This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Lines in the Sand - The Alamo

Read for Understanding:

Some of us have heard the phrase, "Remember the Alamo!" as a Jeopardy quiz show question, or from playing video games. Most Americans living outside of Texas remember very little about the Alamo, except that it was a fort. Some people living in Texas, including a variety of culture groups, historians, and policymakers, continue to debate how to tell that story. They are not alone.

Key Vocabulary

Alamo - originally Misión San Antonio de Valero, a historic Spanish mission and fortress compound founded in the 18th century by Roman Catholic missionaries in what is now San Antonio, Texas

Ambition - a goal for success, a desire to achieve an accomplishment

Anglo-American - white, English-speaking American as distinct from a Hispanic American

Acculturation -when immigrant populations take on enough of the values, attitudes, and customs of the receiving society to function economically and socially (per AP College Board)

Adaptation - characteristic of a living thing that helps it survive in its environment

Amnesia - partial or complete loss of memory as a result of an injury to the brain, illness, or shock

Archaeology - the study of human activity by discovering and analyzing artifacts, or evidence of material culture

Assimilation - a loss of all or many cultural characteristics which make newcomers different

Buffer zone - the neutral zone between two or more areas, creating a separation

Centralize - to bring things that are in different places together at a single point or hub

Clan - a group of people from the same family

Colony/colonization - a group of people from one country who build a settlement in another territory, or land

Conservator - an adult who has legal rights and responsibilities to act as a parent for a child, or primary caregiver

Converted - a person who has been convinced to change to a different belief, religion, view, or political party

Counter-mapping - geographical mapping practices centering on marginalized groups and cultures that challenge the way people see history and the present day

Curator - one who prepares exhibits at a cultural heritage site (gallery, museum, library, or archive)

Descendant - a person related to ancestors

Doctrine - a core belief or set of beliefs associated with a religion or political system

Economics - the study of how goods and services are produced and distributed

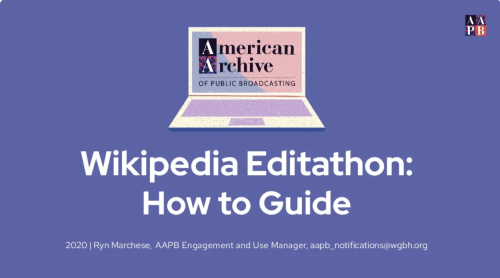

Edit-a-Thon - an event where editors of online communities such as Wikipedia, OpenStreetMap (also as a "Map-A-Thon"), and LocalWiki edit and improve a specific topic or type of content

Empire - a group of nations or peoples under one ruler or government

Excavate - to uncover by digging

Expedition - a journey taken for adventure or exploration

Faulty - damaged, flawed, or imperfect, not working correctly

Flash point - a critical situation or area having the potential of erupting in sudden violence

Franciscan - a member of one of the Roman Catholic orders founded by St. Francis of Assisi

Historical Memory - the narratives that shape people’s understanding of the past, separate and apart from the way scholars depict it.

Historiography - the study of the ways in which history has been documented

Hostile - unfriendly, harsh, argumentative, or showing extreme dislike

Hunter-gatherers - a human living a lifestyle in which food is obtained by foraging (gathering edible wild plants) and hunting

Indigenous - native people, plants, or other elements produced, living, or existing in a particular region or environment

In-migration - the process of people moving into a new area in their country

Insurgents - members of a group who rebel against power structures and government policies

Jesuits - a Roman Catholic order of priests who do mission work

Making camp - creating a place to live temporarily outdoors

Mission - the buildings and land used by a religious order or volunteers to perform charitable work and share religious teachings to convert new believers

Missionary - a member of a religious order or volunteer who performs charitable work or shares religious teachings to convert new believers

Mythology - traditional stories passed down within a specific culture

Out-migration - the process of people moving out of an area in their country to live in another area in their country

Parish - a district of a Christian religion that has its own church and priest or minister.

Perseverance - to continue an action, task, or belief with dedication

Plains - a large, flat area of land with few or no trees, sometimes covered by long grass

Plea - a serious or sincere call for help; an appeal

Passive - offering no resistance or reaction

Quinceaneras - a celebration of a girl's fifteenth birthday that is traditionally observed in Mexico and Latin American cultures as a transition to adulthood

Quintessentially - representing a perfect or typical example of something

Revisionist history - the reinterpretation of a historical account

Silt - fine particles of earth, clay, or sand that eventually settle out of water

Spur - urge someone to take action with greater effort or speed.

Subjects -people ruled by a leader or by a state

Tejano - descendants of the first Spanish, Mexican, and indigenous families on the Texas frontier

Territory - an area or region of land that belongs to and is governed by a country

Texians - Anglo-American residents of Mexican Texas and, later, the Republic of Texas

Thriving - well and strong, successful

Ward - an administrative designation for a sub-area of a city or county

Engage:

Where does Texas history begin?

