This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Freedom's Fortress

Read for Understanding

Sometimes the people who write history take very specific perspectives, in fact you may know the phrase “who tells your story?”, which tells us that it’s important who is doing the story-telling or history writing. However, as time goes on historians are constantly working to uncover more stories that past historians might have missed. The story of the arrival of Africans in America is still evolving with more uncovered about our shared histories every year.

These Learning Resources may be adapted by your teacher and used in whole or in part, for large group or individual learning situations. Some activities are designed to include working with partners, or participating in a group discussion. For remote learning, your teacher may adapt these directions based on your school's policies and access to technology.

Key Vocabulary

Archaeologist - a person who studies human activity by discovering and analyzing artifacts, or evidence of material culture

Asylum - protection granted to a refugee, a person who left their country for fear of their own safety or the safety of others in their home country

Commemorate - to honor the memory of an important person or event

Consensus - a general sense of agreement or respect for opinions on a topic of discussion or debate

Contraband - property that is illegal to own or transport/smuggle; historically, during the U.S. Civil War a term used to describe escaped enslaved Africans given sanctuary by Union forces who declared them goods that may not be supplied by people who are neutral in a war

Fugitive - someone who escapes from captivity or the law

Landscape - the cultural landscape of a historically important place, including evidence of human interaction with the physical landscape or terrain, Earth’s surface

Material culture - the physical objects and structures people create and use in daily life (ex. artifacts, clothing, food, buildings, documents, tools, and technology)

Refuge - a condition of being safe; shelter from pursuit, danger, or harm (people who seek or take refuge are called refugees)

Sanctuary - a place of refuge or safety, historically often a church or government building where fugitives were protected from arrest or harm (ex. Sanctuary cities)

Secede - to break formal or political ties, to leave a governing group or nation (ex. The South seceded from the Union during the U.S. Civil War)

Viewshed - a geographic term to describe an area visible from a specific location

Engage:

How do we interpret multiple events that unfolded across a single historic landscape?

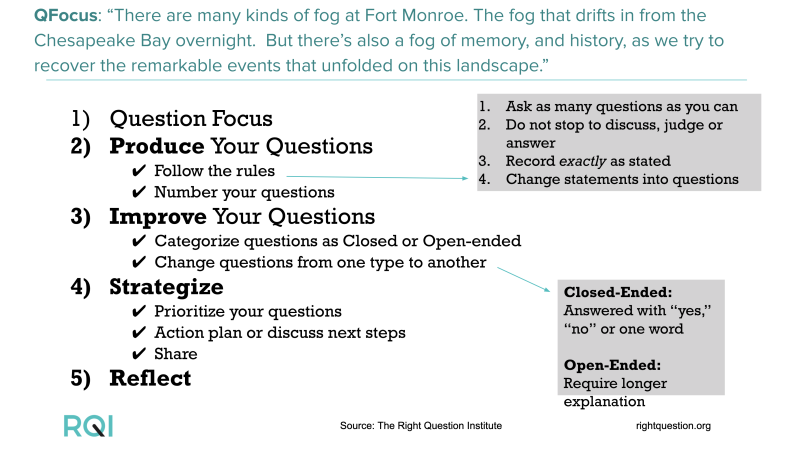

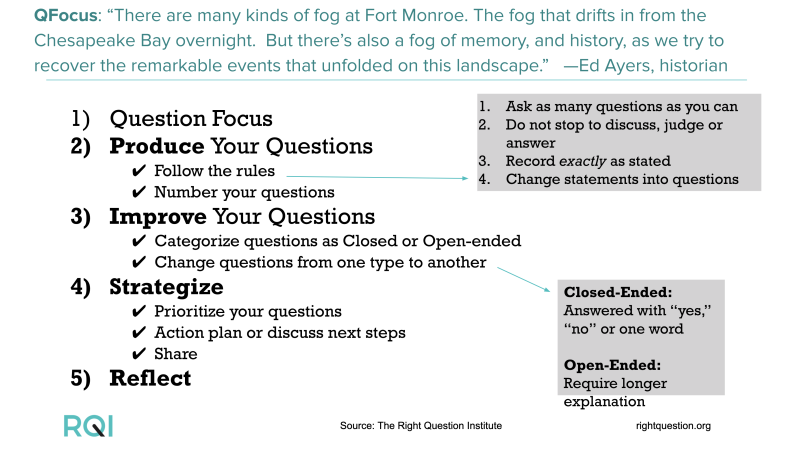

Use the Question Formulation Technique (QFT) to study this quote with your classmates. The teacher will introduce the first Question Focus, (or QFocus), using the quote on slide 1, and the rules for the exchange as posted below. If you are working remotely, you may work independently or, if possible, with a group via video conferencing.

The process may begin for a second round once you (and your classmates) conclude the first discussion with a second QFocus, this time using the second slide which includes the same quote with the speaker’s name now revealed.

