This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

American Visions: The Hudson River School

View Student Version

Standards

C3 Framework:Processes, Rules, and LawsD2.Civ.14.3-5. Illustrate historical and contemporary means of changing societyD2.Civ.14.9-12. Analyze historical, contemporary, and emerging means of changing societies, promoting the common good, and protecting rights.

Human-Environment Interaction: Places, Regions, and CultureD2.Geo.6.6-8. Explain how the physical and human characteristics of places and regions are connected to human identities and cultures. D2.Geo.6.9-12. Evaluate the impact of human settlement activities on the environmental and cultural characteristics of specific places and regions.

Change, Continuity & ContextD2.His.2.3-5. Compare life in specific historical time periods to life today.D2.His.1.6-8. Analyze connections among events and developments in broader historical contexts.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

QD2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

Historical Sources & EvidenceD2.His.9.9-12. Analyze the relationship between historical sources and the secondary interpretations made from them.D2.His.13.3-5. Use information about a historical source, including the maker, date, place of origin, intended audience, and purpose to judge the extent to which the source is useful for studying a particular topic.

National Council for Social Studies:Theme 3: People, Places, and EnvironmentsNational Geography Standards: Standard 4: The physical and human characteristics of placesStandard 6: How culture and experience influence peoples’ perceptions of places and regionsStandard 17: How to apply geography to interpret the past

EAD Framework:PRIMARY THEME: A People with Contemporary Debates & Possibilities Key Concepts: Understand how fundamental American principles—and continuing debates about them—shape current policy debates

Related Driving Questions:HDQ7.4A- How can your learning from US History suggest strategies for how to address our shared contemporary problems?CDQ7.4B- What specific methods have Americans developed for adapting or preserving their society, and what are the strengths and limitations of each as we look towards challenges in the future?

SECONDARY THEME: Our Changing LandscapesKey Concepts: Analyze the impact of people, policy, and cultural norms on landscape and climateRelated Driving Questions:HDQ2.4A- How have different groups of Americans taken responsibility for the landscape of the United States? How do they do so now?HSGQ2.4D- What have some Americans meant by “the frontier”- in political and economic senses- and how has the meaning of that idea changed across centuries?

Suggested Grade Levels: high school (9-12)

Suggested Timeframe: two 90-minute blocks or three to four 45-minute blocks

Suggested Materials: internet access via laptop, tablet or mobile device

Key Vocabulary

Articulate - express (an idea or feeling) fluently and coherently

Commercial-based lifestyle - a lifestyle where individuals buy/sell/trade goods in an open exchange market

Conservation - the prevention of the wasteful use of a resource

Elements - specific objects/people/things in a given work of art

Environmentalist - a person who is concerned with/advocates for the environment

Hypothesis - a proposed explanation made based on evidence as a starting point for further investigation

Ideology - a set of ideas, beliefs and attitudes, consciously or unconsciously held, which reflects or shapes understandings or misconceptions of the social and political world.

Inferences - a conclusion reached based on logic/reason

Market Revolution - taking place in the early 19th century, a dramatic shift in the US economy from a subsistence-based to commercial-based, characterized by a rise of industrial production, connecting disparate regions of the country, and the exchange of goods in the open market

Poster Session - a format for academic conferences where researchers/scholars present their work through visually engaging posters and share knowledge in brief presentations

Respite - a short period of rest/relief from something unpleasant

Sublime - a feeling of overwhelming awe, inspiration, and vastness caused by a reverence for nature. Used to describe the inspiration behind the Hudson River School artists

Subsistence-based lifestyle - a lifestyle where individuals produce/provide the majority of their own goods/food

Utilitarian - designed to be useful or practical rather than attractive

Vacuum - kept separate from other people and activities; in social contexts, "vacuum" most often refers to a lack or absence of something, particularly in relation to a situation, role, or relationship. It can signify a void left by a loss, a lack of guidance or leadership, or a situation where something is considered in isolation from external influences

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tips

New American History Learning Resources may be adapted to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in pairs or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs or Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge. These Learning Resources uses strategies from Facing History (a Gallery Walk), and Project Zero Thinking Routines including the 3-2-1 Bridge and I used to think, now I think, The Observe, Reflect, Question Primary Source Analysis tool from the Library of Congress and Observe, Wonder, Infer strategies are also used, with linked graphic organizers. You may choose to have students make a digital copy or print copies for them as needed. Excerpted connections from Bunk, audio clips from the BackStory podcast archives, StoryMaps from American Visions, and maps from the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond are linked throughout the learning resources, as are. additional resources cited throughout and in the citations section of this learning resource.

