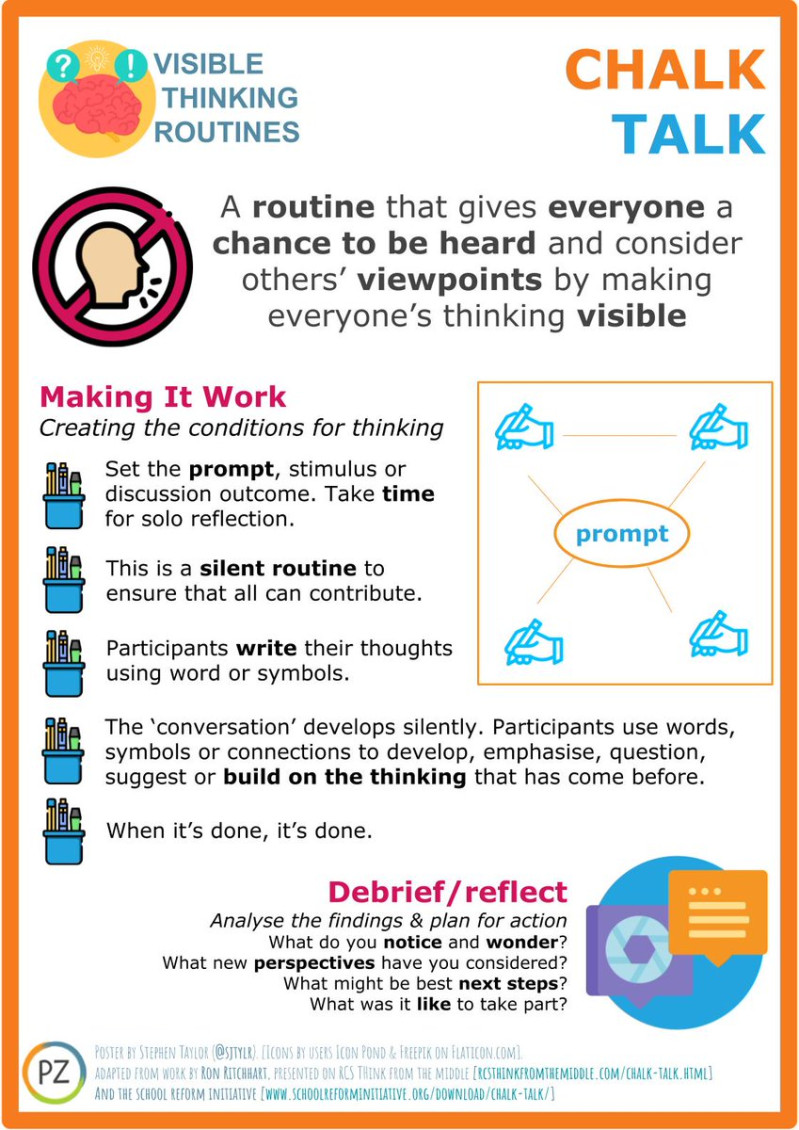

Once everyone in your class has had a chance to explore the “Justice Deferred” StoryMap, your teacher will provide a series of Chalk Talks for you and your classmates to respond to. They may also use a Google Slide tool for discussion. You should attempt to comment on at least three of the following topics:

The Prelude:

- What evidence of xenophobia is indicated in this section of the StoryMap?

- Using the maps, where are most first-generation Asian immigrants living in the pre-WWII United States? Where are there few or none?

- Compare and contrast the shared experiences of the second and third generation of Japanese immigrants to those of the first-generation immigrants.

The Order:

- What new information about Executive Order 9066 did you learn from the text and images as presented in this StoryMap? Did they change your thinking about the Order?

- Using the maps, what geographic patterns do you notice about the way Japanese Americans were moved within the military exclusion zones from the assembly centers to relocation centers to camps per the President’s Exclusion Orders?

