This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

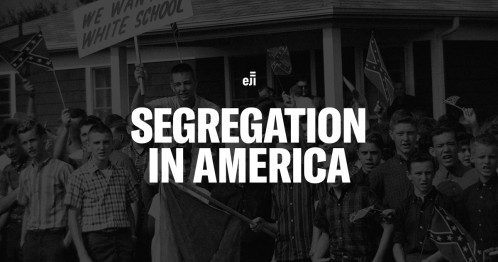

Confederate Monuments and History in Public Spaces

Read for Understanding:

The American Civil War ended in 1865, but most Confederate monuments were created many years after the Confederates’ surrender. Why is that? These learning resources explore the historical context behind these and other historical monuments as many Americans in recent years have changed their minds about issues related to Confederate iconography, and the broader topic of monuments and memorialization.

Key Vocabulary

Historical memory - the way that groups of people create and share narratives about historical figures or events

Iconography - the images and symbols associated with a person, a group, or a movement

Memorialize - to preserve the memory of; celebrate publicly

Monument - a statue or building created to retain the memory of a person or event and to tell a specific story

Public memory - the specific way that a group of people -- even a nation -- chooses to remember the past and the ways in which governments and citizens use these remembrances to inform the public

Public spaces - places that are open and accessible to people, including parks, public squares, and beaches

Engage:

What’s the difference between history and memory?

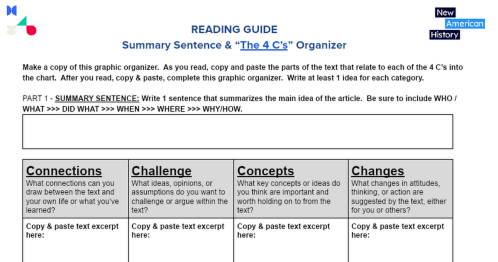

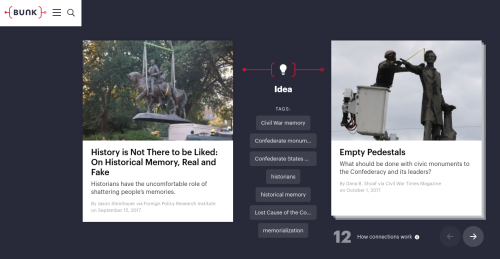

The 2015 killing of nine Black churchgoers by a white supremacist during a Bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina sparked a deep debate in America about Confederate monuments, flags, and other iconography, a debate that continues today. And the debate centers on questions of history and memory: What do these Confederate symbols mean, why do they still exist, and what do they tell us about the story that Americans tell about their history? In this task, read this Bunk excerpt, “History is not there to be liked”, written by historian Jason Steinhauer. Analyze his argument about the difference between history and memory. After you read, you will complete your copy of the graphic organizer, “Reading Guide”.

After you complete your organizer, click on this Bunk Connection to skim through other articles that share the theme of historical memory.

Then, share your ideas with a partner or with the whole class. Your teacher may use a collaborative tool like Google Docs or Google Slides to start the discussion. If working remotely, you may use breakout rooms through videoconferencing, or share via the collaborative documents suggested above.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

Why was Confederate iconography created?

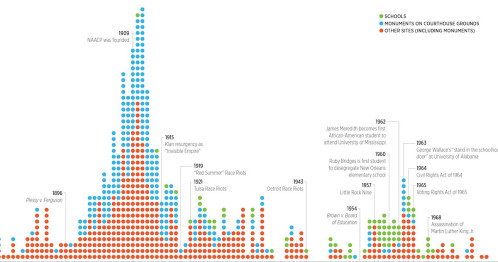

The American Civil War ended in 1865, but most Confederate monuments were created many years after the Confederates’ surrender. Why is that? This task asks you to examine the historical context behind the monuments using research from the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Equal Justice Initiative, and the American Civil War Museum’s “On Monument Avenue” online exhibit.

