This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

The Revolutions

Read for Understanding

What does “freedom” mean to those outside the halls of power — and what did it mean during the American Revolution? We explore Boston and Philadelphia to put that question to curators, museum educators, a playwright, and a tribal preservation officer. Learn about the ways in which women, Native Americans, and African Americans made the words of the Revolution come true in their lives.

Key Vocabulary

Arbitrary - not planned or chosen for a particular reason, random

Arms - weapons, such as guns or rifles

BIPOC - acronym used as a more inclusive way to refer to Black, Indigenous, and people of color (non-white).

Colony / colonize - an area that is controlled by or belongs to a country that is usually not geographically connected; to take control of an area, usually by force, and send people to live there, often displacing the native inhabitants.

Covenant - a formal and serious agreement, contract, or promise

Demographic - the study of human population using data such as age, race, gender, income, education, religion, occupation, and other categories.

Emancipate - to free (someone) from someone else's control or power, such as an enslaved person or minor child.

Empire - a group of countries, territories, or regions that are controlled by one ruler or one government; in business a group of smaller businesses under the control of one person or larger business/company.

Feminist - a person who believes men and women should have equal rights and opportunities, including wages, legal rights, and property ownership

Foment - to cause or try to cause the growth or development of a rebellion, war, revolution, or violent uprising

Historical Empathy - understanding how people from the past thought, felt, made decisions.

Inherent - existing as a natural and permanent quality of something or someone else

Levers of Power - people in positions of economic or governmental power and privilege, or organizations, institutions, and technologies that can enable us to strengthen the impact of our voices and our actions

Material Culture - the physical objects people create and use in daily life (ex. artifacts, clothing, food, buildings, documents, tools, and technology)

Parliament - legislative body, mostly in Europe or countries formerly under European rule, most notably in France and the United Kingdom.

Pension - a regular payment made during a person's retirement from the government or a company the employee contributed to during their working life

Place-based - information based in part as it relates to a geographic location

Repatriate - to bring or send back, including people (ex. prisoners of war, human remains of fallen soldiers), or objects (ex. artifacts, art or other cultural assets) to their country of origin.

Revolution - A forceful attempt by many people to end the rule of one government and start a new one; the sudden, extreme, or complete change in the way people live, work or govern, often resolved by war.

Settlers - groups of people who move to live in a new country or area

Settler colonialism - refers to displacing or forcing out the native populations of a region or territory.

Sovereignty - a country's independent authority and the right to govern itself

Topography-the study of shape and features on the surface of the Earth

Wainscoting - decorative wooden paneling covering the lower part of the walls of a room.

Wampum - beads made from shells used by indigenous peoples of North America for ornamental or ceremonial use. Wampum had value as a trade item between Native peoples before European contact, and later after European settlement of America, wampum became currency as well as to signify social, economic, political, and religious covenants.

Engage:

What did freedom mean for people who needed it most?

If you pick up almost any American history textbook, the index includes lists of names, dates, and places. Many pages include maps of colonial-era cities like Boston and Philadelphia, stories of the “Founding Fathers,” or annotated copies of “Famous Documents.” Others include whole chapters on Revolutionary War battles, images of war heroes, and patriotic symbols. Few textbooks include the stories of all Americans who helped shape this nation’s history. For this reason, it is up to historians, documentary filmmakers, historical fiction writers, and teachers to help fill in those missing pieces in the story of America. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "What Freedom Means.")

Brainstorm a list of questions about the video. Use these “question starts” to help you think of interesting questions if you get stuck:

Why...?

What are the reasons...?

What if...?

What is the purpose of...?

How would it be different if?

Suppose that...?

What if we knew...?

What would change if...?

Review the brainstormed list and draw a star (or use a star ⭐ emoji) next to the questions that seem most interesting.

Select one or more of the starred questions to discuss for a few moments. If you are learning in a classroom with your teacher and classmates, Turn and Talk to an elbow partner. If working remotely, your teacher may ask you to use a collaborative tool such as Google Slides, or chatbox for video conferencing.

Reflect: What new ideas do you have about the American Revolution that you didn’t have before?

“Traces of the founding fathers are easy to find. Less clear is what the Revolution meant for those outside the halls of power. What did freedom mean for people who needed it most?”

In the video, historian Ed Ayers asks: “What did freedom mean for people who needed it most?”

- Which people do you think he meant when he mentioned the “...people who needed it most?”

- Where might you search for a resource to support your answer?

- What evidence could you use to support your answer?

To further our understanding of the past, we often turn to museums and historic sites to interpret the past and help us make connections to the present. When trying to understand how people lived, the decisions they made, and how their ideas about what is fair and right so long ago might differ from what we believe today, sometimes it is helpful to visit the places where history happened. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Many Revolutions.”)

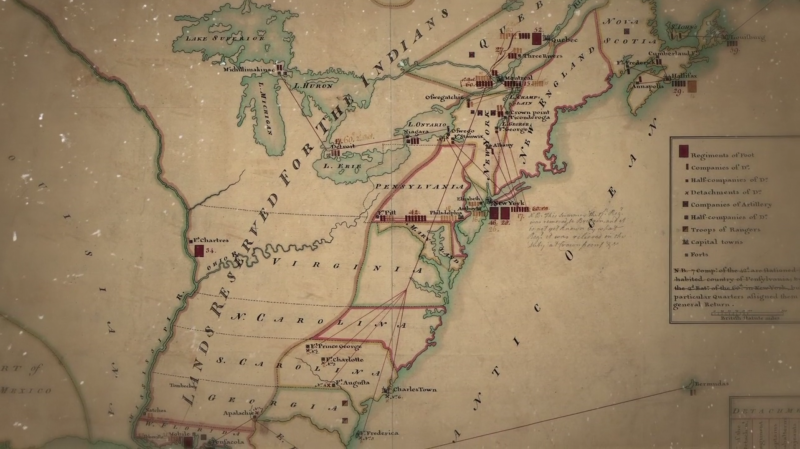

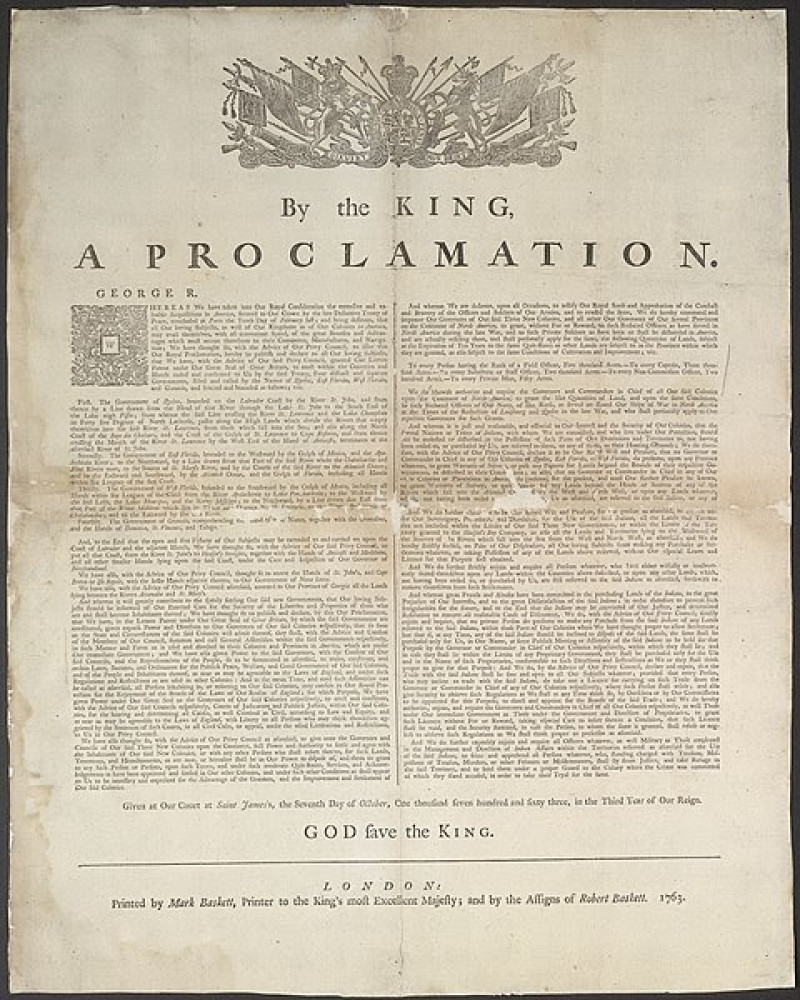

Study the map of “His Majesty’s forces in North America” and the image of the original Proclamation document. Our friends at the Avalon Project at Yale provided the transcript here. (You may work in pairs, either with an elbow partner or if working remotely, on a collaborative document as your teacher permits.)

- What do you notice first about the map?

- What questions do you have about the map?

- Consider the settlement patterns you see on the map-how would you describe features of the topography where the greatest number of people lived and worked?

- What promises are made on the map?

- Do you see promises in the language of the Proclamation document?

- Are there any statements in the Proclamation document that agree or disagree with the text you viewed on the map?

- Whose interests are best served, according to the map and document?

- Who is likely to support the King’s decision?

- Whose voices are not heard in either the document or the map?

Old English settlers (colonists) expected their Parliament and their new King, George III, to keep certain promises made in the war to build an empire in North America. Indigenous populations were also seeking promises to be kept.

- How did the King solve these demands to keep all these promises?

- What choices did the King make, and what did he or others have to give up to keep those promises?

- Whose promises were kept, and at what cost?

- Whose rights were being protected?

- Consider again, “What did freedom mean for people who needed it most?”

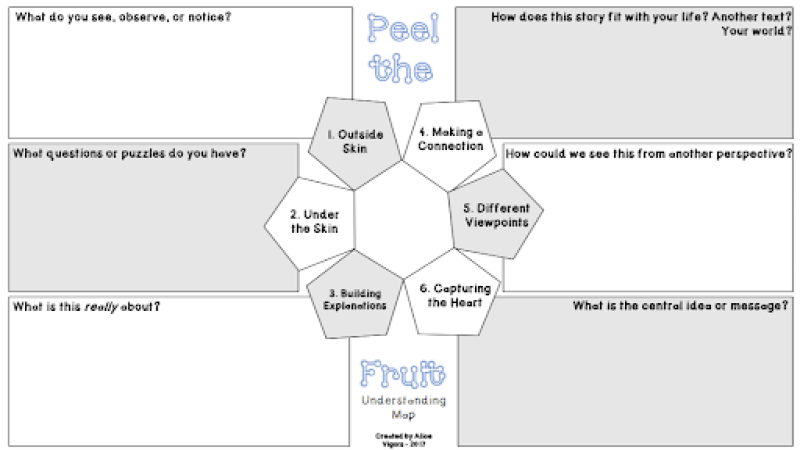

Summarize your thoughts on these questions by completing the Peel the Fruit graphic organizer, using the content from the videos, the map, and the Proclamation of 1764 document.

In the video, Darren Bonaparte shares an important piece of material culture with host Ed Ayers. The Wolf Belt is believed to be an example of the covenant chain of peace and friendship between Great Britain and the Iroquois people. Bonaparte writes more about Wampum here, explaining its meaning and value to the Mohawk people. (Image courtesy of The Future of America’s Past.)

Repatriation, or the returning of material culture to the people or country of origin, including artifacts, important historical documents and priceless works of art such as the Wolf Belt, have brought into question the ethical purposes and practices of museums across the globe. In recent years museums and governments have seen growing support from donors and patrons to rethink the origins of permanent collections, and the way exhibits are curated. Virtual museum exhibits, and sites like Google Arts and Culture, increased in popularity as access to technology increases and 3-D imagery continues to improve the user experience.

Take a few minutes to explore this Bunk Connection. Turn and talk to an elbow partner, or if working remotely, your teacher may give you access to a breakout room via video conferencing, or a collaborative doc such as Google Slides to share your thoughts on the repatriation of material culture.

Repatriation is not limited to material culture. Indigenous lands seized during the colonial era and by later generations have a complicated history tied to numerous treaties and policies granting state and/or local recognitions spanning multiple centuries and nations. In response to these ongoing conversations, many public gatherings now begin with a simple land acknowledgment statement while some communities are having discussions about returning public lands, such as state or national parks back to indigenous peoples such as the Mohawk.

In the video, Darren Bonaparte discusses the loss of ancestral lands and his peoples’ relocation into Canada. Many Mohawk living along the western frontier supported the British hoping to protect their homelands from further occupation by American settlers. After the Revolution, the British left, retreating up north to their colonial settlements in Canada, leaving the Mohawk people surrounded by American settlers. For the Mohawk, this was the beginning of the end for them in New York state. Losing their homeland included losing the graves of their ancestors, as most relocated north to Canada, too.

