This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

School Interrupted

Read for Understanding:

We are often taught that change in society comes from action at the “top” - that is, from elected officials and legal challenges and more. But often overlooked are the activists who are at the beginning of a movement, campaigning for those changes. Many activists are students just like you. This lesson will introduce some of them.

This Learning Resource may be adapted by your teacher and used in whole or in part, for large group or individual learning situations. Some activities are designed to include working with partners, or participating in a group discussion. For remote learning, your teacher may adapt these directions based on your school's policies and access to technology.

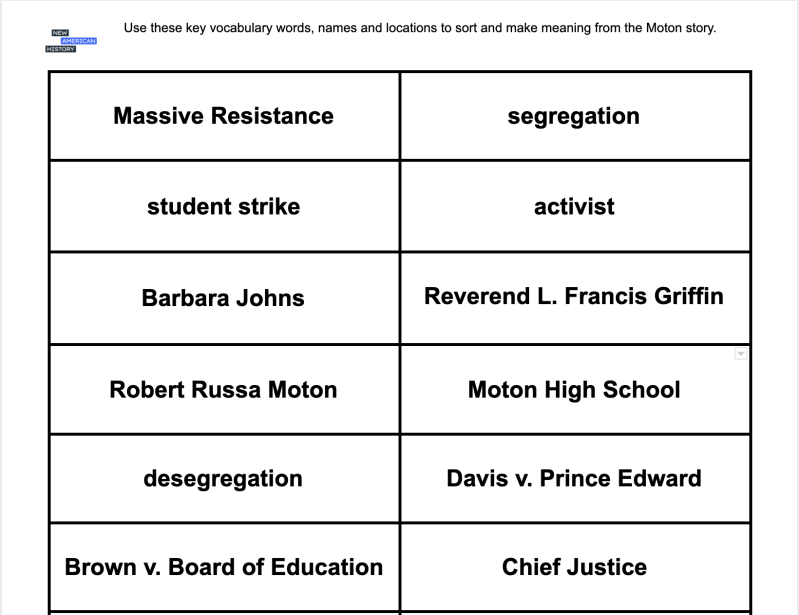

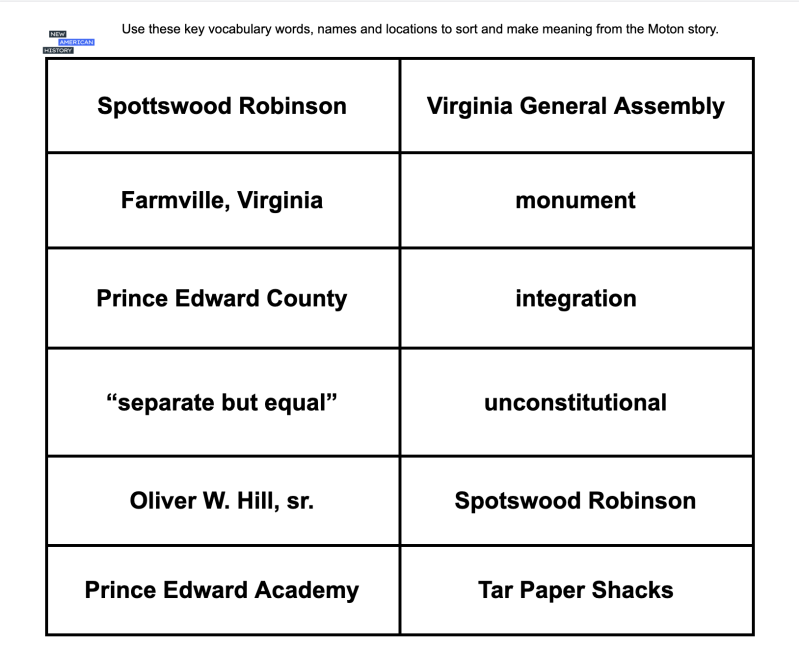

Key Vocabulary

Activist - a person who campaigns to bring about political or social change

Boycott - to stop buying or using the goods or services of a certain company or country as a protest

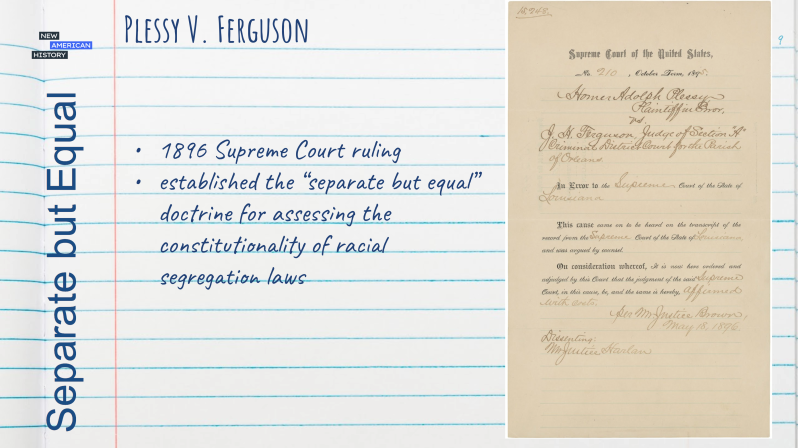

Constitutional - within the legal rights as described by this document which the United States government is based on; to go against it would be considered unconstitutional

Desegregate - the legal mandate to end segregation or racial separation

Integration - a social movement to make sure members of all racial groups experience fair and equal treatment in a desegregated community.

Locality - the neighborhood, community, region or area governed by a city, town or county form of local government. Examples: a capital city, county seat, or magisterial district.

Massive Resistance - a period of history in the late 1950s through the 1960s following the Supreme Court’s decision to make school segregation unlawful. During this time, some communities chose to shut down the public schools and refused to integrate.

Mobilize - to come together in an organized way to solve a problem, or respond to a crisis

Monument - a statue, plaque, building, work of art, or other honor created to memorialize or commemorate a person, place, or event.

Normalized - general acceptance of beliefs, policies, and systems rooted in injustice or prejudices as acceptable over time.

Segregation - the practice of race-based separation in public spaces including schools, public transportation, restroom facilities, and neighborhoods; many communities in the United States were segregated for centuries, and while the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s removed many legal barriers, some are still socially segregated

Segregation Academy - an all-white private school formed in response to school closings during Massive Resistance as a way to resist school integration

Social Justice - equal access to wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society

Strike / Walkout - a form of protest in which students or workers leave school or their jobs as a way to demand better treatment or equal rights. A similar form of protest is a Sit-In, in which people refuse to leave a public space until similar demands have been met

Engage:

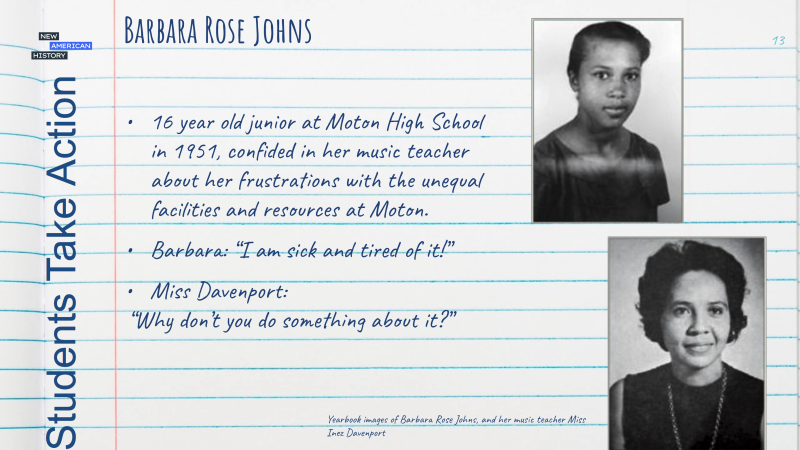

What role did teenagers like Barbara Johns play in desegregating schools in Virginia and the United States?

View this brief introductory video segment from The Future of America’s Past, “School Interrupted: Reaching for the Moon.”

After viewing the video, spend a few minutes sorting these key vocabulary words, including the names of people, places, and events. You may turn and talk to a partner, or work individually. Don’t try to match them like a definition. Instead, look for ways you might sort them into your own categories, or make connections to the video. If time permits, your teacher may allow you and a partner to compare your sorting strategy in small groups. There are no right or wrong answers, and you will have an opportunity to re-sort later!

In The Future of America’s Past, historian Ed Ayers visits places that define the most misunderstood parts of America’s past. In this segment, Ed visits the Moton Museum in Farmville, Virginia, and has a conversation with Joy Cabarrus Speakes about the legacy of the Moton School, now a historic civil rights landmark. (View video segment, "Barbara Johns' Grand Plan.")

Take a few minutes now to revisit your word sort, and feel free to move and remix your words based on what you have learned in this video segment. Discuss with your classmates why you did or did not adjust some of your categories or thinking based on the video.

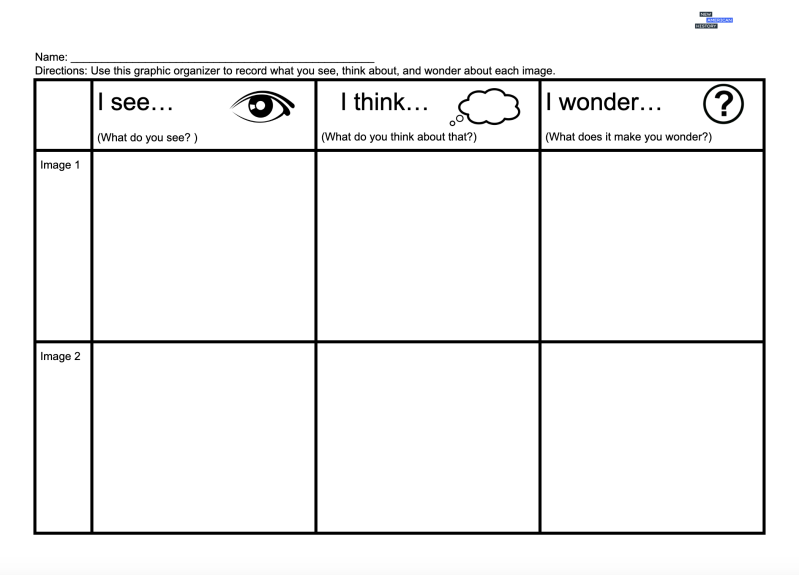

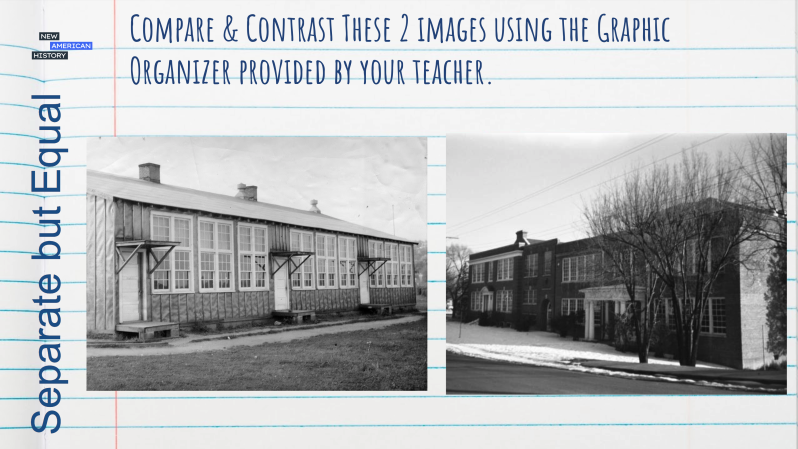

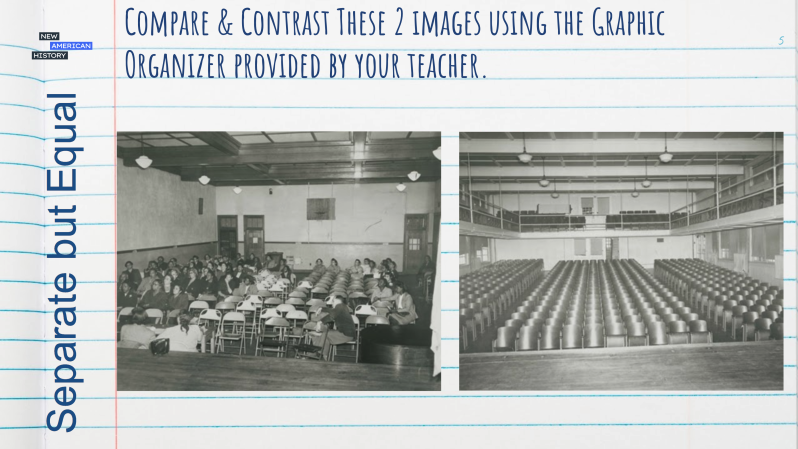

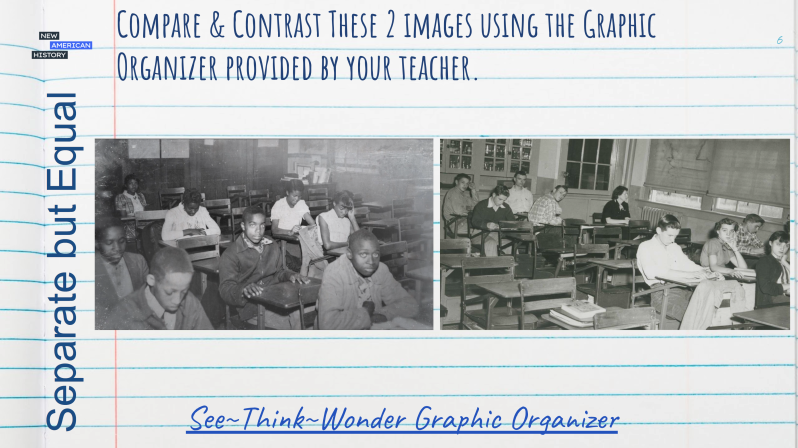

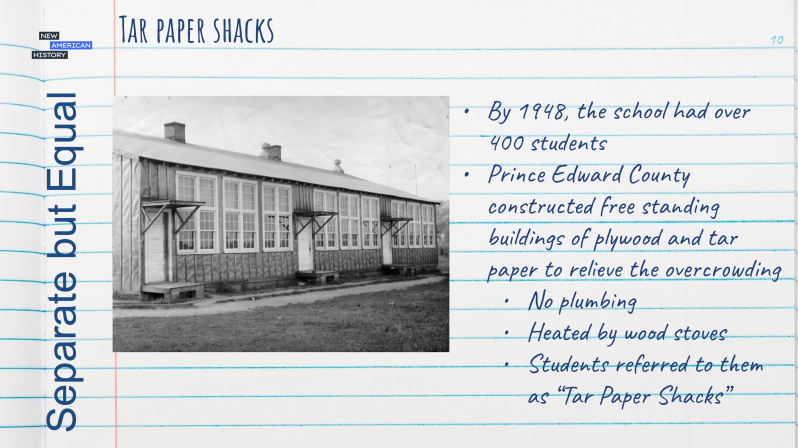

Next, spend some time examining these three sets of historic images from the Moton School and Farmville High School. You will use a See Think Wonder graphic organizer to help you observe, analyze, and reflect on the images.

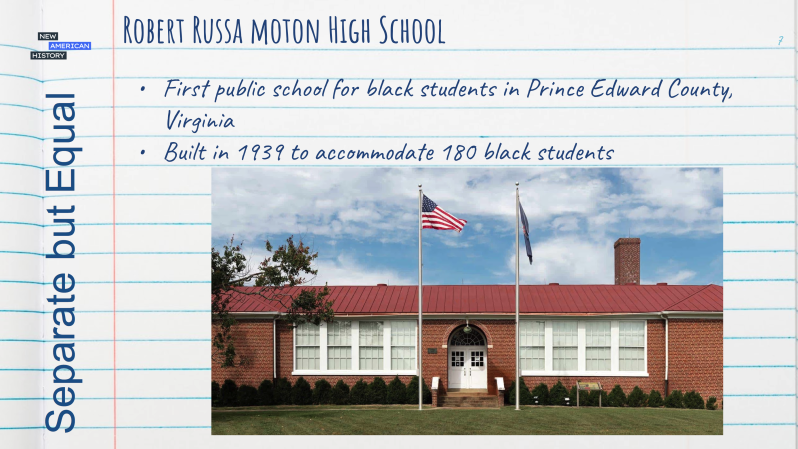

When you have completed your See Think Wonder analysis, take a few minutes to view these additional slides from the Moton School timeline. You may also rewatch the video segment as needed to build background knowledge.

- What new information do these images add to your understanding of the impact of Plessy v. Ferguson on segregated schools?

- Was “Separate but Equal” truly equal?

- Do you think Barbara Johns and her classmates were justified in their actions?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

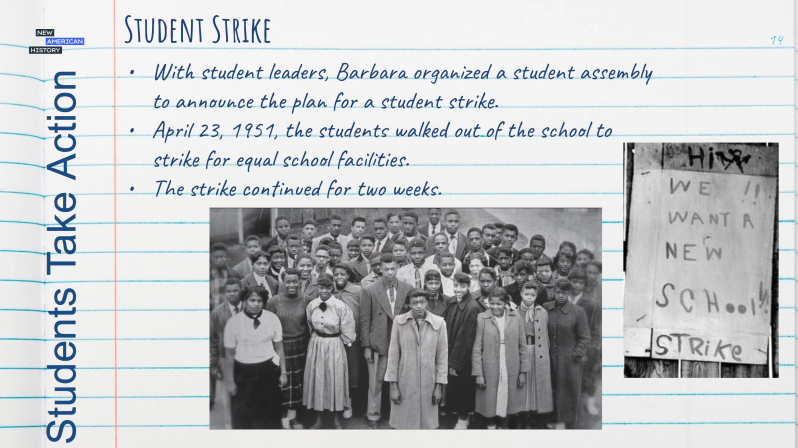

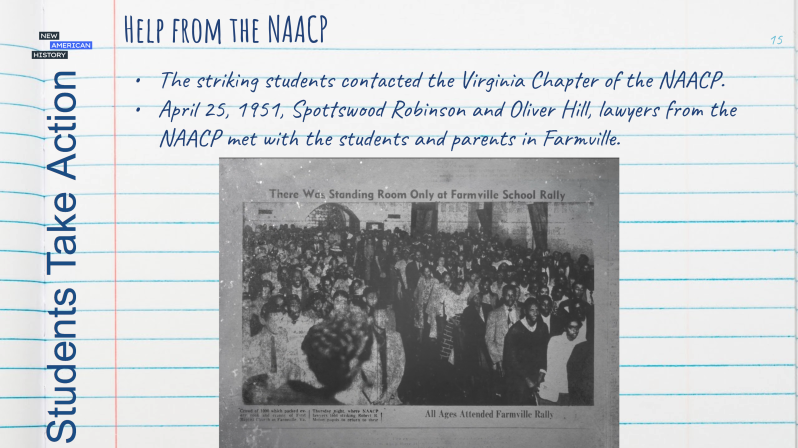

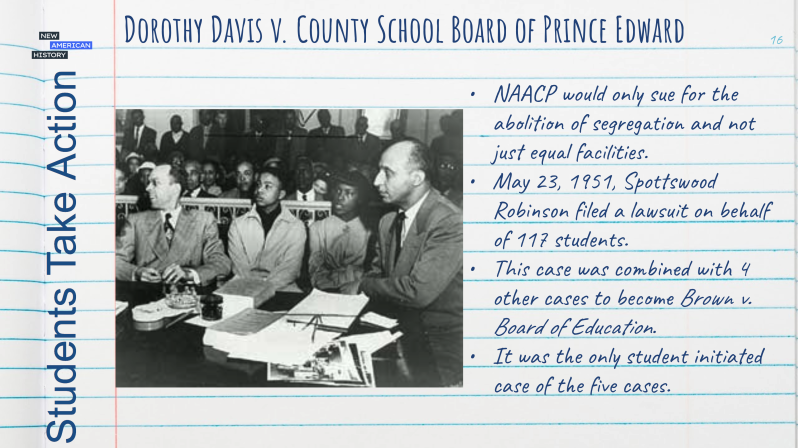

How did the Moton student strike mobilize the African American community in Prince Edward County to support efforts to end segregation in schools?

In this segment of The Future of America’s Past, historian Ed Ayers spoke with Reverend Samuel Williams, a classmate of Barbara Johns and now a faith-based community leader in Prince Edward County, Virginia. Reverend Williams describes his role in the student strike and the impact it had on the community. (View video segment, "Mobilizing the Community.")

- How did the Prince Edward County community react to the student strike at Moton High School?

- What role did a young Samuel Williams play in the student strike?

- Who became allies with the students?

- What barriers did they encounter?

View this quote from Reverend Williams:

“See, Barbara, she taught us how to combine vision with courage. There were people who would come and speak out against the movement, one or two, but we booed them down, right here and it was a great fire that was kindled.”

- What do you think Reverend Williams meant by the phrase “...combine vision with courage?”

- In your own words, share with a partner what you think Barbara’s vision was for the student strike.

- Repeat the same process for this phrase: “...it was a great fire that was kindled.”

- Give examples of how the Moton students kept that “fire” burning.

You may rewatch the video, or use the additional slides and images below to help guide your thinking and continue to build background knowledge.

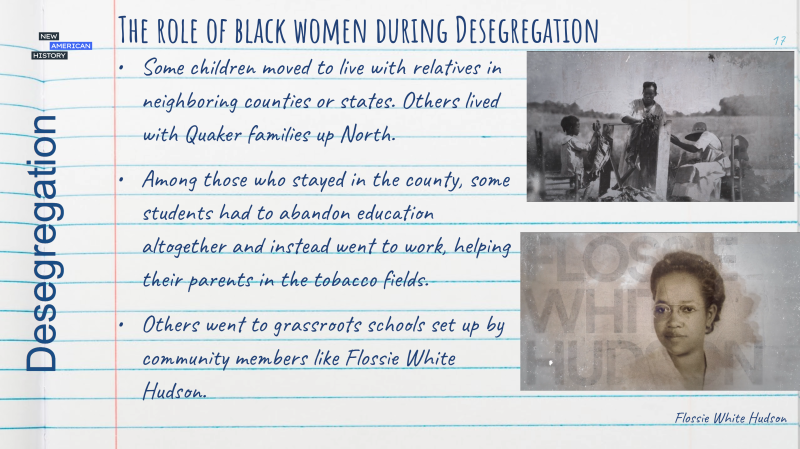

Reverend Williams’ church was not the only faith-based group to play a role in the events unfolding in Prince Edward County following the student strike. In this next segment, historian Ed Ayers meets with Amy Tillerson Brown, a historian who grew up in Prince Edward County. She explains how the student strike became part of a larger national movement to end segregation in schools. She describes the efforts of women in the African American community to continue to educate black children. (View video segment, “Schools Close, Black Women Take Action.”)

“You can take our public schools, but you can't stop us from teaching.”

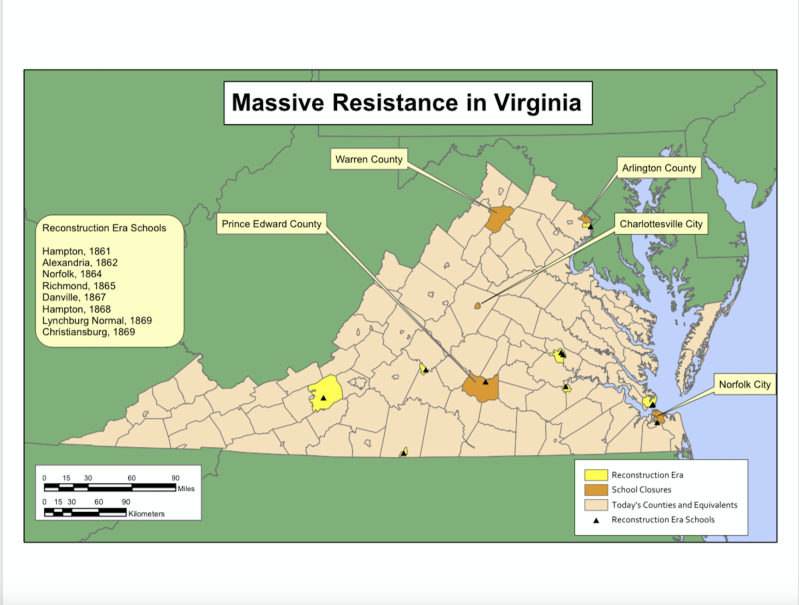

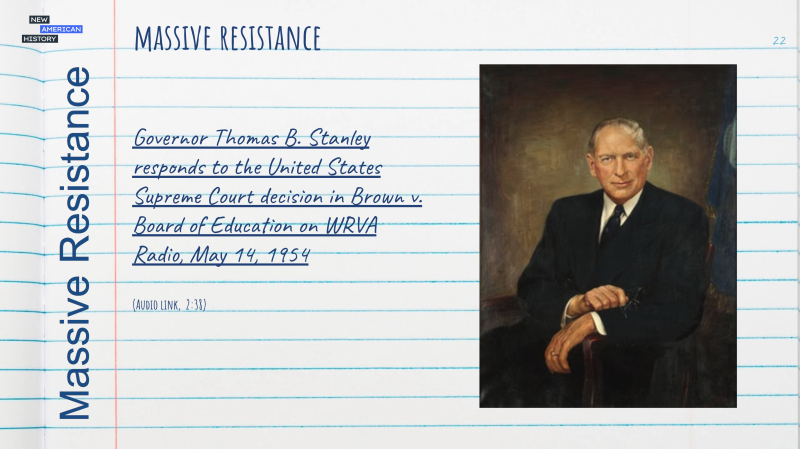

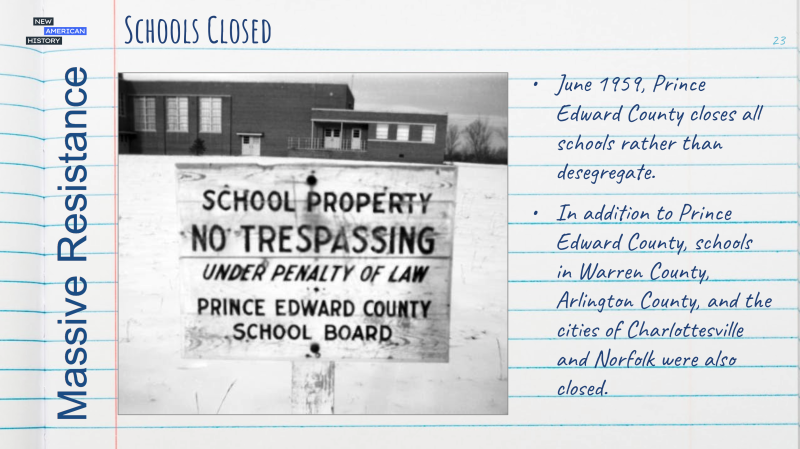

In this segment, historians Ed Ayers and Amy Tillerson-Brown explored the impact of closing the schools in Prince Edward County during the five year period known as Massive Resistance. Prince Edward County was not the only community in Virginia impacted by this decision. Read this excerpt from An Atlas of Virginia and examine the map.

- Using the atlas map, what do you notice about the location of the communities where schools were closed during the period of time known as Massive Resistance?

- Compare and contrast the locations of the Reconstruction era schools and the schools that closed during Massive Resistance. Do you notice any patterns?

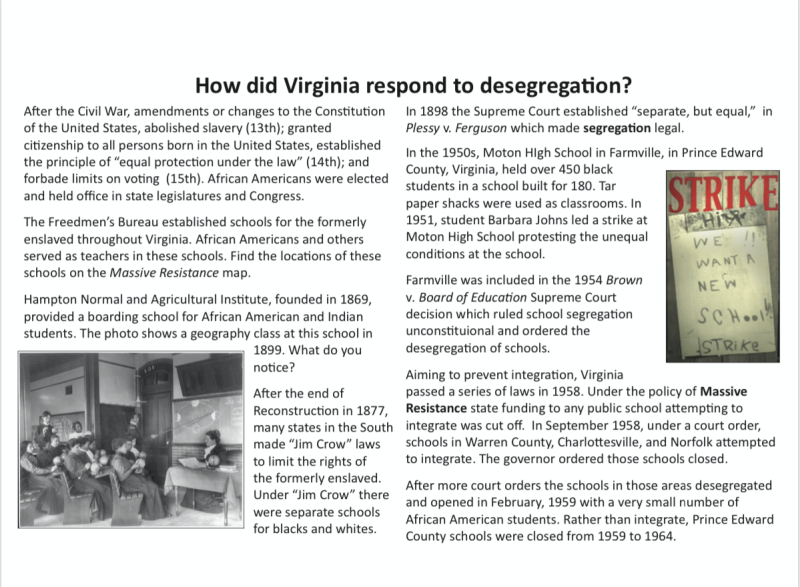

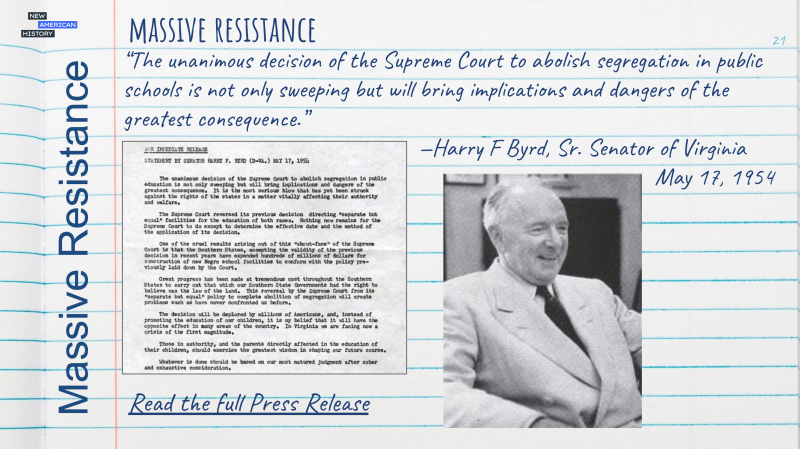

Review these key ideas and the reactions from lawyers and elected officials across the state, using the slides below to guide your thinking and build background knowledge.

- Thinking back to the video segment, the atlas reading, and the slides, what role did the legal system play in ending segregation in schools?

- Where might you look for more information about the school closings in Norfolk, Warren County and Charlottesville, Virginia? What did desegregation look like in other states beyond Virginia?

- How might you find out what happened to the schools in your community during this time period?

- Where might you look for information about desegregation in states beyond Virginia?

- Think about who was interviewed and mentioned in this segment of The Future of America’s Past: “Schools Close, Black Women Take Action.” How did they support or resist desegregation?

- What do you think is the difference between integration and desegregation?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

What role did white school officials and families in Prince Edward County, Virginia play during Massive Resistance?

African American communities were faced with difficult choices, including family separation, sending their children to work in tobacco fields, or attempting to create temporary schools. White parents responded by creating segregation academies, all-white schools supported in part by government funding. Prince Edward Academy was a segregation school built in Farmville in 1959 as part of white families’ support of Massive Resistance.

Today, teachers and school leaders across the United States are having discussions on how to best teach topics sometimes labeled “hard history,” including slavery and segregation. These are topics previously not openly or accurately discussed in many American history classes. Adults and younger generations who grew up after schools were integrated often do not have a clear understanding of these topics. Others lack basic knowledge of the hardships and sacrifices people made to ensure all students receive fair and equal treatment in schools, as well as in workplaces and in society. Historian Ed Ayers has spent many years studying, teaching, and writing about many of these topics. He spoke with Kristen Green, an author who grew up in Prince Edward County and whose family played a key role in establishing a segregation academy. They talked about the dark legacy she uncovered when she began to ask her own family questions about their past. (View segment, “A Segregation Academy and a Family Legacy.”)

Take some time to think about Kristen Green’s journey of discovery in researching her own family’s involvement in the creation of a segregation academy. She describes how schools like Prince Edward Academy normalized the policy of “separate but equal.” Use this quote from the video to write about your own views on how this period of history has been taught in the past, and the ways it is now being taught and discussed. Record your observations in a reflective journal. Reread your entry when you are finished, highlighting your top 2-3 ideas or opinions.

“Part of that moving forward, of becoming a place with a new identity, is acknowledging that history—that needs to happen by a lot of people, of the pain that was caused, before we can just move on.”

Your journal entry will then be used to participate in both small and large group discussions focusing on social justice issues past and present. You will use the Learn to Listen, Listen to Learn strategy. Your teacher will provide you with more specific instructions. If you are working remotely or enrolled in an online class, you may be able to use video conferencing with breakout rooms as your school permits. A shared Google doc could also be used to collaborate with classmates unable to join remotely at the same time.

The basic steps for this strategy are:

- Write about the topic in a student reflective journal, highlighting key points or words.

- Share your key points in a small group, and listen to the ideas shared by others.

- Actively listen and participate in a small group discussion once all group members have shared.

- Small groups present their key ideas to a larger group (full class or half of the class).

- Revisit your original entry in your reflective journal. Has your thinking shifted or strengthened about a topic? Take time to reflect on the small and larger group discussions.

- What did you learn from this activity?

- What questions do you still have?

- What did you learn more from—listening or presenting your own ideas? Explain your answer.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

In what ways do historic images help us uncover the untold human stories that helped shape American history?

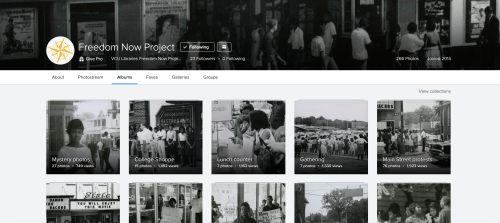

So much of the traditional way we have taught and learned about history focuses on memorizing names, dates, and events. These are often reinforced as we are reading a chapter in a textbook and answering questions, or memorizing certain facts to pass a test. In this segment of The Future of America's Past, historian Ed Ayers meets university librarian Alice Campbell, curator of the Virginia Commonwealth University’s Freedom Now project. Campbell’s work to preserve, identify and catalog historic images from the summer of 1963 helps us put human faces and local stories behind the headlines and history books. (View segment, “School Interrupted: Identifying the Strikers who Marched Farmville's Streets.”)

After viewing the video, take a few minutes to explore the rich resources preserved by Alice Campbell and the Freedom Now Project. You may want to use the See Think Wonder graphic organizer included in an earlier activity in this Learning Resource.

- How are the images in the Freedom Now Project organized?

- Which albums in the collection seem unfinished?

- What might explain the reason for the “mystery” images?

- How might the individuals in these images be identified?

- What type of data is collected on the site, and how might it be used?

The images preserved in the Freedom Now Project at Virginia Commonwealth University had been buried in a Sheriff’s department archive. Librarians rescued and preserved them for new generations of scholars and engaged citizens to learn about the events that unfolded during the summer of 1963 while schools remained closed in Prince Edward County. The images reveal how other townspeople and the news media responded to the boycott, and document the tension between law enforcement officials and protesters. Small details like the Back to School signs and March on Washington button help us think about both the importance of localized acts of civil disobedience in a small town. They also help us see how interconnected the Moton case was to the Civil Rights Movement.

Select 8-10 images from the Freedom Now project, the Google slide set, or other sites approved by your teacher. You will use these images to create a Virtual Tour of the events that took place in Prince Edward County, including the Moton student strike and the boycotts of 1963. Look for small details similar to the ones Alice Campbell pointed out to personalize your tour and make connections between everyday life and historic events. Many of the people in these images were later identified by Prince Edward County residents. You may choose to focus on one or two of these people and research the role they played in local history or their connection to the larger events. Look for the human side to these events, and use your tour to highlight the contributions of everyday citizens, particularly the students. Try to include images that illustrate this snapshot in time from multiple perspectives.

You may use a digital mapping platform like Google Tour Builder, HistoryPin or an ArcGISOnine StoryMap to create your tour, or a simple Google Slides presentation. You may work individually or in pairs/teams to create your tour—your teacher will give you more specific instructions based on your school’s approved technologies. Your teacher may also provide paper copies of selected images for students not able to access images digitally. Be sure to cite your scholarship based on your teacher’s directions. Your school librarian, like Alice Campbell, would be a great resource for this project!

Consider hosting a class, school, or community event to share your scholarship. The Rockingham County Public Schools in Virginia began with a similar project and later turned their tours into a place-based field experience. You may also use images from the previous slides or their website to build your tour. Be creative in how you tell these stories, and remember to focus on how you might use these images to help tell this story to someone who is not familiar with the Moton school strike or Massive Resistance.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers or plans for your tour on an exit ticket.

Extend:

How do we decide which stories are taught and learned in our schools?

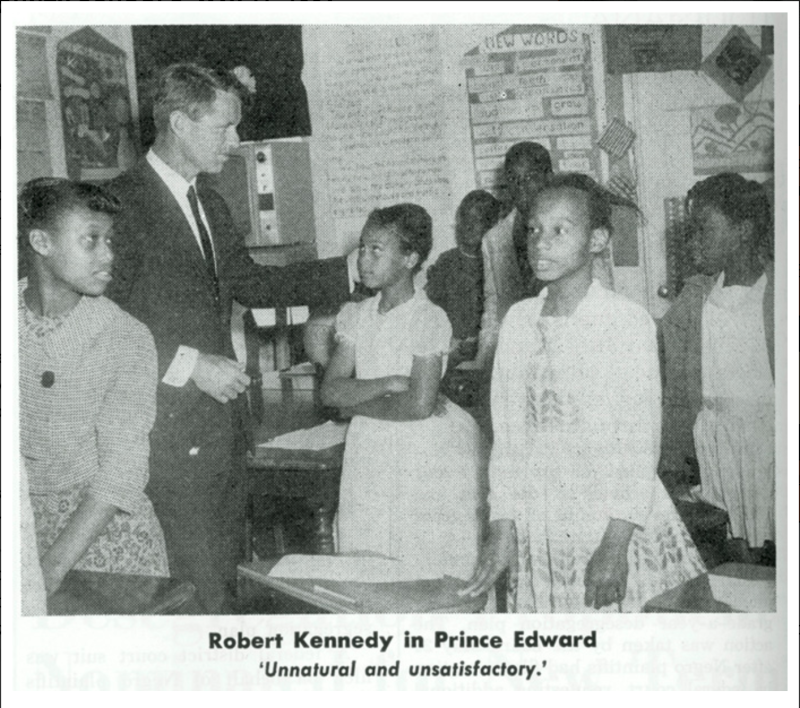

The students' demonstrations during the summer of 1963 brought more attention to the closed schools in Prince Edward County. President John F. Kennedy was under pressure from civil rights leaders and could no longer ignore that children in the United States were being denied a free public education. In 1963, the federal government helped open three “Free Schools” in Prince Edward County, renting back some of the closed schools to educate black children. They recruited teachers to move to Prince Edward County, and President Kennedy sent his brother Robert Kennedy, the Attorney General, to visit one of the schools.

“We may observe with much sadness and irony that, outside of Africa, south of the Sahara, where education is still a difficult challenge, the only places on earth known not to provide free public education are Communist China, North Vietnam, Sarawak, Singapore, British Honduras—and Prince Edward County, Virginia.”

In 1964, five years after the schools first closed, the Supreme Court, in a new decision, ruled against the school board officials who had closed the schools. Prince Edward County was forced to reopen its public schools to all children. Cainan Townsend grew up in Prince Edward County, graduated from Longwood University, and grew up hearing stories about how his own family was impacted by the closing of schools. Historian Ed Ayers met with him at the site of the original student walkout, the Moton School, now known as the Moton Museum. (View segment, “School Interrupted: Teaching the Next Generation of Activists.”)