These Learning Resources follow a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

For Students:

What role do artists play in society? What value does art bring to one’s life beyond offering a brief respite from the grind of daily life? What can a painting communicate that words cannot? These questions, along with many more, are raised through investigating the Hudson River School, a 19th-century artistic movement that inspired the tradition of American landscape painting.

Engage:

To what extent are works of art a reaction to what is happening within a society?

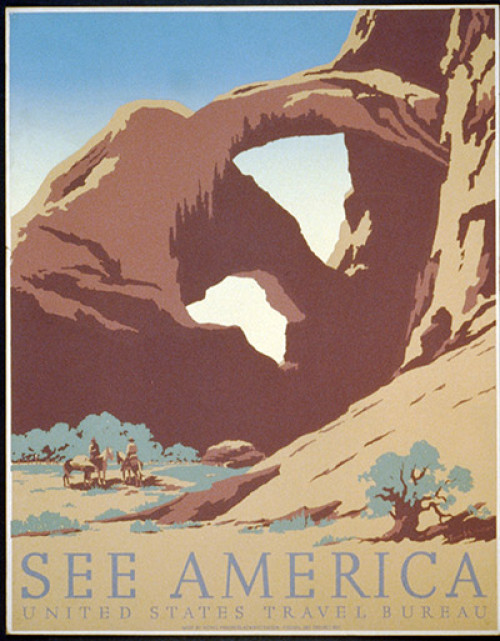

Artists rarely create in a vacuum, disconnected from both immediate and distant communities. Much of the music, theater, literature, and visual or performing arts we consume offers commentary on the societal changes happening around us. Take a moment to examine the photograph below. It was taken by Indian-American photographer Subhankar Banerjee in Barnard Harbor, Alaska.

Utilizing the Observe/Wonder/Infer method, follow these steps: (Use this graphic organizer; your teacher may provide a paper copy.)

- Spend 30 silent seconds just taking in the image. Give equal attention to the image both as a whole and by focusing on specific elements.

- Share/write down/make observations. These observations are solely things that you see in the image. Be mindful not to make any judgments or draw conclusions about what you think might be happening.

- Spend another 30 silent seconds wondering about the image. Imagine that you get to sit down with the photographer and ask them anything.

- Share/write down/ask questions.

- Spend the final 30 silent seconds drawing inferences about the image. This is where you get to hypothesize anything about the image, its creation, and the effects it may/may not have had on viewers.

- Share/write down/make inferences.

Next, read, think about, and share with peers your reaction to the following quote from artist Coco Howard:

“Art has always reflected what’s in our world and in our horizon and what our fears are.”

Turn and discuss with a partner your reactions to Howard’s quote. Share your thoughts on:

- What they’re trying to communicate

- To what degree do you agree/disagree with them

- What “fears” might Subhankar Banerjee’s photograph be reflecting

Finally, read this excerpt from Bunk about Banerjee’s photograph. Take a few minutes to explore the Connections linked to the excerpt in Bunk using the View Connections button.

After reading, work independently or collaboratively, as directed by your teacher, to complete the ‘I used to think, now I think’ graphic organizer.

Plan to share one takeaway from the Bunk excerpt and how it changed/affirmed your thoughts on Banerjee’s photo and Howard’s quote. The following sentence starter is an option:

In the Bunk excerpt, it said______________________________. This [changed/affirmed] my thoughts on Banerjee’s photo and Howard’s quote because________________________________________________________.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

What was the Hudson River School?