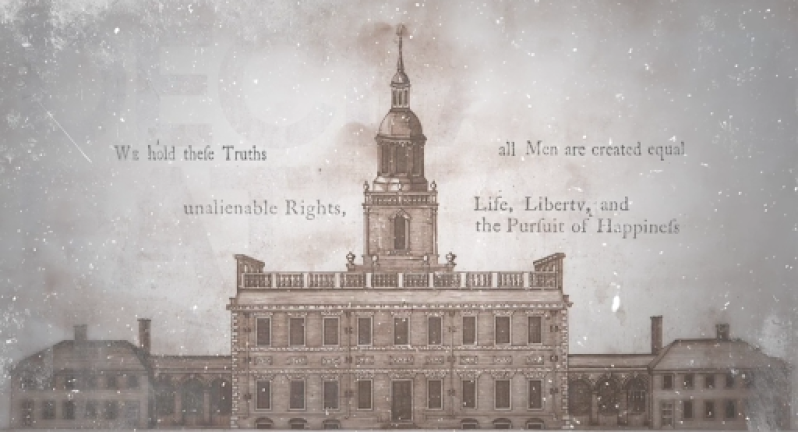

“We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

This quote is from the opening section of the Declaration of Independence. Explore another Bunk Connection between this episode of The Future of America’s Past and this excerpt from the end of the Declaration of Independence.

Notice the tags connecting the episode’s content and the excerpt. View some of the other connections to the episode. Turn and talk to an elbow partner, or if working remotely your teacher may provide access to a breakout room in a video conferencing platform or a collaborative document such as Google Slides.

- Paraphrase the term unalienable rights as you discuss the connections with your elbow partner. How did the grievances you read about in the Bunk excerpt compare to the Founders’ earlier statements on “...all Men are created equal?”

- How do the statement and the concept of unalienable rights apply to BIPOC then and now?

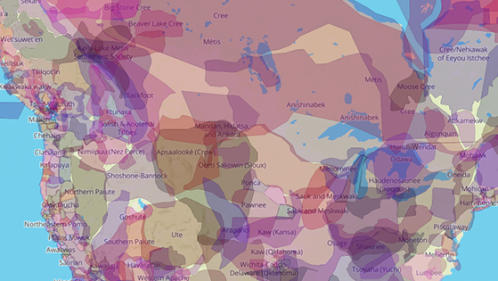

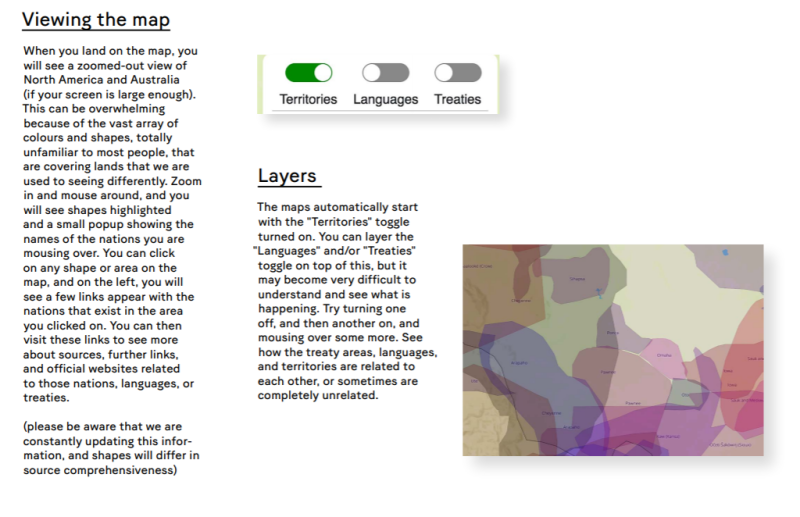

This crowdsourced map, created by Native Lands Digital, is an indigenous-led project mapping the territories, languages, and treaties of Native Americans across the Americas, Australia, and beyond. Take a few minutes to explore the map online.

- Use the search box to locate the lands inhabited by the Mohawk. What migration patterns do you see?

- Explore indigenous populations closer to your community. What native groups live or lived in your community over time?

- Use the +/- tools located in the lower right corner to zoom in and out on the map until you can view the labels on the map more clearly. Use the toggle switches in the upper left corner to view territories, languages, and treaties for each group of Native peoples.

- Read this blog post to better understand the blending of indigenous beliefs about land ownership and traditional cartography.

Create a simple Land/Territory Acknowledgement statement or placard for your school or community. Use the Native Land map and this passage for research. You and your classmates may work in pairs or small groups, or if working remotely, your teacher may provide you with access to a breakout room or a collaborative document such as Google Slides. Present your findings to your School Board or PTA, asking them to incorporate them into their official meetings and agendas. You may also propose this to your City Council or Board of Supervisors for consideration.

Your teacher may ask you to submit your statement or placard as an exit ticket.

Explain:

Was Abigail Adams America’s first feminist?

A feminist is a person who believes men and women should have equal rights and opportunities. In this segment, we learn more about America’s second First Lady, Abigail Adams, a “Founding Mother.” (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Remember the Ladies.”)

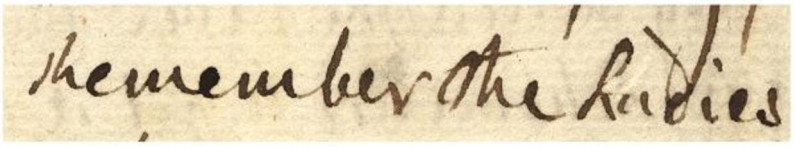

In the video, we hear excerpts from letters written between President John Adams and his wife, Abigail, who urges him to “Remember the Ladies.”

Take some time to view excerpts of the Adams papers as they relate to the letters from the video. You may work with a partner, or if working remotely your teacher may provide access to a breakout room in a video conferencing platform or a collaborative document such as Google Slides.

- What specific requests did Abigail Adams make of her husbands and the Founders?

- Did her request include all women or only some women?

- How did her husband, John Adams, respond?

- How would his response be viewed now through a 21st-century lens?

- How has our thinking about women’s rights and suffrage changed over the years?

- What gender equity work still needs to be done?

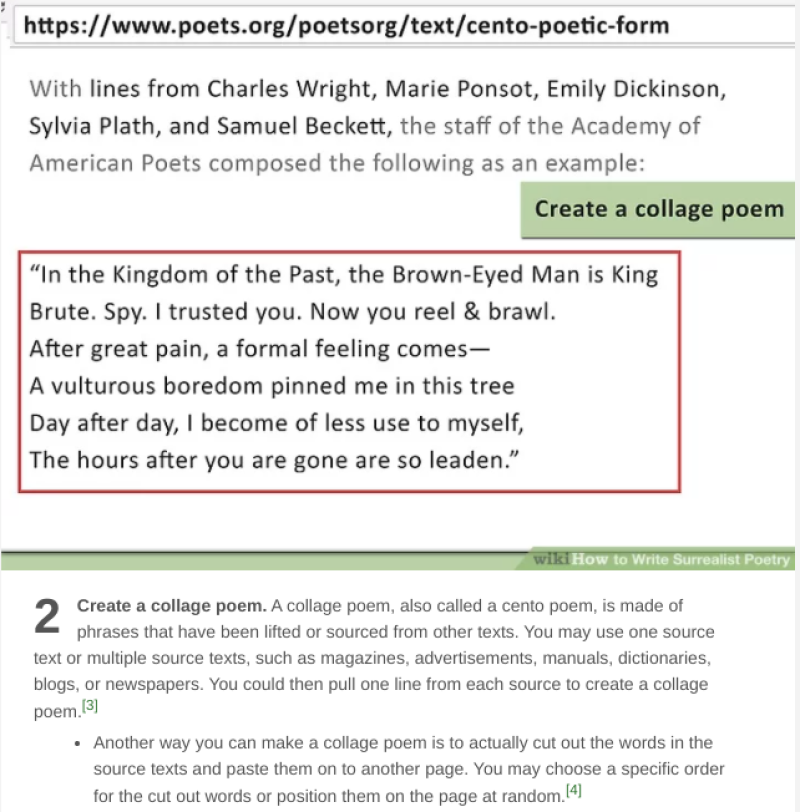

Using words, phrases, and sentences from the letters sent between President John Adams and his wife, Abigail, create a Cento Poem expressing your thoughts on Abigail’s plea and her husband’s response. A Cento Poem (or collage/patchwork poem) is similar to a Blackout poem as you, the reader will select the words of others to create your own poem expressing your thoughts or feelings on a topic. You may choose to copy/paste the content or take a screenshot and crop images from the text. Your teacher will provide you with guidance on the format to save and share your work. We recommend a Gallery walk, either in person or virtually using collaborative slides so you and your classmates can read and discuss your work as a community.

We would love to hear from you and have you or your teacher / a trusted grownup share your poems with us via email or Twitter @newamericanhist as your school safety guidelines permit. Always be sure to cite the sources you borrow from to create your poem! Most of all, be creative and have fun expressing your thoughts on these historic documents. As John called Abigail “saucy,” feel free to make these words your own!

Your teacher may ask you to share your poem as an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

Could placed-based learning help rewrite or reframe the story of America?

For decades, public opinion polls have ranked museums and historic sites as the most trustworthy source of historical information. More than textbooks, newspapers, the internet, and even history teachers! (Ouch!). Museums and historic sites are often supported with public funds and provide place-based learning experiences for students, teachers, and the general public. Place-based learning extends history beyond the classroom walls, out into our communities, and in the locations where people made history in the past. Historian Ed Ayers visits a unique historic site in this segment, making the case for more field experiences for students learning about American history. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Petitioning for Freedom and Wages.”)

Most history textbooks do not associate enslaved African Americans living in the North. People often associate slavery as a strictly Southern practice, and others mistakenly learn or believe that all Northerners were abolitionists. These misconceptions make the case for the importance of place-based learning.

“I want them to know that there was slavery in Massachusetts. I want them to get a sense of the two different lives that were lived here: the lives that were lived by the members of the Royall family, in contrast to the lives that were lived by the enslaved people.”

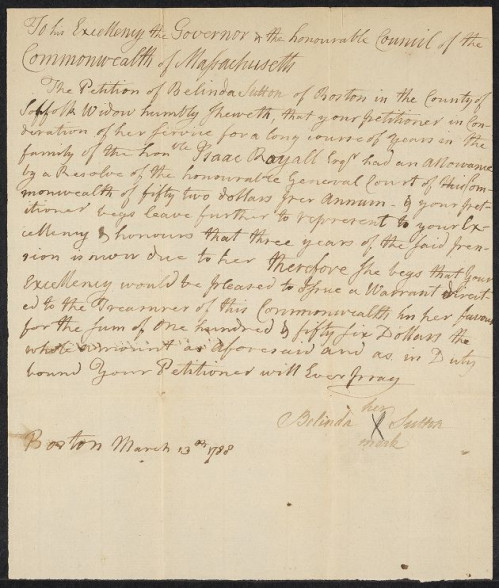

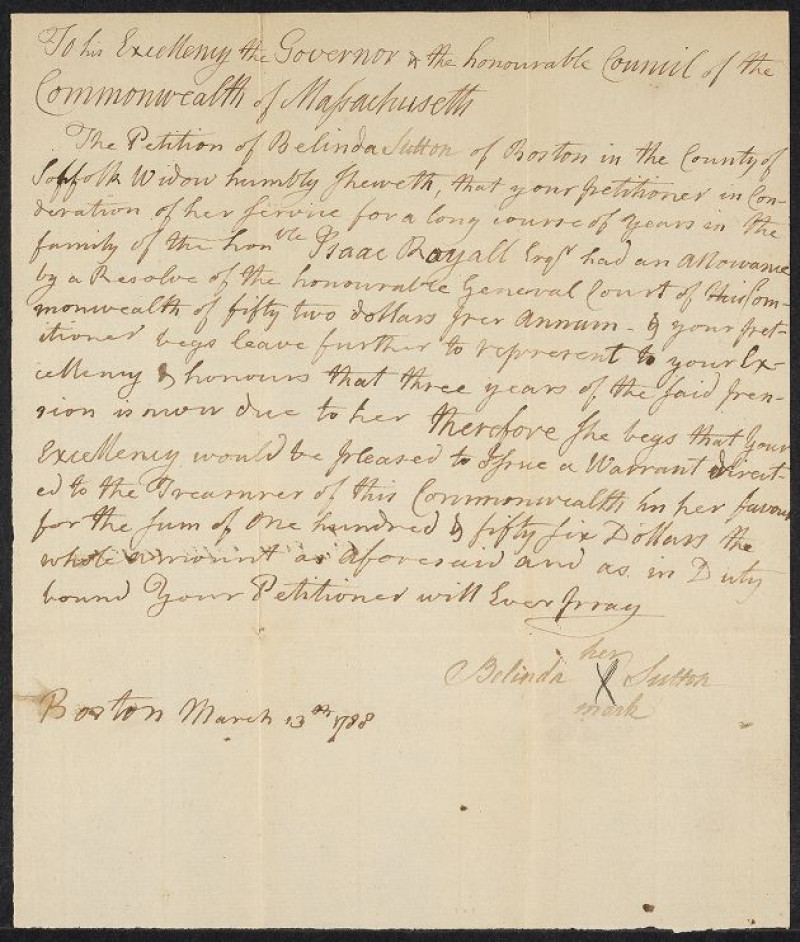

In the video, host Ed Ayers and tour guide Penny Outlaw from the Royall House discuss the danger in teaching and perpetuating historical myths, favoring “cleaned up history” or “teaching children inspiring stories” rather than complete and honest historical narratives. Outlaw makes the case that there is power in preserving historic sites and telling the truth using historical narratives of Americans like Belinda Sutton. Stories like Sutton’s are inspiring, but also teach us historical empathy. Understanding the feelings and lived experiences can help us interpret the past, including the actions and decisions that helped shape our nation.

Take a few minutes to explore more information about Belinda Sutton’s petition.

- How did new scholarship shared in 2015 change historians’ and the public views of the lives of enslaved African American women?

- Why is Sutton’s story considered so unique?

- How does her story change the way you think about the way you previously learned about enslaved African Americans?

- Think about the way you previously learned about the institution of slavery. What sources do you consider to be most trusted?

- What sources seem to “clean up history?”

- Can we teach the truth and still inspire?

Create a local history guidebook or site with your classmates Your teacher may provide access to a collaborative doc or perhaps allow you to help build a Weebly or Google site.

Select a local historical figure or site to explore in more detail. If you can visit a local historical site, park, or museum safely we encourage you to try your own place-based learning experience. If you are unable to visit in person, many museums and historical sites now offer virtual exhibits and tours. A local historical society guide, public or school librarian may help you locate a safe place to visit either in person or online. Always be sure to consult your teacher and/or a trusted adult before you visit.

Take pictures or sketch images to help illustrate what you learned about your community or a local historical figure from your research. Compose a brief description of the person or event, and explain what contributions this person or place made to your community. Help your neighbors understand why they should support these sites or the importance of your school and classmates teaching and learning about honest historical narratives. Consider sharing your guidebook or site with a public audience, perhaps linking it to your school website or asking the site you visited to link it to their website.

We’d love to hear from you about your experience! Share your guidebook or site with us via email or ask your teacher or a trusted adult to share it with us via Twitter @newamericanhist — we hope you enjoy exploring your community!

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

What can we learn from storytelling and dramatizations that differ from textbooks or other non-fiction sources?

The popularity of the Broadway musical Hamilton has created a renewed interest in historical-themed stage productions, films, and television shows. Museums and historical sites are ideal settings for staging historical dramatizations, as they attract audiences who are interested in history, and provide a contextualized setting perhaps more realistic than a traditional theater. Playwright Patrick Gabridge introduces historian Ed Ayers to Cato and Dolly, and shares how staging his play at the old statehouse in Boston transported his audience to another time, helping them see connections between past and present as they get a glimpse of the very real-life struggles faced by women, enslaved African Americans, and people of color during the Revolutionary era. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Bringing New Voices to the Stage.”)

Turn and talk to an elbow partner, or if working remotely your teacher may provide access to a breakout room in a video conferencing platform or a collaborative document such as Google Slides.

- How did staging the play about Cato and Dolly at a historic site enhance the storytelling?

- What material culture did the playwright use to enhance the story and create empathy for the characters?

- What “levers of power” were in progress at the timeframe when the play was set? How did these levers of power differ for Cato? For Dolly?

- In the video, historian Ed Ayers mentions the phrase, “It was a simpler time.” What does this phrase mean, and how does he challenge this concept?

In the video, playwright Patrick Gabridge states:

“We don't know the historical moment we're in. We're trying to make sense of it, just like they were. They didn't know, and we don't know, so it's okay to feel unsettled in times of turmoil, because they felt the same way, and they survived, and we'll find a way.”

