This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Lynching in America

View Student Version

Standards

C3 Framework:D2.Civ5.9-12. Evaluate citizens’ and institutions’ effectiveness in addressing social and political problems at the local, state, tribal, national, and/or international levels.D2.Civ.12.9-12. Analyze how people use and challenge local, state, national, and international laws to address a variety of public issues. D2.Civ.13.9-12. Evaluate public policies in terms of intended and unintended outcomes and related consequences.

National Council for Social Studies:Theme: Power, Authority, and GovernanceTheme: Civic Ideals and Practice

National Geography Standards: Standard 17: How to apply geography to interpret the past

Teacher Tip: Think about what students should be able to KNOW, UNDERSTAND, and DO at the conclusion of this learning experience. This activity contains gruesome images and text related to mob violence and lynching. A brief exit pass or other formative assessment may be used to assess student understanding. Setting specific learning targets for the appropriate grade level and content area will increase student success. If students are working remotely, you may provide opportunities for them to collaborate with classmates using video conferencing, access to an online chat feature, or breakout rooms.

Suggested Grade Levels: High School (9-12)

Suggested Timeframe: 3 class sessions, 45 minute class periods

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet, or mobile device; projector and screen for viewing video segments as a whole group if providing face to face instruction.

Key Vocabulary

Anglo (Anglo-American) -a white, English-speaking American as distinct from a Hispanic American

Atrocity - an extremely cruel or shocking act of violence

Cartography - the art, science, and technology of making maps

Grisly - especially horrible or violent

Jim Crow laws - state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in post-Reconstruction America

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) - a white supremacist group founded in 1865 to intimidate African Americans and other minority groups from asserting themselves in any way, including politically

Latinos - a person with Latin American ancestry

Mob - a large, angry group of people, committing acts of violence on a wide scale

Normalize - to create the idea that something previously considered abnormal or unacceptable is standard

Perpetrator - to bring about or carry out, commit an act

Racial terror - the threat or act of violence based on race to intimidate and cause fear in its victims

Restrictive Covenant - contractual agreements that prohibit the purchase, lease, or occupation of a piece of property by a particular group of people, usually African Americans, immigrants, or Jewish people

Souvenir - an object kept as a reminder of a place, person, or event

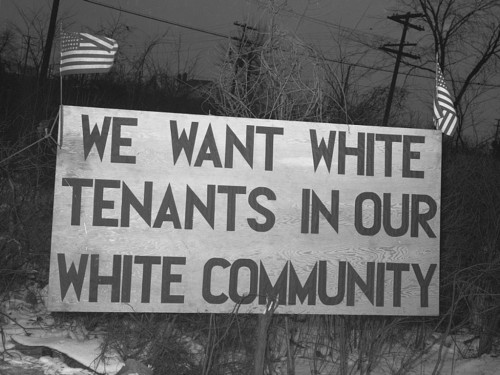

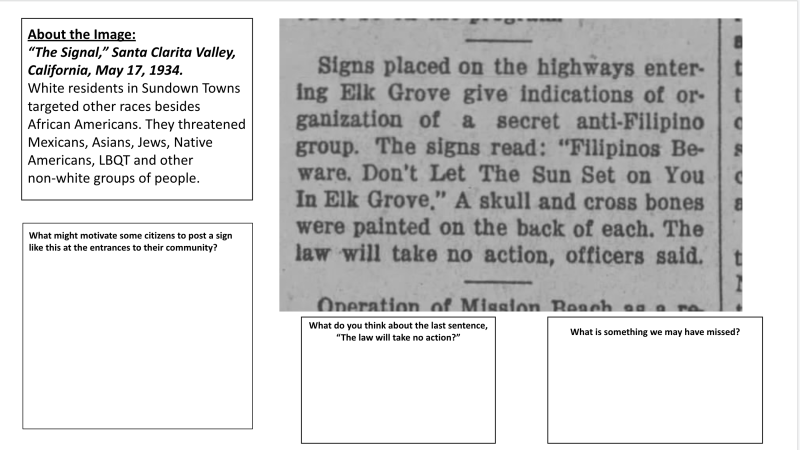

Sundown Towns - a town that is or was purposely all-white. The term came from signs that were posted stating that people of color had to leave the town by sundown. Black people could not visit after sunset or spend the night in the town (even as paying hotel customers). Such towns are also sometimes called “sunset towns” or “gray towns.”