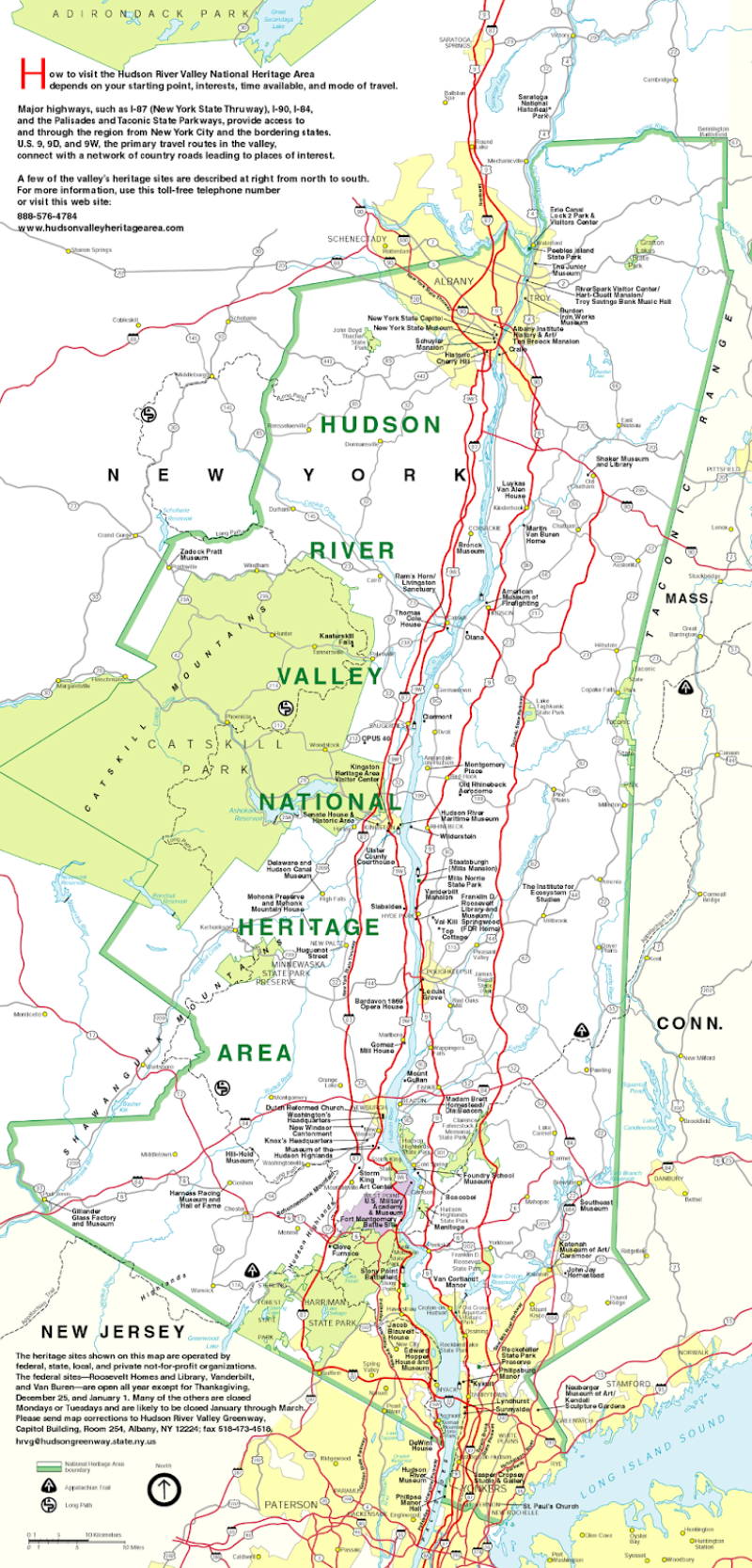

Unlike a “school” in the conventional sense, the Hudson River School was a mid-19th-century artistic movement centered in New York City and the Hudson River Valley to the north.

The painters who belonged to this school celebrated the magnificence and power of nature, referring to their broad subjects as “American scenery.” Artistic movements grow from reactions to existing artistic styles, social and economic conditions, and new ideas. It is no coincidence that the Hudson River School emerged on the heels of a massive transformation to the American economy and a change in lifestyle for many. With the increasing changes in technology and development of new industries, the 19th century saw massive societal and economic changes often referred to as the “Industrial Revolution”. Some historians believe the terminology is not as inclusive as it might be. The alternate terminology, “Market Revolution” helps define the shift from a subsistence-based lifestyle to a commercial-based lifestyle. American farmers and workers began to produce goods to be exchanged in the market rather than producing only what they and their families needed to survive. Regions of the country that were previously disconnected became connected through the digging of canals and the building of roads. It was not only the economy that transformed during this period, but much of America’s landscape itself. Witnessing this transformation, artists sought to capture what they called the sublime, or the power of America’s scenery.

