This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

A Public Calamity

Read for Understanding:

The pandemic now known as “COVID-19” was not the first public health scare. Almost exactly one hundred years before the recent global crisis the flu pandemic of 1918 affected most of the world. Like today, responses were mixed while many thousands died. How did citizens and officials respond, and how does it compare with our experience of COVID-19?

These Learning Resources may be adapted by your teacher and used in whole or in part, for large group or individual learning situations. Some activities are designed to include working with partners, or participating in a group discussion. For remote learning, your teacher may adapt these directions based on your school's policies and access to technology.

Key Vocabulary

Calamity - an event that causes great harm and suffering

Cartographer - a mapmaker, one who draws or designs maps by hand or using digital tools

Demographic - the study of human population using data such as age, race, gender, income, education, religion, occupation and other categories.

Infographic- a visual image such as a chart or diagram used to represent information or data

Influenza - commonly known as the flu, an illness that is caused by a virus and often has symptoms of fever, weakness, severe aches and pains, and breathing problems

Memorial - a monument, plaque, or ceremony that honors a person who has died or serves as a reminder of an event in which many people died

Obituary - an article in a newspaper about the life of someone who has died recently

Pandemic - an outbreak of a disease or virus which spreads very quickly and affects a large number of people over a wide area or globally

Public Health - the science of protecting and improving the health of communities through education, policy-making, and research for disease and injury prevention.

Quarantine - a strictly enforced isolation to stop the spread of disease (Note: self-quarantine is voluntary and involves avoiding contact for a period of time to help stop the spread of disease. For example, first responders may self-quarantine from their families because they are at higher risk of contracting illness due to their work.)

Segregated - race- or religion-based separation in public spaces including schools, public transportation, restroom facilities, and neighborhoods

Segregationist - a person who supports racial or religious segregation

Social distancing - a set of actions to limit face-to-face contact to stop or slow the spread of a highly contagious disease among people in a community

Structural racism - laws and public policies that create a disadvantage for people of color, including unfair employment, educational, housing, banking, and lending practices.

Engage: What can citizens and policymakers learn by studying how Americans historically responded to a public health crisis?

In the spring of 2020, communities across the United States were caught off guard by the sudden outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. There had been other epidemics in recent years, most far away and few reaching a level of concern that many Americans noticed. This virus was different—it was now in America, first in Washington state, and soon after in every state. Large events were canceled, schools were closed, nursing homes and hospitals were suddenly overwhelmed. In the span of a few weeks, life as we knew it changed. For many of us, this was our first experience with a public health crisis, and we had to learn and practice new terms such as “social distancing” and “self-quarantine.” But this was not the first time our nation had experienced great sickness and loss, and if history teaches us anything, it won’t be the last. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “A Public Calamity: A Ghost Town.”)

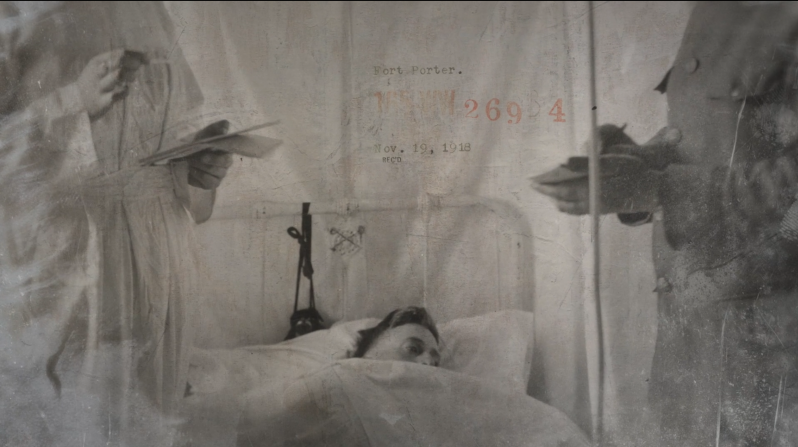

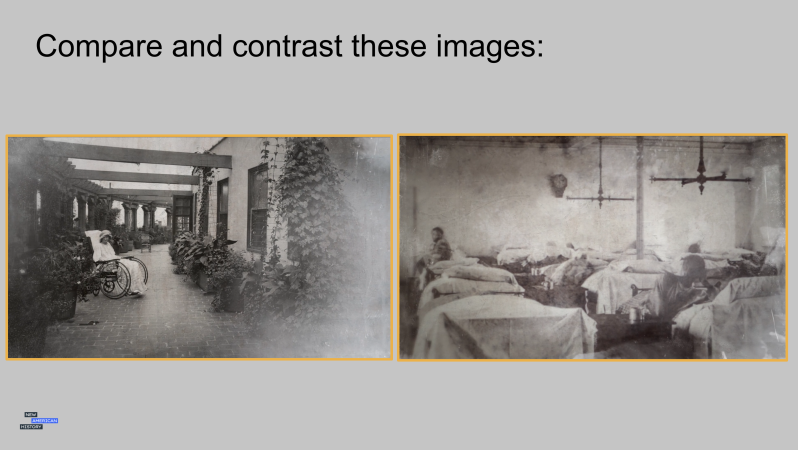

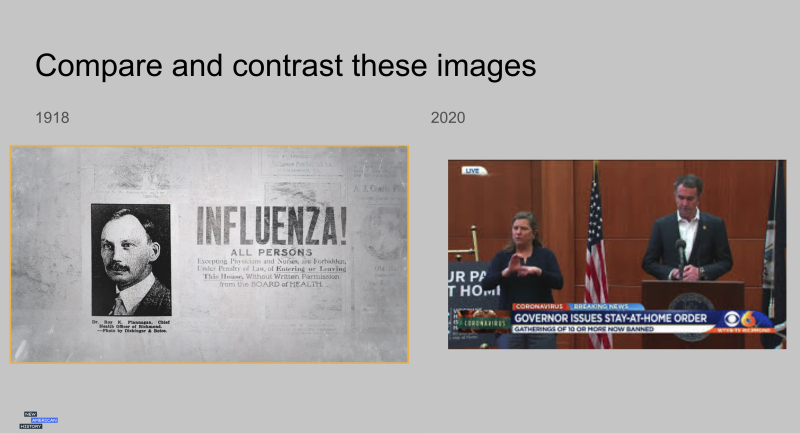

This film focuses on one town’s story, but Richmond, Virginia’s experience is a cautionary tale for many towns and communities. Our narrator, historian Ed Ayers, describes the 1918 flu pandemic while the viewer sees images from both the past and present pandemics. Take a few minutes to view some images from the video, and take note of any similarities and differences you observe. Your teacher may have you view these online, or may share them via Google Slides with you and your classmates. You may turn and talk to a family member or classmate if viewing online via videoconferencing or television.

- What do you notice about these images?

- Which image from the 1918 pandemic caught your attention? Why?

- What captions might you give each of the images?

- Which of the images from 2020 are most similar to the images taken in 1918?

- How did the early public awareness of the 1918 and 2020 pandemics seem similar?

- How were they different?

The first segment of this episode of The Future of America’s Past notes that in 1918, “the economy was strong, unemployment was low,” and, despite the flu, “politicians called for a return to normal life.”

- How do these descriptions of 1918 compare to the economy and society in 2020?

- Can you cite specific examples of recent economic or political statements that you have seen or heard on the news that are similar to those from 1918?

- Which of these statements about the 1918 pandemic from the video might also describe a news report or image you may see on television from 2020?

- Doctors begged for mercy.

- Politicians called for a return to normal life.

- The flu made Richmond, Virginia, a ghost town. In a scene that played out across the country, streets were deserted.

- City officials closed schools.

- They told residents to wash their hands, wear gauze masks, keep their distance.

- They put medical students to work.

- They had seen the flu in the past. Every year, it killed some of the very young and very old, spreading, but rarely out of control. This time, it did something new.

- It sickened and felled women and men in their 20s and 30s.

- It made children orphans

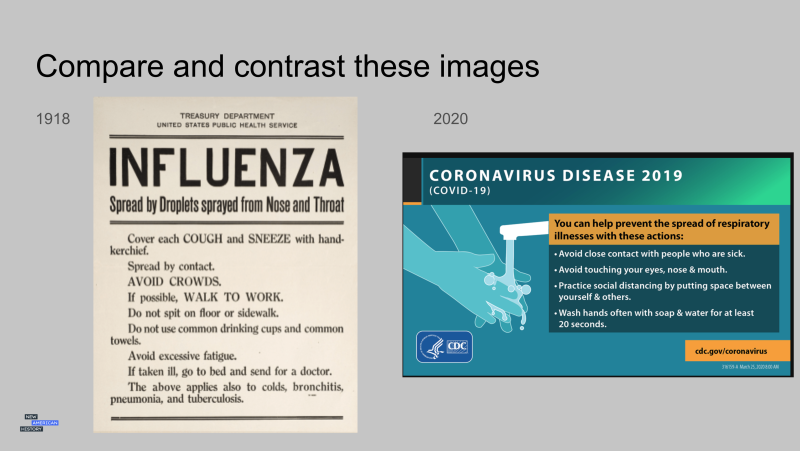

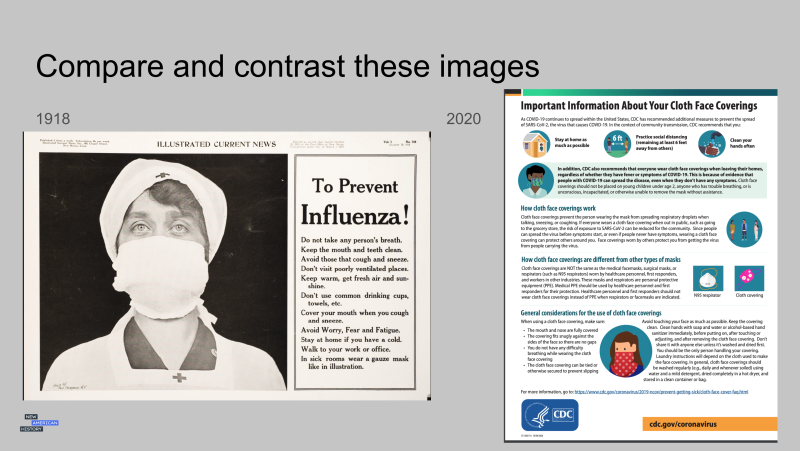

Compare and contrast some of these public service announcements from both pandemics. Discuss these with your parents, or share and discuss with an older relative or family friend over the phone or via video conference.

- What do these images advise citizens to do to protect their own health and the health of others?

- How do the 2020 guidelines differ from the 1918 guidelines? Why do you think these changes were made?

- How could these guidelines help citizens make informed decisions about when it is safe to “return to normal?”

- Do we need more information to make an informed decision based on these images?

- Where might we find more information?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

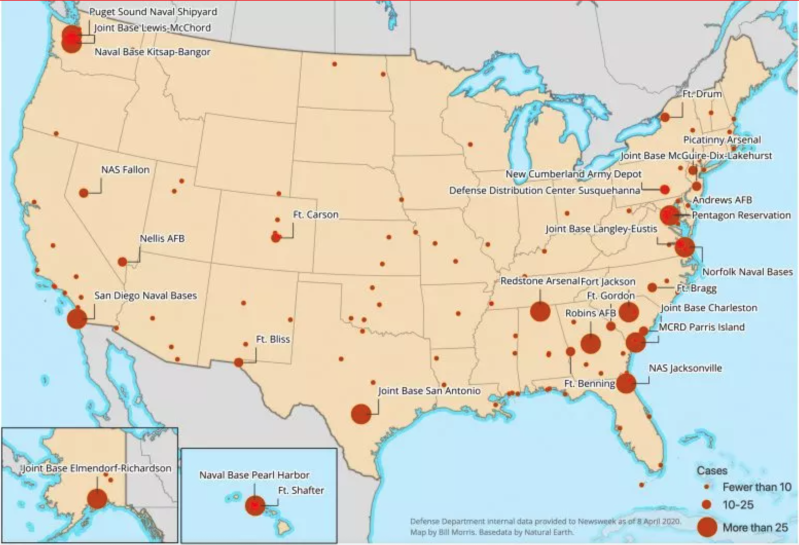

How do doctors, scientists, and cartographers use historic data, scientific evidence, and maps to track and stop the spread of a pandemic?

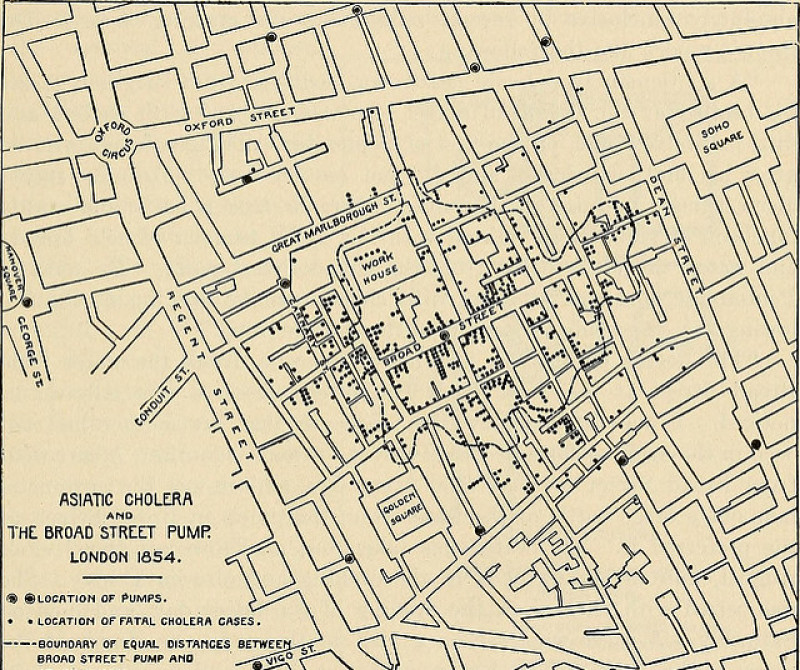

Long before scientists, doctors, and cartographers had access to computers or the Internet, they used data collection and maps to solve medical mysteries and find cures for diseases. Before the 1918 flu pandemic, John Snow, a doctor in London, England, used medical geography to study an 1854 cholera epidemic. Snow collected data and used a hand-drawn map to trace each victim’s steps to a single water pump. He was the first doctor known to have used maps and tracing to solve a medical mystery. His methods include posing some basic questions still used today by doctors, scientists, and cartographers who create digital maps to help solve medical mysteries, trace the origins of an outbreak, and stop the spread of diseases.

- WHO is sick?

- WHAT are their symptoms?

- WHEN did they get sick?

- WHERE could they have been exposed to the cause of the illness?

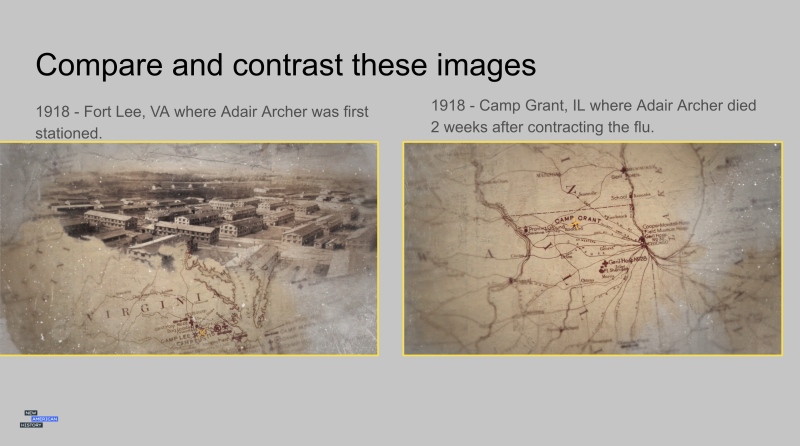

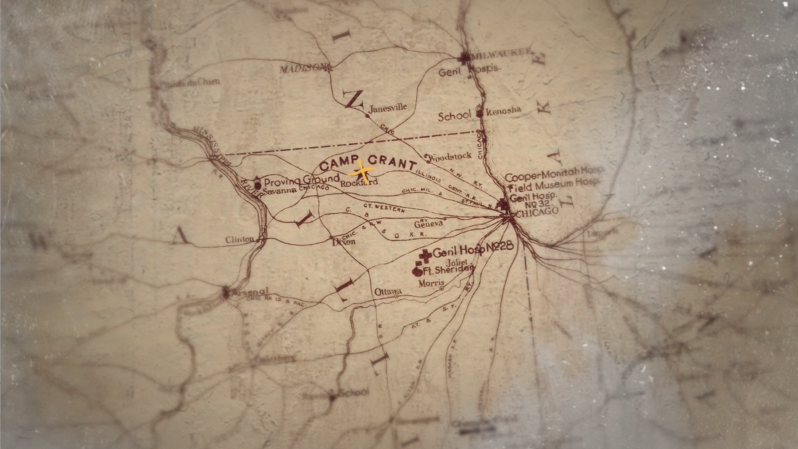

In this next segment, we see one story of a soldier who fell ill with the flu as he was preparing to serve in World War I. (View video segment, “A Soldier Falls Ill.”)

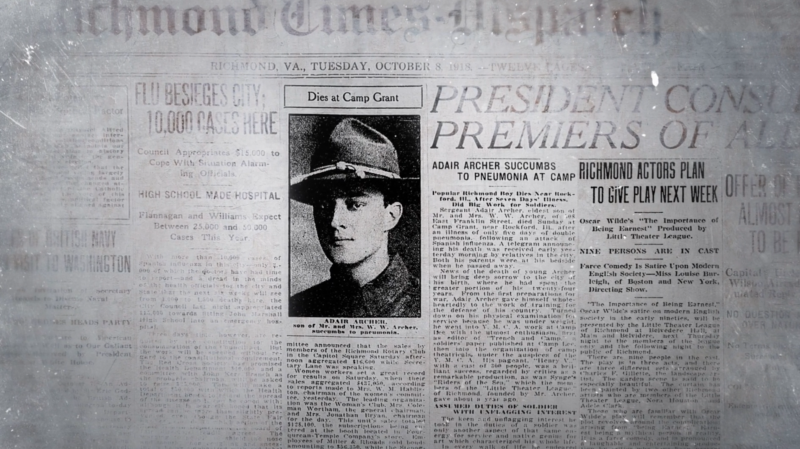

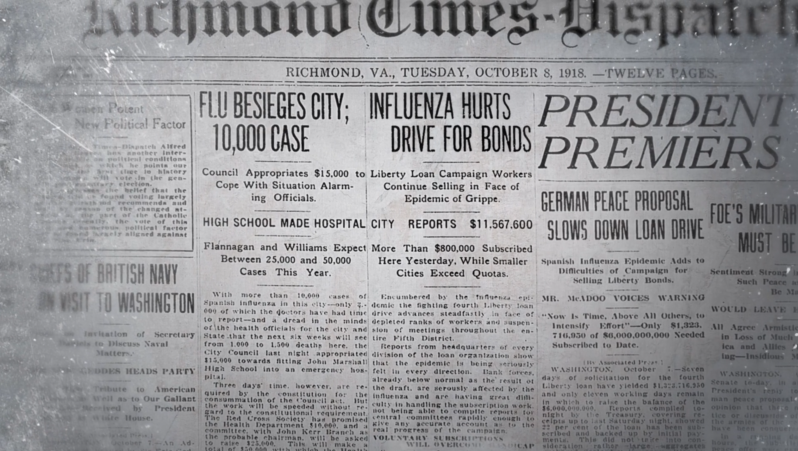

When the flu pandemic spread across communities during World War I, hospitals were unprepared. They were under pressure to contain it as quickly as possible. Study these headlines in the news, and the story of Adair Archer, then consider the following:

- How did the business community respond to the flu epidemic in Richmond?

- What were policymakers and politicians most concerned about based on the news reports about the flu epidemic in Richmond and across the country?

- How did the flu impact the citizens of Richmond, Virginia in 1918?

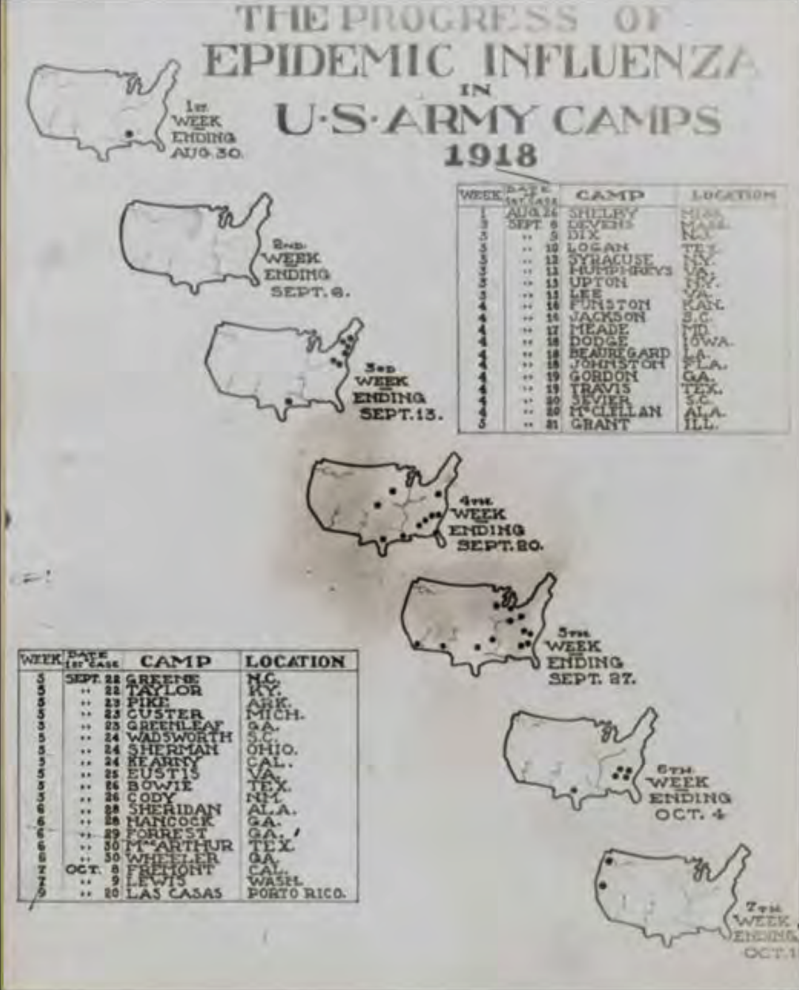

While many longed for a return to “normal life,” the pandemic had other plans for doctors in Richmond, Virginia and across the country. Just as John Snow had traced a cholera epidemic decades before, scientists and doctors looked for patterns and began tracing data as the flu spread. People who worked in low-wage jobs, those who cared for the elderly, and those who lived in dense communities like military bases were especially hard hit. Medical records were used to compile data and begin mapping out the spread of the disease.

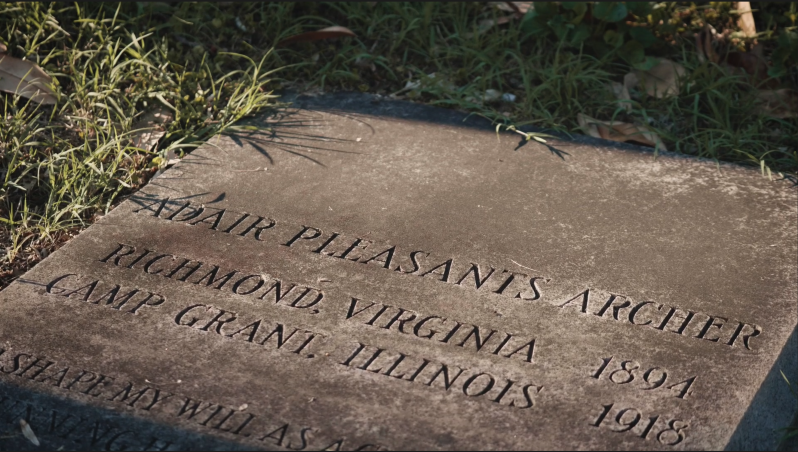

As the media began reporting news of widespread illness and death, communities like Richmond were overwhelmed with the loss of loved ones. Adair Archer was a soldier, and a beloved son. He wrote plays, and supported women’s suffrage. He became ill after a transfer to a military base in Illinois. His parents, family, and friends back in Richmond, Virginia, were devastated when he died shortly after contracting the flu. As schools and businesses remained closed, and public health officials recommended social distancing. The City of Richmond saw infections climb between October and December. The death toll nationwide was greater than the number of U.S. casualties in World War I and World War II combined. Greater than the number who died from the 1918 flu in the United States, as more than the total number of deaths due to AIDS since HIV appeared in the 1980s.

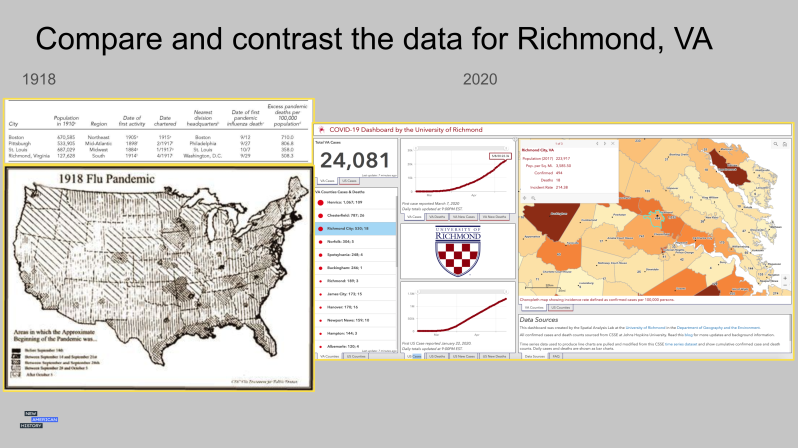

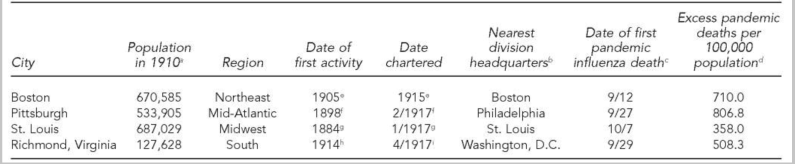

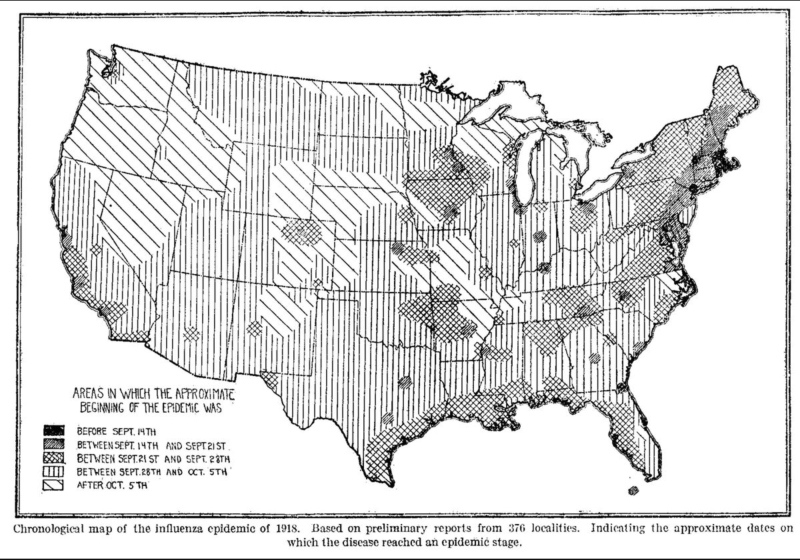

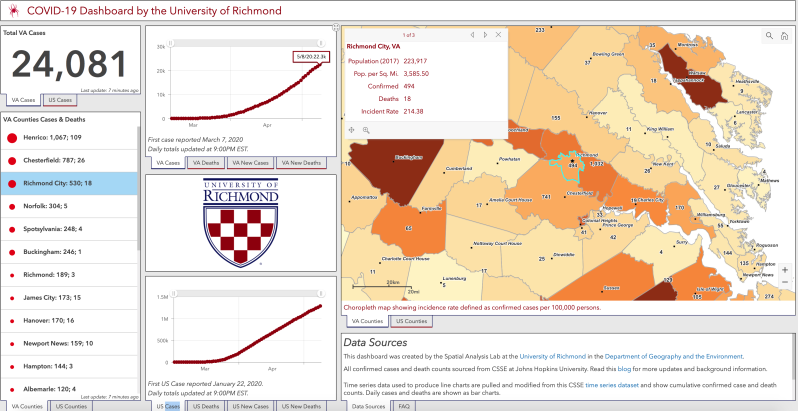

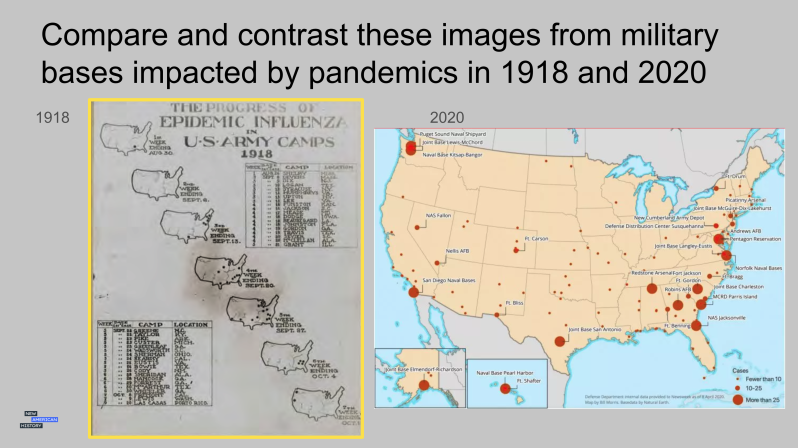

The images below help us to see the types of data and maps health officials used during the 1918 flu pandemic. Today, technology helps speed up the process for identifying, tracing, and treating COVID-19. Using digital tools including spreadsheets, digital maps, and video conferencing, information is now shared among doctors, scientists, and cartographers who are treating patients on the front lines as well as those urgently searching to develop a global vaccine.

- How do the methods and types of data in each of the images compare between 1918 and 2020?

- What role has visualizing data and technology historically played in how scientific research is conducted during a public health crisis?

- How do the media, the government, and the scientific community communicate public health information?

- Where do most people get their information about COVID-19 today?

- How can citizens determine the most accurate sources for information about public health during a pandemic?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

In what ways does structural racism endanger the health and safety of people of color?

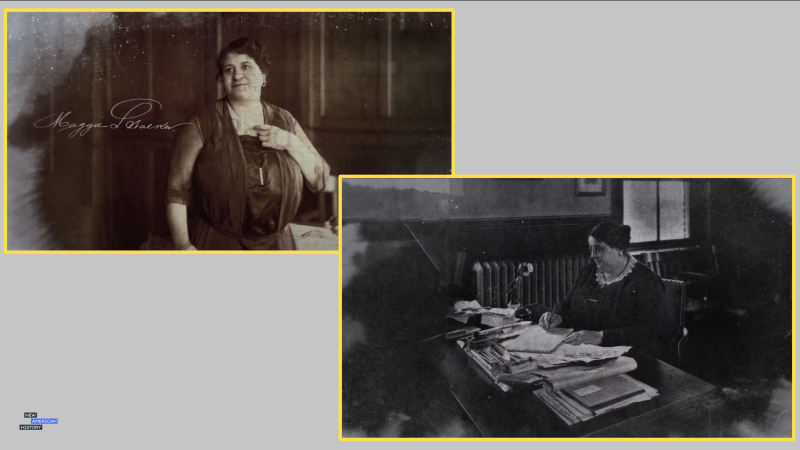

Richmond has no memorials to the survivors of the1918 flu pandemic. No plaques or buildings to honor those who were lost. No statues honoring those who served on the frontlines as doctors, nurses, and medical volunteers. But National Park Service rangers help to tell this story at the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site.