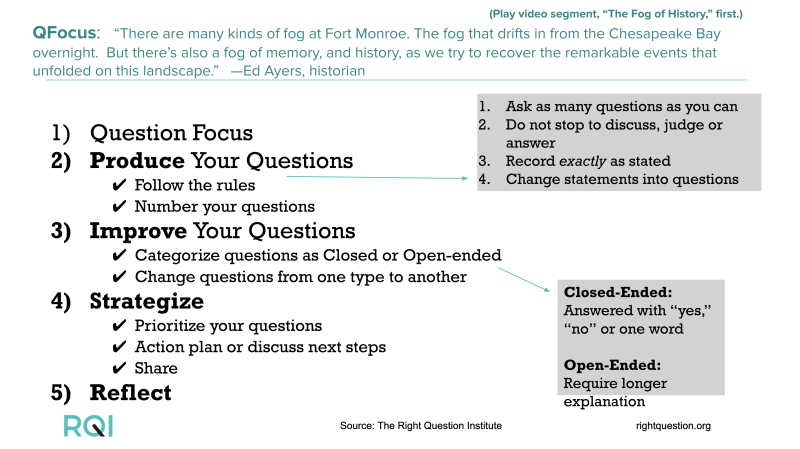

Once all students have examined one or both versions of the quote, take time to explore the original source by viewing the opening segment from The Future of America’s Past, "Freedom’s Fortress." (View video segment, "The Fog of History.") After you have viewed the segment, allow time for a final round of the QFT, using slide 3 with the video as the QFocus.

Follow the student-developed action plan to learn more about Fort Monroe. An exit ticket may be used, or a reflective journal for the last step of the QFT process.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore: How can visiting historic sites help us develop a Sense of Place as we explore physical and cultural landscapes?

In The Future of America’s Past, historian Ed Ayers visits places that define the most misunderstood parts of America’s past. In this segment, Ed visits Fort Monroe National Monument in Hampton, Virginia, and has a conversation with the National Park Service Ranger and Park Superintendent, Terry Brown, about the legacy of this historic landmark. (View video segment, "Making Freedom’s Fortress.")

Geographers often look at history through a specific lens, a Sense of Place, examining the human and physical characteristics of a place over time, noting what makes each location unique from all other points on Earth.

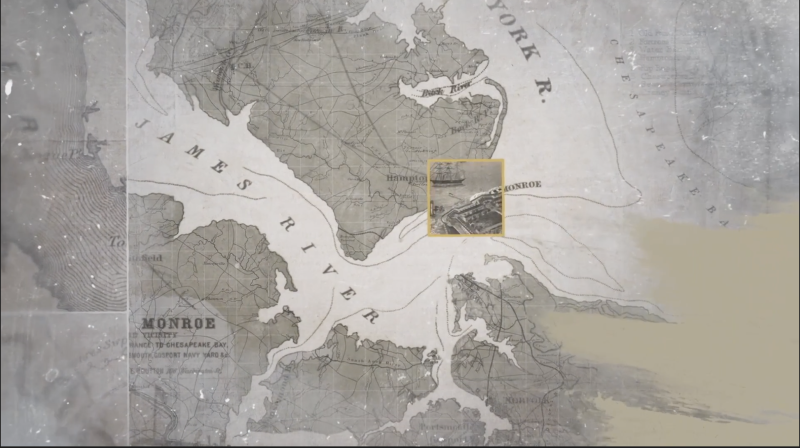

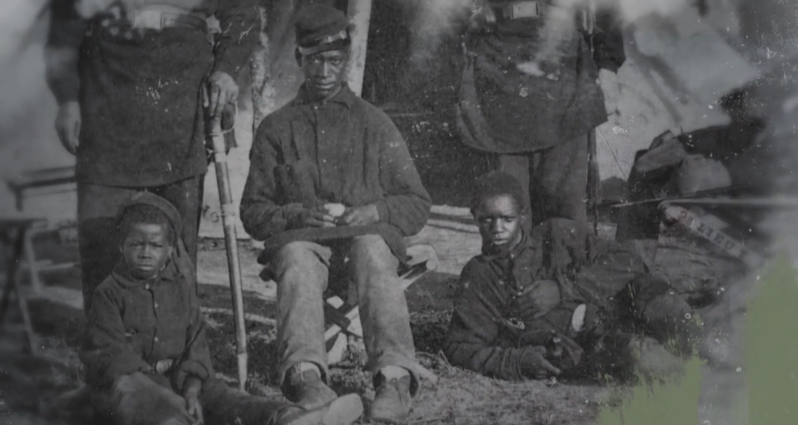

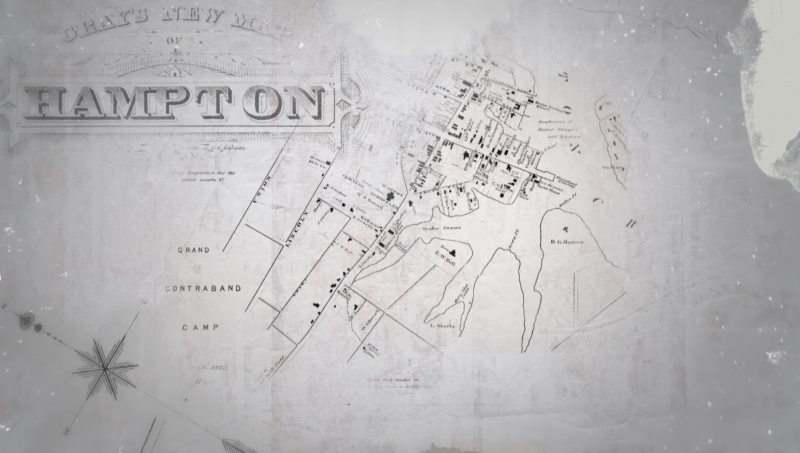

Examine these historical maps and images from the video about Fort Monroe. What clues do they provide to help us understand more about the people and events that shaped the physical and cultural landscape of this place over time? (You may also rewatch the video for additional clues!)

