This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Is the Rule of Law Essential to “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions”?

View Student Version (HS)

Standards

C3 Framework:D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

D2.Civ.10.9-12. Analyze the impact and the appropriate roles of personal interests and perspectives on the application of civic virtues, democratic principles, constitutional rights, and human rights.

National Council for Social Studies:Theme 5: Individuals, Groups, and InstitutionsTheme 6: Power, Authority, and Governance

EAD Roadmap:DESIGN CHALLENGE: Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

THEME: Institution and Social Transformation(CSGQ5.3F) How can we learn to have productive discussions about controversial issues that have existential stakes for some participants?(HDQ5.3A) How have the different legal statuses of different sections of the American population affected the development of the United States over time?A New Government and Constitution(Overarching Thematic Question) What is law?(CSGQ4.2A) Why is the concept of … the rule of law important for a democracy?Changing Landscapes(HSGQ2.3G) What roles were played by U.S. national self-interest and power, balanced with American views of justice, in both founding and expansion?

Teacher Tip: Think about what students should be able to KNOW, UNDERSTAND and DO at the conclusion of this learning experience. A brief exit pass or other formative assessment may be used to assess student understanding. Setting specific learning targets for the appropriate grade level and content area will increase student success.

Suggested Grade Levels: High School (9-12)

Suggested Timeframe: 3-4 ninety-minute block classes.

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet, or mobile device; printer, scissors, glue, and posterboard for the Extend section, if completed in class.

Key Vocabulary

Chattel slavery - the enslaving and owning of human beings and their offspring as property, able to be bought, sold, and forced to work without wages

Due Process of Law - fair treatment through the regular judicial system, especially as a citizen's entitlement.

Extra-Judicial Violence - using force or harm outside of the legal system, like when someone takes the law into their own hands instead of relying on the courts or police; sometimes described as vigilantism or vigilante violence

Lyceum - an institution for popular education providing discussions, lectures, concerts, etc.

Mob Law - The rule of the mob or the disorderly classes; violent usurpation of authority by the rabble; lynch-law

Mob Violence – when a large group of people acts aggressively or violently together, often causing harm, damaging property, or engaging in destructive behavior due to strong emotions like anger or frustration

Perpetuation – the continued existence or maintenance of something over time

Political Institutions – the organized structures and systems that help make and enforce rules and decisions in a community or country, like governments, courts, and elected offices

Rule of Law - the principle that everyone, including leaders and citizens, must follow the same set of fair and consistent rules to ensure justice and order in a society

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tips:

New American History Learning Resources may be adapted to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in partners or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs or Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge.

These Learning Resources are a collaboration between New American History, the Lincoln Presidential Foundation, and Every Museum a Civic Museum.

Introduction to Lincoln’s Lyceum Address:

These resources are based on a close reading of Abraham Lincoln’s first public speech, delivered in 1838 to the young men of Springfield, Illinois. It is known as his Lyceum Address because it was given in the forum of the Springfield Lyceum, which was one of many across the United States at the time. The Lyceum movement was a 19th-century educational and cultural phenomenon in the United States that featured public lectures, discussions, and adult education programs aimed at promoting lifelong learning, intellectual development, and civic discourse. It was considered an important tool to cultivate an educated citizenry.

Lincoln’s speech reflects his profound concerns about the future of American democracy and his proposed solutions to fortify it. Lincoln emphasizes the importance of preserving the Union and the rule of law, warning against the dangers of mob rule and the potential rise of a tyrant. He urges citizens, especially the youth, to uphold the principles of liberty and equality while actively participating in the democratic process. Lincoln's address serves as a reminder of the responsibilities and vigilance required to maintain a strong and just society, making it a relevant and thought-provoking historical text for students today. The speech also offers valuable insights into Lincoln's early political philosophy and his commitment to the preservation of the United States during a critical period in its history, when the country was moving from the era of the Founders to the leadership of a new generation without direct knowledge of the country’s earliest years. For a further introduction to Abraham Lincoln’s Lyceum Address, read historian Heather Cox Richardson’s short essay in her blog “Letters from an American” or watch historian Doris Kearns Goodwin talk about it in a two-minute clip from a 2018 interview at the National Constitution Center. (These links are also provided in the student-facing introduction.)

The Lincoln Presidential Foundation created a series of three approximately eight-minute films to investigate the history and historical relevance of the Lyceum Address. Each video explores a theme in the speech, highlighting a range of scholars’ thoughts on the speech and Lincoln’s intentions. You can find the video playlist here. (Each video is also linked in the body of the resources.)