Tabloid - a newspaper characterized by its graphic images, sensationalized headlines, and scandalous topics, often lacking in reliable sources

Vigilantes - citizens who take the law into their own hands, acting outside the criminal justice system

Trophy - an object used as an award for victory or achievement, or an item collected to remember or prove participation in an event, including the commission of a crime

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tips:

This Learning Resource includes language in the body of the text to help adapt to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in partners or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs or Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge.

The Google Slide format used in this learning experience can be modified by moving around the slides, deleting slides, and adding images to the lesson. Images may be modified as needed, and additional image citations are in the Google slides. You will need to make a copy to modify.

Lynching can be explored in further detail through the Equal Justice Initiative’s report, Lynching in America, and by listening to this NPR podcast. Additional content for teacher background knowledge can be found at Without Sanctuary, including a short film narrated by James Allen. (Trigger warning: this site contains graphic images). Further reading on the Chinese Massacre of 1871 is available from the Los Angeles Public Library. A short film to introduce the history of lynching to students is available at Facing History and used in this Learning Resource. Transcripts are available for classroom use. (Note: Facing History no longer allows their videos to be displayed directly on other sites, use caution when sharing this link in class as we are not able to filter out other videos, comments, etc.).

This Learning Resource uses “Thinking Routines” from Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education that has developed learning strategies that encourage students to add complexity to their thought processes. For an overview of Project Zero’s methodology, you may want to read its Exploring Complexity Bundle. Specifically for this lesson, students will use the See, Think, Wonder thinking routine.

Additional instructional strategies used include Turn and Talk (elbow partners) for collaboration and Facing History’s S-I-T (Surprising, Interesting, Troubling) protocol. Bunk Collections, groups of Bunk excerpts that share a common topic or theme, are also used to further explore the history of lynching.

These Learning Resources follow a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience, or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

For Students:

This lesson focuses on a tough subject: the history of racial terror and violence in the United States. It looks at the geography of the violence and commemoration as well. Your teacher may provide images to you using a collaborative document such as Google Slides. Your teacher will provide a link to the slides, or ask you to make a copy of the slides in this lesson. You will be able to respond on some of the slide text boxes, or as directed by your teacher.

Engage:

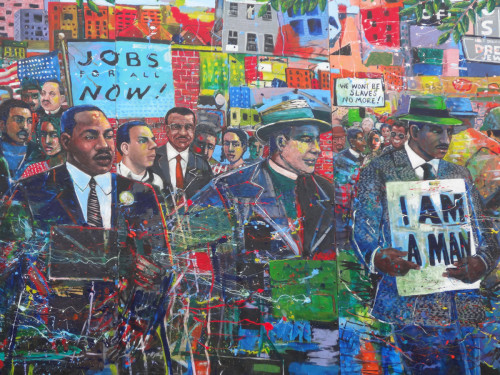

Why do people participate in acts of racial terror or violence?

This era of American history will be challenging yet informative for you as a student to read, hear and reflect about as you continue on your educational journey. Your family and community members should be partners and included in supporting your learning about history, alongside your classmates and teachers. Your teacher may determine that some images and portions of this learning resource may be too sensitive for you or some of your classmates to explore. Always check in with your teacher if you have questions or need additional guidance as you learn about challenging topics in history. As needed, your teacher may provide additional or supplemental resources to substitute for some learning experiences, while still helping you develop empathy as a learner.

The origins of the term “lynching” date back to the American Revolutionary War era, most likely to a Virginia judge, Charles Lynch, who used harsh sentences to punish Loyalists. It came to refer to violent acts including hangings, beatings, dismemberment, and mutilation that resulted in death.