You may now work independently, in pairs or small groups to take a closer look.

- How might you sort these maps and images?

- What categories or labels would you assign to each map or image in this collection?

- Do the maps and images include any text or captions to help you interpret what you are seeing?

- What material culture is present in the images that might help us determine the approximate time period when these images were created? (objects, buildings, clothing?)

- Do the images or maps have any other clues to help us understand more about the place and time each image reflects?

Create a visual timeline using several of the maps and images. Your timeline should include significant events from the history of Point Comfort, now known as Old Point Comfort, and Fort Monroe. You will need to create short captions for each image you use from this segment of the episode of The Future of America’s Past. Your teacher may choose to print each map and image and have you sort them and create your timeline by hand like a museum exhibit, or you may sort them and create your timeline digitally as you might see on a museum website. This free timeline tool might help!

Once you are finished, share your timeline with one or more people, comparing their timeline to yours. Your teacher may allow you to participate in a gallery walk to view multiple timelines if space and time permit, or perhaps via a digital gallery walk.

- Do you see any similarities or differences between the timelines?

- Discuss how you (and your partners, if you didn’t work independently) decided how to categorize each map and image. What clues helped you decide how to place them chronologically?

- After discussing these differences, would you consider adjusting or reorganizing any of your maps or images on your timeline?

Now select 2-3 maps or images from the collection you are most curious about for further investigation.

- Who might have created these maps and images, and how?

- For what purpose do you think these particular images were captured?

- Where might you look for more information about the maps or images you selected?

- Create a more detailed caption, using historic information shared by Ed or Terry in the video, or from your own research, for each of the images you selected.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

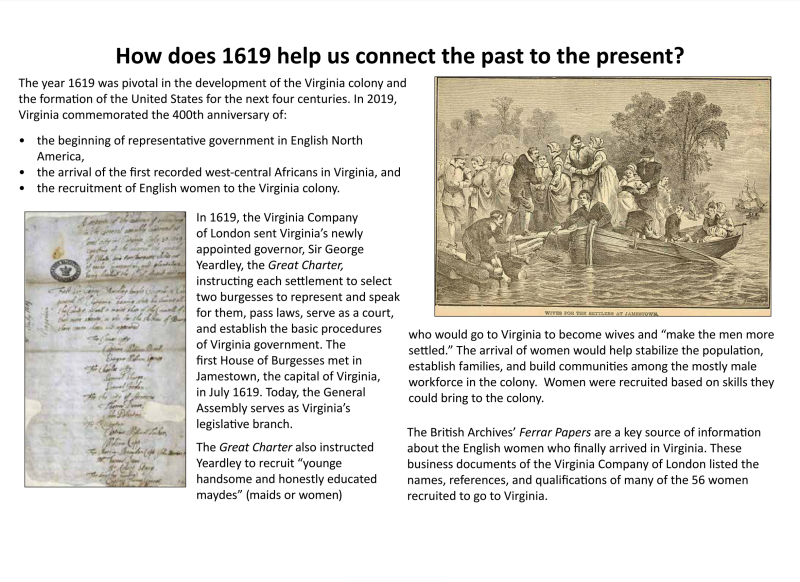

How does 1619 help us connect the past with the present?

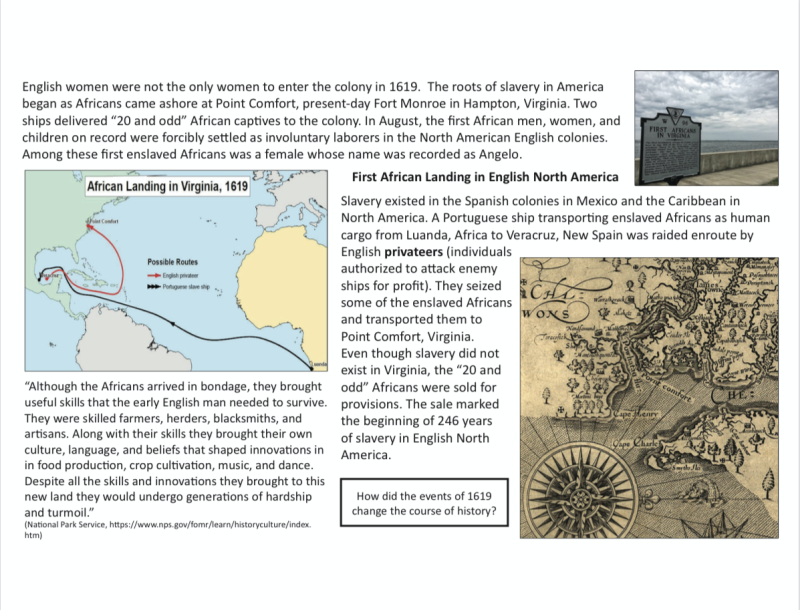

When the first English explorers came to Virginia in 1607, they discovered a Native American fishing village inhabited by the Kecoughtan near the site where the James and York Rivers flow into the Chesapeake Bay. Recognizing this strategic location had value as a viewshed, or “early warning site” for ships entering the bay, the early settlers called this area Point Comfort. By 1619, when the first Africans landed in British North America, Point Comfort was the entry point for all ships entering the harbor. Starting in 1861, it was the site where slavery began to unravel.

In this segment of The Future of America’s Past, historian Ed Ayers spoke with Calvin Pearson, a community leader in Hampton, Virginia. Calvin describes the grim legacy of slavery, and how he and others commemorate the arrival of the first Africans and honor their ancestors. (View video segment, "Remembering a Beginning.")

In this segment, Calvin Pearson makes an important distinction about the way we commemorate, rather than celebrate, the events of 1619.

“So what we tell people when they come here today, in past years and in the future, is that this is a commemoration, it's not a celebration. We do not celebrate slavery. This is a commemoration of the arrival of the first Africans. But we also want to celebrate 400 years of history. Because if you look at a people who are brought here against their will and in chains, who eventually help build this great nation, this is still our country too. This is a sacred place for us. When we walk these grounds, we feel the spirit of our ancestors. So that's why it's so special to us.”

In 2019, communities across Virginia and the United States commemorated the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first Africans in North America. The ceremony was held at Fort Monroe, at the site now known as Old Point Comfort. In the video, you saw how Calvin Pearson and other members of the African American community commemorate this event every year.

Read this excerpt and study the maps and images from An Atlas of Virginia, shared by the Virginia Geographic Alliance.

Turn and talk to a partner:

- How did the events of 1619 change the course of history?

- Explain what you think Calvin Pearson means when he states in the video, “...this is a commemoration; it’s not a celebration.”

- What other historic events, people, or places do we commemorate?

- Are there certain historic events, people or places we do celebrate as a community? A state? A nation?

In August of 2019, the New York Times published The 1619 Project, a special issue of their magazine. The project also includes a kids’ section, What You Should Know About 1619, for younger readers. The editor stated the goal of the project is to “reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.”

The 1619 Project includes images, poems, short stories, and essays. It was written by African American historians, journalists, and artists. They make the case that the founding of America was rooted in slavery. The authors encourage readers to think about how generations of black Americans have been denied basic human rights, even after slavery was abolished. These include freedom, citizenship, education, fair job opportunities and basic medical care. Many of these ideas have not been discussed in detail in most history classes.

Some historians and politicians have been critical of The 1619 Project, arguing the authors are trying to “rewrite history.” Some thought that the project is too negative, and that it ignores the progress that the nation has made toward equality. Others thought the project made historical errors. Some disagreed with The 1619 Project’s claim that the founding fathers fought the American Revolution mostly as a way to preserve the institution of slavery for their own financial and political benefit. The New York Times published a letter from five historians who criticized the project in December 2019. In February of 2020, another group of critics launched their own website to present their arguments, The 1776 Project.

On both sides of the debate are historians, politicians, teachers, students, and parents. No matter where you stand on this ongoing debate, one thing is clear: the controversy has led to more people thinking and talking about history. The 1619 Project is not just about memorizing facts. It motivates us to discuss how we teach and learn about slavery. It reminds us the legacies of slavery are still with us today, and we must teach a history that includes people from all races, religions, genders, and social classes.

Take a moment to reflect on the significance of the people and events that helped shape our nation. Turn and talk to a partner, or use a reflective journal to address the following questions:

- Was America built on the idea that “all men are created equal?”

- Who gets to decide what version of history is taught in schools? In textbooks? On TV, in movies or at museums?

- How do we continually rewrite our telling of the past, and why?

History is happening all around us, every single day. We are always finding new clues about the past, and discovering new ways to think about the people, places, and events we thought we already knew about. Maybe that is where they got the title, The Future of America’s Past.

Create a One-Pager to share your reflections on what you have learned about the significance of the events of the year 1619. You may choose to investigate and weigh in on your own thoughts about the controversy over the 1619 Project or the reading from An Atlas of Virginia. You will also want to share your thoughts about the video segments you have viewed from The Future of America’s Past. Your teacher will provide an opportunity for you to share your work and learn from your classmates by participating in a Consensogram.

A Consensogram is similar to a gallery walk, but this time you will give your classmates feedback by placing sticky notes or emojis next to ideas you agree on (use an “A” or thumbs up emoji”), respectfully disagree on (use a “D” or thumbs down emoji) or find interesting / challenge your own thinking (use a ”?” or a thinker emoji and add a comment to clarify). Once everyone has weighed in with their opinions, you may revisit your own One-pager to view comments and answer questions. A Consensogram is not designed to persuade everyone to adopt the same viewpoint but is a way to encourage civil discourse in a respectful way, and perhaps bring a group to consensus or a general agreement on a topic of discussion.