Maggie L. Walker, primarily known as the first African American to charter a bank, championed the cause of social justice by helping to develop black businesses and promote opportunities for people of color to gain access to education, health care, jobs, and affordable housing. (View video segment, “The Fight for Equal Treatment.”)

When the flu hit Richmond in 1918, hospitals were quickly overwhelmed. Richmond city officials turned a white high school into an emergency hospital with segregated wards. The white patients were treated in the upper floors of the building, where they could recover with plenty of fresh air and sunshine. Black patients were crowded in the basement, with no windows to circulate air. This prolonged their illnesses and led to greater suffering and potentially death.

Compare and contrast these historic images. What evidence do you see of structural racism?

“When you're battling a disease such as the flu, what is going to help you most are being in airy places, being where sunlight is. A basement is going to be a place where the suffering probably would be compounded. So they did something to have an emergency hospital set up, but they couldn't overcome segregationist tendencies.”

One possible solution suggested was turning the Baker School, an African American school, into an emergency hospital to better care for black patients suffering from the flu.

Maggie Walker was a civic leader and very respected in the community. She established the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903, led the Council of Colored Women, and helped to direct several other important organizations. As the 1918 flu swept through Richmond, Walker contacted the governor. She convinced him to establish an emergency hospital for black patients. In that hospital, black doctors and black nurses attended to the patients. Thanks to Maggie Walker's leadership and the dedicated work of black doctors and nurses, African American flu patients received better medical care.

Much like COVID-19, the 1918 flu pandemic affected people of all races, ages, and socio-economic status. While African Americans were not given equal treatment in segregated hospitals, Maggie Walker secured better treatment for African Americans in Richmond. In the Jim Crow era, limited resources were not equitably distributed to people of color. Some of these equity issues continue today.

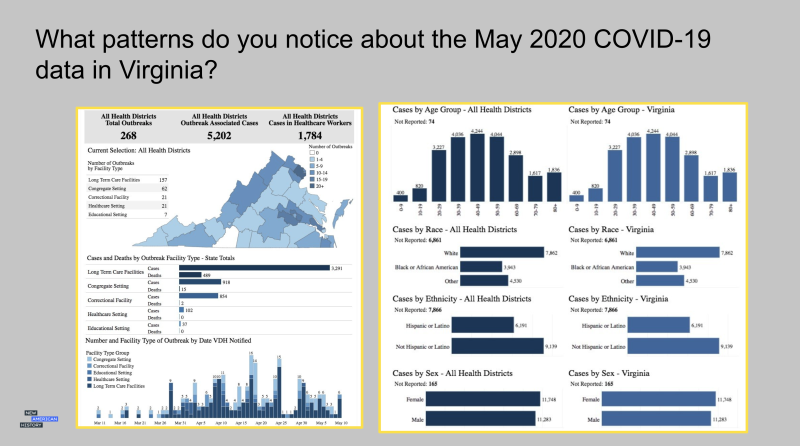

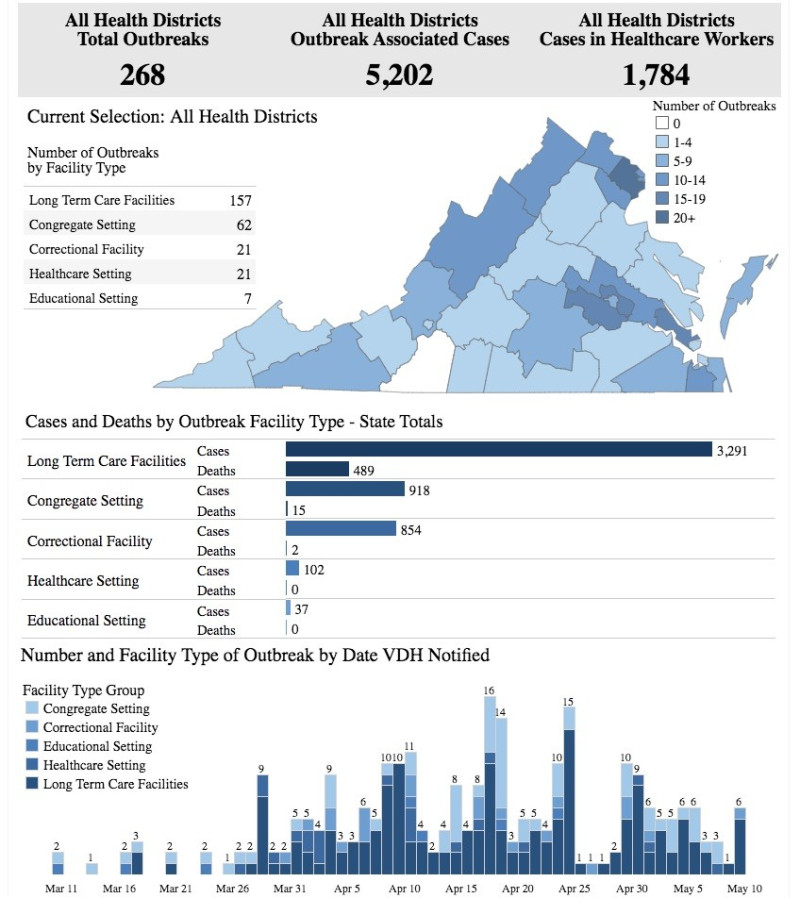

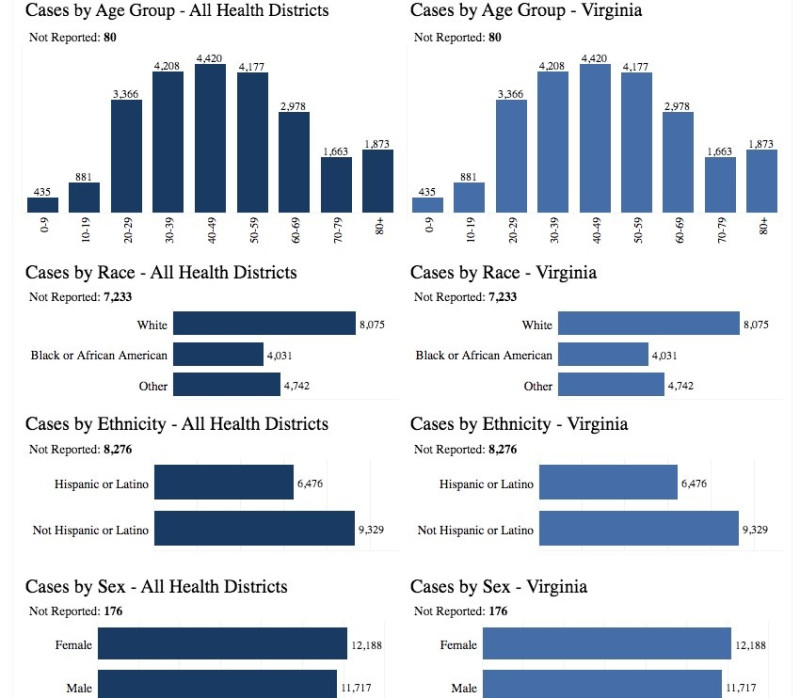

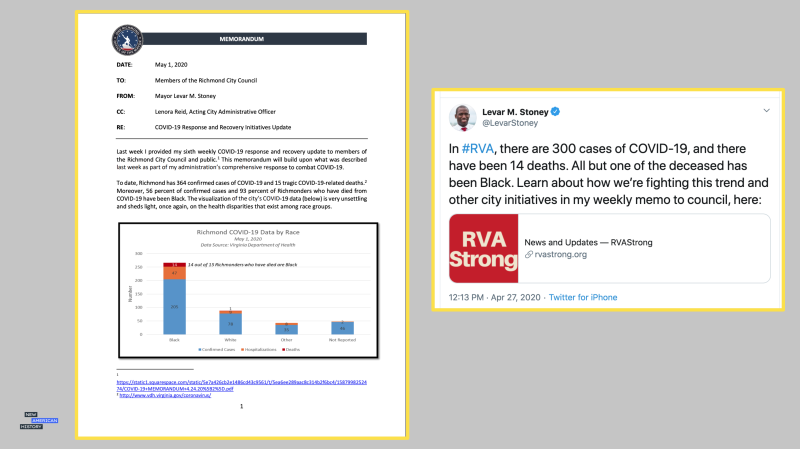

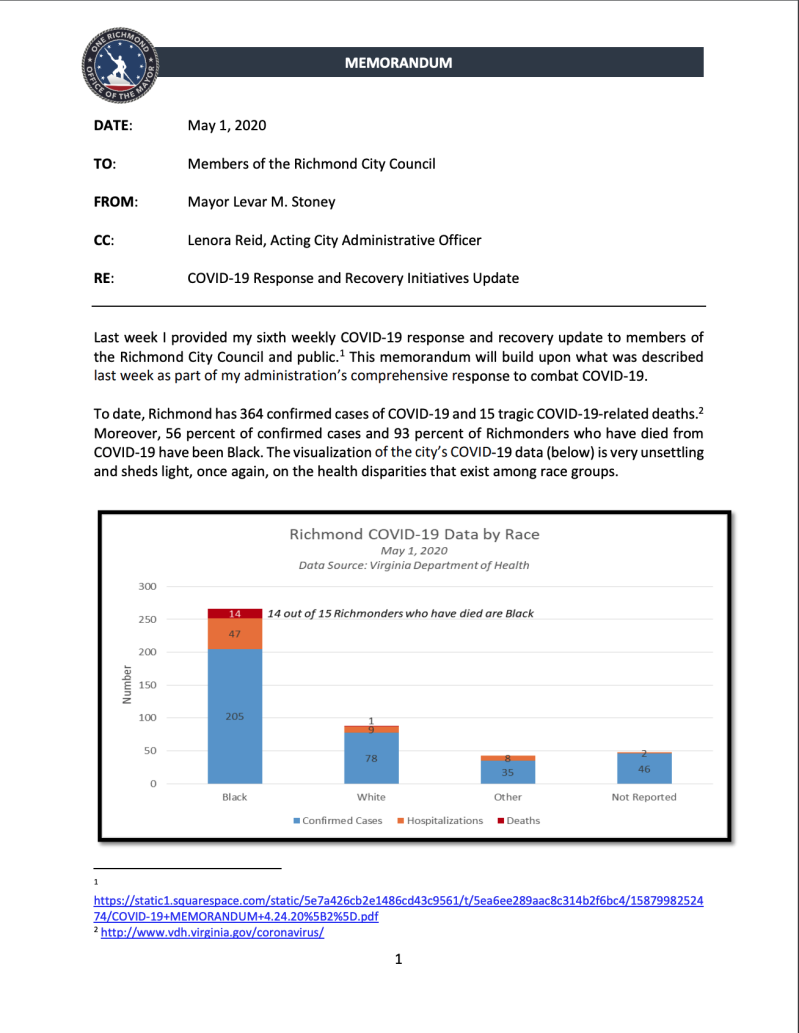

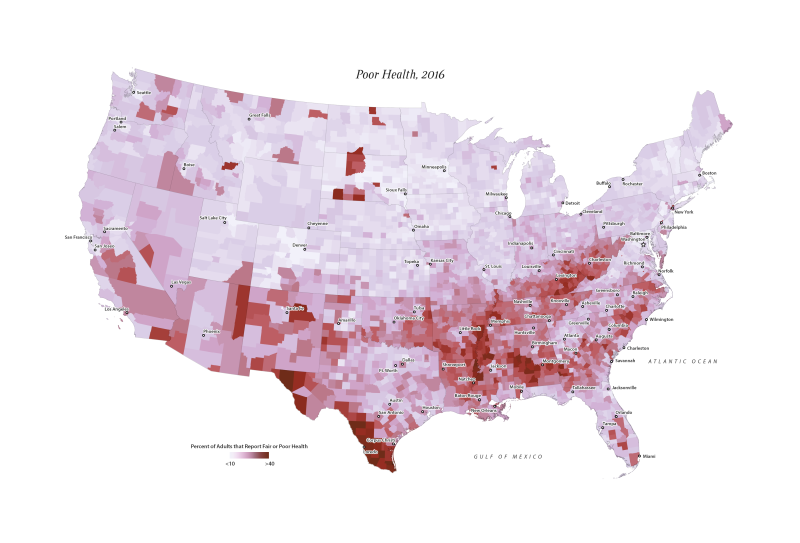

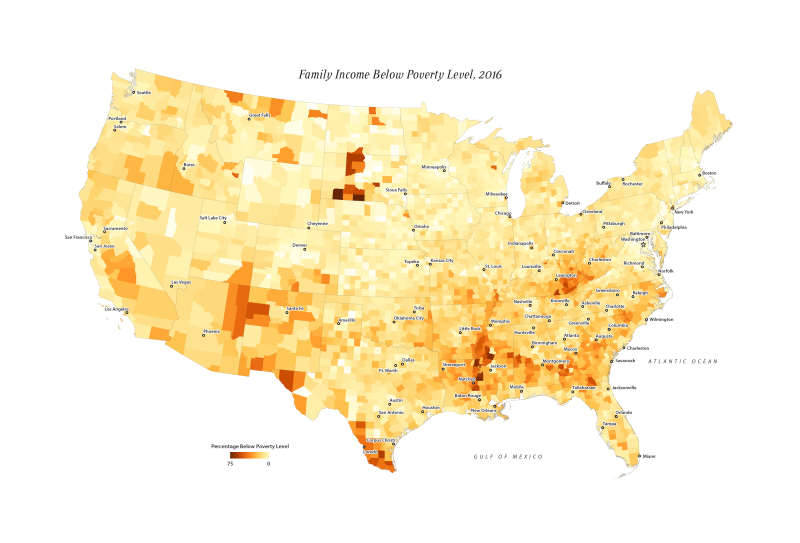

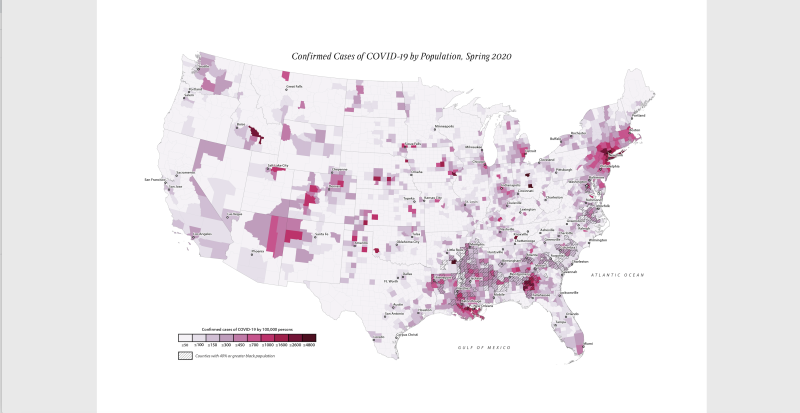

African Americans have gotten sick and died from COVID-19 at much higher rates than white Americans. This is due to generations of systemic racism and ongoing inequalities in accessing health care. People of color are more likely to work in high-risk industries such as agriculture, home health care, and warehouse and delivery work. They are less likely to have paid sick leave. They are less likely to work jobs which may be done remotely from home without interruption to paychecks and continued healthcare benefits. Minorities are also over-represented in incarcerated populations, who have high risk factors during public health outbreaks. Examine this data from the Virginia Department of Health.

- What patterns do you notice about the May 2020 COVID-19 data in Virginia?

- What factors seem to most impact the likelihood of contracting COVID-19 in Virginia?

- What data seems to be inconsistent or incomplete?

- What might be some reasons for this missing data?

Richmond’s mayor, Levar Stoney, shared data on May 1, 2020, that illustrates the greater risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 for people of color in the city.

Many politicians and civic leaders across the country have called for universal health care, and for Congress to raise the minimum wage as a pathway towards improving these equity issues.

Many Americans do not have health insurance and can't afford basic medical care. Others work at low wage jobs with few opportunities to earn a living wage. These problems often stretch over many generations within a family, and make it difficult for millions of Americans to stay healthy and survive a health crisis like COVID-19.

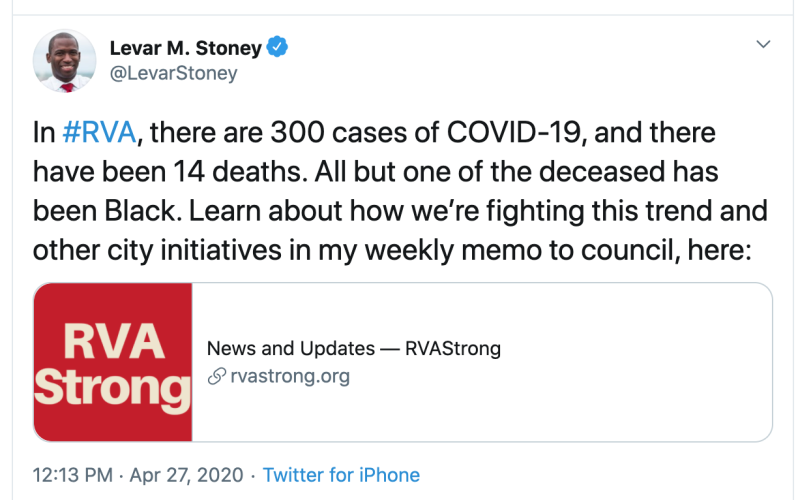

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic closed most U.S. businesses and has dramatically increased unemployment rates, once again drawing national attention to the widening economic and racial divide in America. These maps provide data on the scale of the problem across the nation.

- What patterns do you notice?

- How does this data compare with the 2020 data you viewed from Virginia?

- How does this data compare to the 2020 data you viewed from the city of Richmond, Virginia?

- How might you use your voice to help bring attention to these issues?

- What suggestions might you make, and to what persons or groups would you direct your solutions or suggestions?

Create a protest sign, infographic, or social media post, or compose an email/letter to share your concerns or seek more information based on the data you have seen. You may draw or paint your sign, infographic or social media post using materials you have at home (paper, crayons, markers). You could also create one of these options using magazine images or letters, or you may create these using a digital device.

Canva has free templates you may use for creating infographics and social media posts with a school Google login, or without email. Follow your parents’ or teachers’ guidelines on the use of social media before posting anything in a public format. We included some sample projects in the images below. With or without technology—be creative and most importantly, get your message across to your audience.

Here are some sample protest signs made by hand for an anti-gun violence student walkout in Richmond, VA from April of 2018.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket, in a journal, or post your work on a school approved platform such as Canvas, Google Classroom, SeeSaw or Schoology.

Elaborate:

Can America protect citizens’ constitutional rights and the general welfare during a pandemic?

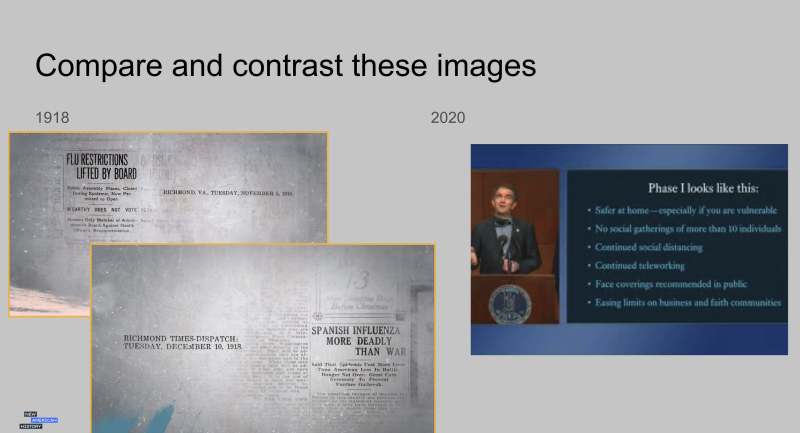

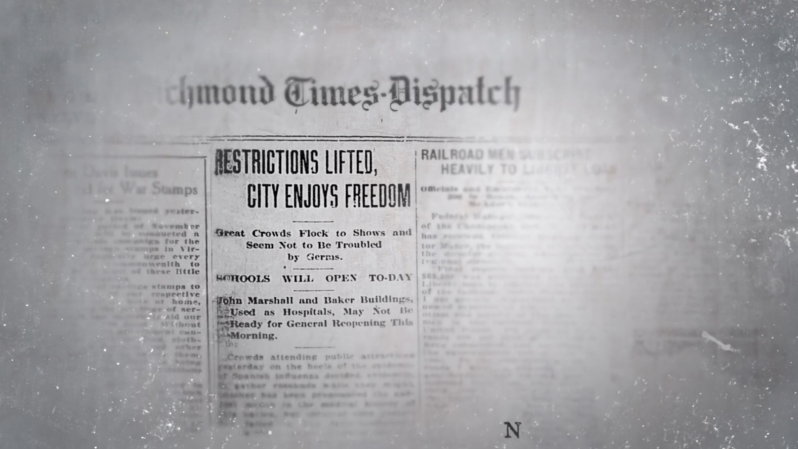

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt daily life in Richmond and across the globe, government leaders are forced to make difficult choices for the “common good.” With schools closed and unemployment rates surpassing historic levels, some citizens have begun to protest against social distancing at state capitols across the nation. Policymakers and public health officials faced similar pressures in 1918. (View video segment, “Opening Too Soon.”)

Richmond health commissioner Roy Flannagan was faced with a true life-or-death decision in the fall of 1918. He knew that large numbers of residents would get sick and many would die if businesses were allowed to reopen and normal life resumed. In fact, Flannagan’s own brother was terribly ill with the flu. But business owners told him they faced bankruptcy if they could not reopen. Medical experts initially persuaded Flannagan to hold off on lifting closure orders. But protests from business owners caused him to change his mind. Within a few weeks, the flu surged again, and many more died as a result. For Richmond and communities around the world, the 1918 flu pandemic proved deadlier than World War I.

“[T]he great majority of those present declared that it would be little short of a public calamity to reopen” businesses.”

In April of 2020, a rally held in Richmond, Virginia included protesters demanding the Governor reopen businesses and lift restrictions on public gatherings. Some wore masks and stayed in their vehicles, driving past the state capitol with protest signs. They wanted to make the Governor know they did not agree with the Stay at Home Order. Others took to the streets, with and without masks, claiming it was their Constitutional right. Some carried rifles, combining 2nd Amendment protests with anti-quarantine messages. Protests in other states, including Michigan, also challenged the constitutionality of a long term Stay At Home Order.

View these images from the 1918 and 2020 Pandemic news coverage. Pay careful attention to both the images and text. Look for examples or clues which reveal the various points of view in both eras towards the stay-at-home orders and decision-making process for reopening schools and businesses.

States are beginning to reopen, despite not meeting the Phase I guidelines issued by the White House and public health officials. Some localities are already starting to see a spike in new cases of the COVID-19. Americans have received mixed messages from lawmakers and leaders on both sides of the debate as states begin to ease restrictions.

Using the images from 1918 in the video and the 2020 news images, you will develop a short position statement from the point of view of one of the following individuals in Richmond, Virginia:

- Roy Flannagan, Richmond City Health Officer, 1918

- Governor Ralph Northam, 2020

- A theater owner demanding to reopen his business, 1918

- A beauty salon/barbershop owner worried about bankruptcy, 2020

- A nursing student treating flu patients in the basement of a hospital, 1918

- An ICU doctor treating COVID-19 patients on respirators, 2020

- A streetcar driver, 1918

- A grocery store clerk, 2020

Your position statement may be written in a reflective journal, or you may record it as an audio or video file. (We like SeeSaw or Canva!). Your teacher will work with you on the best way to share your thoughts, as told through the point of view of one of the stakeholders listed above.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

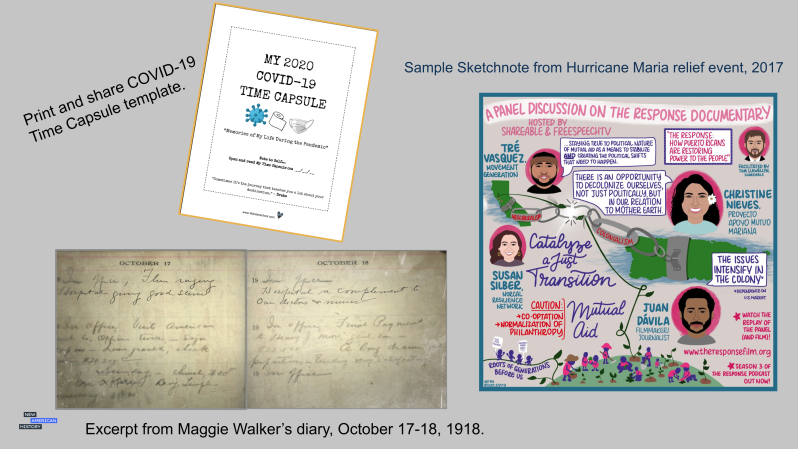

In what ways are we becoming the primary sources for future generations studying COVID-19?

Just as the 1918 flu pandemic was a global health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread to communities in almost every corner of the globe. Hospitals struggle to maintain adequate staffing as nurses and doctors on the frontlines are falling ill to the virus. Governors compete for access to ventilators, protective medical gear, and supplies for testing. Citizens grow impatient as there are delays in the supply chain for basic needs like food, toilet paper, and cleaning supplies. Some states seem determined to reopen sooner rather than later, despite warnings from experts on infectious diseases, and not meeting the established federal guidelines for reopening. The nation has been at this crossroads before, and we know how this story could likely play out based on history. (View video segment, “Crisis in Forgetting.”)

Take a few minutes to review some quotes and images from both the past and present pandemics. You may discuss these with your teacher and classmates remotely via video conference, or with your family. Your teacher may share the slides with you if you are unable to access them online.

“[T]he great majority of those present declared that it would be little short of a public calamity to reopen” businesses.

Sometimes, when walking down Broad Street, our main shopping center, I see it as it was then, feel that strange, whispering silence. This was an experience not forgotten by me.”

“This will not only result in needless suffering and death, but would actually set us back on our quest to return to normal.”

“My concern that if some areas cities, states or what have you—jump over those various checkpoints and prematurely open up, without having the capability of being able to respond effectively and efficiently, my concern is we will start to see little spikes that might turn into outbreaks.”

- What lessons might we take from the past in our current situation?

- What might “normal” look like in a post-pandemic world?

- How will schools adapt to the ongoing health risks to ensure student safety?

One way schools and museums have responded to the crisis is by encouraging students and their families to document their time spent at home while social distancing. Taking the lead from compelling historic narratives of past pandemic survivors, some schools are encouraging their students to keep a diary or journal, create a time capsule, or use Sketchnotes to show how their lives have changed since the pandemic began. You may use a notebook, drawing paper or your teacher may print and share a copy of the time capsule template--here are some examples to help get you to get started. Read these diary entries from 1918 for inspiration.

Museums and historic sites are also creating ways for families to safely share their reflections as a community, while others have created ways to share these stories on a larger scale.

Just as we began these learning experiences with a focus on one town’s story, The Valentine in Richmond, Virginia is preserving Richmond history. They invite students and their families to participate in the “Richmond Stories from Richmond Kids” project.

StoryCorps is a popular storytelling website that promotes the preservation and sharing of humanity’s stories through informal interviews and personal narrations that are recorded and archived to build connections between people and build a more just and compassionate world. Their “StoryCorps Connects” site encourages you to preserve your stories which will be archived by the Library of Congress. “Your interview becomes part of American history, and hundreds of years from now, future generations will listen in. We think of StoryCorps as an ever-growing archive of the wisdom of humanity.”

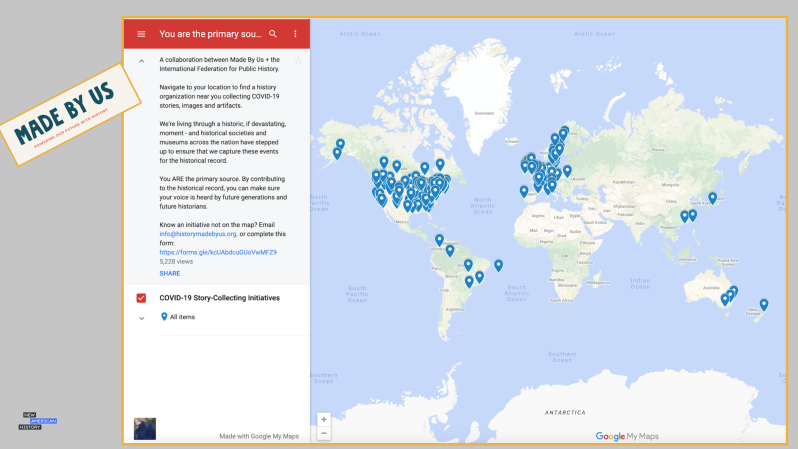

On an even larger scale, our collaborators at Made By Us are mapping story-collecting initiatives hosted by museum partners and history organizations around the world. “YOU are the Primary Source” provides resources for students and their families to curate their own artifacts, reflections, and images and share their collective experiences for future generations to study and learn from the COVID-19 pandemic.

- How will you document this time in your life?

- What stories will future generations learn from YOU?

- What lessons can we learn from the past and share with the future?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket or by selecting one of these ways to share your reflections on a larger scale.

Citations:

Ayers, Edward L. (Maps by Justin Madron and Nathaniel Ayers.) Southern Journey: the Migrations of the American South, 1790-2020. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020.

“COVID-19 in Virginia.” Coronavirus. Virginia Department of Health, March 2020. https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/coronavirus/.

“COVID-19 in Virginia.” The Virginia Public Access Project. The Virginia Public Access Project, March 2020. https://www.vpap.org/covid-19/.

“Dr. Anthony Fauci & CDC Director Senate Testimony Transcript May 12.” Rev. Rev Transcripts, May 12, 2020. https://www.rev.com/blog/transcripts/dr-anthony-fauci-cdc-director-senate-testimony-transcript-may-12 .

Llewellyn, Tom. “A Panel Discussion on Community-Led Disaster Response.” Shareable. Shareable.net, May 13, 2020. https://www.shareable.net/community-led-disaster-response-from-hurricane-maria-to-covid-19-a-panel-discussion-on-the-response-documentary/ .

Outka, Elizabeth. “1918 Richmond, VA Flu Pandemic.” 1918 Richmond, VA Flu Pandemic. Based on the scholarship of Richard Collier., n.d. Accessed May 2020.

“Public Health Matters Blog.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 14, 2017. https://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2017/03/a-legacy-of-disease-detectives/.

ReadWriteThink.org. Position Statements. PDF file. 2004. http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson394/position-statement.pdf .

“Richmond Stories from Richmond Kids Gallery.” The Valentine. The Valentine Museum, March 2020. https://thevalentine.org/studentstorygallery/.

“StoryCorps Connect.” StoryCorps. StoryCorps, March 2020. https://storycorps.org/participate/storycorps-connect/.

Stoney, Levar M. “City of Richmond.” City of Richmond. Office of the Mayor, May 1, 2020. https://bit.ly/2ARFuOg

“Student Journaling During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Facing History and Ourselves. Facing History and Ourselves, May 8, 2020. https://www.facinghistory.org/educator-resources/current-events/student-journaling-during-coronavirus-pandemic.

"The Future Of America's Past: A Public Calamity." 2020. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com/.

“Virginia Newspaper Project.” Library of Virginia | Virginia Newspaper Project. Library of Virginia, 1993. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/vnp/.

“FREE COVID-19 Printable Time Capsule Journal for Teens, Older Students.” Wanderschool. Wanderschool.com, May 7, 2020. https://www.wanderschool.com/2020/04/21/free-covid-19-printable-time-capsule-journal-for-teens-older-students /.

“YOU Are the Primary Source.” Medium. (History) Made By Us, May 7, 2020. https://medium.com/history-made-by-us/you-are-the-primary-source-211c33053bcf.

Zizzamia, Elizabeth. “COVID-19 Dashboard University of Richmond.” COVID-19 Dashboard by the University of Richmond. Spatial Analysis Lab, March 2020. https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/c2deeff0eb2947698145812037b71d14 .