Many generations of Americans grew up with a stereotypical image of cowboys as “the good guys” in hats and boots who rescued women and children. This image is reinforced by pop culture icons from the Lone Ranger to Woody from Toy Story. Textbooks in some states have been slow to reflect changes to this narrative, instead of reinforcing stereotypes and telling the story of the American West through a purely Anglo-American lens. Historian Ed Ayers set out to find out the real story behind some of the most widely held misconceptions about the West and the Alamo. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Introduction: Where does Texas history begin?”).

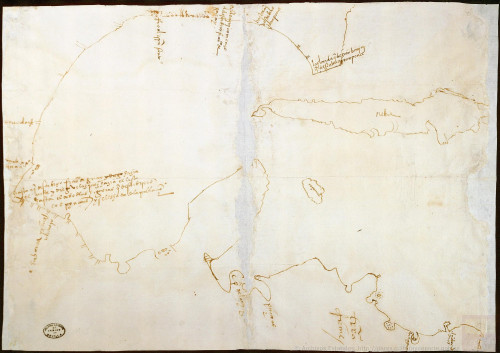

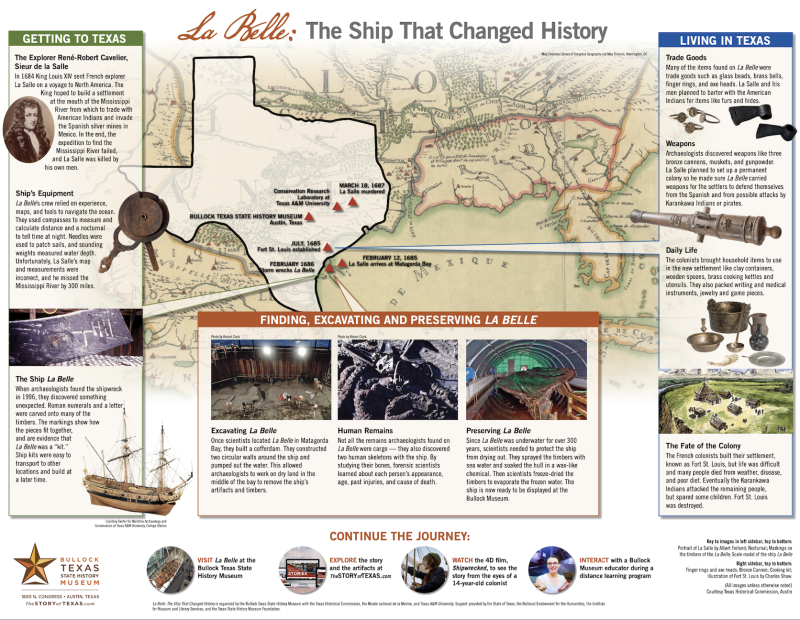

Much of the story of Texas history is told in movies, television shows, and textbooks from the perspectives of the white American settlers who moved west into Spanish territories, clashing with both Mexicans and Indigenous people over land and the expansion of slavery. What is not widely shared are the French roots in Texas’ history, from the Age of Exploration to the wonders of modern archaeology. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "The Secrets of a Shipwreck”).

Take a few minutes to explore the artifacts from this virtual exhibit and the La Belle Shipwreck poster/map from the Bullock Texas State History Museum. (Note: the poster is best viewed on the website.)

Turn and talk to an elbow partner to answer the questions below about this image. If working remotely, your teacher may let you work using a collaborative document such as Google Docs or Google Slides.

- Describe the process archaeologists used to preserve the boat.

- What was the most surprising discovery you explored in the exhibit or on the map?

- How would you describe the role the French played in the early history of the region?

- What did you learn about the Karankawa?

- Why might Texas history be more closely associated with only its Spanish roots?

- What questions do you still have about the Karankawa or the La Belle?

- Where might you locate the answers to your questions?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

Why has the story of Texas’ origins obscured the role of Indigenous peoples and the Tejanos, and how is that narrative changing?

The story of the La Belle illustrates the role of the early French explorations of the region, long overshadowed by those of the Spanish empire. To tell the full story of Texas history it is essential to include the contributions of centuries of Indigenous peoples who inhabited the region before European contact and conflict.

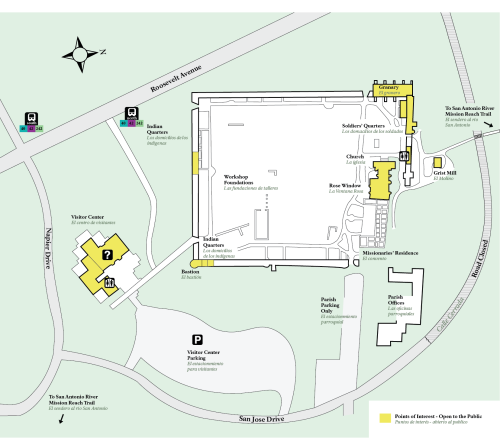

Their stories are intertwined with those of the early Spanish missions. Historian Ed Ayers visited Jorge Hernández, a guide with the National Park Service at Mission San Jose.

(View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Spanish Missions in Indian Country.”)

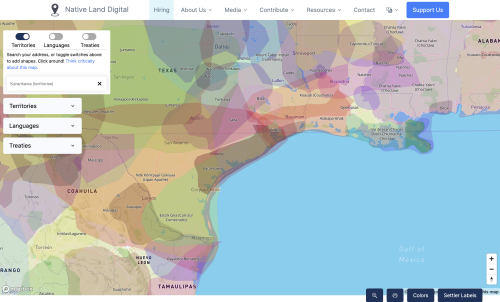

The native-land.ca map is an example of counter-mapping, exploring, and representing the Indigenous peoples who inhabited the land. This crowd-sourced map includes interactive layers representing territories, language groups, treaties, and European settlements. Take a few minutes to explore the map, taking note of the Indigenous hunter-gatherer populations that lived in the area now known as Texas.

Turn and talk to an elbow partner to answer the questions below about this image. If working remotely, your teacher may let you work using a collaborative document such as Google Docs or Google Slides.

- What do you notice?

- How is this map different from some of the other maps you have used in school or on your own?

- Who were some of the early culture groups represented on the map that were new to you?

- What did you find most interesting about these groups?

- What questions do you still have about the map and the culture groups you explored?

- How might the current descendants of these culture groups use the UNESCO World Heritage designation to help tell their stories?

Another group of early Texans has also been left out of much of the story of Texas until more recent years. These early inhabitants were the Tejanos. Tejanos are descendants of the first Spanish, Mexican, and indigenous families on the Texas frontier, and their roots go back to some of the earliest settlements in the late 1600s.

Much of the present-day Tejano culture is rooted in the history of their earliest peoples and the founders of the early Spanish missions. Texas A&M University Associate Professor Armando Alonzo researches the history of Tejanos and the borderlands of Mexico and the United States.

Take a few minutes to explore this interview to learn more about Tejano's history.

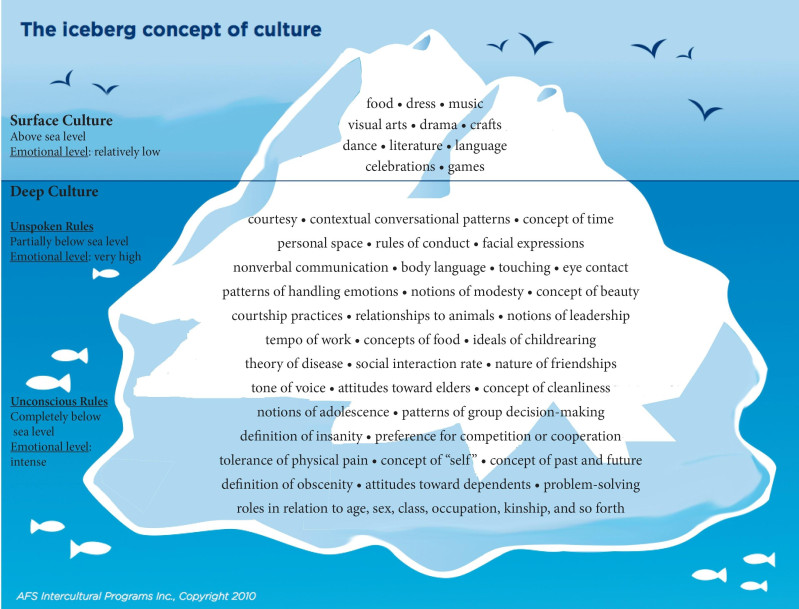

The Iceberg model helps us look beyond stereotypes and simple representations of a culture so we might think more deeply about how all members of a community and their shared pasts better represent the story of a nation. Take a few minutes to explore the first diagram and reflect on your cultural heritage.

Your teacher may provide a blank copy of this graphic organizer to help you process your thoughts and record what you learn about the Tejano as you read the interview, Understanding Tejano History.

If time permits, you may choose to share your reflection on the history and culture of the Tejanos with an elbow partner or work virtually using a collaborative document such as Google Docs or Google Slides.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on the graphic organizer as an exit ticket.

Explain:

How does historical memory differ from generation to generation, and across cultures?

Over 100 Indigenous groups settled into Spanish missions in the 17th and 18th centuries near present-day San Antonio, Texas. The descendants of the people who lived in these missions are working to preserve that history by sharing the stories of their ancestors. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "Keeping Alive Memory of the First Texans.”)

Ramon Vasquez describes these smaller culture groups who resided within the Spanish missions as “bands and clans,” who were seeking safety from larger Indigenous groups such as the Apaches. He says they made a decision to take sides and give up some of their own culture and beliefs for the protection of living in the mission with the Spanish, as more of these settlers poured into their region.

Indigenous groups including the Tilijae, the Ervipiame, the Pakawan, the Paguame, and the Payayas are a few of those who resided within the missions. As more Spanish missions were built, Vasquez explains how those smaller groups sought refuge from warring tribes, many weakened by the diseases brought in from European contacts, and under threat of displacement by the growing population of white settlers. Others resisted, choosing to stay true to their own culture and risk their own survival.

Their stories are not typically included in history textbooks, films, or other media. The Indigenous descendant communities of the Spanish missions are looking to change that narrative.

Explore the descendant communities’ stories in “We’re Still Here: Mission Descendant Stories.”

- What similarities and differences did you find as you explore these stories?

- Who might you share these stories with, and why?

- How might you suggest these stories find a larger audience? Give examples.

As a final reflection, turn and talk to an elbow partner to share your reflections on the following question, using one or more of the descendant narratives you read. If working remotely, your teacher may let you work using a collaborative document such as Google Docs or Google Slides.

- Which story was the most surprising, interesting, or troubling to read? Explain your answer.

Your teacher may choose to provide this graphic organizer to help you organize your answers.

In addition to working hard to ensure their stories are not erased, the mission descendent communities continue to advocate for the respectful acknowledgment of their sacred Native burial grounds. Listen to this report from Texas Public Radio about the reburials at Mission San Juan.

- How have descendants of the Indigenous peoples who were buried at the Alamo engaged in civic efforts to reclaim their ancestors’ remains?

- What specific requests have been made on behalf of the descendant communities?

- How did the state of Texas respond to their requests?

- What might their next steps be moving forward?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

Where does the history of enslaved African-Americans fit into the story of Texas?

Indigenous peoples inhabited present-day Texas long before the French or Spanish arrived, and continued to hold large tracts of land both before and after Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. Despite outlawing slavery in 1829, the Mexican government allowed white slaveholders to immigrate to its newly held territory in Texas, with lasting consequences for all inhabitants of the territory, and their descendants. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "How Slavery Changed Texas Forever.”)

Educator Naomi Carter discusses the shift toward re-envisioning history in Texas surrounding the story of the Alamo, and the expansion of slavery into the Texas territory.

Take a few minutes to explore this Bunk tag to see other topics related to revisionism and revisionist history. You may wish to share an interesting connection you made to this topic related to Texas history or history education in general.

The name Stephen F. Austin has been synonymous with Texas history for decades. But the story of him and his “Old 300” is often told through the lens of the white settlers, rather than the Indigenous populations or the enslaved who were forced to migrate to Texas.

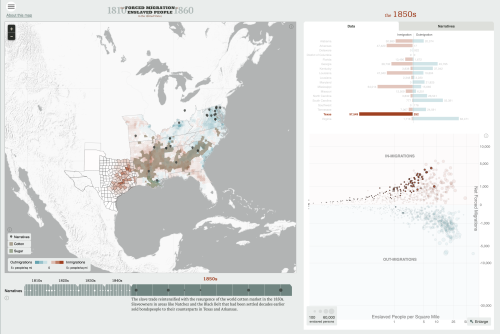

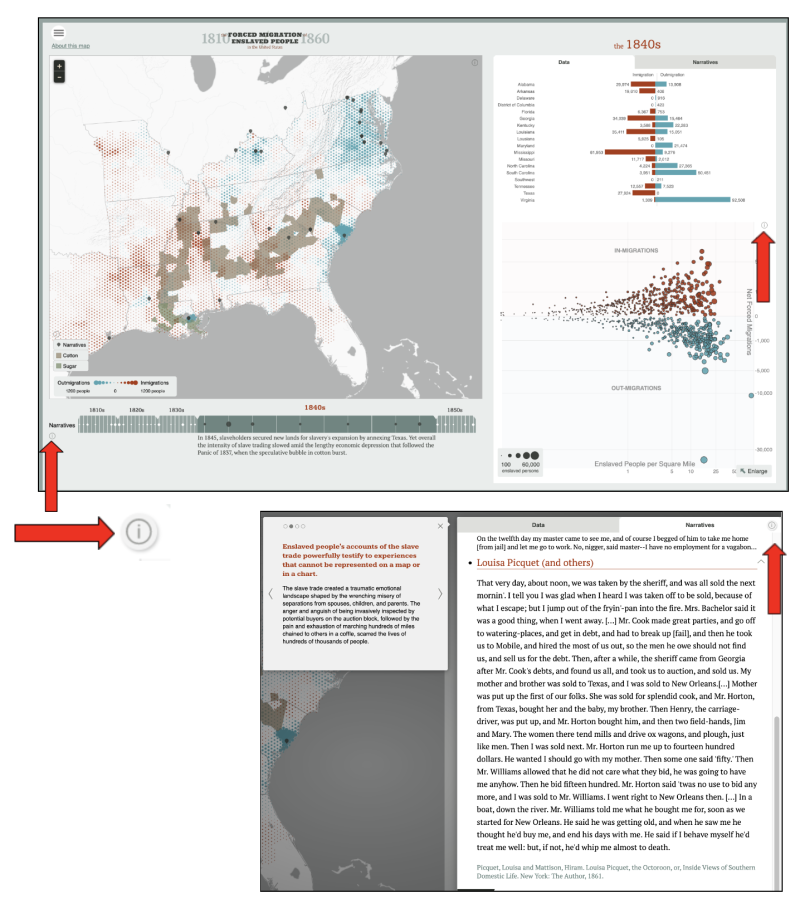

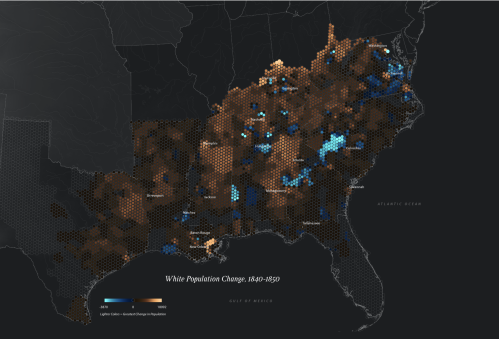

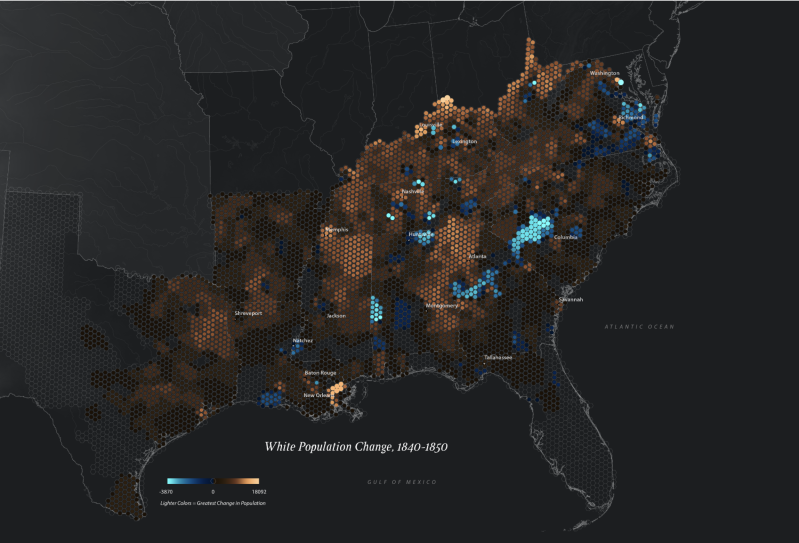

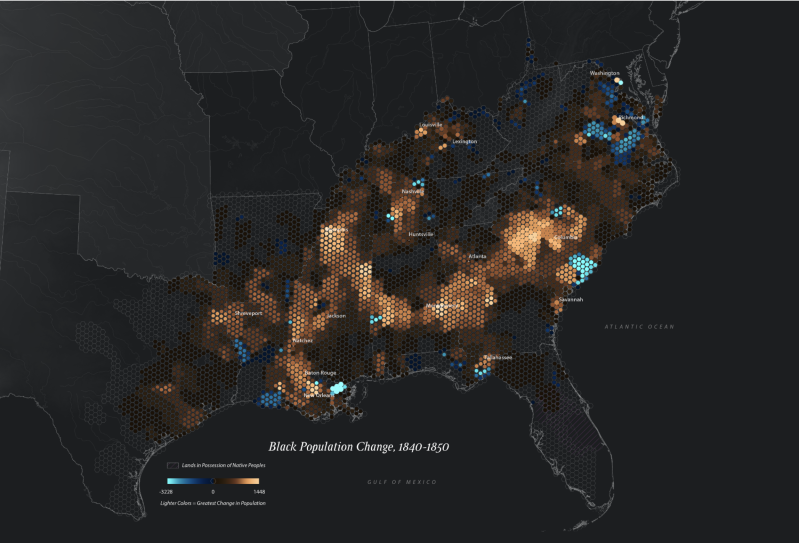

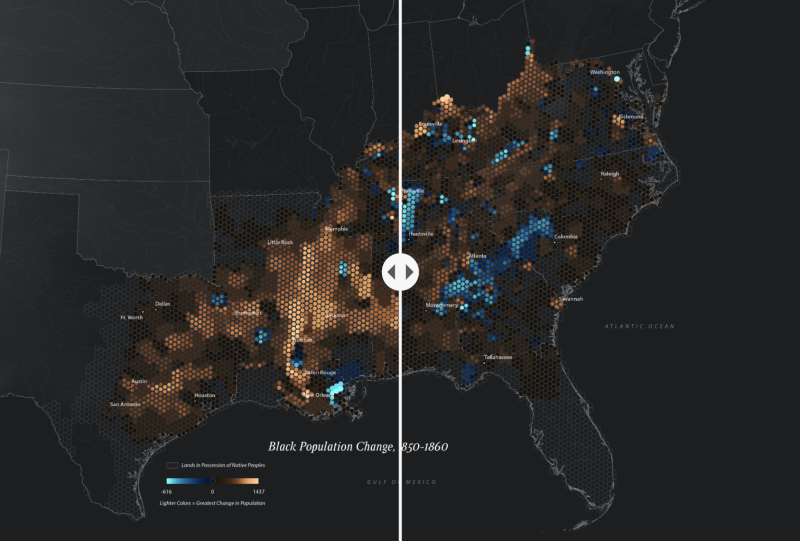

This map of the Forced Migration of Enslaved People in the United States allows you to explore patterns, visualize data and read primary source narratives from 1810 to 1860. Notice Texas does not appear in the data until the 1840s. Take a few minutes to explore the map, including the data found on the right side of the map.

Use the slider tool at the bottom of the map to compare/contrast the data from the 1830s to the 1840s.

You may click on the state of Texas to see specific data by county or select the Narrative tab at the top of the data screen to read primary source narratives of the enslaved. Select each commodity (sugar, cotton) to see how economics drove the forced migration of the enslaved.

Be sure to select the “i” buttons located throughout the map to help you navigate the tools and interpret the map.

Note the use of color on the map to show the out-migration in blue and in-migration in copper indicating the movement of enslaved people.

- What does the data reveal about the out-migration of enslaved African-Americans in the 1840s?

- How is this data related to the sugar and cotton trades?

- How does Louisa Picquet’s story in the narrative from the map change your understanding of Texas history during this time period?

Now let’s compare the migration patterns of both white and Black populations in Texas, using the maps of Southern Journey. This map is presented in a StoryMap format, and you will scroll through several maps, and images and read the text along the way. Like the maps of Forced Migration, the out-migrations are indicated in blue, and in-migrations are shown in copper on each map. You will explore map ONE: Creating the South, 1790-1860.

Navigate to the maps showing white and Black populations, 1830-40 and 1840-50. You will want to view these maps in the StoryMap; the gallery view below is shown here to help you navigate the map. As you continue scrolling, you will see additional related maps on cotton production and other economic and population data related to the enslaved population.

- What patterns do you notice on the maps as you navigate between each decade?

- How do these patterns differ between the white and Black populations in each decade?

- Which of these maps, including Southern Journey and Forced Migration, would you suggest to living history interpreters like Naomi Carrier to best tell the story of Texas history? Explain your answer.

Take a few minutes to skim through these two descriptions of the history of the Varner-Hogg Plantation. One is from an official state government-sponsored website of the Texas Historical Commission, and the other is from a crowdsourced Wikipedia entry.

(Note: Wikipedia is an open online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers through open collaboration and a wiki-based editing system. Individual contributors, also called editors, are known as Wikipedians. Despite some highly publicized problems that have called attention to Wikipedia’s editorial process, Wikipedia is the largest and most-read reference work in history. Over the years many volunteers have worked to improve the accuracy of the site. Caution should be used as with any crowdsourced content, there is room for error.)

- What do you notice about the similarities and differences between both entries?

- Which entry do you think does a better job of telling the story of all people involved in the history of this property, and the state of Texas?

- Which entry best tells the story of the enslaved populations there over time?

- What does each entry tell you about the story the source is trying to tell?

- What is emphasized most about this history in each entry?

- What is missing from each of these entries?

- How might you and other students help correct or improve these narratives?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

Who decides what is taught about the Alamo as part of the bigger story of America?

Historians of American history like Ed Ayers spend most of their time interpreting history, seeking new ways to tell the stories of America based on the most recent scholarship, newer technologies, and new evidence. Like scientists, they are open to new interpretations of the past and seek to tell the most complete and honest narratives based on the documents, artifacts, and material culture available at the time. The story of the Alamo has unfolded for centuries as new information about the people and events who shaped that place have become more widely available. (View segment of The Future of America's Past: "The Alamo, in Truth and Fiction.”)

Competing versions of the story of the Alamo, as seen in the video, are part of a larger discussion about history.

- Why are some peoples’ histories more prominent than others?

- Where does Texas history begin?

- Where does American history begin?

- Are the Texians the “heroes” of this story?

- Is it a simple case of winners and losers?

- What did Texas declaring independence mean for the Old 300 v. the enslaved, Indigenous, and Mexican populations living in Texas?

- How did the word Texan become synonymous with cowboy culture and who is a real cowboy?

For a long time, these questions were answered in history courses and textbooks through an Anglo-American lens. Challenging these narratives, and bringing forth new scholarship includes the stories of others present during the fight for an independent Texas. It includes more than stories of battles and power struggles. It includes the voices of the Indigenous, the enslaved, and the women who helped shape Texas’ origin stories. When included, these make room for new ways to interpret the famous phrase, “Remember the Alamo.”

“What I find is there's a great hunger out there for people for history and it isn't you know, "Tell me the stories that I grew up with,” because we're reaching a period where some people aren't growing up with stories, right? So they're coming here and “What is this place?” And this hunger, it's “Tell me about the past,” and what they're really saying is, “Tell me who I am.”

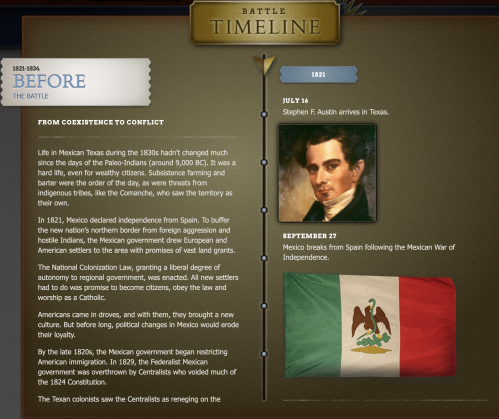

This timeline explores those events. As you read along, think about whose stories are included in the narrative and whose stories are left out. (Select the green Timeline feature to launch the timeline and explore these events).

Skim through this interview, or listen to the audio version to explore more ideas about challenging historical narratives of the Alamo.

- How does the timeline differ from the description of the Battle at the Alamo in the video?

- How does the video contribute to or further confuse the issue?

- How might one decide which version is the “right one”?

- Is there only one “right” version?

In most states, the state Board of Education and the state legislature have jurisdiction over what is taught in public schools. Over the years, parents, teachers, and administrators have had input in this process, usually in the form of public comment, or serving on advisory committees as the state curricula are reviewed or new textbooks are adopted.

In recent years, there has been much discussion and debate across the country about which narratives should be taught. Some states have passed legislation limiting what teachers and students can discuss, or what instructional materials may be used in the classroom. Historians, educators, museum curators, and interpreters have all weighed in on these debates. Meanwhile, students continue to be immersed in history not only in school, but through music, film, television, videogames, and increased access to technology.

Texas is not alone in this discussion and debate. As seen in the video, the “myth of the Alamo” is part of a bigger problem when not everyone is included in the marketplace of stories about America’s past. Take a few minutes to explore this topic by viewing this excerpt in Bunk.

Explore a few related topics in Bunk using the Connection icons to the right of the excerpts, and by selecting the View Connections button below the deck of cards on the right of the screen.

As you flip through some of these connections, you will notice tags in between each connected excerpt. These tags indicate topics the 2 excerpts have in common. You may choose to explore a tag or continue to explore other connections.

- What other topics do you notice are tagged in relation to the original excerpt you read about history textbooks?

- What tags seem to be most frequently related to multiple other connections?

- What tag or tags are you most curious to explore?

- What do these tags have in common as they relate to the textbook issues you explored in the Bunk excerpt?

- Do you have an idea for another related tag you might suggest being added? Explain your thinking.

As the textbooks and curriculum debates continue in the statehouse and the courthouse, some students and teachers are working to move beyond textbooks, turning to open source resources including digital scholarship such as Bunk, or the maps you explored in American Panorama. Others are looking towards museums and other public websites such as the Smithsonian’s Native Knowledge 360° or the National Park Service’s San Antonio Missions National Historical Park to supplement their understanding of history.

Another way to combat this issue is to look for ways to crowdsource and make more complete narratives available to more people, including students and the general public. An Edit-A Thon event is where a group of people collaboratively edit the content on an online community such as Wikipedia. Many Edit-A-Thons have been conducted with the intentional goal of closing the gap in information around marginalized communities or correcting historical narratives. On college campuses, and in museums, public libraries, and some high school classrooms, educators and those who support history and literacy education, art history and science are hosting Wikipedia Edit-A-Thon events to help edit and improve existing content on Wikipedia, or to create content as a way to combat the imbalance of the narratives being represented in each field of study and within the online encyclopedia.

Some are creating more entries amplifying the contributions and discoveries of women in history and science, and underrepresented gender and demographic. Others are creating Wikipedia pages or Islamic-American, African-American, Hispanic/Latin American, Afro-Caribbean, or Asian-American/Pacific Islander history to help balance the largely Eurocentric entries already existing within the site.

Wikipedia has prepared training materials on its site to assist with Edit-A-Thon events.

Consider hosting a Wikipedia Edit-A-Thon event in your school or community, either in person or virtually, You will want to include your school librarian, and consider recruiting local public or postsecondary library/media specialists, local museum archivists, or historical society staff. Additional resources and the use of the planning guide from Wikipedia are essential for the success of your event.

Start small, using a local example from your own community, or perhaps create a very simple entry for a person or historical site in your community that is not currently represented or could benefit from more details to an existing entry.

A cartographic version of an Edit-A-Thon is a “Map-A-Thon”- stay tuned as we hope to explore this option in a future learning resource!

Obviously, we would NOT recommend that every school that is using this learning resource should plan to edit the Alamo Wikipedia page - that would result in too many edits, and most likely send a red flag to Wikipedia to lock the article as a safeguard.

We would love to help you publicize your Edit-A-Thon event! Contact us via email at editor@newamericanhistory.org and let us help you spread the word, participate and share your efforts with others.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

(As noted in an earlier disclaimer, Wikipedia is an open online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers through open collaboration and a wiki-based editing system. Individual contributors, also called editors, are known as Wikipedians. Despite some highly publicized problems that have called attention to Wikipedia’s editorial process, Wikipedia is the largest and most-read reference work in history. Over the years many volunteers have worked to improve the accuracy of the site. Caution should be used as with any crowdsourced content, as there is room for error.)

Citations:

AFS-USA. “The Hidden Ways in Which Culture Differs: AFS-USA.” AFS-USA (American Field Service - US Department of State), February 26, 2022. https://www.afsusa.org/educators/lesson-plans/hidden-ways-culture-differs/.

“Age of Exploration.” The Alamo. The Alamo Trust, Inc., State of Texas, 2022. https://www.thealamo.org/remember/age-of-exploration.

“Bunk Tag: Revisionism.” Bunk History. New American History at the University of Richmond, 2022. https://www.bunkhistory.org/tags/ideas/1297.

(dataset) Native Land Territories map. (2021). Native Land CA. https://native-land.ca/.

Davies, Dave. “'Forget the Alamo' Author Says We Have the Texas Origin Story All Wrong.” NPR Fresh Air. NPR, June 16, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/06/16/1006907140/forget-the-alamo-texas-history-bryan-burrough.

“How to Run an Edit-a-Thon.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, March 12, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:How_to_run_an_edit-a-thon.

Martinez, Norma. “We're Still Here” - 10,000 Years of Native American History Re-Emerges.” Texas Public Radio. Texas Public Radio, January 24, 2020. https://www.tpr.org/san-antonio/2019-03-14/were-still-here-10-000-years-of-native-american-history-re-emerge.

Mercer, Mia. “Understanding Tejano History.” Texas A&M Today. Texas A&M University, October 7, 2021. https://today.tamu.edu/2021/10/07/understanding-tejano-history/.

"S-I-T: Surprising, Interesting, Troubling." Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed July 29, 2020. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/s-i-t-surprising-interesting-troubling.

SOPTV, and Robert Harrison. “Iceberg Concept of Culture Images and PDFs.” PBS LearningMedia. SOPTV, February 10, 2021. https://vpm.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/a353a4ba-cd56-4999-97dd-0e40e11a7211/iceberg-concept-of-culture-images-and-pdfs/.

"The Future Of America's Past: Lines in the Sand." 2019. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com/.

“The Ship La Belle: Bullock Texas State History Museum.” The Ship La Belle. Bullock Texas State History Museum, 2022. https://www.thestoryoftexas.com/la-belle/the-exhibit.

“Vaqueros: The Original Cowboys of Texas.” Texas Highways. Texas Highways Magazine, Texas Department of Transportation, September 7, 2021. https://texashighways.com/culture/people/vaqueros-the-original-cowboys-of-texas/.

“We're Still Here: San Antonio Mission Descendant Stories.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior - San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, March 14, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/saan/learn/historyculture/we-re-still-here-san-antonio-mission-descendant-stories.htm.