At the time this learning resource was developed in 2020, the world was disrupted by a global pandemic, and communities across the United States were increasingly divided as many engaged in protest marches related to social justice issues including systemic racism, economic inequality, and police brutality. The highly contested Presidential Election contributed to increased polarization.

How might Patrick Gabridge’s quote about Cato and Dolly be applied to one or more of the current crises, or another you might have studied in American history? Use the Chalk Talk strategy to share your thoughts with your classmates, or if working remotely, your teacher may allow you to use a collaborative document such as Padlet, Google Docs or Google Slides.

In this final video, Educator L'Merchie Frazier shares the history of the African Meeting House with historian Ed Ayers. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Education in the Wake of the Revolution.”)

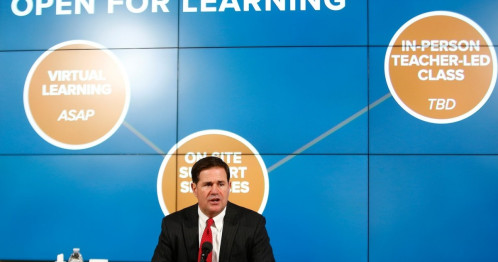

In the video, Frazier describes the extraordinary sacrifices free Black people made to ensure their children would receive an education. During the COVID-19 pandemic, schools were closed across the country for much of the spring of 2020 and into the fall as communities continued to debate the risks v. merits of sending students and teachers back to school during a public health crisis. Some parents hired private tutors or formed “Pandemic Pods,” while others struggled to balance homeschooling their children while continuing to work remotely from home, or for those essential workers, to find daycare options for their young children. Many families, especially in rural communities, are unable to provide access to reliable internet connections, making it even more difficult to continue their children’s education during the pandemic. As non-essential businesses closed, some jobs were eliminated adding further hardships on families struggling to provide basic needs and supporting their children and local schools. Teachers and school leaders, healthcare workers, and local food banks became overwhelmed as they struggled to meet the growing needs of their communities.

This Bunk excerpt explores the nation’s long history of inequality in schools. After reading the excerpt, take a few minutes to explore some of the connected content, using the connections icons and related tags between each excerpt to the one you read about Pandemic Pods.

Thinking back to the Chalk Talk activity you participated in with your classmates, and the Bunk Tags and Connections you just explored, nominate a NEW Bunk Connection or Tag you might suggest between one or more connected excerpts. You may email your suggestions to us at editor@newamericanhistory.org or share via social media (links on our pages) if you are age 14 or older and your teacher or a trusted adult allows. We would love to know what connections you are making using The Future of America’s Past and Bunk!

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

Adams, Abigail. “Abigail Adams Reminds John Adams to "Remember the ladies",” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, accessed December 2, 2020, https://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/672

Adams, John. “John Adams Answers Abigail's Plea to "Remember the Ladies",” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, accessed December 2, 2020, https://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/676

Boonshoft, Mark. “The Undemocratic History of School ‘Pandemic Pods.” Bunk History. New American History, August 5, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/

Dichtl, John. “Most Trust Museums as Sources of Historical Information.” AASLH. American Association for State and Local History, August 12, 2020. https://aaslh.org/most-trust-museums/

Field Studio. “The Revolutions.” Bunk History. New American History, March 16, 2020. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/6973/connections?type=idea

“Native Americans.” Documents of Freedom. Bill of Rights Institute, 2020. https://www.docsoffreedom.org/student/readings/native-americans

Paterson, Daniel. “Cantonment of His Majesty's forces in N. America according to the disposition now made & to be compleated as soon as practicable taken from the general distribution dated at New York 29th. March. [1767].” Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm72002042/

“Peel the Fruit.” Project Zero. Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2015. https://pz.harvard.edu/resources/peel-the-fruit

“Question Starts.” Project Zero. Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2015. https://pz.harvard.edu/resources/question-starts

“Remember Abigail.” Massachusetts Historical Society: Resources. Massachusetts Historical Society, 2019. https://www.masshist.org/rememberabigail/resources

“The Royal Proclamation - October 7, 1763.” Avalon Project. Yale Law School, 2008. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/proc1763.asp

"The Future Of America's Past: The Revolutions." 2020. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com/

Umansky, Leah. “Turn Articles Into Poetry.” The New York Times. The New York Times, November 29, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/03/30/learning/newspaper-poetry.html?searchResultPosition=1