Access this Bunk connection:

Read Nature’s Nation: The Hudson River School & American Landscape Painting, 1825-1876 and Pieces of the Past, a Travelogue entry from historian Ed Ayers as connected in Bunk.

Next, listen to this audio excerpt from the Backstory archives: Scenic Staycation.

Once you have explored these resources, your teacher will help the class split into four groups associated with different geographic areas associated with the Hudson River School:

- Natural Bridge, Virginia

- Cooperstown, New York

- Hudson River, New York

- Catskill, New York

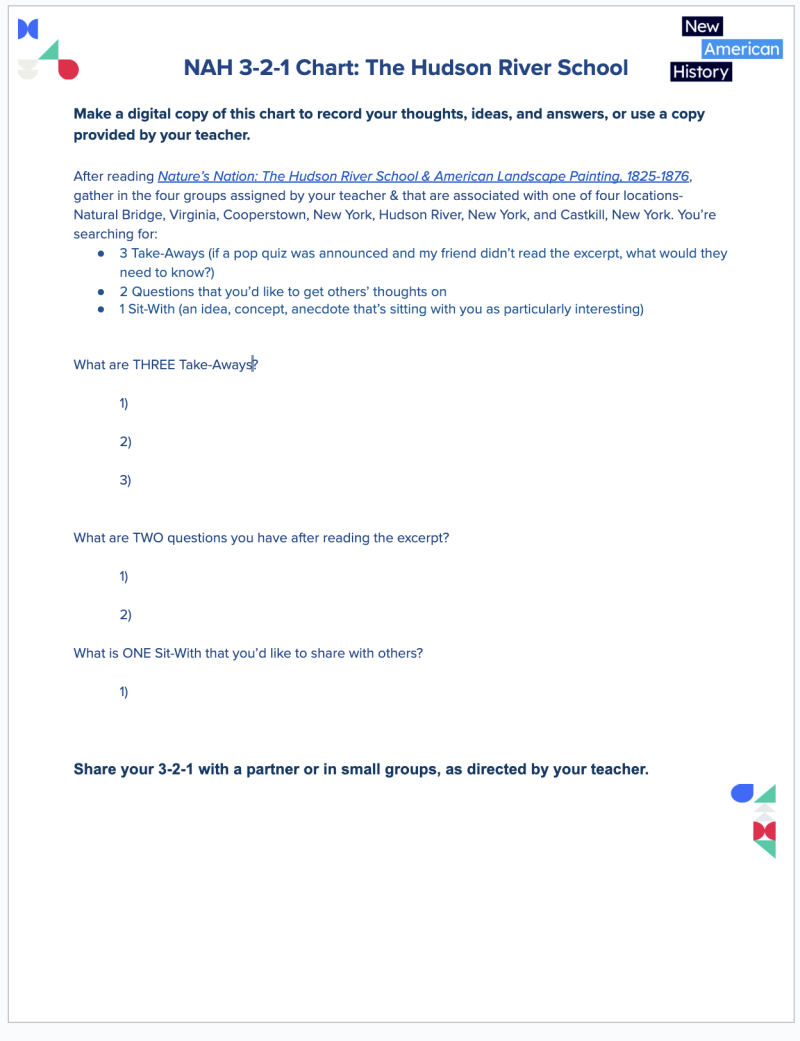

Read the excerpts individually, listen to the BackStory excerpt from 0:00-4:10, and then complete the 3-2-1 Chart.

- 3 Takeaways - Imagine there is a pop quiz and your friend didn’t get a chance to read what you did. What do they absolutely need to know from the excerpt?

- 2 Questions - Something that you’d like to get others’ thoughts on.

- 1 Sit-With - Note an idea, concept, or anecdote that’s sitting with you as particularly interesting.

In those same groups, using the button labeled “View Connections” on Bunk, extend the story of the Hudson River School by visiting the connections below associated with your group’s location.

- Natural Bridge, Virginia: Rekindling the Wonder of Natural Bridge, Once a Testament to American Grandeur

- Cooperstown, New York: Pieces of the Past

- Hudson River, New York: Mettlesome, Mad, Extravagant City

- Catskill, New York: The Hotel at the Heart of the Hudson River School

Revisit artist Cora Howard’s quote:

“Art has always reflected what’s in our world and in our horizon and what our fears are.”

Consider the following questions through the lens of your group’s specific piece:

- What was being “reflected” in the works of Hudson River School artists?

- What seemed to be on the “horizon” (such as new artistic styles) for these artists?

- What might some “fears” have been for these artists?

Finally, as a group using both the broad Bunk piece on the Hudson River School along with your group’s specific geographic piece, compose a Six-Word Story as an exit ticket. Consider making one of your six words something from Howard’s quote.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

What characterizes Hudson River School art?

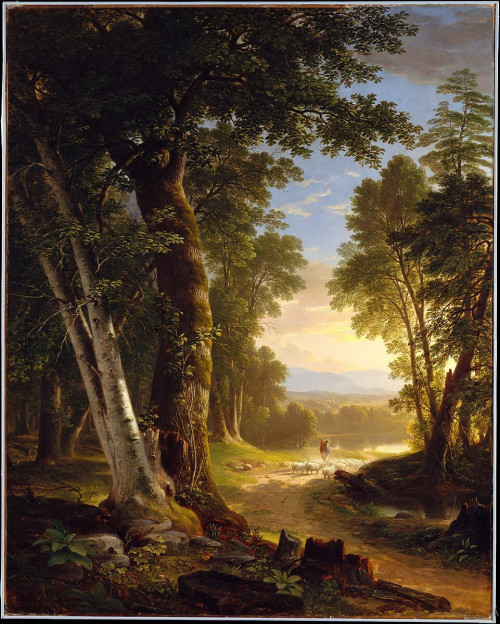

Begin by accessing this selection of Hudson River School works from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“Met”). Using the same strategy from the “Engage” section of this Learning Resource, choose one painting from the Met’s exhibit and go through the following steps with those seated near you.

- Spend 30 silent seconds just taking in the image. Give equal attention to the image both as a whole and focusing on specific elements.

- Share/write down/make observations. These are solely things that you see in the image. Be mindful not to make any judgments or draw conclusions about what you think might be happening.

- Spend another 30 silent seconds generating questions about the image. Imagine that you get to sit down with the photographer and ask them anything.

- Share/write down/create questions.

- Spend the final 30 silent seconds drawing inferences about the image. This is where you get to hypothesize anything about the image, its creation, and the influence it may/may not have had.

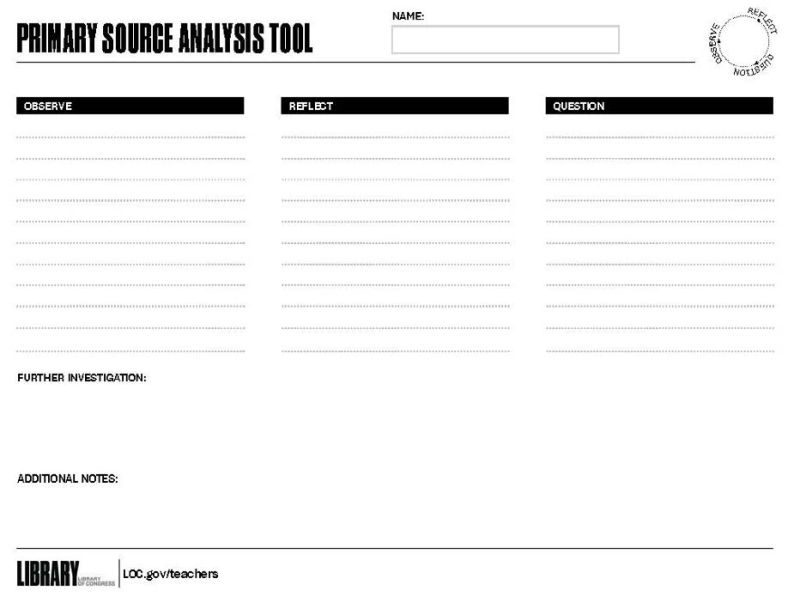

Using the same painting from the opening round, access & complete the Observe, Reflect, Question Primary Source Analysis Tool from the Library of Congress. Your teacher may provide a paper copy or allow you to access this digitally.

Next, access this National Expansion & Reform timeline from the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Next, access this National Expansion & Reform Timeline from the Gilder Lehrman Institute. Add two or three observations, reflections, and questions to your Primary Source Analysis tool. Your comments should connect at least one event from the period leading up to - and be concurrent with - the Hudson River School. For example, what were some likely influences felt by the artist of the work you chose to analyze?

Complete the following template prompt to articulate the connection between an event from the Expansion & Reform timeline and the Hudson River School:

In [artist + title of work], one can see the influence of [event from timeline] through…[connections you’ve identified and how they are demonstrated].

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

What did Hudson River School artists see as essential elements in their work?

View this brief video on the Hudson River School’s place within the greater scope of the history of landscape painting. As you watch, collect a list of “essential elements” that seem to come up across different artists’ works.

In addition to his painting, Hudson River School artist Thomas Cole also wrote about the artistic movement itself. To see how Cole fits into the broader story of Americans exploring their relationship with nature in the early 19th century, access this StoryMap.

In Chapter Two, scroll down to Thomas Cole:

In the January 1836 edition of The American Monthly Magazine, Cole wrote an Essay on American Scenery in which he articulated his reverence for the American landscapes that he and other Hudson River School artists were aiming to portray in their work. In his essay, Cole identifies “Elements of American Scenery,” among which are:

Divide into groups with each taking one of the five “Essential Elements” as your topic. Take a moment to read Cole’s words on your group’s element (Wildness, Mountains, Water, Forests, Sky). If helpful, use the tool Rewordify for language that feels particularly challenging.

Next prepare for a Gallery Walk by printing out or digitally displaying your group’s chosen painting from the Met exhibit. Talking points for your Gallery Walk should include the following:

- Title of the work & artist

- Year it was created and any pertinent events happening concurrently that might have influenced the work

- Guiding viewers through the piece, giving close attention to elements that Cole referred to in his essay

As a concluding step, return to your original “essential elements” list from the opening film clip. Discuss any additions, omissions, or changes. Consider rating the elements in order of “most” to “least” common in Hudson River School works.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

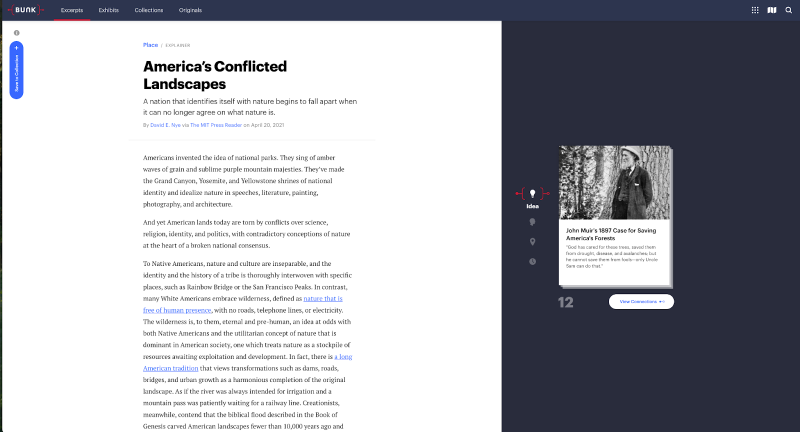

From the Hudson River School perspective, what exactly does nature represent?

Americans have a long and complicated relationship with nature. One version of that relationship can be described as “utilitarian.” Within this view, nature is seen as useful for human progress. Another version of the relationship with nature can be described as “environmentalist,” reflecting much of today’s conservation ideology and protection of species and landscapes. In this excerpt from Bunk, historian David Nye poses the question: What does nature represent?

Working in small groups as directed by your teacher, read this Bunk excerpt:

Take a few minutes to explore the connections between the excerpt and other related content in Bunk.

Take a few minutes to explore the connections between the excerpt and other related content in Bunk.

In your small groups, discuss and share your thoughts on these questions posed by Nye:

- Does nature represent eternity, ancestors, science, the present, the future, and/or a young earth?

- Is nature to be revered, conserved, exploited, or sacrificed?

Now, imagine that your group is presenting at a poster session at an upcoming educational conference on Americans’ relationship with nature. You’ll be the resident experts on the Hudson River School and its artists’ views on nature’s purpose. (For more information on poster sessions, the American Library Association has helpful explanations and examples.)

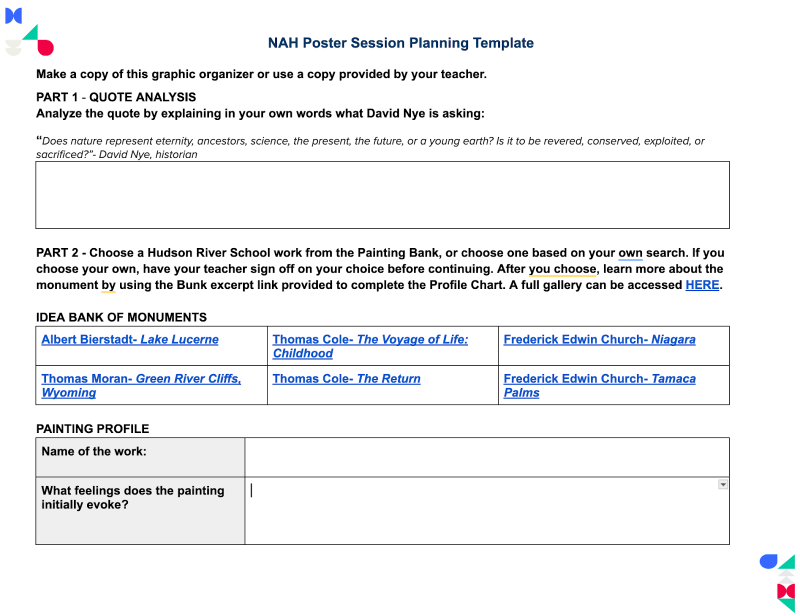

Work collectively to plan your poster using this Graphic Organizer.

Plan to hold a poster session in your classroom or a more visible space at school, if time permits and your teacher extends the learning experience. You might invite other classrooms to your poster session, or perhaps display them at a public meeting of organizations such as the PTA/PTO, a local municipal meeting (such as a city or town council meeting), or in partnership with a local art gallery.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

n.d. American Panorama - Canals. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/canals/#canal=22&year=1849&loc=8/0.464/17.042.

Archive, Backstory. 2018. “Scenic Staycation.” Backstory Archive. https://backstory.newamericanhistory.org/episodes/wish-you-were-here/2/.

Dunaway, Finis. 2023. “Did One Photograph Change the Fate of the Arctic Wildlife Refuge?” Bunk History. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/perspective-did-one-photograph-change-the-fate-of-the-arctic-wildlife-refuge.

Ferber, Linda. 2016. “"Nature's Nation: The Hudson River School and American Landscape Painting, 1825-1876.” Bunk History. https://www.bunkhistory.org/places/browse/10133?place=1267&type=ideas&id=5293.

Gilder Lehrman, 2009. “Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Timeline: National Expansion & Reform, 1815-1860. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/online-exhibitions/timeline-national-expansion-and-reform-1815-1860.

“Hudson River Valley Map - HRVI.” n.d. Hudson River Valley Institute. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.hudsonrivervalley.org/hudson-river-valley-map.

Nye, David. 2021. “America's Conflicted Landscapes.” Bunk History. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/americas-conflicted-landscapes.

Schagen, Sarah van. 2020. “Portrait of an Artist as a Climate Activist.” Grist. https://grist.org/article/2009-08-05-portrait-of-an-artist-as-a-climate-activist/

“The Hudson River School.” 2004. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/the-hudson-river-school.

“The Hudson River School explained.” 2023. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQKdbIuCIyM.

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc