This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Jefferson & Adams: Divided Friends

Key Vocabulary

Adams, John Quincy - sixth president of the U.S., eldest son of second president John Adams; part of the U.S. delegation that negotiated an end to the War of 1812

Barbary States - the present-day countries of Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia and the site of wars between the U.S. and these states over the pirating of U.S. merchant ships passing through the region

Burr, Aaron - U.S. politician, lawyer, and founder who served as the third vice president from 1801 to 1805 in the Jefferson Administration; he famously killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel in 1804

Civil discourse - respectful discussion of shared concerns

Democratic-Republicans - a political party founded in 1792 by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, advocated for liberty, decentralization of political power, and the French Revolution

Federalists - a political party founded in 1789 that supported a strong central government; members included Alexander Hamilton and John Adams

Gallic despotism - “Gallic” refers to the French, and “despotism” is a government in which a leader has absolute power; this phrase was referring to the French Revolution (1789-1799)

Homespun - simple and unsophisticated; also cloth or yarn spun at home

Mazzei, Philip - Italian-born friend of Thomas Jefferson who supported American independence from Britain

Paine, Thomas - A British-born Patriot and statesman during the American Revolution who wrote the political pamphlet “Common Sense” that sought to convince colonists to rebel against the British Empire

Patriots - people who supported the American Revolution

Presidential Election of 1800 - Vice President Thomas Jefferson beat the incumbent President John Adams, marking the first time an incumbent president gave up power

Rush, Benjamin - Founder and medical doctor from Pennsylvania who signed the Declaration of Independence and was active in the Sons of Liberty; credited with helping to reconcile the friendship of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams

Second Continental Congress - the meeting from 1775 to 1781 in Philadelphia, in which delegates from the Thirteen Colonies met to adopt the Declaration of Independence and the first U.S. Constitution, which was then called the Articles of Confederation

Read for Understanding:

During the American Revolution, an unlikely friendship developed between two founders–both attorneys, who hailed from very different backgrounds. Thomas Jefferson was a Virginia planter, and John Adams was a man of more modest means from Massachusetts. They served together in the Second Continental Congress and later spent time in Europe as diplomats representing the United States. But as political parties formed in America, they had a falling out. This learning resource tracks the stages of the Jefferson-Adams partnership: from friends, to rivals, to a late-in-life reconciliation.

Engage:

How divisive was the political culture in the U.S. in 1800?

The presidential election of 1800 was a bitter political contest between sitting President John Adams and challenger Thomas Jefferson. Adams' supporters warned that if Jefferson were elected, “the navy is laid up, the ships are to rot at our wharves, our commerce is again to be plundered, our farmers are to be impoverished, and our merchants ruined.” (Connecticut Courant, August 28, 1800)

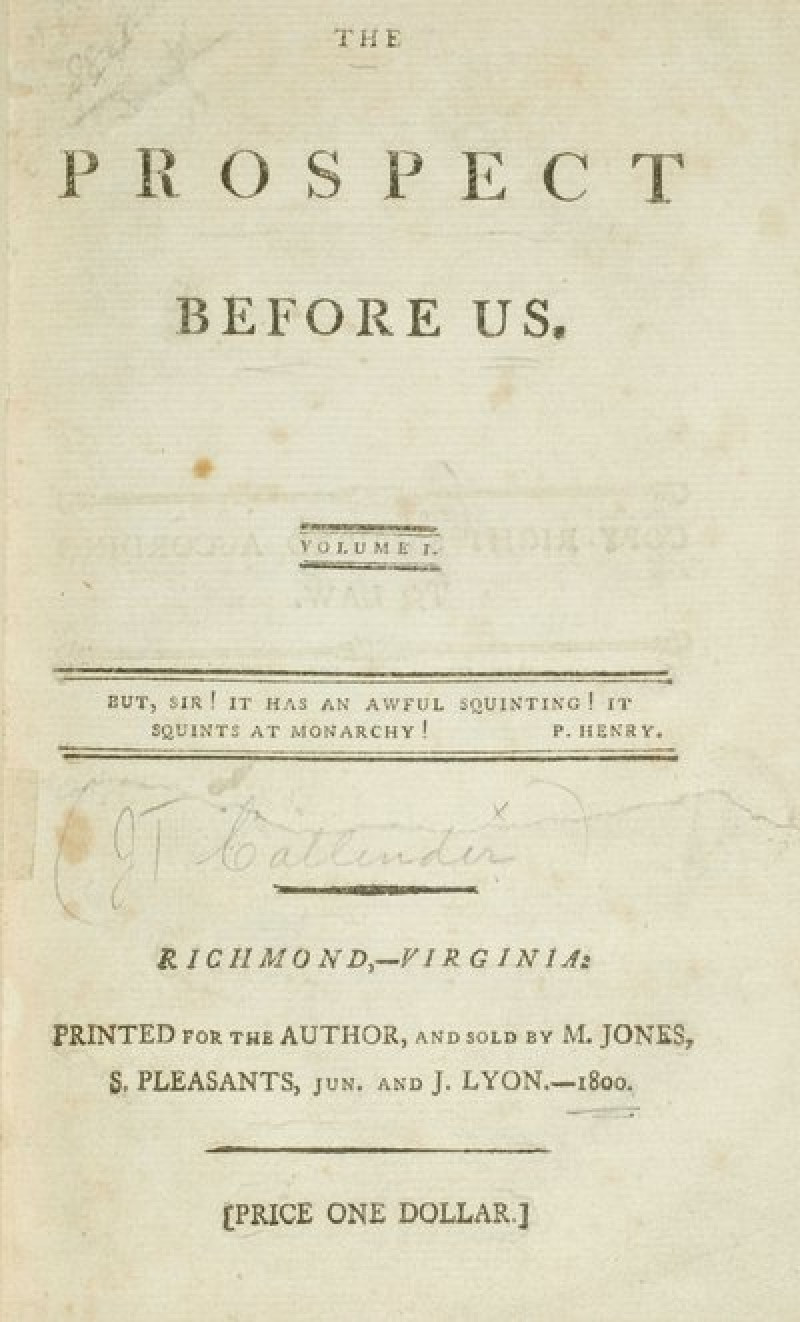

And Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans - represented here by James Callender in an 1800 publication called The Prospect Before Us - stated that “the design of this book is to exhibit the multiplied corruptions of the Federal Government, and more especially the misconduct of the President, Mr. Adams.” (James Callender, The Prospect Before Us, 1800)

The friendship between the two pivotal Founders deteriorated, and American partisan politics was born.

First, analyze the political cartoon “The Providential Detection,” created by an unknown artist who supported Adams during the 1800 campaign.

Use the See/Wonder/Connect thinking routine to examine the cartoon:

1. What do you notice? Make many observations. Observations are solely things that you see.

2. What questions do you have? What do you wonder about? Imagine sitting down with the artist and asking them anything.

3. How does this cartoon connect to politics in America today? What does it remind you of?

After you answer the questions independently, share your responses as groups of three or four. Nominate a record keeper, and record your answers using this graphic organizer. Then, nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class. Your teacher may allow you to make a digital copy or use a paper copy provided by your teacher.

After the discussion, share the story of the cartoon and its symbols:

“In this cartoon, Thomas Jefferson kneels before the altar of Gallic despotism as God and an American eagle attempt to prevent him from destroying the United States Constitution. He is depicted as about to fling a document labeled “Constitution & Independence U.S.A.” into the fire fed by the flames of radical writings. Jefferson's alleged attack on George Washington and John Adams in the form of a letter to Philip Mazzei falls from Jefferson's pocket. Jefferson is supported by Satan, the writings of Thomas Paine, and the French philosophers.” Library of Congress.

The image of Jefferson kneeling before the altar of Gallic despotism is an expression meant to criticize Jefferson's support of the radical elements of the French Revolution. A patriotic eagle is shown protecting the U.S. Constitution from Jefferson's touch. The note labeled Mazzei in his right hand refers to Jefferson’s alleged attack on George Washington and John Adams in a letter he wrote to his friend Philip Mazzei, in which he says the two men had been too supportive of British-style governing. Satan appears to defend Jefferson in the scene, and the writings of Thomas Paine and the French philosophers attempt to paint him as a pro-French radical. In short, the cartoon accused Jefferson of being un-American, un-Godly, and a political radical.

After reading the story of the symbols, answer these questions independently first:

- Why do political campaigns use sensationalism?

- To what extent do you think sensational ads are effective at convincing voters?

Then, share your responses in groups of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

The presidential election of 1800 spawned partisan politics, and political cartoons were not the only evidence of that.

Next, read the following article that the Albany (NY) Gazette published on July 7, 1800. Then answer the questions that follow.

1. According to the article, what has happened?

2. Who do you think created this report? Why would someone want to circulate this news?

3. How is this an example of sensationalism in American politics?

Share your responses in the same group of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

How different were Jefferson and Adams?

Jefferson and Adams died on the same day, July 4, 1826. They both studied law and loved reading books about history, philosophy, and politics. They both traveled to Europe as American diplomats. And they worked together to finalize the Declaration of Independence.

Despite their similar roles in fighting for American independence, Jefferson and Adams were very different Revolutionary-era leaders.

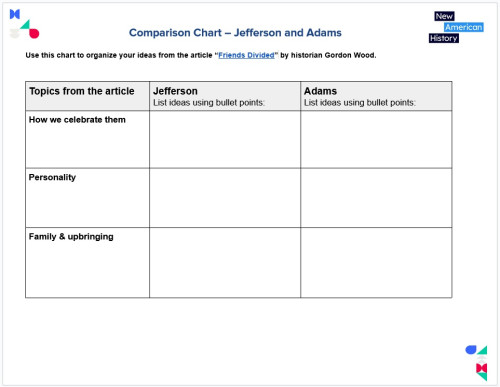

Compare the two men by reading historian Gordon Wood's article “Friends Divided.”

As you read through the article, complete this chart to organize your ideas.

After you complete the chart, use your ideas to discuss your responses to the following questions in groups of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

1. In your opinion, what are the most important differences between Adams and Jefferson? Use specific ideas from the reading to support your claims.

2. At the end of the reading, historian Wood uses the words of Abraham Lincoln to explain why we are more likely to honor Jefferson, and not Adams, today in American society. To what extent is it fair to honor Jefferson and not Adams today?

3. What are the benefits and drawbacks to “honoring” and glorifying any American historical figure? Use specific ideas from the reading to support your claims.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

How did Jefferson and Adams’ relationship change from that of early allies to political rivals?

During the American Revolution, Jefferson and Adams were pivotal Patriots. Jefferson had the pen. Adams had the tongue. They worked closely as political partners when the Second Continental Congress began meeting in Philadelphia in 1775. However, their friendship deteriorated in the 1790s, when the new nation split into two political factions, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Adams beat Jefferson in the 1796 presidential election, and, under the early rules of the Constitution, Jefferson became his vice president, despite disagreeing with most of Adams´ policies.

Evidence of early allies

As a retiree, Adams wrote a letter in 1822 to friend Timothy Pickering, in which he reminisced about the story of how the Declaration of Independence was written. Read this excerpt from the National Archives’ Founders Online archive.

The Committee met, discussed the subject, and then appointed Mr. Jefferson & me to make the draught; I suppose, because we were the two highest on the list. The Sub-Committee met; Jefferson proposed to me to make the draught. I said I will not; You shall do it. Oh No! Why will you not? You ought to do it. I will not. Why? Reasons enough. What can be your reasons? Reason 1st. You are a Virginian, and Virginia ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason 2d. I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular; You are very much otherwise. Reason 3d: You can write ten times better than I can. “Well,” said Jefferson, “if you are decided I will do as well as I can.” Very well, when you have drawn it up we will have a meeting.

A meeting we accordingly had and conn’d the paper over. I was delighted with its high tone, and the flights of Oratory with which it abounded, especially that concerning Negro Slavery, which though I knew his Southern Bretheren would never suffer to pass in Congress, I certainly never would oppose. There were other expressions, which I would not have inserted if I had drawn it up; particularly that which called the King a Tyrant. I thought this too personal, for I never believed George to be a tyrant in disposition and in nature; I always believed him to be deceived by his Courtiers on both sides of the Atlantic, and in his Official capacity only, Cruel.

Next, answer the following questions on your own. Then discuss your responses in groups of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

- What reasons did Adams give for wanting Jefferson to write the Declaration, and what does this tell you about how Adams viewed Jefferson?

- What did Adams compliment and criticize about the Declaration?

In 1786, John Adams was in London and Thomas Jefferson was in Paris, each on diplomatic missions. At the time, the Barbary States of northern Africa were targeting American trade ships in the Mediterranean Sea, demanding that they make payments in exchange for a safe passage. Jefferson wrote to Adams on July 11, arguing for war instead of cooperation. However, Jefferson’s willingness to change his mind based on what Adams thought indicates the respect he had for him.

Read this excerpt from the letter, as also preserved in Founders Online.

You have viewed the subject, I am sure in all its bearings. You have weighed both questions with all their circumstances. You make the result different from what I do. The same facts impress us differently. This is enough to make me suspect an error in my process of reasoning tho’ I am not able to detect it. It is of no consequence; as I have nothing to say in the decision, and am ready to proceed heartily on any other plan which may be adopted, if my agency should be thought useful…. I add nothing therefore on any other subject but assurances of the sincere esteem and respect with which I am Dear Sir your friend & servant.

- What phrases show that Jefferson values Adams' judgment, even if he disagrees?

- How does this passage support the idea that Jefferson respects Adams?

Answer the questions above on your own. Then discuss your responses in groups of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

To summarize the two letter excerpts use the Headlines Thinking Routine:

- Write a headline that captures how Jefferson and Adams were allies.

- How does your headline differ from what you would have said yesterday?

Share your headline with a partner.

Evidence of rivalry

The presidential election of 1800 pitted incumbent John Adams against Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson and Aaron Burr ran together on the Democratic-Republican Party ticket, while Adams led the opposing Federalist Party. In these early days of America, candidates did not campaign directly, but they didn't prevent the mud-slinging and vicious attacks by surrogates.

EXAMPLE #1 – Examine this excerpt from a Philadelphia newspaper:

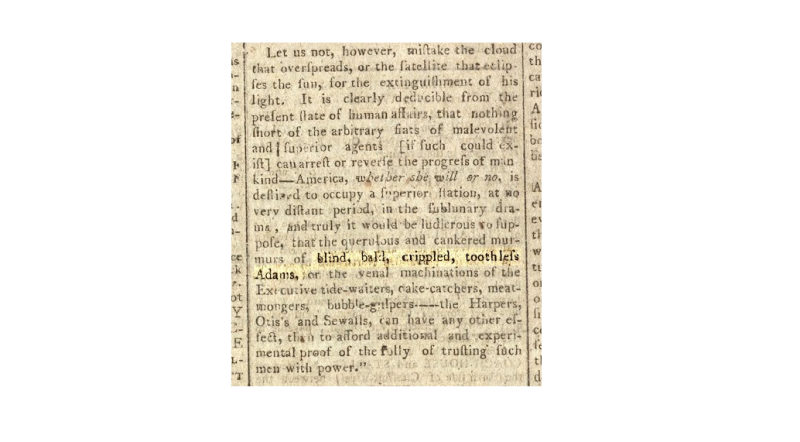

On April 27, 1798, the Aurora (PA) General Advertiser published an anonymous letter that warned readers not to listen to the “querulous and cankered murmurs of blind, bald, crippled, toothless Adams.”

- What two slurs do you think are the most vicious against Adams?

- To what extent is this excerpt like something you'd read online from a political campaign today?

Answer the questions above on your own. Then discuss your responses in groups of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

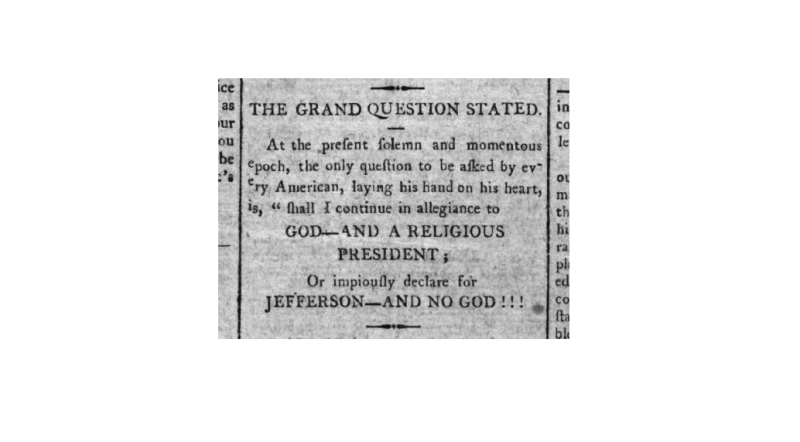

EXAMPLE #2 – Read the excerpt from a Federalist newspaper called the Gazette of the United States, printed during the 1800 campaign and archived in the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America collection.

"At the present solemn and momentous epoch, the only question to be asked by every American, laying his hand on his heart, is 'Shall I continue in allegiance to GOD - AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT; or impiously declare for JEFFERSON - AND NO GOD!!!"

- What is the purpose of this author's writing?

- How effective do you think it would have been in convincing voters? Explain.

Answer the questions above on your own. Then discuss your responses in groups of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

To summarize the two examples use the Connect-Extend-Challenge thinking routine:

Connect – How do the quotes connect to what you already know about Adams, Jefferson, and this historical moment?

Extend – What new ideas do you get from these quotes that expand your understanding?

Challenge – How do the quotes contradict each other? What tensions or differences stand out?

Your teacher will lead a whole-class discussion using the questions.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

How did Jefferson and Adams reconcile their differences? What can we learn from this reconciliation?

Benjamin Rush, fellow signer of the Declaration and friend of both Jefferson and Adams, wrote to Adams in 1812 - after Adams and Jefferson had reconciled - saying: “I rejoice in the correspondence which has taken place between you and your Old friend Mr. Jefferson. I consider you and him, as the North and South poles of the American Revolution. Some talked, some wrote, and some fought to promote & establish it, but you and Mr. Jefferson thought for us all.” From their reconciliation in 1812 to their deaths on the same day – July 4, 1826 – they exchanged 158 letters: 109 from Adams and 49 from Jefferson.

“You and I ought not to die before we have explained ourselves to each other.”

Breaking the ice

After 11 years of avoiding each other, Adams sent a letter to Jefferson on January 1, 1812, to rekindle the friendship that the presidential election of 1800 had destroyed. He included in the letter “Two Pieces of Homespun,” in other words, the transcripts of two speeches that his son John Quincy Adams had given as a student at Harvard University.

Read the entire letter and answer the questions that follow:

Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, January 1, 1812.

Dear Sir, As you are a Friend to American Manufactures under proper restrictions, especially Manufactures of the domestic kind, I take the Liberty of Sending you by the Post a Packett containing two Pieces of Homespun lately produced in this quarter by One who was honoured in his youth with Some of your Attention and much of your kindness.

All of my Family whom you formerly knew are well. My Daughter Smith is here and has Successfully gone through a perilous and painful Operation, which detains her here this Winter, from her Husband and her Family at Chenango: where one of the most gallant and Skilful Officers of our Revolution is probably destined to Spend the rest of his days, not in the Field of Glory, but in the hard Labours of Husbandry.

I wish you Sir many happy New years and that you may enter the next and many Succeeding years with as animating Prospects for the Public as those at present before us. I am Sir with a long and Sincere Esteem your Friend and Servant - John Adams

Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, January 1, 1812, courtesy of the National Archives Founders Online archive.

- What topics does Adams choose to talk about in his first communication with Jefferson in 11 years? Why do you think he chooses them?

- Would you have chosen to renew a friendship in this way, or would you have chosen a different way? Explain.

Answer the questions above on your own. Then discuss your responses in groups of three or four. Nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

Two letters that show mutual respect

Read the following letter and answer the questions that follow:

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, January 21, 1812

…A letter from you calls up recollections very dear to my mind. it carries me back to the times when, beset with difficulties & dangers, we were fellow laborers in the same cause, struggling for what is most valuable to man, his right of self-government. laboring always at the same oar, with some wave ever ahead threatening to overwhelm us & yet passing harmless under our bark we knew not how, we rode through the storm with heart & hand, and made a happy port. still we did not expect to be without rubs and difficulties; and we have had them…

...I have given up newspapers in exchange for Tacitus & Thucydides, for Newton & Euclid; & I find myself much the happier. sometimes indeed I look back to former occurrences, in remembrance of our old friends and fellow laborers, who have fallen before us. of the signers of the Declaration of Independance I see now living not more than half a dozen on your side of the Patomak, and, on this side, myself alone. you & I have been wonderfully spared, and myself with remarkable health, & a considerable activity of body & mind. I am on horseback 3. or 4. hours of every day; visit 3. or 4. times a year a possession I have 90 miles distant, performing the winter journey on horseback. I walk little however; a single mile being too much for me; and I live in the midst of my grandchildren, one of whom has lately promoted me to be a great grandfather. I have heard with pleasure that you also retain good health, and a greater power of exercise in walking than I do. but I would rather have heard this from yourself, & that, writing a letter, like mine, full of egotisms, & of details of your health, your habits, occupations & enjoiments, I should have the pleasure of knowing that, in the race of life, you do not keep, in it’s physical decline, the same distance ahead of me which you have done in political honors & atchievements. no circumstances have lessened the interest I feel in these particulars respecting yourself; none have suspended for one moment my sincere esteem for you; and I now salute you with unchanged affections and respect…

Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, July 15, 1813, courtesy of the National Archives Founders Online archive

- What do you think Jefferson means by “we rode through the storm with heart & hand, and made a happy port”?

- Identify two phrases that grab your attention that show how Jefferson respects Adams.

Answer the questions above on your own. Then discuss your responses with a partner. Nominate one partner to report, then discuss as a class.

Then read the next letter and answer the questions that follow:

Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, July 15, 1813

Let me now ask you, very Seriously my Friend, Where are now in 1813, the Perfection and perfectability of human Nature? Where is now, the progress of the human Mind? Where is the Amelioration of Society? Where the Augmentations of human Comforts? Where the diminutions of human Pains and Miseries? I know not whether the last day of Dr young can exhibit; to a Mind unstaid by Phylosophy and Religion, for I hold there can be no Philosophy without Religion; more terrors than the present State of the World.

When? Where? and how? is the present Chaos to be arranged into order?

There is not, there cannot be, a greater Abuse of Words than to call the Writings of Calender, Paine, Austin and Lowell or the Speeches of Ned. Livingston and John Randolph, Public Discussions. The Ravings and Rantings of Bedlam, merit the Character as well; and yet Joel Barlow was about to record Tom Paine as the great Author of the American Revolution! If he was; I desire that my name may be blotted out forever, from its Records.

You and I, ought not to die, before We have explained ourselves to each other.

I Shall come to the Subject of Religion, by and by. your Friend -John Adams.

Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, July 15, 1813 courtesy of the National Archives Founders Online archive.

- What was going on in 1813 to make Adams use the phrase “the present chaos”?

- How does this letter show the difference in worldview between Adams and Jefferson?

Answer the questions above on your own. Then discuss your responses with a partner. Nominate one partner to report, then discuss as a class.

Summing up questions:

- What can the relationship that Adams and Jefferson had teach us about America’s political system?

- How are Jefferson and Adams similar to today’s political leaders in America? How are they different?

- To what extent do you think a reconciliation of political rivals could happen today?

Answer the questions above on your own. Then discuss your responses with a partner. Nominate one partner to report, then discuss as a class.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

How can we practice civil discourse?

Play the Feast of Reason: Friends & Foes Edition, a variation of a card game created by Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. You may use the Google Slides version linked above, or a paper copy as directed by your teacher.

Thomas Jefferson was known to host elaborate dinners that sparked good conversation. The game asks players to use playing cards with conversation prompts, in order to share stories and listen to each other’s ideas - in other words, to practice civil discourse.

First, assign a host to guide the conversation and read the cards. The host will start the game by reading the "Toast" card.

Next, move through each of the four “courses” of questions: the breadbasket, the appetizer, the entrees, and the dessert. Place the “Salt & Pepper” and “Back-Burners” questions at the center of the table. Anyone can use these prompts at any time to spice up the conversation or cool things down.

“I never considered a difference of opinion in politics, in religion, in philosophy, as cause for withdrawing from a friend.”

After the game:

Answer these questions independently. Then discuss the answers as a group.

- What is one thing you learned about another person or about the world in general?

- Why is it important to listen to and understand different ideas about how people see the world?

- What is civil discourse?

- Why do you think we struggle to practice civil discourse in American society today?

- What action steps can we carry out to improve?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations

Bache, William Franklin. Aurora General Advertiser (Philadelphia, PA). April 27, 1798. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/page-2-the-aurora-general-advertiser-april-27-1798-bache-william-frankling/5gHsKdK0H1U_CQ?hl=en

Burleigh. “To the People of the United States,” Connecticut Courant, September 15, 1800. Google Arts & Culture. A Nation Divided: The Election of 1800. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/to-the-people-of-the-united-states-september-15-1800-burleigh-connecticut-courant/mwGsTnI8bMhT5g?hl=en

Callender, James. The Prospect Before Us. (Richmond, VA).1800, Printed for the author and sold by M. Jones, S. Pleasants & J. Lyon. Accessed November 1, 2025. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL7006705M/The_prospect_before_us Accessed November 1, 2025.

“The Election of 1800 - American History - Thomas Jefferson, John Adams.” The Lehrman Institute. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://lehrmaninstitute.org/history/1800.html

“Fake News Isn’t New: Researching Its History with NYPL’s e-Resources.” The New York Public Library. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2017/08/23/fake-news-isnt-new

Feast of Reason: Friends & Foes Edition. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1AFBiDe5Aua9XMFLmbnRpH6FlTciJ3RUcEVyBXQQHEhE/edit?usp=sharing

“Founders Online: From John Adams to Timothy Pickering, 6 August 1822.” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-7674

“Founders Online: Resumption of Correspondence with John Adams, Followed by John ...” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-04-02-0296-0002

“Founders Online: Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 21 January 1812.” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-04-02-0334

“Founders Online: Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 11 July 1786.” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-10-02-0058

“Founders Online: John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, 15 July 1813, with Postscript ...” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0247

Gazette of the United States, & Daily Advertiser. (Philadelphia, PA), 13 Sep 1800. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84026272/1800-09-13/ed-1/

Lerche, Charles O. “Jefferson and the Election of 1800: A Case Study in the Political Smear.” The William and Mary Quarterly 5, no. 4 (1948): 467–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/1920636.

“Thomas Jefferson Establishing a Federal Republic.” Library of Congress, April 24, 2000. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jefffed.html#136

Wood, Gordon. “Friends Divided - Colonial Williamsburg.” Trend & Tradition Magazine. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/discover/resource-hub/trend-tradition-magazine/trend-tradition-spring-2019/friends-divided/

Zielinski, Adam. “The Election of 1800: Adams vs Jefferson.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/election-1800-adams-vs-jefferson