Resource Overview:

- Encounter primary and secondary sources that illustrate differing perspectives/points of view on mob violence from the 1830s, and connect them to the young country’s tensions over the continuation and expansion of chattel slavery and continued westward expansion by white settlers into what is now the midwest and was then the western frontier (These sources describe episodes of horrific historical violence in both words and images, and you may wish to prepare students and their adults before they encounter them.)

- Consider what citizens must do to perpetuate (or keep) our democratic republic

- Participate in a Socratic Dialogue that explores the big questions that Lincoln addressed in his speech and that remain relevant today

- Create a museum exhibition exploring moments the country has re-committed to its democratic principles

The Engage section of the resource introduces students to a portion of the Lyceum speech (or a version rewritten for their Lexile, if you prefer) and asks them to imagine connections to present-day issues, including an introduction to the Lincoln Presidential Foundation video series that should help them to understand it.

In the Explore section, students will encounter and use a variety of tools to analyze secondary and primary images that bring to life some of the historical events that Lincoln references in his speech. The See, Think, Wonder strategy provides a framework for students to explore primary and secondary sources from multiple perspectives, and it is especially useful with visual images.

In the Explain section, students will read a passage from Lincoln’s speech and then dig into more challenging primary and secondary sources from the past that ask them to consider the Points of View of the people involved in mob violence and those who opposed them. You can decide whether your students should encounter the texts in their original form or would benefit from reading a transcription. (If you think the vocabulary is too difficult, you might run the transcript text through Chat GPT and ask it to rewrite the speech at your students’ reading Lexile. Make sure that they have access to the original regardless of whether they use it because it might spark curiosity!) Students will use the SOAPSTone strategy to analyze the compositional elements of their primary and secondary sources. SOAPSTone (Speaker, Occasion, Audience, Purpose, Subject, Tone) is an acronym for a series of questions that students must first ask themselves, and then answer, to make meaning out of a text. After analysis, they’ll come back together to share the resources using a method determined through a Choice Board.

The Elaborate section invites the reader to engage with a paragraph from Lincoln’s speech that predicts what could happen in a society where Mob Rule is in place and then respond to reflection questions in writing. Next, students will discuss a big question raised in Lincoln’s speech using the Socratic Dialogue strategy, designed to get students to discuss difficult and abstract themes by linking them to concrete experiences and historical ideas. The Socratic Dialogue Teacher Guide will walk you through setting up a Dialogue in your classroom.

In the Extend section, we encourage you to take the learning further by connecting the ideas raised in this resource to other moments in U.S. history. Using a project-based learning approach, the Classroom Museum Exhibits strategy provides students with ways to work together to create a public-facing product for a specific audience. It can include students working together to coordinate their projects and make sure they are telling all stories or working completely independently, depending upon the learning goals. It gives their research a “real-life” audience and asks them to think about how best to convey what they have learned to real people. This project could be taken on over the course of a semester, spending a bit of time every week working on it. You can learn more about this project here, in a PBLWorks Product Toolkit: Museum Exhibit.

This Learning Resource follows a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience, or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

Read for Understanding (student version)

The Jacksonian era, 1820-1845, was a time of rapid change in the United States. Westward expansion by white settlers, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, and expanding slavery coincided with establishing the Rule of Law in these formerly tribal-held lands and challenged the ideas on which the United States was founded. Abraham Lincoln was a young man during this time, and he was living in Illinois, which was then considered the western frontier. Investigating Lincoln’s first public speech in 1838, which we call his Lyceum Address, can help us understand this period of transition in U.S. history and make connections to questions we are still asking in the 21st century.

Engage:

How might we use current technologies to help us understand the past without losing the author's voice in our primary source documents?

Have you ever thought about why and how we live by a set of rules - or laws - that we agree upon? This learning resource digs deep into the very first speech Abraham Lincoln delivered and asks big questions about how we govern ourselves and how we do or don’t recommit to the ideals of the Revolution and the early Republic. Because Lincoln’s speech was delivered in 1838 - almost 200 years ago - and because he was addressing big ideas, reading and understanding the speech is HARD WORK for our 21st-century brains. It’s worthwhile to spend time with it, though, because the ideas continue to resonate even today. To make the speech more accessible, we have used AI to rewrite the speech for a present-day reader.

Start by reading the first two paragraphs of the Lyceum speech. Remember that there are two versions of the speech in the document: one in Lincoln’s words and one rewritten for a contemporary audience. (You can read the full speech rewritten for today here and read the original words here.) Consider the following questions, and discuss them with classmates, either in person or via chat.

- How does reading the speech in 21st-century English change your understanding of the original paragraphs?

- What understanding and meaning might be lost if you only read the paragraphs in their 21st-century rewriting?

- What might you lose or gain by reading an old speech by a famous leader using ChatGPT?

Learn more about the context of Lincoln’s Lyceum Address by watching the video Fortifying Democracy, Part 1. The scholars in the video represent historians, political scientists, and scholars of rhetoric.

In the video, Dr. Saladin Ambar describes Lincoln’s speech as “profoundly prophetic,” meaning that it predicted what would happen in the future. Turn and talk, or add to a chat: How might the words we read today resonate with the political situation in our own time?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

How might we better understand what motivates acts of mob violence, and how might that inform how we prevent it?

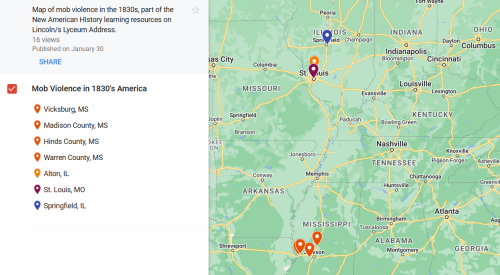

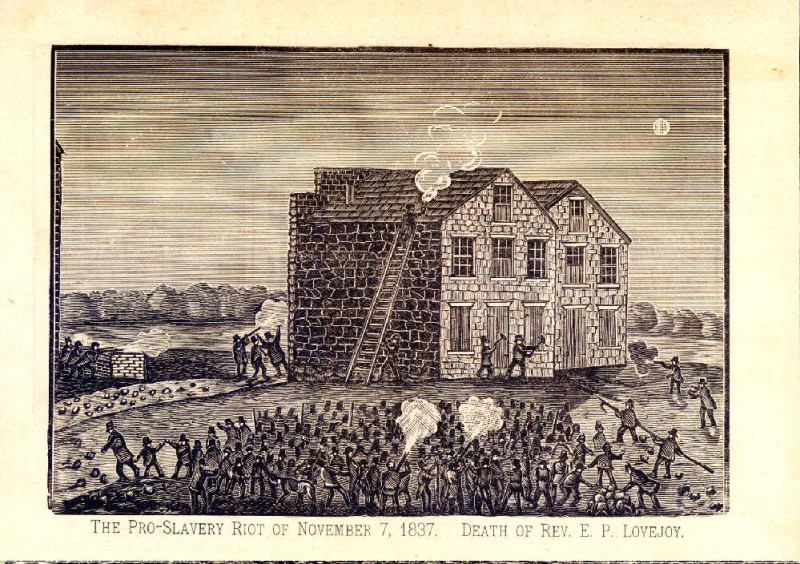

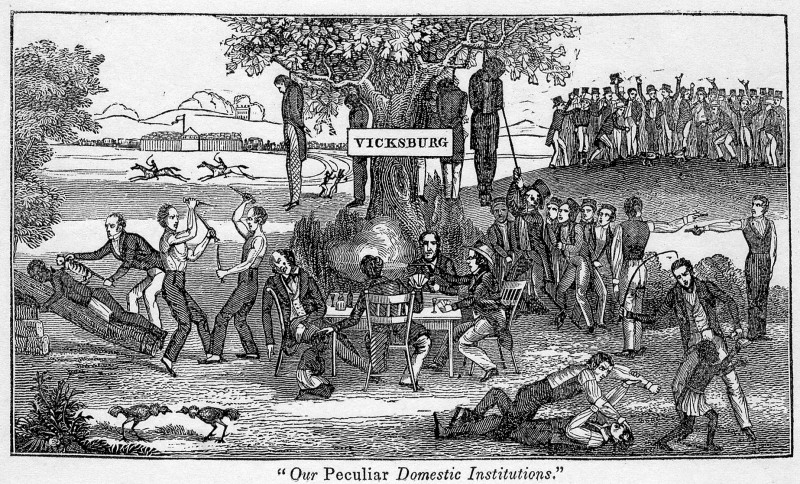

In Lincoln’s speech, he refers to three instances of mob violence that had taken place in recent years in what were then the western states of Illinois, Missouri, and Mississippi. (Can you imagine a time when the mid-west and mid-south were considered the western frontier?) Use the See Think Wonder graphic organizer to explore this map and images.

(WARNING: MAP AND IMAGES MAY CONTAIN GRAPHIC IMAGES OF RACIAL VIOLENCE - PLEASE USE CAUTION.)

Share your See, Think, Wonder observations with the rest of the class, or turn and talk with a classmate. If you are learning remotely, your teacher may allow you to use this Google Slides template as a collaboration tool (make a copy of the template for yourself).

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

What might cause people to opt for mob rule over the rule of law? How does Lincoln suggest Americans respond?

As European settlers moved west into what is now the mid-west and mid-south, they were building new communities made up of people who had a range of ideas about the value of the Rule of Law. Disagreements about the expansion of chattel slavery into the western settlements and the displacement of indigenous nations created a lot of disagreement and tension for the settlers, in addition to trying to transplant the ideas of the Revolution and the Constitution into new lands.

To learn more about some examples of Mob Rule - where people threw off the yoke of the Rule of Law and decided to take it into their own hands - watch Fortifying Our Democracy, Part 2. You’ll also learn what Abraham Lincoln thought about Mob Rule.

Then read this excerpt from Lincoln’s speech and use the First, Then, Finally organizer to make sense of the passage. Follow the Reflect and Discuss prompts (both in the First, Then, Finally slides and also below) to make meaning of his words.

Reflect and Discuss

- What is Lincoln suggesting in the last sentence of the paragraph? What risk worries him if mobs and their passions rule? What does he mean by “walls”?

- What Lincoln is describing is the opposite of the Rule of Law. What do we mean by the Rule of Law v. the Rule of Mob? What might cause people to opt for mob rule?

Next, as you look at the sources below, make sure to take into consideration the Points of View that the source represents. Why might different groups of people have differing perspectives on these events that seem so clearly wrong to us today? Consider geography and date of publication, among other factors, as you examine each source. Also, consider if it is a primary or secondary source. How do you decide?

These sources describe in words and images terrible things that people did to other humans in the 1830s. Do we still encounter things like this today?

After completing the graphic organizer, decide on a primary source to share with the rest of the class to explain what happened.

Primary and Secondary Sources

Elijah Lovejoy Murder, Alton, IL

- 1948 St. Louis Star & Times Essay: Lovejoy, Who Died at Alton, Martyr for Press Freedom (Transcription here)

Francis McIntosh Lynching, St. Louis, MO

- Lynching of Francis McIntosh Digital Exhibit

- Account and Defense of Mob Actions, in National Banner and Nashville Whig, May 11, 1836 (Transcript Here)

Vicksburg, MS, Lynchings

- Vicksburg Letter in Defense of Citizen Actions, August 1, 1835 [reprinted in the United States Gazette, Philadelphia] (Transcript Here)

- Commentary on Vicksburg from The Liberator, Boston, August 8, 1835 (Transcript Here)

Use this choice board to determine which kind of presentation you want to do. Each presentation will focus on three themes:

- Describe what happened, from the perspective of the person or people who were attacked, and from the perspective of the people who were attacking others.

- Emphasize: Why did the mob think it needed to act beyond the rule of law?

- Explain: The different points of view expressed by the people who created the source and why they might have taken that perspective on the event

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

Can people far removed from an event like the American Revolution fully appreciate what it takes to keep a republic? How might we evoke the commitment of the Founding Era in people today?

In this section, you’ll learn more about the Lyceum address with the third Fortifying our Democracy video, focusing on Lincoln’s advocacy for the Rule of Law and his warning about the possibility of a tyrant coming to power if the Rule of Law is not followed.

Then, you’ll dig into Lincoln’s own words (or a version of the speech adapted for your reading level), using the following questions to guide your discussion.

As you watch Fortifying Democracy, Part 3, consider these questions:

- What does Lincoln suggest about the risk and hope of democracy, the farther we get from the country’s founding?

- As the United States approaches the 250th anniversary of its founding in 2026, what risks are we facing, and how might these be connected to Lincoln’s predictions and his recommendations?”

Use your responses to elaborate using a reflective journal entry.

- How, if at all, are Lincoln’s words still relevant today? How does the tension between passion and reason still play out in our political institutions? Give at least one concrete example.

Participate in a Socratic Dialogue with your classmates in response to one of these two questions.

- What is the value of the Rule of Law? Are there times when might it not be useful?

- Does it get harder to hold a democratic republic together the farther we get from the founding generation?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

Have there been moments of change or reimagination so profound that they count as “re-founding” in U.S. history?

In his biography of Martin Luther King, Jr., Jonathan Eig wrote, “On December 5, 1955, a young Black man became one of America’s founding fathers. He was twenty-six years old and knew the role he was taking carried a potential death penalty.”

Think about what you know of the history of the United States. Identify an example of when the country has needed to recommit to its original principles – perhaps we can describe this as a “re-founding.” (Some of these might be instances of Constitutional amendment, but others might be times or events when big changes happened - perhaps through Supreme Court decisions. Let students make their own case.) Create a tabletop exhibition, using at least three primary source images, documents, or recordings, that argue that an event or moment in U.S. history constitutes a “re-founding” and re-commitment at a particular moment in U.S. history or by a particular figure in U.S. History. You can find more information about creating an exhibition here, in a toolkit from PBLWorks.

We would love to see images of your exhibits! Feel free to share them with us either through your school's social media account (if your school permits) or via email: editor@newamericanhistory.org

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

American Anti-Slavery Almanac. “Illustrations of the American anti-slavery almanac for 1840.” New York, New York. United States New York, 1840. New York. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007680126/.

American Anti-Slavery Society. “Particulars of the massacre,” Emancipator Extra. December 1, 1837. https://newseumed.org/tools/artifact/emancipator-details-fatal-shooting-elijah-lovejoy.

Basler, Roy, ed. “Lyceum Address,” The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 1. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln1. Accessed February 7, 2024.

Bouie, Jamelle. “If Destruction Be Our Lot, We Muse Ourselves Be Its Author and Finisher,” New York Times. February 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/03/opinion/abraham-lincoln-ambition-speech.html?unlocked_article_code=1.Tk0.Xlze.dfKFWrkMstIA&bgrp=g&smid=url-share. Accessed February 5, 2024.

Charleston Daily Courier, The. “From the Vicksburg Register,” The Charleston Daily Courier. Charleston, SC. July 28, 1835. https://www.newspapers.com/image/604393030. (Subscription required.)

Eaton, Foster. “Lovejoy, who died at Alton, a martyr for press freedom,” St. Louis Star & Times. St. Louis, MO. June 11, 1948. https://www.newspapers.com/image/205513811. (Subscription required.)

Eig, Jonathan. King: A Life. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2023.

Liberator, The. “Postscript from the Natchez Courier, July 10,” The Liberator, Boston. Boston, MA. August 8, 1835. https://www.newspapers.com/image/34584443. (Subscription required.)

Lincoln Presidential Foundation. 2023. "Fortifying our democracy: Lincoln’s Lyceum Address." Video Series. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLR5Dwi_NdBZGhM7l1EAsoMOZk-xmLTbWK.

McNamara, Robert. "American Lyceum Movement." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/american-lyceum-movement-1773297 (accessed January 23, 2024).

National Banner and Nashville Whig. “Horrible tragedy,” National Banner and Nashville Whig, Nashville, TN. May 11, 1836. https://www.newspapers.com/image/603851488. (Subscription required.)

National Constitution Center. 2018. “Doris Kearns Goodwin explains Lincoln’s Lyceum Address.” Video Interview. YouTube. https://youtu.be/M1LWKm_z_go?si=1y5kGc2KO9msi5Tt.

Norton, W.T., publisher. “The pro-slavery riot of November 7, 1837, Alton, Ill. Death of Rev. E.P. Lovejoy,” 1909 postcard from a woodcut made in 1838. Robert Langmuir African-American Photograph Collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University Libraries. https://digital.library.emory.edu/catalog/535t76hdtx-cor.

Reparative Justice Coalition of St. Louis. “The lynching of Francis McIntosh,” Reparative Justice Coalition of St. Louis, 2022. https://www.rjcstl.org/francis-mcintosh-remembrance.

Reparative Justice Coalition of St. Louis. "Mob violence and racial terror: the lynching of Francis McIntosh." University of Missouri - St. Louis Digital Humanities Lab, 2020-2022. https://www.umsldigitalhumanities.org/francismcintosh/s/francismcintosh/page/introduction.

Richardson, Heather Cox. “Letters from an American,” January 27, 2024. https://heathercoxrichardson.substack.com/p/january-27-2024 (Accessed January 28, 2024.)

United States Gazette, The. “The Vicksburg tragedy,” The United States Gazette, Philadelphia. August 1, 1835. https://www.newspapers.com/image/605024090. (Subscription required.)

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc