This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Polio on Trial

Read for Understanding:

When the COVID-19 pandemic started it created a new challenge for scientists: to develop a vaccine that would help keep people from dying. Not long ago there was a race to produce another vaccine for an epidemic that was affecting children all over the world – polio. Learn about the disease and the progress of vaccinations then as a lesson for now.

Key Vocabulary

Epidemic - an outbreak of disease that spreads rapidly to many people in one area

Epidemiologist - Physicians, veterinarians, scientists, and other health professionals trained to examine how and where infectious diseases start and are transmitted to help control the spread and prevent future outbreaks.

Equity - the quality of being fair and reasonable

Eradicate - to do away with completely; wipeout

Herd immunity - when a high percentage of the community is immune to disease through vaccination

Iron Lung - a large metal chamber in which the body can be enclosed up to the neck, that maintains artificial respiration through alternating pulses of high and low pressure, used especially for polio victims

Medical or Clinical Trial - controlled experiments in which researchers test a new treatment in a group of volunteers. The tests help researchers determine how well the treatment works, the possible side effects, and the ideal dosage, among other factors

Paralysis - a loss of feeling in or the ability to move a body part caused by injury or disease of the nervous system

Polio (a short form of poliomyelitis) - a disease caused by a virus that attacks the spinal cord and damages the nervous system. Polio affects mainly children and can lead to paralysis or deformed limbs

Quarantine - a strictly enforced isolation to stop the spread of disease

Vaccine - a substance used to protect people and animals from very serious diseases. Vaccines contain germs of a particular disease--these germs have been killed or changed in a certain way in a laboratory to make them safe. A vaccine goes into a person's body in a shot that is given by a doctor or nurse. After a vaccine is put into a person's body, that person will not get that disease or will get only a mild case

Ventilator - a modern device for helping a person to breathe

Engage:

What lessons might we learn about vaccinations from the polio epidemic?

Most school-aged children are familiar with the term vaccination as all 50 states require some form of vaccination for students to enter public schools. As vaccinations for the COVID-19 pandemic are now available for students as young as 12, schools and parents continue to debate the pros and cons of vaccination. In the 1940s and 50s, parents faced similar challenges with the race for the polio vaccination. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “Introduction: Polio Strikes Fear in America.”)

Children like Gordon Kerby were treated for polio with the use of an Iron Lung. The Iron Lung was an early version of medical technology developed before the modern ventilator. Explore this Bunk connection, and meet Martha Lillard, one of the last of a generation of polio survivors who still depends on an iron lung to breathe, and learn more about how polio impacted children who were quarantined before a vaccine was discovered.

- How did the iron lung assist children stricken with polio?

- What surprised you about the story of Martha Lillard?

- How did the invention of the Candyland board game compare to your own quarantine experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic?

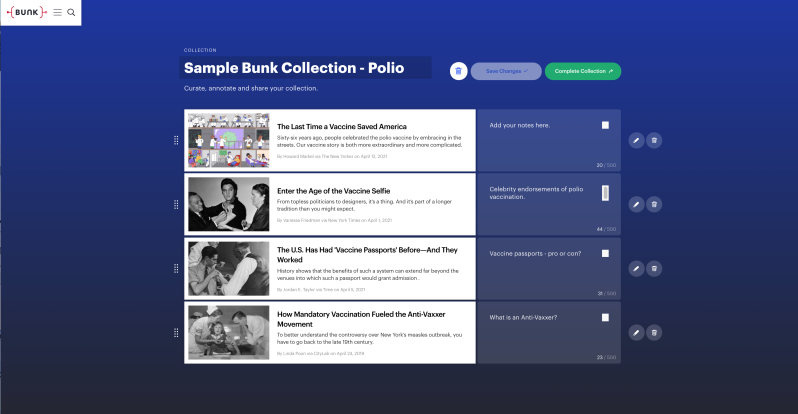

Take a few minutes to explore other Bunk connections, using the icons or tags related to each of the excerpts you read related to this episode of The Future of America’s Past.

Turn and talk to a neighbor and share another interesting connection you made using the “Share Connection” feature at the bottom of the screen.

If working remotely, your teacher may provide opportunities for you to work with a partner remotely, using video conferencing or a collaborative document such as Google Docs or Google Slides.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

How do immunizations impact public health for all citizens?

Polio took the lives of thousands of children and impacted millions of victims and their families worldwide. The search for a cure became a global effort amongst the scientific community, much like the challenges faced in more recent times for combating other modern-day public health crises like HIV-AIDS and COVID-19. (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “A Grand Experiment.”)

Clinical trials are an important part of the development of vaccines, and often require both government and private donations to fund the scientific research needed to find a cure for most medical diseases. Before Dr. Jonas Salk developed an effective vaccine for polio, Americans were surprised to learn President Franklin D. Roosevelt had developed polio as an adult. At the time, he was the first president living with a disability. While many would later criticize Roosevelt for attempting to downplay or hide his condition from the public, for fear of it impacting his political career, Roosevelt’s family was one of great privilege, affording him access to excellent health care and high-quality rehabilitation services. His funding to support rehabilitation and research was partially responsible for founding the Foundation which eventually led to Dr. Salk’s research and the development of the polio vaccine.

Take a few moments to read about President Roosevelt’s experiences as an adult polio survivor.

- How did his experiences contracting polio as an adult, and the social stigma of living with a disability influence his treatment and rehabilitation?

- In what ways did it influence his political career?

- How was the president able to use his wealth and privilege to help contribute to the funding of the polio vaccine?

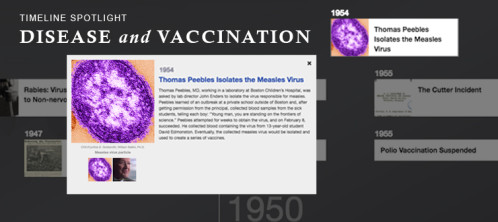

Now take some time to explore the History of Vaccines. You and your partner may choose to explore the Interactive Timeline or Herd Immunity animation.

Complete the following sentence stem using the information you learned in the video, from Bunk, and The History of Vaccines website. Add your thoughts on the vaccinations to this graphic organizer. Your teacher may allow you to compare your responses with a partner.

Your teacher may ask you to share your graphic organizer as an exit ticket.

Explain:

Can we ensure modern vaccines are distributed more equitably during a global pandemic?

For those with access to high-quality healthcare, treatment and recovery from life-threatening illness can at times be less severe. In the early days of the rollout of the polio vaccine, the initial rollout seemed a success. But as polio outbreaks persisted, not everyone was able to receive a vaccination right away. What was once thought to be a disease which was an “equalizer,” impacting children from all socioeconomic backgrounds, within a few years access to the vaccine presented barriers to those living in poverty, and people of color? (View video segment, The Future of America’s Past, “The Question of Equity.”)

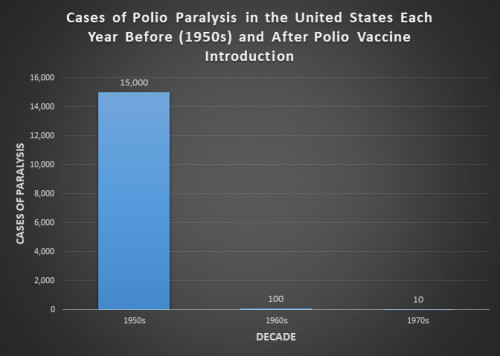

The United States did not wipe out polio overnight. It took over two decades once the vaccine was developed to reach herd immunity, particularly in communities of color and places without access to preventative medicine and universal healthcare. Even today, though no new cases of polio have originated in the United States, healthcare providers caution polio and other diseases are always dependent on careful monitoring and widespread vaccination distribution.

“I think it is a cautionary tale because it reminds us that a vaccine is, not a cure-all. A vaccine is as good as our systems to distribute it, use it, and use it consistently over time.”

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) and Smithsonian websites examine the history of polio vaccinations in the United States. Explore more about the history of polio and how the United States compares to other countries in terms of keeping polio under control through careful scientific monitoring and vaccination protocols.

- Use the CDC website to describe how communities in the United States have successfully prevented the spread of polio for the past few decades.

- Compare how widespread panic impacted American communities in the early months of the polio and COVID-19 pandemics. Use your own experiences to compare and contrast.

- Explore the Smithsonian website and explain the legacy of polio in terms of disability rights

- What role did technology play in the role of the treatment of polio and the development of assistive devices?

The video describes how communities of color were more severely affected by the delayed distribution of the polio vaccination to communities of color. President Roosevelt was criticized for providing segregated rehabilitation facilities for polio victims. White polio patients received excellent care for many years at his Warm Springs rehabilitation facility in Georgia. In 1941, a separate facility at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama was opened to treat Black polio victims with funding from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s charity organization.

When analyzing primary sources such as photographs, posters from the March of Dimes charity organization, or other artifacts, you must keep in mind that these images are created to convey a specific message or point of view.

Use the Smithsonian site and this analysis tool from the Library of Congress to examine one or more images from the online exhibit, Polio: Understanding Historical Photos. As you complete your analysis, think about the recent experiences you, your family, and people in your school or neighborhood have had as the COVID-19 vaccines became available for distribution.

This fillable form may be completed online and downloaded/saved as a .pdf file.

Your teacher may ask you to submit your answers as an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

What should parents and children know about vaccines to make an informed decision about becoming immunized?

In 2020, Americans living in poverty and those with preexisting medical conditions and lack of access to universal healthcare were impacted in greater numbers by the COVID-19 pandemic. Indigenous populations and communities of color were especially hard hit with higher mortality rates and prolonged hospitalization. As vaccines became available to combat the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, some Black Americans questioned the safety of vaccinations.

Historically, some Black Americans have been subjected to past abuses by the scientific and medical communities, including the Tuskegee Experiment and Eugenics. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some cited these past abuses as reasons for people of color to be hesitant to secure a vaccine, while others criticized this notion, citing more current distrust issues including the previous administration’s lack of confidence in science and early mishandling of the pandemic. All of these viewpoints may be explored by spending some time connecting these topics in Bunk. Save the resources you find most interesting as a Bunk Collection. You may also analyze COVID-19 vaccine data and public perceptions, including vaccination distribution by age, race, political affiliation, and location using the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor.

- Using the information you viewed or saved in your Bunk Collection or on the KFF site, what are some reasons people cite for not getting the vaccine?

- What patterns do you notice?

- What factors might one consider when deciding on taking the COVID-19 vaccine?

- How do some of this current thinking compare to the thinking of families in the 1950s-1970s when the polio vaccine was being developed and distributed?

To support and encourage Black families to participate in COVID-19 vaccinations, a group of Black scientists and medical professionals worked with the CDC to create this video as a public service announcement (PSA).

Using the Bunk Collection you created, and the CDC video, spend some time thinking and writing about your opinions on the topic of vaccinations in a Reflective Journal entry. Your teacher may provide you with a link to this graphic organizer to help you organize your thoughts. You will need to make a copy of it. Now that a vaccine has been approved for ages 12 and older, what are your thoughts about taking the COVID-19 vaccine?

Your teacher may ask you to record your thoughts in a private Reflective Journal instead of requiring an exit ticket.

Extend:

Do public service announcements and celebrity endorsements help combat public health crises?

When the polio epidemic was claiming the lives of and causing paralysis among thousands of American children and adults, organizations like Roosevelt’s charity, which eventually became known as the March of Dimes created public awareness campaigns. Some used monetized slogans, such as “For a dime a day…” to encourage donors at all levels to contribute. Children stricken with polio were used as “poster children” to tug at the heartstrings and encourage donations to fund research and rehabilitation efforts.

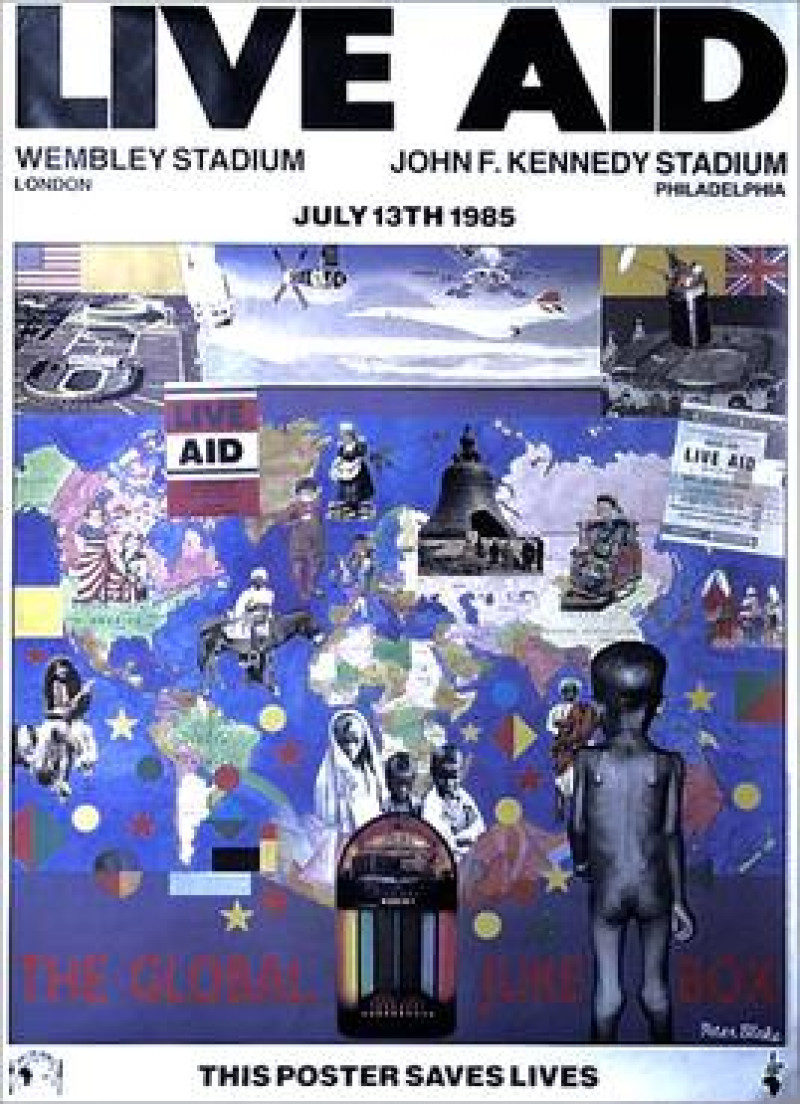

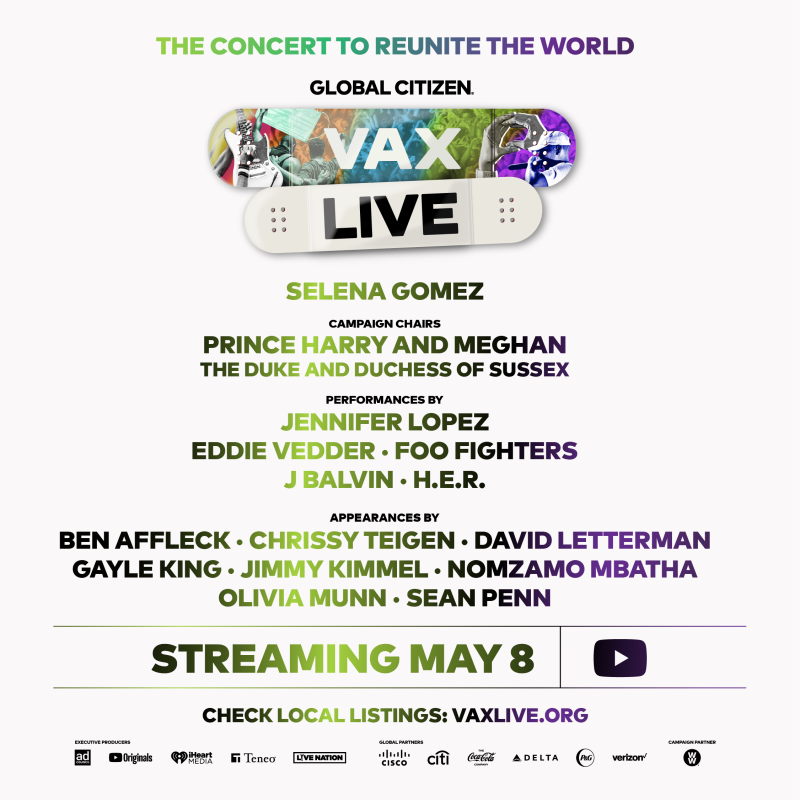

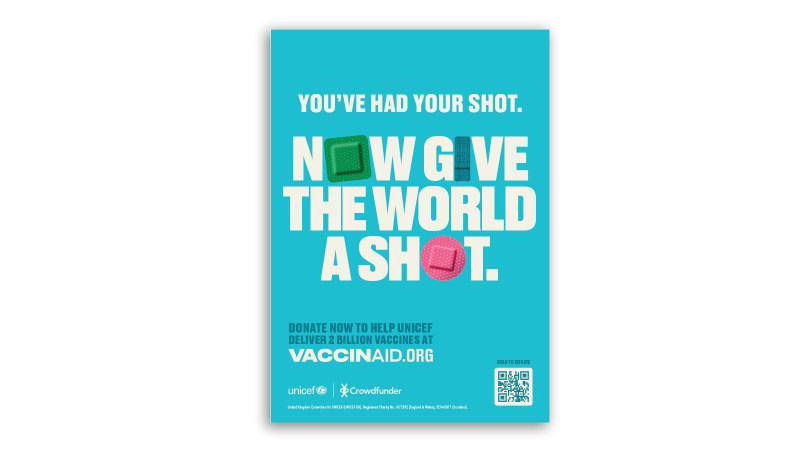

As television later began to replace the radio as the more influential form of mass media, telethons hosted by celebrities with call-in phone banks mixed in with short interviews with scientists, doctors, public health officials, and people living with debilitating medical conditions became the norm. In the 1980s, the United States joined efforts with several UK-based charities to end poverty, famine, and the homeless crisis. These include Comic Relief, now known for their Red Nose Day campaign, and Live Aid, which led to larger celebrity concerts supporting various charities or causes. With the later explosion of technology in the Information Age, Smartphones made donating to charities easier, and platforms such a FaceBook Live and YouTube brought live charity events into living rooms with interactive chats and donation features via texting, apps, and onscreen QR codes like never before. Examine these images of past public health campaigns supported by celebrities and their philanthropic work.

Much like the early March of Dimes campaigns in support of research and funding to find a vaccine for childhood illnesses like polio, celebrities continue to sponsor and endorse charitable causes via television and live-streamed events, such as the recent Vax Live event sponsored by the Global Citizen organization, raising awareness and funding to supply COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States and across the globe. Singer Dolly Parton funded research that led to the early clinical trials and approval of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

Even a group of former Presidents and First Ladies joined in these efforts, filming a PSA while receiving their vaccines.

Now it’s your turn! Create and share your own public service announcement video or original piece of Public Art in support of COVID-19 vaccines, (or another cause you support such as ending world hunger or an environmental-related charity.

To create a PSA, use a school-approved app such as SeeSaw, WeVideo, or FlipGrid.

Amplifier provides examples of Public Art created in support of public health initiatives such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and increasing awareness and access to vaccines for all Americans. You may draw, paint or create your own design using digital tools like Canva or Google Slides. You may also vote for your favorite piece on their website.

If your teacher or a trusted adult allows, you might share your video via YouTube or TikTok, or an image of your Public Art piece via social media (links on our pages). We would love to see what you created - you may also email us at editor@newamericanhistory.org - we might even feature your work in an upcoming edition of our newsletter! Be sure to tag us as you share!

Your teacher may ask you to submit your PSA or Public Art piece as an exit ticket or safely share it with the world.

Citations:

Ad Council. “Former Presidents and First Ladies 'It's Up To You”:60 | Ad Council and COVID Collaborative.” YouTube. Ad Council, March 11, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCza6UGmRTk.

“Archives.” FDR Presidential Library & Museum. FDR Presidential Library & Museum, 2021. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/archives.

Bell, W. Kamau. “Hello Black America! with W. Kamau Bell & Black Health Care Workers (4:58).” YouTube. YouTube, March 3, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qp6S4C6zG_M.

“Bunk Connection.” Bunk History. New American History, 2021. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/1702/connections?type=time&res=4680.

Chappell, Bill. “FDA OKs Pfizer COVID-19 Vaccine For 12-15 Age Group.” NPR. NPR, May 10, 2021.

Garcia, Alise, and Erik Skinner. States With Religious and Philosophical Exemptions From School Immunization Requirements, 2021.

“History of Vaccines - A Vaccine History Project of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia: History of Vaccines.” History of Vaccines - A Vaccine History Project of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia | History of Vaccines. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 2021. https://www.historyofvaccines.org/.

“I Used to Think... Now I Think...” Project Zero. Harvard University Graduate School of Education., 2015. https://pz.harvard.edu/resources/i-used-to-think-now-i-think.

“NMAH: Polio.” National Museum of American History | Polio. Smithsonian Institution, February 1, 2005. https://amhistory.si.edu/polio/index.htm.

Parton, Dolly. “Get You a Woman Who Can Do It All .” Twitter, January 21, 2020. https://twitter.com/DollyParton/status/1219681321762656256?s=20.

“Polio Elimination in the U.S.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 25, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/polio-us.html.

“Polio on Trial.” Bunk History. Field Studio, 2021. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/6974.

“Polio Vaccination in the U.S.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 6, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/vaccination.html.

“Primary Source Analysis Tool.” Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2021.

"The Future Of America's Past: Polio on Trial." 2020. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com/.