The Relocation:

- Examine the material culture presented in this section of the StoryMap. How do the photographs, signs, and maps tell the story of families and communities whose civil rights were violated and lives disrupted as they made their way involuntarily to the camps? How do the animated maps/visualizations add to your understanding of this story?

The Camps:

- Using the images, text, and maps, how would you describe life in the camps for Japanese American families incarcerated at Manzanar?

The Resettlement:

- Use the graph, maps, and images to describe patterns you see in the way Japanese Americans were resettled after the closing of the camps. What evidence supports your thinking?

The Legacy:

- What evidence remains on the physical and cultural landscapes to remind us of this time in our history when xenophobia led to the loss of freedom and justice for so many Japanese Americans during World War II?

- What legislative and judicial actions have occurred over time to acknowledge and honor the sacrifices and resilience of those affected by Japanese American incarceration?

Your teacher may ask you to record your Chalk Talk answers as an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

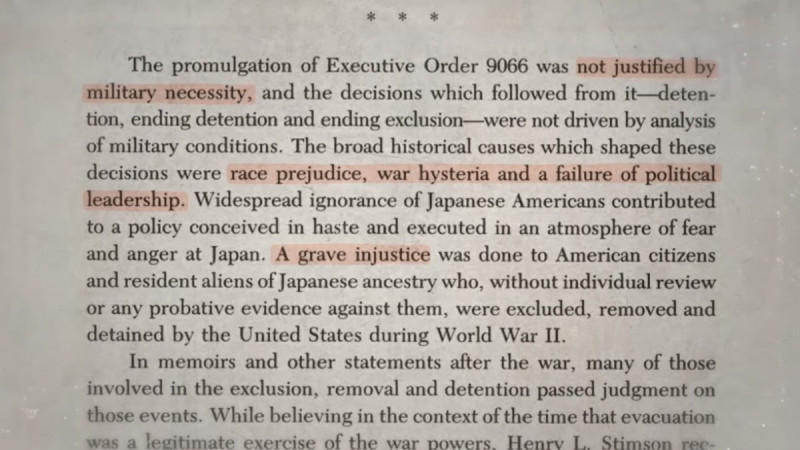

Are redress and reparations enough to compensate those whose lives are affected by prejudice, failed leadership, and A Grave Injustice?

In history, we learn how our thinking about people and events changes over time, and how sometimes the actions or decisions made by those in power, those who are entrusted as leaders, and even people in our communities or our own ancestors seem incredulous to us when we look at them through a modern lens. During the late 1960s, at the height of the Civil Rights movement, a group of Japanese American students explored their own history at the abandoned site of the former Manzanar incarceration camp, learning firsthand about xenophobia and racism. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “One Family's Legacy of Incarceration and Activism.”)

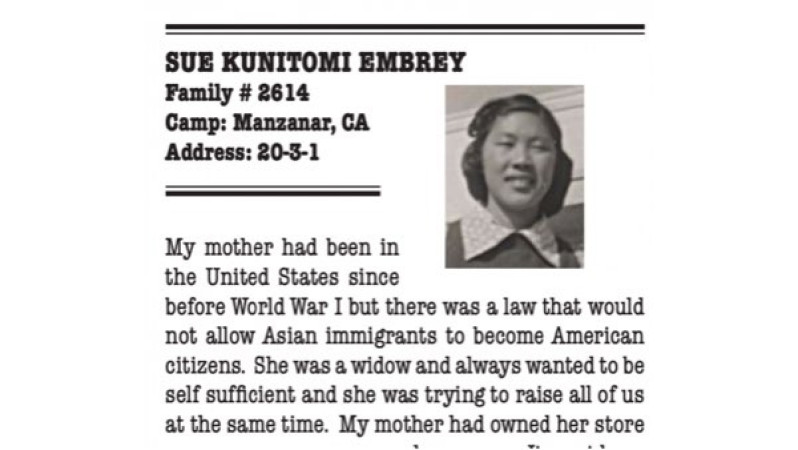

As Sue Embry and others turned the annual student pilgrimage to Manzanar into a student coalition to preserve and tell the true history of Japanese incarceration at Manzanar, not all of who were survivors of the camps were in agreement with these actions. Embry’s son, Bruce, recalls his mother’s words:

“Manzanar was the ultimate negation of democracy, but it can be more.”

Embry’s dream of preserving the history of all peoples who inhabited the Owens Valley, and creating a space for people to visit as a site of remembrance and reflection was finally realized in 1992. Take a few minutes to explore her brief biography and other resources on the Manzanar Historic Site webpage. Explore other biographies of those incarcerated at Manzanar from these ID Booklets developed by the National Park Service.

Be sure to examine the History and Culture sections of the site, as well as the Virtual Museum in the Collections section. Select at least one piece of material culture from the Virtual Museum to examine in more detail.

- How does this object reflect the history of this sacred space?

- Whose story does this object help tell?

- What can we learn about the past from this object?

- How does this object relate to the quote from Sue Embry?

Turn and talk to a partner about the objects you both examined, or if working remotely, your teacher may allow you to share via videoconferencing, breakout rooms, or a collaborative document.

Sue Embry and her classmates were not the only ones who became activists in support of telling the truth about the people whose lives were profoundly affected by the government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans at camps like Manzanar. Some activists, like Kathy Masaoka, turned their attention to demanding redress and reparations. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “Fighting for Redress and Reparations.”)

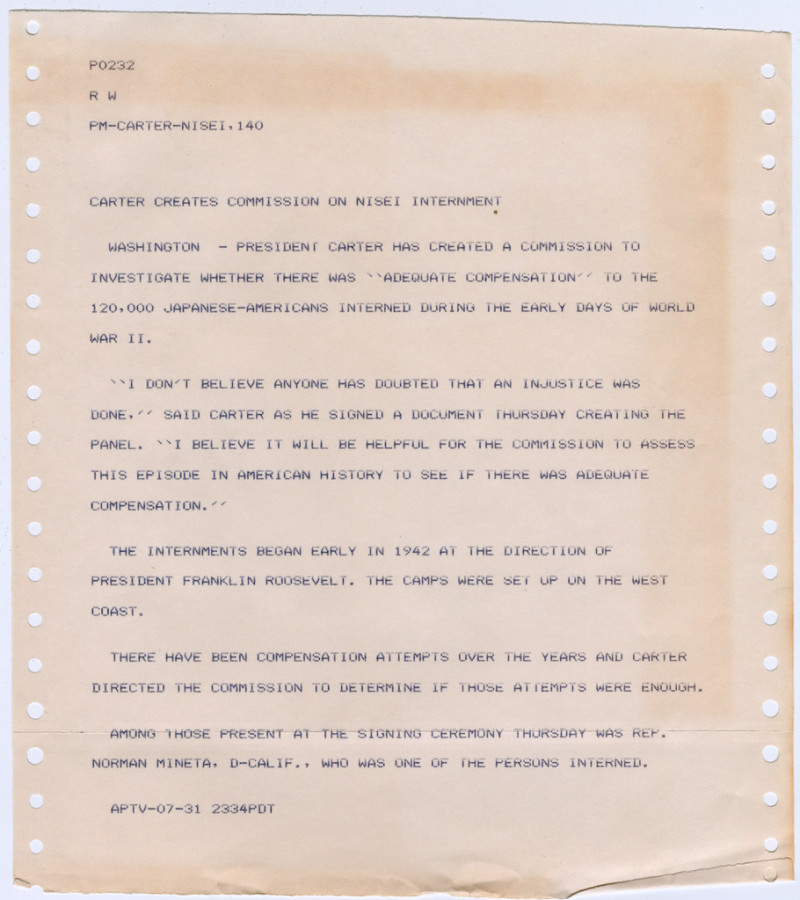

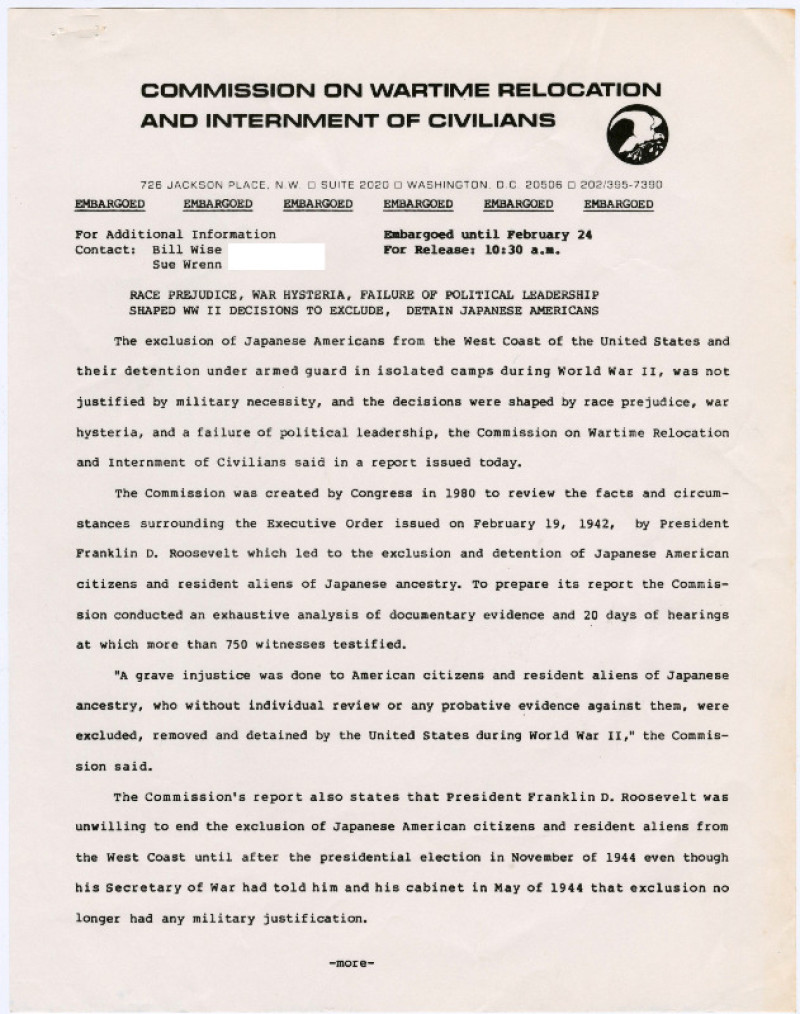

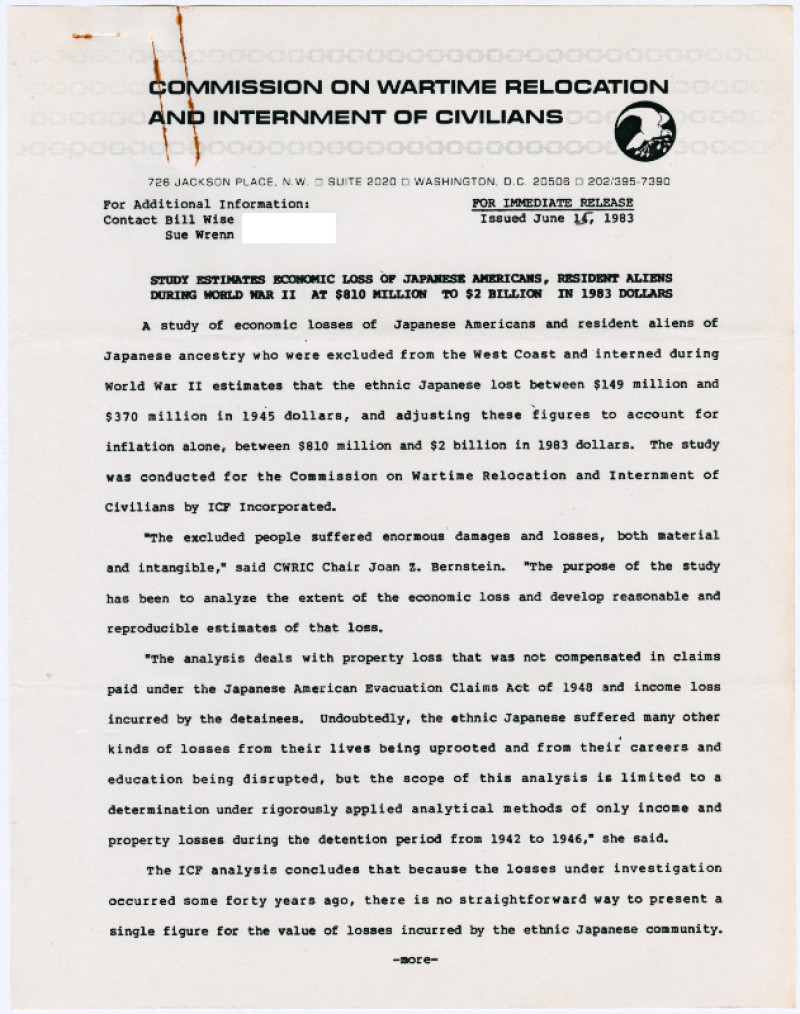

Take a few minutes to examine these documents from the 1981 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, a series of Congressional hearings ordered by President Jimmy Carter to examine the effects of Executive Order 9066 on Japanese Americans, the directives of the United States military forces requiring the relocation, and to make recommendations for “remedies.”

Now take a few minutes to explore connections between the video, the documents, and other resources using Bunk. If this is your first time exploring Bunk, select the “How Connections Work” icon located below the cards on the right side of the screen to discover how each tag and icon work.

- What new connections to the history of Japanese incarceration did you find most surprising to the content you learned from the video? Share a link to one of these connections you found most interesting (see the “Share connections” button at the bottom of the Bunk screen.)

- What other examples of injustices did you connect to the history of Japanese incarceration?

- Did you find mention or new understandings to any of these or other related documents as you explored Bunk?

- What new tag might you add to one of these Bunk connections?

- Explain why you added this tag, as it relates to one or more connections you made using Bunk.

We would love to hear more about your thinking around the connections you explored and the new tags you created using Bunk. If your teacher or a trusted adult permits, you may email us at editor@newamericanhistory.org or share via social media (links on our pages). Be sure to tag us as you share! You may also share your connections with your classmates as directed by your teachers, using a collaborative doc or other school-approved technologies.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

In what ways have younger generations of Japanese Americans leveraged the legacy of Manzanar to remind us of what goes wrong when innocent people in marginalized communities within a democracy are denied their basic rights?

It is not hard for Asian American students today to imagine the trauma their ancestors endured during the time of Japanese incarceration. In recent years, immigration policies such as family separation, disputes over sanctuary cities, and a polarized political climate with discussions of building border walls have resulted in a surge in xenophobia. The COVID-19 pandemic amplified these attacks, as all Americans witnessed increased acts of violence directed towards Asian Americans as the pandemic surged. Activists and artists like Traci Kato-Kiriyama are using art to ensure the next generation remembers the consequences of hate and racial violence. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “Putting Memories of Injustice and Resistance On-Stage.”)

- How does playwright Traci Kat-Kiriyama use her art to express her emotions as she thinks about her family’s history of incarceration at Manzanar?

- What lessons does she hope her audiences will learn from her work?

- How does the annual pilgrimage to Manzanar also speak to other marginalized groups who are persecuted today?

Complete the following statement: “I used to think …. Now I think….” based on what you learned from the video.

“There's this plot of land like 100 yards in back of the cemetery at Manzanar. They used to have this one area where there was this huge pond of broken dishes. So after they closed the camps the mess halls dumped all of these dishes and they got uncovered over time and it was sort of our ritual to go and pay our respects at the cemetery and then walk back to that pond of dishes.”

Examine this image of the broken dishes Kato-Kiriyama described, remnants of daily life for her family and other Asian Americans incarcerated at camps like Manzanar during World War II.

- How does Traci describe the dishes in the video?

- Why does visiting this “pond of dishes” seem to have importance to Traci?

- How does this annual pilgrimage build empathy and understanding toward Asian Americans and other marginalized groups?

Take a few minutes to explore this Bunk Connection.

- What evidence of xenophobia have you seen and heard in your own school or community directed towards Asian Americans or other marginalized groups?

- How have you and others helped show allyship towards neighbors or classmates experiencing hate speech or racism?

At the end of the video, Traci and others gathered at the annual pilgrimage make a declaration:

“What happened here shall never happen again.”

Rep. Grace Meng introduced a Resolution in Congress in 2021 to address the rise in anti-Asian violence and xenophobia. Read or listen to the text of the Resolution.

- Would you vote to support this resolution if you were a member of Congress?

- What steps might you and your school or community take next?

We’d love to hear your thoughts and ideas! If your teacher or a trusted adult gives you permission, you may reach out to us via social media (links on our pages) or email us at editor@newamericanhistory.org.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

Chinn, Paul. Dishes dumped at Manzanar: Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection. Los Angeles Public Library/Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection, 1988. https://tessa.lapl.org/cdm/fullbrowser/collection/photos/id/18013/rv/singleitem.

Jon Corippo, and Marlena Hebern. “EduProtocols - Sketch and Tell,” 2021. https://www.eduprotocols.com/sketch-and-tell/freetemplates.

“Document for February 19th, 1942: Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese.” National Archives and Records Administration. General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives and Records Administration, 1994. https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/?dod-date=219.

ESRI StoryMaps Team. “Justice Deferred.” ArcGIS StoryMaps. ESRI, December 9, 2018. https://storymaps.esri.com/stories/2017/japanese-internment/index.html.

Kitagaki, Paul Kitagaki. “Gambatte! Legacy of an Enduring Spirit, Triumphing over Adversity: JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION REFLECTIONS, THEN AND NOW .” Paul Kitagaki Jr. Paul Kitagaki Jr. Website, 2017. https://www.kitagakiphoto.com/exhibit.

Meng, Rep. Grace. “#StopAsianHate #BlackLivesMatter .” Twitter, March 27, 2021. https://twitter.com/Grace4NY/status/1375875521414848525.

National Park Service. “Map of World War II Japanese American Internment Camps.” Wikimedia Commons. National Park Service in the Public Domain, April 27, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_World_War_II_Japanese_American_internment_camps.png.

Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (2012). Reflective journals and learning logs. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Retrieved from https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide.

“Project Zero's Thinking Routine Toolbox.” PZ's Thinking Routines Toolbox | Project Zero. Harvard Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, 2016. http://www.pz.harvard.edu/thinking-routines.

Suárez-Orozco, Carola. “Addressing Xenophobia with Culturally Responsive Schools.” Share My Lesson. American Federation of Teachers, February 21, 2020. https://sharemylesson.com/blog/addressing-xenophobia-schools.

"The Future Of America's Past: A Grave Injustice." 2020. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com.

Watch, Human Rights. “Covid-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide.” Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch, October 28, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide.

University of Texas Libraries Diversity Action Committee. University of Texas, August 2015. https://sites.utexas.edu/utldiversityactioncommittee/lgbtqa-vocabulary/.

Xenophobia. University of Texas Libraries Diversity Action Committee. University of Texas, August 2015. https://sites.utexas.edu/utldiversityactioncommittee/lgbtqa-vocabulary/.