In the video, Cainan Townsend discusses how the reopening of schools in Prince Edward County Schools in the fall of 1964 brought old and new challenges. Elected officials and segregationists within the community continued to underfund the public schools. Decades later, they even tried to block efforts to open a museum at Moton High School. Prince Edward Academy continued to operate as a private, all-white high school for many years before it was renamed the Fuqua School and its leaders tried to recruit a more diverse student body. Townsend also describes his own personal family connections: his aunts participated in the student strike led by Barbara Johns and his own father lost five years of his elementary school education.

Take a few minutes to review these final slides for more information about the end of Massive Resistance and the way people continue to honor the legacy of Barbara Johns and her classmates.

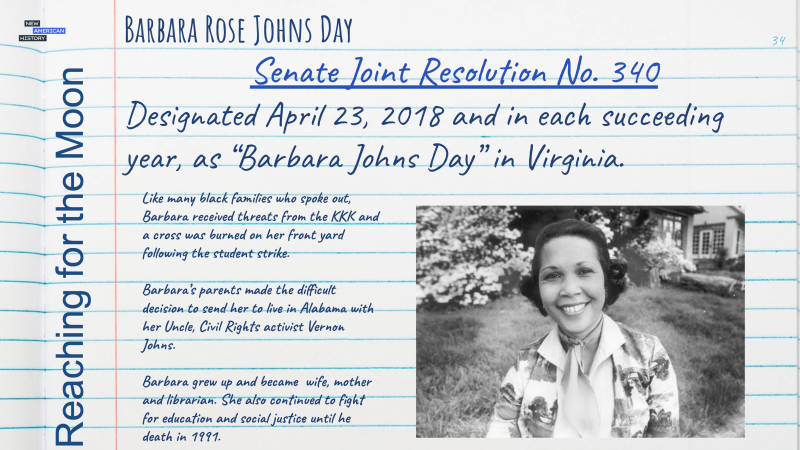

Today, the Moton Museum continues to educate the public about young people like Barbara Johns, a 16-year-old girl who took a stand for her beliefs long before adults like Rosa Parks gave up her seat on the bus, and before Dr. King gave the iconic “I Have a Dream Speech,” during the 1963 March on Washington.

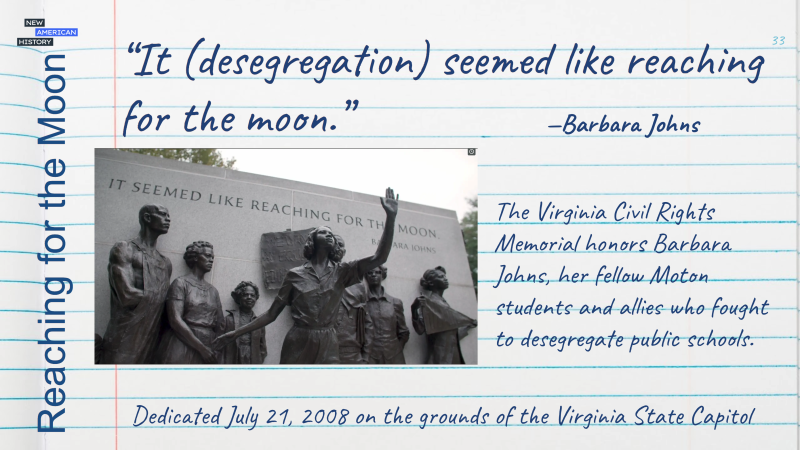

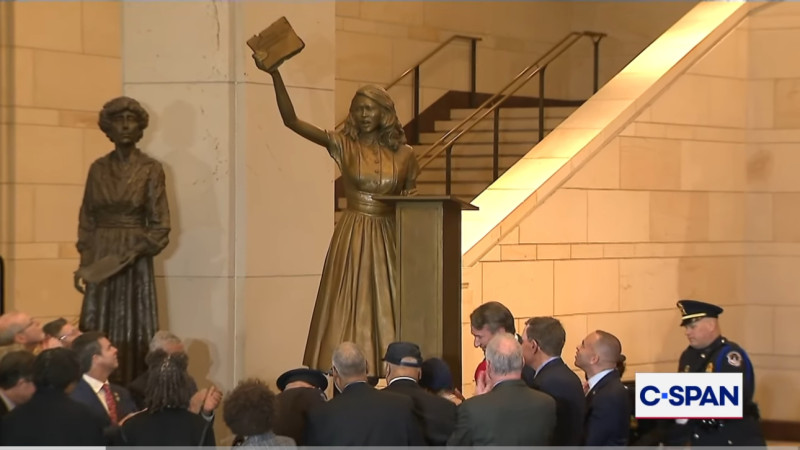

In 2008 The Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, a bronze and marble sculpture of Barbara Johns, was unveiled on the grounds of the Virginia State Capitol. The memorial commemorates the courageous 16-year-old at the front lines of the Moton High walkout. which helped bring about school desegregation in the state.

In 2020, The Commission for Historical Statues in the United States Capitol was charged with determining whether the Robert E. Lee statue in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the United States Capitol should be replaced (which it did recommend) and to recommend to the General Assembly as a replacement a statue of a prominent Virginia citizen to be commemorated in the National Statuary Hall Collection. After receiving numerous nominations from citizens of all ages, including many K12-teachers and students, the Commission approved a motion to recommend a statue of Barbara Rose Johns for the U.S. Capitol.

Robert Shetterly is an artist who created “Americans Who Tell The Truth.” Shetterly’s portraits honor citizens who courageously address issues of social, environmental, and economic fairness. By combining art and other media, Shetterly offers visual narratives to inspire a new generation of engaged Americans who “will act for the common good, our communities, and the Earth. Shetterly donated his portrait of Barbara Johns to the Moton Museum, where it now hangs in the same auditorium where, at the age of 16, she led the student strike in 1951 which would eventually help desegregate America’s public schools.

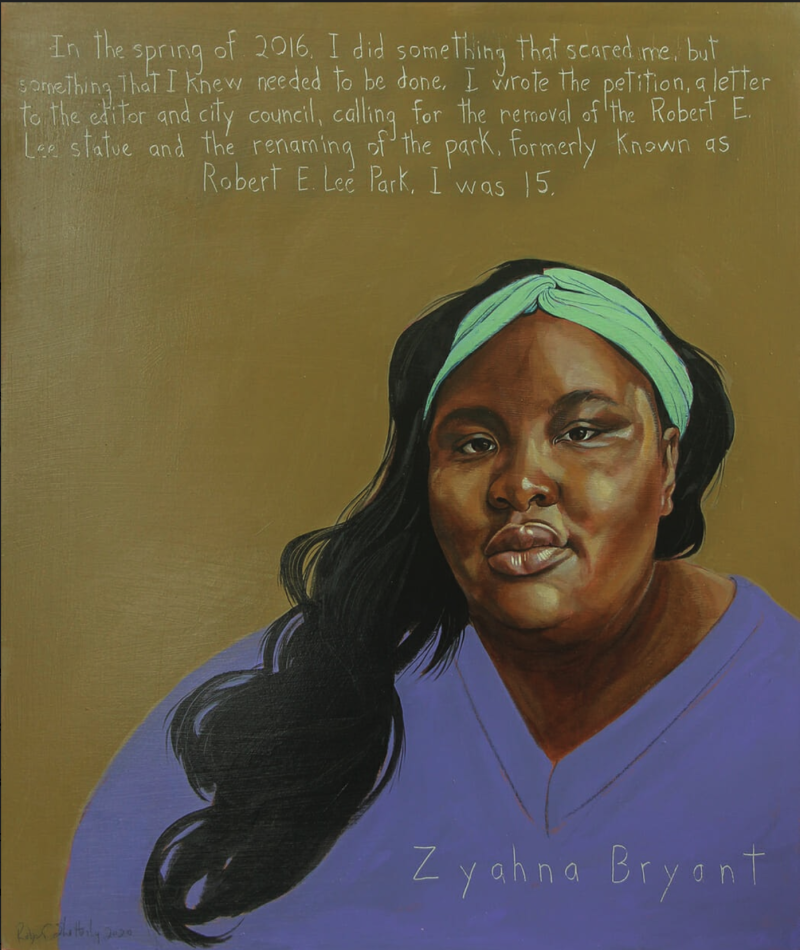

In 2020, Shetterly presented his latest student portrait at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center in Charlottesville, Virginia. Like Prince Edward County, the schools in Charlottesville were also closed during the period of Massive Resistance, along with schools in Norfolk and Warren County, Virginia. The Jefferson School, like Moton, honors the legacy of local civil rights activists who made a difference in their community.

Shetterly presented a portrait of Zyahna Bryant, who at the age of 12 organized her first protest march in response to the Trayvon Martin verdict, and at age 15 wrote a letter to her local city council demanding they remove a Confederate monument of Robert E. Lee and rename the local park where it stood. Inspired by Barbara Johns, and other young activists who “speak the truth,” Bryant hopes her actions will also inspire future community organizers, activists, and leaders. “If we don’t have people who are standing their ground and continuing to seek truth in this fight for justice, then people like me who are young, black, female will continue to be marginalized in their own efforts,” said Bryant.

Take some time to review the other portraits, especially those of young activists, featured in Americans Who Tell The Truth. Think about the people in your own schools or community who, like Barbara Johns and Zyahna Bryant, have made an impact on their communities. Select someone to nominate for a future portrait, or perhaps describe your own solutions to a local community concern. You will create a portrait or write a narrative similar to the ones featured on Robert Shetterly’s website. You may choose to work alone, or with a partner. You may use a free digital portrait app like Insta Toon, a website like Dreamscope, or create an original drawing, painting, sketch or photograph of your nominee.

Your teacher may choose to display your work in a virtual gallery using Google Slides or your school’s LMS, such as Canvas or Blackboard, or create a school or community display. Here is a link to the exhibits of Shetterly’s work and the student-created portraits displayed in Charlottesville. Our friends at Americans Who Tell the Truth would love to see your work, too. Your teacher may contact them about opportunities to share your ideas and creative work.

In 2025, while still studying for a Master's Degree at the University of Virginia, Zyahna Bryant was elected to the Charlottesville City School Board. Later that same year, a statue of Barbara Rose Johns was placed in the United States Capitol's Statuary Hall, replacing the one of Robert E. Lee, which had been removed earlier.

Your teacher may ask you to begin to record your ideas for a new portrait and narrative on an exit ticket.

Citations

Campbell, Alice, ed. “Freedom Now Project.” VCU Libraries. VCU Special Collections and Archives, 2014. https://www.library.vcu.edu/research/special-collections/exhibits/freedom-now/.

Dickenson, Beau. “Farmville Tour Guides.” Farmville Tour Guides. Rockingham County Public Schools, 2019. http://farmvilletourguides.rockingham.k12.va.us/.

Edward H. Peeples. "Prince Edward County (Va.) Public Schools.” Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries Digital Collections, digital.library.vcu.edu/digital/collection/pec.

Heinemann, Ronald L. "Moton School Strike and Prince Edward County School Closings." Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 21 Jan. 2014. https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/moton_school_strike_and_prince_edward_county_school_closings.

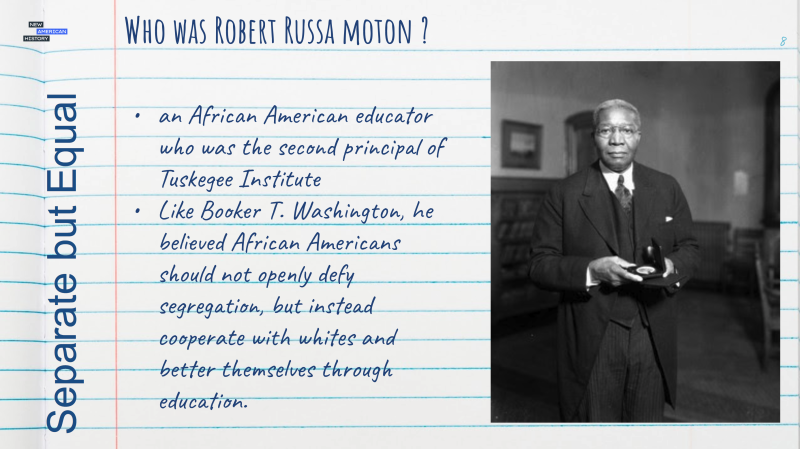

Moton Museum. The Robert Russa Moton Museum, 2020. https://www.motonmuseum.org/learn/.

“Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, 25 May 2018, www.archives.gov/education/lessons/davis-case.

“The Prince Edward Case and the Brown Decision.” Brown V. Board of Education: Virginia Responds, The Library of Virginia, www.lva.virginia.gov/exhibits/brown/decision.htm.

Robert Shetterly. “Robert Shetterly's Americans Who Tell The Truth.” Home | Americans Who Tell The Truth, 2020. https://www.americanswhotellthetruth.org

"The Future Of America's Past: School Interrupted." 2020. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com/.

Thomas, William G. Television News of the Civil Rights Era 1950-1970, Virginia Center for Digital History: University of Virginia, 2005, www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/civilrightstv/index.html.

“Visible Thinking - See Think Wonder.” Visible Thinking | Project Zero. Harvard University, February 24, 2020. https://pz.harvard.edu/projects/visible-thinking.