This may be completed digitally using a collaborative slide deck such as Google Slides where each person uploads their One-pager to a slide and classmates leave feedback using the comment feature or presenter notes area below each slide.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket or accept your One-pager as an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

Does commemorating the past and preserving our history get in the way of progress?

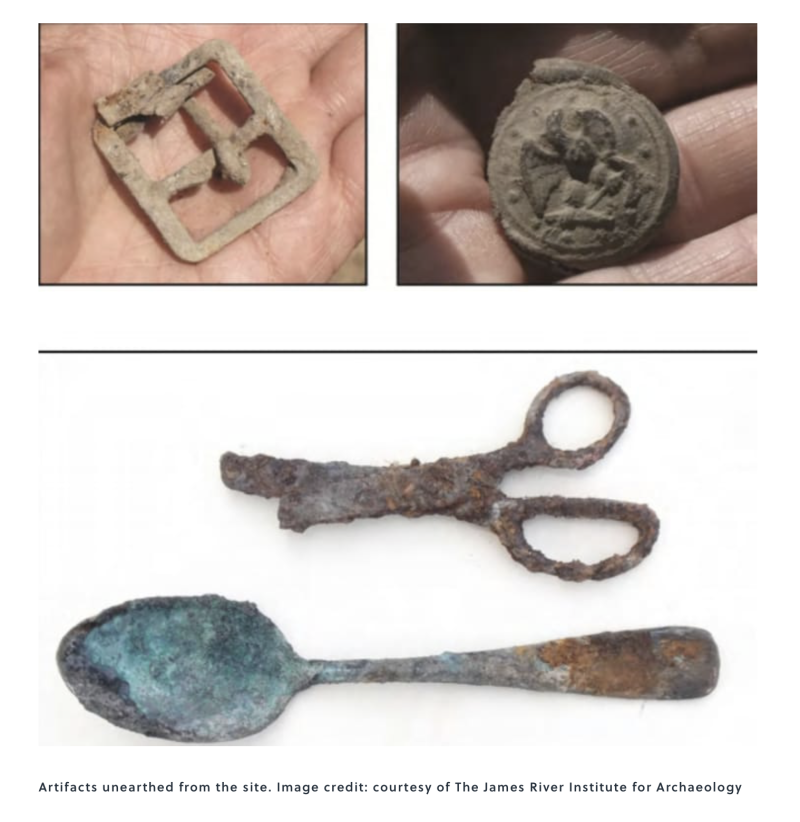

Archaeologists like Matt Laird study human activity by recovering (digging up!) or analyzing material culture, including artifacts, documents, and buildings. In this video segment, historian Ed Ayers meets up with Matt to discuss the artifacts he and his team discovered as they explored an historic neighborhood in Hampton, Virginia, just outside of Fort Monroe. Once known as the “Grand Contraband Camp,” it was here that African Americans built a community after the Union army and United States government provided refuge, or sanctuary for runaway enslaved African Americans at Fort Monroe. Nearly two years after three men first escaped to Fort Monroe, the Emancipation Proclamation officially changed the game, declaring slavery abolished in the rebelling states. The courage and sacrifices of those who sought refuge here showed President Lincoln that formerly enslaved people were not fugitives: they were allies. (View video segment, “Unearthing the Past.”)

Turn and talk to a partner about the work of archaeologists like Matt Laird as observed in the video.

- How do archaeologists use material culture to piece together new narratives about the past?

- What specific examples of material culture did Matt and his team collect?

- Where could you go to find out more information about the Grand Contraband Camp and the artifacts recovered there?

In the video, Matt Laird discussed the historical and scientific value of retrieving and preserving historical artifacts and showcasing them in museums and historic sites. Not all members of a community are always in agreement on whether or not we should spend money and use resources for historic preservation. Some people would like to keep these physical and cultural landscapes untouched, while others would like to see them developed or repurposed into new spaces, arguing that it is “progress.” Often, they come together to discuss their concerns, hoping to come to a consensus for the common good of their community.

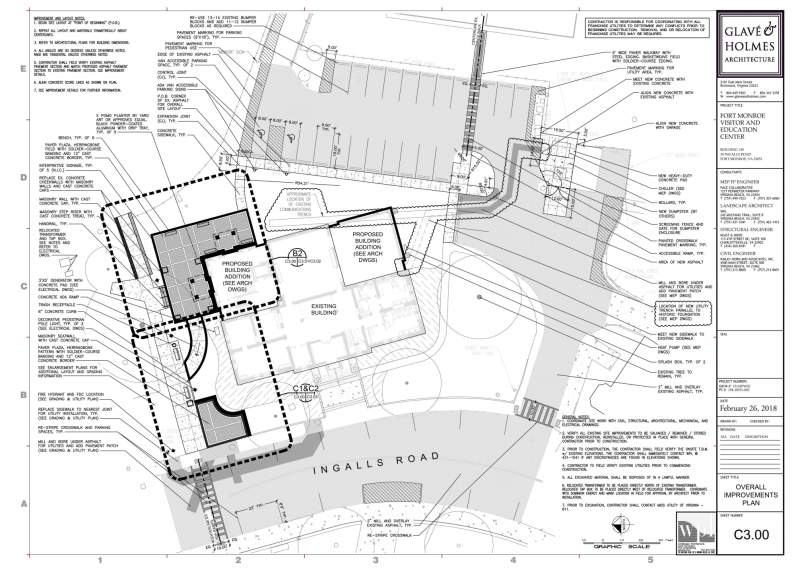

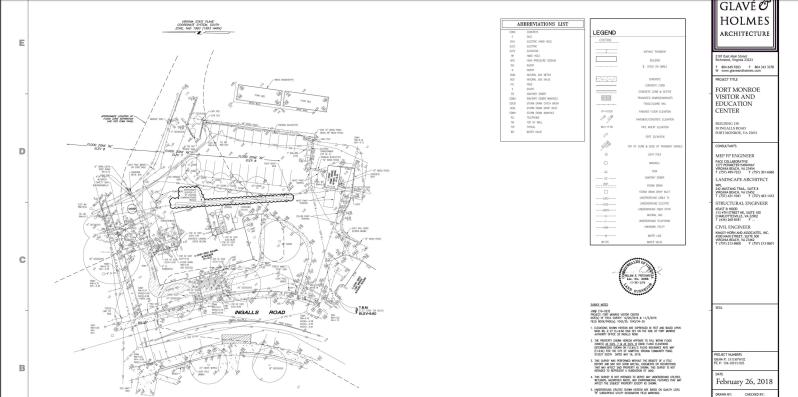

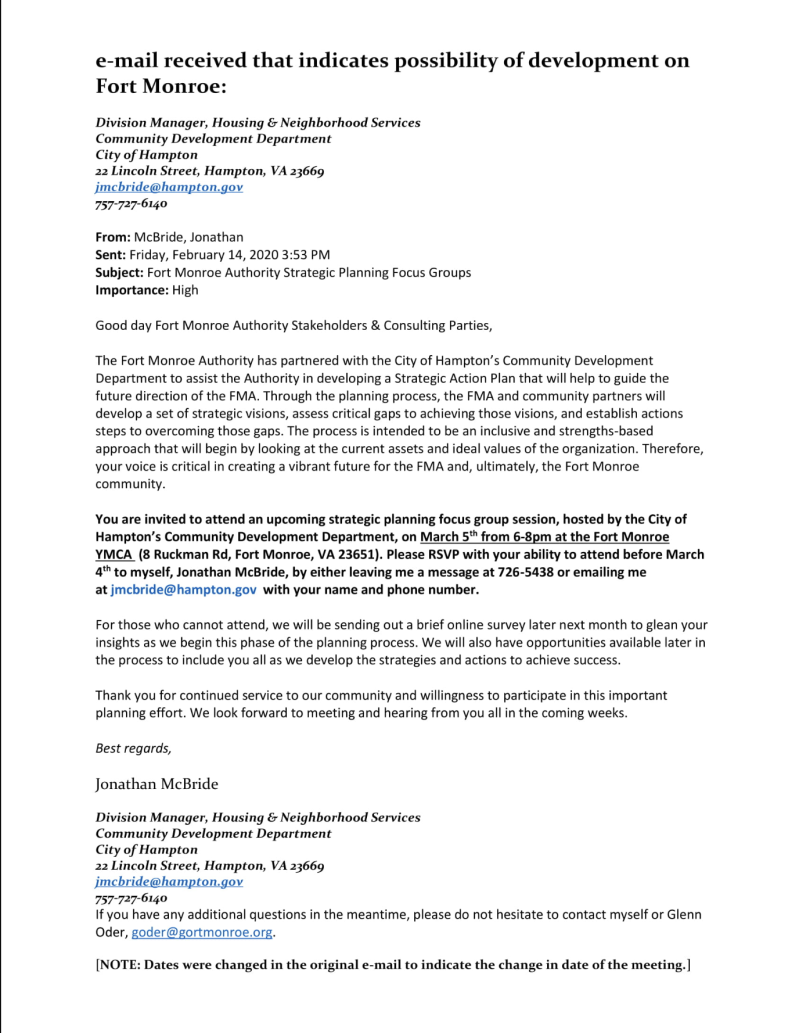

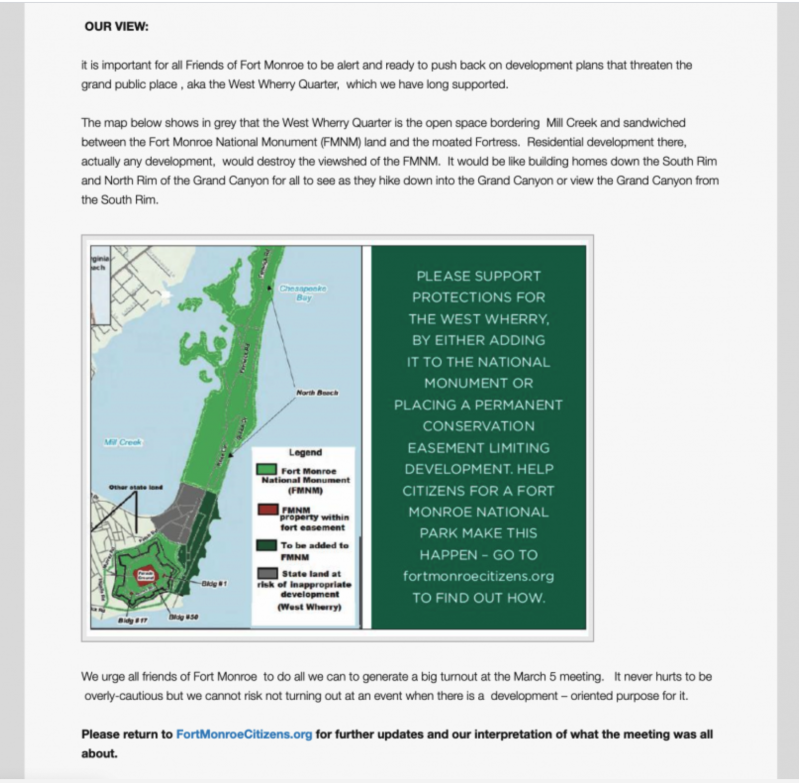

Take a few minutes to examine these documents. The first two are from a series of archaeological blueprints for a proposed new Visitor Center and Education Building at Fort Monroe. The next two are from a website created by Citizens for a Fort Monroe National Park, a local civic group of concerned stakeholders who are alerting their members about attending a public meeting to be held to discuss the proposed project.

You will participate in a Socratic Seminar with your classmates. There are many ways to organize these types of structured discussions, and your teacher will explain the directions they prefer. Your teacher will begin the discussion by selecting a student leader to facilitate the discussion. The student leader will pose an open-ended question, similar to the focus from an earlier learning activity in this Learning Resource.

Here are some suggested questions to guide the discussion if this is your first time participating in a Socratic Seminar:

Question #1: Does commemorating the past and preserving our history get in the way of progress?

You will participate in the discussion based on your teacher’s directions and the guidance of the student leader. These Question Stems might help you if you get stuck or need a prompt. The main rule is to participate thoughtfully in the conversation as both a listener and a speaker. If time permits, your teacher may offer a second round selecting a new student leader, using the following to guide the next round of the discussion:

Consider this statement from Archaeologist Matt Laird:

"We don't have to slow progress at all. And archaeology by its very nature is a destructive process. As we do these excavations, we're removing history from the ground, and in that sense we've essentially cleared the path for development. So it doesn't have to be an either/or. We can certainly gain the information and understand more about our history and our archaeological resources and still have progress at the same time."

Question #2: Can historic preservation efforts coexist alongside development without sacrificing progress?

Round 2 of the Socratic Seminar continues with students using examples from the earlier resources, including the blueprints and the website from the concerned citizens of the Fort Monroe community, along with this quote from Matt Laird in The Future of America’s Past.

At the conclusion of the Socratic Seminar, it is important to pause and reflect on your experience.

- How do you see your role as an active listener and participant in the discussion?

- How did you respectfully agree or disagree with other speakers?

- Did your thinking change as you explored the original question, “Does commemorating the past and preserving our history get in the way of progress?” or did it stay the same?

Your teacher may ask you to record your thoughts about the Socratic Seminar experience using a Reflective Journal or an exit ticket.

Extend:

How can we honor the people, places, and events woven into the fabric of our communities, and continue to make history every day?

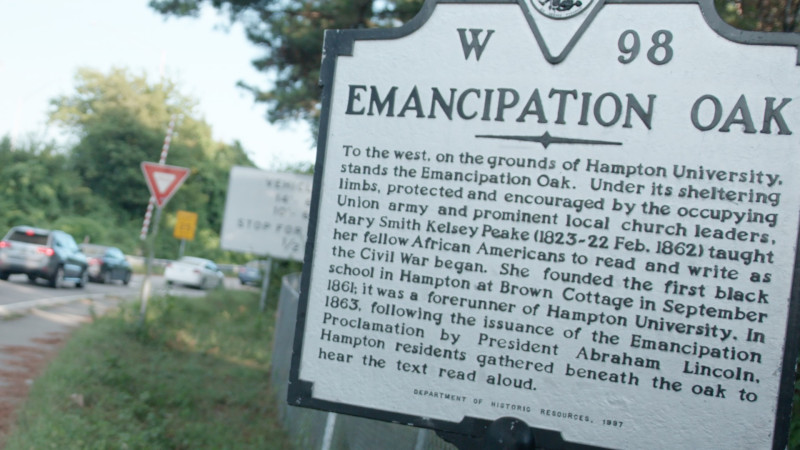

Colita Nichols Fairfax is an historian at Norfolk State University. In this segment of The Future of America’s Past, historian Ed Ayers visits Colita and learns about Emancipation Oak, a historic symbol of freedom on sacred ground within the African American communities in Hampton.

While viewing the video, jot down some key words, phrases or ideas you hear. Sketch any symbols or images you see in the video that inspire you about the people, places, and events being described. (View video segment, "Emancipation Oak.")

After viewing the video, turn and talk to a partner (if participating remotely, consider collaborating via a video chat with a partner if your teacher allows). Share your sketches and notes with each other. If your teacher allows, you may go back and rewatch the video segment, pausing to note any words or phrases you’d like to remember. (You may turn off the sound and use the closed captioning feature for help with spelling or capturing a speaker’s exact words.)

- What word or phrase do you most remember from the video?

- Who are the people connecting this sacred space to the historic events which have unfolded in this community over the past few hundred years?

- What symbol or image was the most compelling to you? Explain your answer.

"We are on sacred ground. Here is where Emancipation Oak, as it is called, one of the great oaks in the world, according to National Geographic Magazine."

I think we talk about freedom only in a sense of escaping from a physical place, the plantation or a workhouse. But freedom, I think, the part that we're missing, really is what you are able to do to live out your cultural self, to be able to attend to your needs mentally and emotionally, is to live life on your terms.

Continue to sketch and jot down more words, phrases, and ideas as we visit with a few more members of the Hampton, Virginia and Fort Monroe community. In this next segment, Ed introduces us to the Tucker family. (View video segment, “Descendants of the First African American.”)

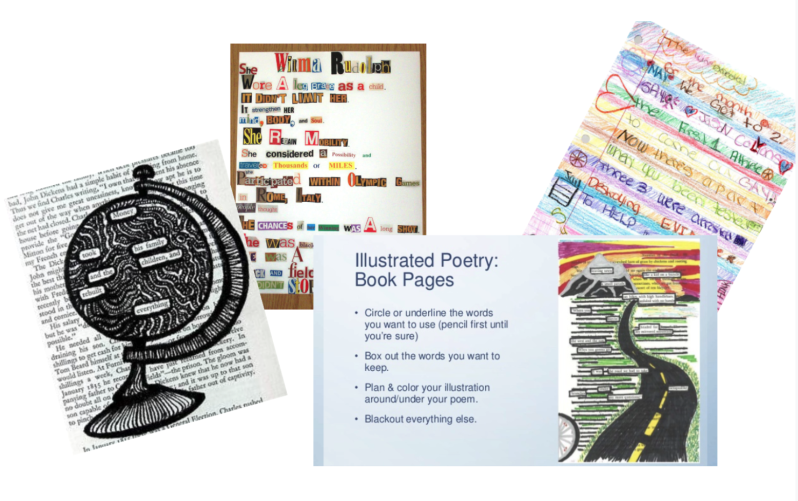

You will now create a Found Poem. Found Poems are based on words, phrases, text, images, and ideas. Use this video segment about the Tucker family from The Future of America’s Past, and any other video segments you have seen from this episode, to create your own Found Poem reflecting on the people, places, and events you have learned about from Hampton, Virginia, or Freedom’s Fortress and the beginning of slavery in North America. Here are a few examples of some found poems to help you get started!

Your teacher may provide you with an opportunity to share your poems either digitally, aloud or by displaying them in the classroom or school. An adult may help you share via social media as long as your name and image are not included for safety reasons.

History is all around us, and there are many stories still yet to be told, uncovered and retold from another perspective. Fort Monroe and Old Point Comfort have been the site of many historical events, some of which we commemorate and others we may honor or celebrate.

Your teacher may ask you to submit your Found Poem as an exit ticket.

Citations:

2010. Pdf. Hampton: Fort Monroe Authority. Viewshed Report. 2010. http://fortmonroe.org/wp-content/uploads/fort-monroe-historic-viewshed-report.pdf.

2020. Pdf. Hampton: Fort Monroe Authority. Http://Fortmonroe.Org/Wp-Content/Uploads/Appendix-B-Relevant-Drawings-For-Archaeology.Pdf.

2020. Pdf. Hampton: Fort Monroe Authority. http://fortmonroe.org/wp-content/uploads/06_1C-Natl_Historic_Landmark_District.pdf.

2020. Pdf. Washington, DC: Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/primarysourcesets/poetry/pdf/teacher_guide.pdf.

“Consensogram.” eduTOOLBOX. Ayers Institute, 2020. https://www.edutoolbox.org/rasp/2053?route=toolkit/list/assessment-for-learning.

“Empowering Students: The 5E Model Explained.” Empowering Students: The 5E Model Explained. Lesley University. Lesley University, 2020. https://lesley.edu/article/empowering-students-the-5e-model-explained.

Potash, Betsy. “A Simple Trick for Success with One-Pagers.” Cult of Pedagogy. Cult of Pedagogy, December 23, 2019. https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/one-pagers/.

“Slavery in America.” Jim Crow Museum, 2024. https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/timeline/slavery.htm

“Socratic Seminar.” Facing History and Ourselves. Facing History, 2020. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/socratic-seminar.

“Step by Step Instructions.” Gallery Walks. Carleton College, May 7, 2018. https://serc.carleton.edu/introgeo/gallerywalk/step.html.

"The Future Of America's Past: Freedom's Fortress." 2019. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com/.

“Timeline - ReadWriteThink.” readwritethink.org. ILA/NCTE , 2020. http://www.readwritethink.org/parent-afterschool-resources/games-tools/timeline-a-30246.html#activity1.

“Very Important Meeting!/Our View.” Citizens for a Fort Monroe National Park, February 14, 2020. http://fortmonroecitizens.org/.

Wikimedia Commons. 2020. Timeline Icon. Image. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Timeline_(656040)_-_The_Noun_Project.svg#/media/File:Timeline_(656040)_-_The_Noun_Project.svg.