Read this Bunk excerpt to learn about the story behind the Southern Poverty Law Center’s study of Confederate iconography. Before you read, consider these questions as part of the “Take Note” Thinking Routine. As you read, don’t try to take notes, just read so that you are fully engaged in the speech:

- What is the most important point?

- What are you finding challenging, puzzling or difficult to understand?

- What question would you most like to discuss?

- What is something you found interesting?

After you read, answer one of the questions above individually. Then, turn to a partner and share your ideas. If working remotely, or using a device, you may answer using a collaborative tool such as a like Google Docs discussion board, or using a shared Google Slides deck.

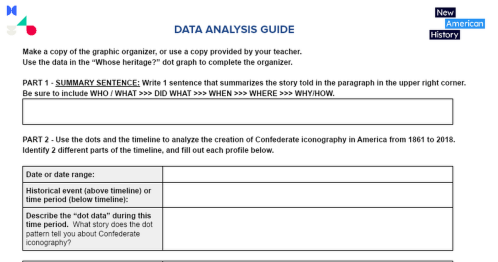

Next, examine this PDF dot map. Make note of the paragraph in the upper right, of the dot key, and of the different historical events outlined in the gray boxes below the timeline. Use your observation skills to analyze the data and to conduct your own research about it. To do that, complete Part 1 and Part 2 of the “Data Analysis” graphic organizer.

After you complete Part 2, use either the Equal Justice Initiative “Confederate Iconography” site or the American Civil War Museum’s “On Monument Avenue” online exhibit to answer your research question in Part 3.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

What can cause Americans to change their minds about Confederate monuments?

Fifty-one percent of Americans who responded to a 2020 NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll said they thought Confederate statues should be taken down, up from 35% in 2018, when the same question was asked. The poll points to the idea that current events and more complete historical research can cause people to change their minds about certain topics. In this task, you will examine two examples of Americans who changed their minds about issues related to Confederate iconography.

First, listen to this 11-minute segment of a Backstory podcast (“Seeds of Doubt”), in which a formerly staunch Confederate sympathizer and Civil War reenactor has a change of heart after examining his family history. After the interview part of the segment, historians Ed Ayers, Nathan Connolly, and Brian Balogh share their views.

Before you play the podcast, open your copy of the “Take Note” Thinking Routine and consider these questions. As the podcast is playing, don’t take notes so that you are fully engaged in the episode:

- What is the most important point?

- What are you finding challenging, puzzling or difficult to understand?

- What question would you most like to discuss?

- What is something you found interesting?

After reading through the questions, open a copy of your graphic organizer and play the podcast segment. When you finish listening, answer one of the Take Note questions on your graphic organizer. Also, answer Part 2 and the Exit Question.

If working remotely, or using a device, you may answer using a collaborative tool such as a Google Docs discussion board, or using a shared Google Slides deck. Your teacher will debrief by reading back student responses to the class and asking follow-up questions or by asking you to turn and talk to a partner to share your answers.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

Should we install public monuments for historical figures?

In recent years, public monuments to historical figures have ignited emotions and extreme actions. In one of the most extreme events, a woman in Charlottesville, Virginia was killed when a man attending a rally meant to protest the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue ran her over with his car. Are public monuments worth the strife? Should we remove all public memorials to historical figures to avoid the risk of violence, or does that erase something important? And who should decide who or what to honor with public statues? This task examines these questions and asks you to take a stand.

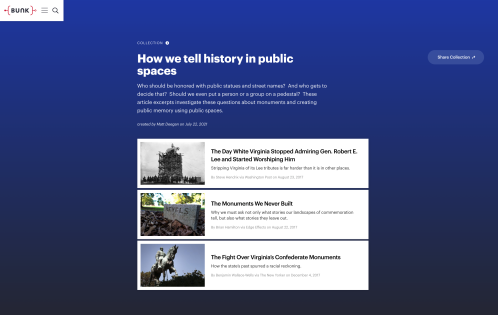

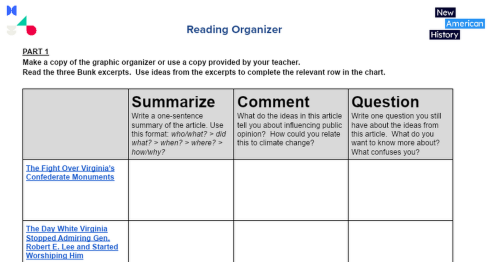

First, read these three excerpts in this Bunk Collection that investigate how we create public memory with public spaces, using Confederate monuments as a case-study example.

Make a copy of (or use a copy provided by your teacher), and complete this graphic organizer for each of the excerpts.

Then, analyze the benefits and drawbacks to public monuments by answering this summary question on page 2 of the organizer:

Should we install public monuments to historical figures?

Share your answer in Part 2 on a collaborative tool such as a Google Docs discussion board, or using a shared Google Slides deck. Your teacher will debrief by reading back student responses to the class and asking follow-up questions or by asking you to turn and talk to a partner to share your answers.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

What people, events, and ideas should we honor with public monuments and memorials?

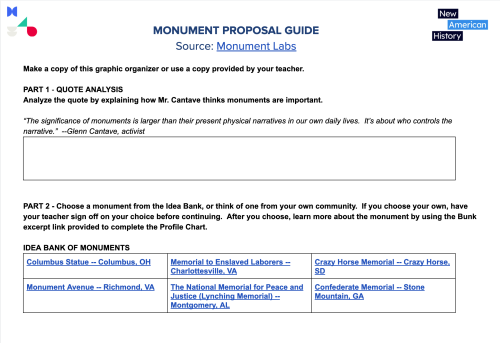

What people, events, and ideas are worth remembering and memorializing in public spaces? In this task, you will use a guide from the Monument Lab to reflect on this question and then design your own monument, for your own community.

Make a copy of this graphic organizer or use a copy provided by your teacher to organize your ideas throughout the task.

Analyze this quote:

“The significance of monuments is larger than their present physical narratives in our own daily lives. It’s about who controls the narrative.”

Choose a monument from the Idea Bank of Monuments, or choose one from your own community. If you choose your own, have your teacher sign off on your choice before continuing. After you choose, learn more about the monument by clicking on the links to the Bunk article excerpts to complete the Profile Chart. All articles are also in this Bunk Collection.

Brainstorm monument ideas for your own city or town. Create a proposal for your new monument.

Post a summary description of your proposal on a collaborative tool such as a Google Docs discussion board, or using a shared Google Slides deck. Your teacher will debrief by reading back student responses to the class and asking follow-up questions.

We’d love to see your ideas! Please ask your teacher or a trusted adult before sharing them with us via email at editor@newamericanhistory.org or share via social media (links on our pages) - we look forward to seeing them!

If you would like to extend your learning, consider hosting a community or school-wide screening of the film, "How the Monuments Came Down," in your own city or town. Reach out to us here for more information about the film and hosting your own virtual or in-person screening event.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

Eji. “Confederate Iconography in the 20th CENTURY: Equal Justice Initiative.” Confederate Iconography in the 20th Century | Equal Justice Initiative. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://segregationinamerica.eji.org/report/confederate-icongraphy.html.

Field Trip - Monument Lab. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://monumentlab.com/projects/field-trip.

“Jason Steinhauer.” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 24, 2020. https://www.fpri.org/contributor/jason-steinhauer/.

Lemon, Jason. “Majority of Americans Now Support Removing Confederate Statues, up 16 Points from 2018: Poll.” Newsweek. Newsweek, July 21, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/majority-americans-now-support-removing-confederate-statues-16-points-2018-poll-1519408.

“On Monument AVENUE.” The American Civil War Museum. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://onmonumentave.com/.

“Project Zero's Thinking Routine Toolbox.” PZ's Thinking Routines Toolbox | Project Zero. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://pz.harvard.edu/thinking-routines.

“Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy.” Southern Poverty Law Center. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://www.splcenter.org/whose-heritage.