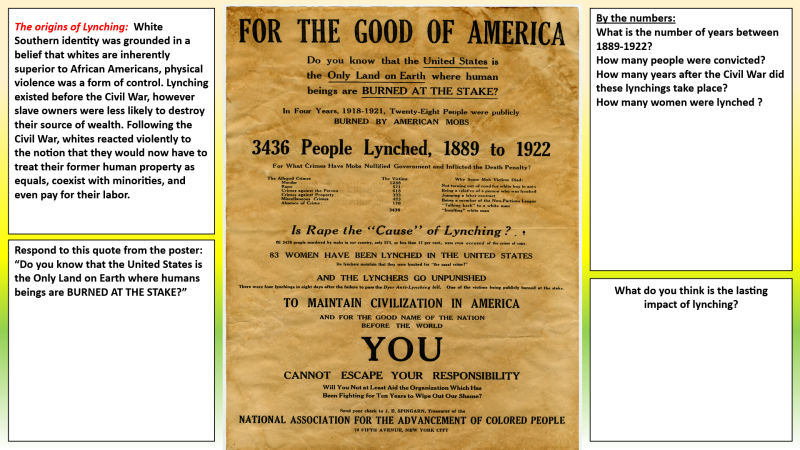

Lynching became a more widely practiced violent form of vigilante justice after the Civil War. Between the Reconstruction period and the Civil Rights Era, murderous acts by white mobs became a common occurrence in America. These acts of violence were seen as justice by men who believed in their superiority over racial and ethnic minorities. You can learn more about lynching in this short film from Facing History.

To learn more about the origins of the lynching, explore slide number 2. Read the poster For the Good of America and answer the questions in each square text box. (Note: The language on the poster may be offensive to some readers. Your teacher will discuss if it is appropriate for you to view or perhaps offer an alternative image as needed.)

The Rise in Black Prominence

Although the practice of lynching preceded the end of slavery, it became more prevalent in the United States during Reconstruction, when African Americans across the South began to make political and economic gains by registering to vote, establishing businesses, and running for public office. Many white people, including former Confederate soldiers, landowners, businessmen, and poor whites were threatened by this rise in black prominence. In particular, there was a fear of sex and procreation (having children) between the races. Some whites supported the idea that black men were sexual predators and wanted integration in order to be with white women. At this time, interracial marriage was illegal in many parts of the country. Their fears escalated the violence in towns across America during this era.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on the slide or as an exit ticket.

Explore:

Who were the victims and perpetrators of mob violence in 19th century America?

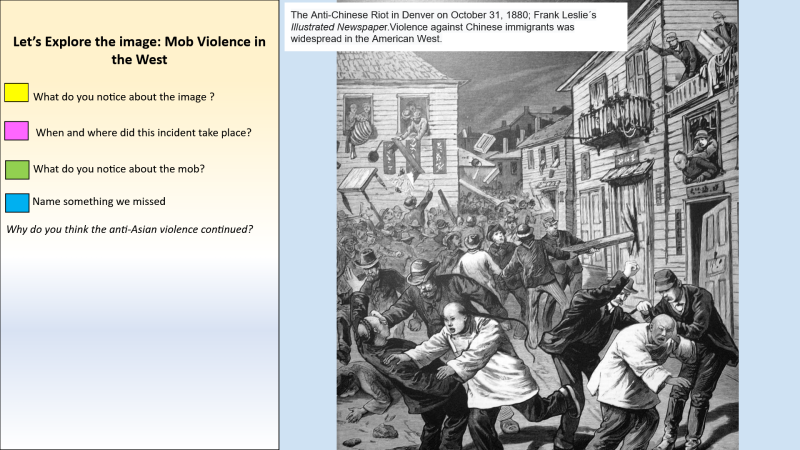

Racial, ethnic, and religious minorities were most often the victims of mob violence. In California, Chinese immigrants were victims of some of the largest atrocities. One was the lynching of 19 Chinese-born men and boys in Los Angeles on October 24, 1871. The incident was considered retaliation for the death of a white man caught in the middle of a firearm dispute between two Chinese immigrants. Learn more in this PBS video: “Lost LA-The Chinese Massacre.”

Use slide number 3 to examine an image of another incident of anti-Asian violence that occurred 9 years later in Denver, Colorado. Use the text box on your copy to respond to each question.

Think about the video you watched and the images you analyzed to answer the following questions. Turn and talk to an elbow partner, or if working remotely your teacher may allow you to use a collaborative document or discuss via videoconferencing.

- Why did the Chinese migrate to the areas with the Black settlers?

- Do you think they were made to feel welcome in American communities?

- Did it surprise you that the Chinese population continued to grow despite the violence?

- What details from the video or images you analyzed might explain this growth?

Why did everyday Americans turn to such violent acts of racial terror? The loss of labor from the formerly enslaved population was a hardship to the southern plantation owners’ crop production and wealth. After losing their labor force and the ability to gain wealth via the slave trade, many believed they had been wronged and should be compensated. Racial terror, including lynching, was a tool used to enforce Jim Crow laws and racial segregation. White elites attempted to maintain control by terrorizing Black citizens for minor social transgressions or for demanding basic rights and fair treatment. White people were typically not convicted of murder for lynching a Black person in America during this time period.

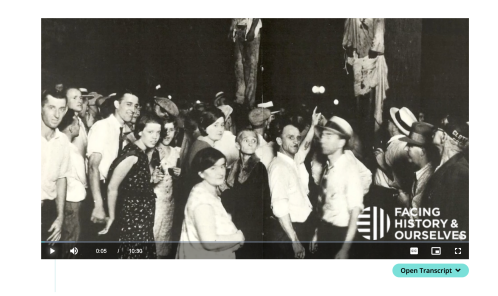

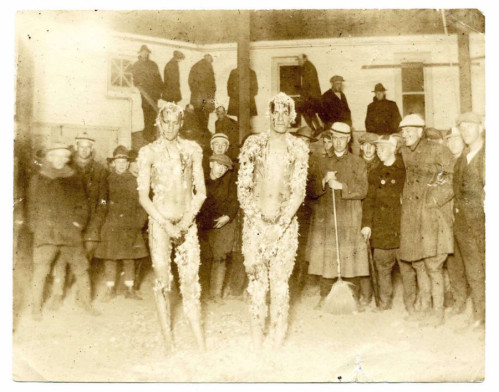

More than 4000 African Americans were lynched across 20 states in the Jim Crow era. This violence contributed to the political and economic marginalization of Black people, and upheld the social systems put in place earlier by slavery. Some members of lynch mobs created postcards, kept pieces of the rope used to hang their victims or took body parts from their victims as souvenirs or trophies to mark the gruesome acts of violence.

On slide number 4, review the lynching of Lige Daniels and the souvenir postcard shared afterward.

These types of postcards were created as mementos of the event by the onlookers. As you examine this postcard, review both the image and message from the sender.

Use text boxes on your slide copy to answer each question:

- Do the participants appear to be willing to be photographed with a dead body?

- Would you send this type of souvenir to a relative?

- What are your thoughts on the ages of the spectators present in the image?

- What questions or reflections do you have about the images?

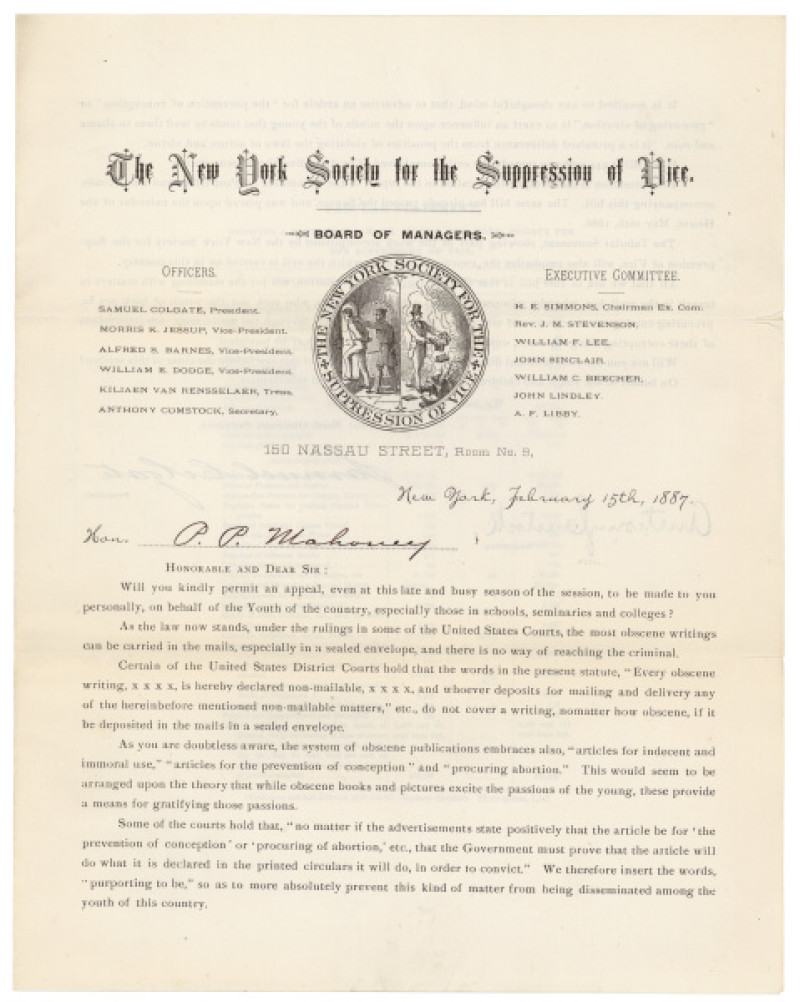

The act of sending “violent or obscene images by mail” was outlawed in 1873, as part of the Comstock Act. The ban was extended in 1908 to include sending material "tending to incite arson, murder, or assassination.

While some interpreted this law to include lynching postcards, enforcement was inconsistent and few were ever prosecuted. The lynching of Lige Daniels took place on August 3, 1920.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

How did the perpetrators of mob violence and lynchings use trophies and the media to normalize lynchings in the Jim Crow era?

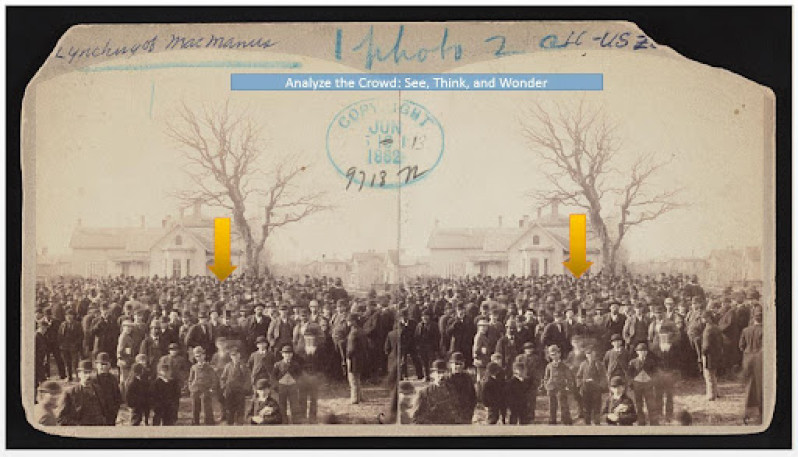

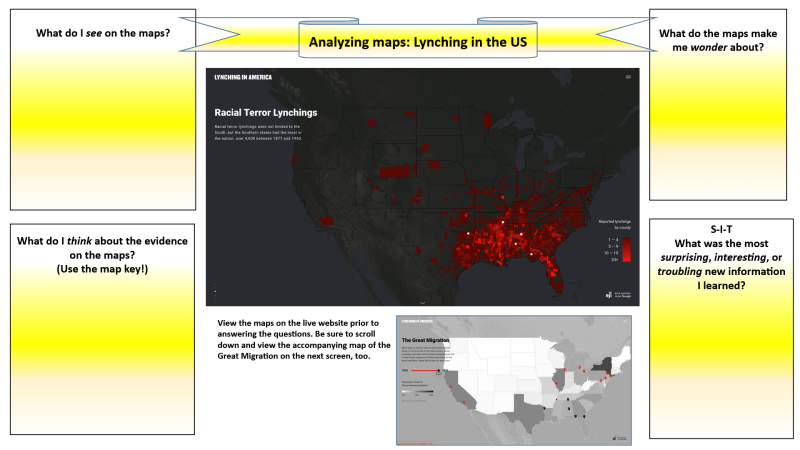

Lynching incidents were documented in local newspapers throughout the South, often with sensationalized headlines. Examine this image and pay careful attention to the crowds, clothes, children's ages, and reactions.

On slide number 5, analyze the crowd attending this lynching. (Note, we have used graphics to obscure the image of the victim.) Your teacher may ask you to describe what you See, Think, Wonder about the image. Turn and talk to a partner, or if working remotely, your teacher may allow you to use a collaborative document or slides, or meet via video conferencing. Analyze the image using these questions:

- How are the people in the image dressed?

- Do you see anyone expressing remorse?

- Do the assailants seem unafraid to commit murder in public?

Read this page from PBS’ American Experience on the history of lynching.

Share any additional thoughts with your partner.

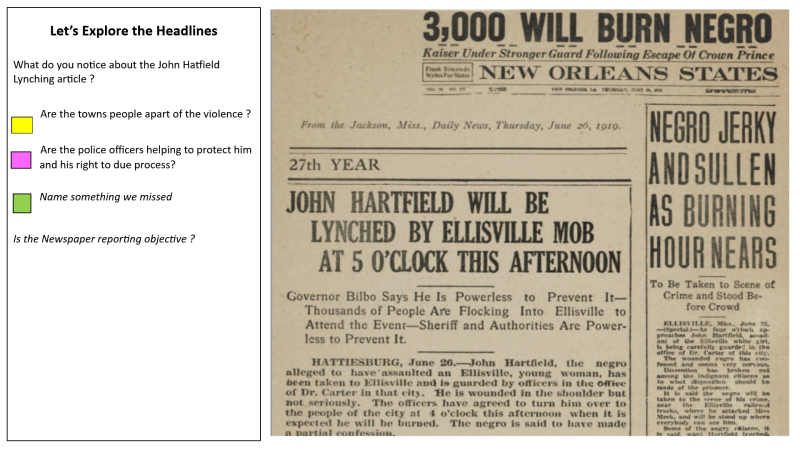

Examine this headline using the image on slide number 6. Use the text box on your slide copy to respond to each question.

Many of the victims of lynchings were originally accused of minor infractions or petty crimes. One of the most common infractions was looking at or associating with white women. Many victims were Black men who refused to back down from a fight.

Here are some other examples of headlines:

“Five White Men Take Negro into Woods; Kill Him: Had Been Charged with Associating with White Women" went over The Associated Press wires after a lynching in Shreveport, Louisiana.

“Negro Is Slain By Texas Posse: Victim's Heart Removed after His Capture by Armed Men" was published in The New York World-Telegram on December 8, 1933.

“Negro and White Scuffle; Negro Is Jailed, Lynched" was published in the Atlanta Constitution on July 6, 1933.

Newspapers shared the names and images of prominent white citizens who attended lynchings and often published pictures of smiling crowds next to the corpse. Countless numbers of men and women were killed without due process of law. The Comstock Act was not consistently enforced in most cases and was largely ignored by law enforcement and vigilante citizens.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on the slide as an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

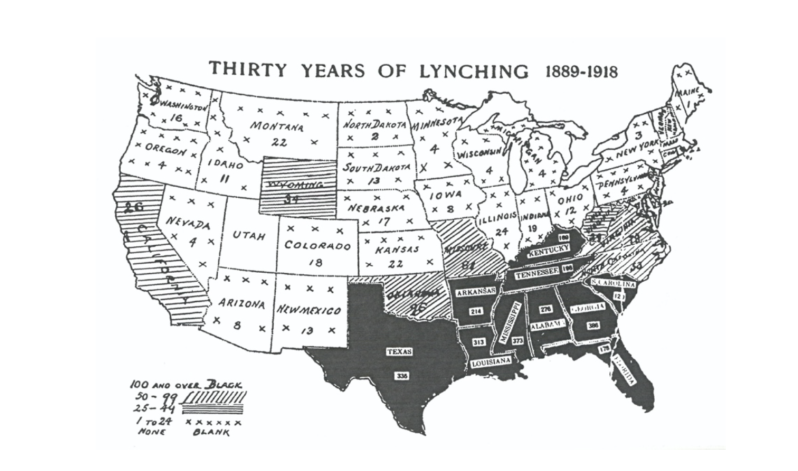

Where in the United States was lynching most commonly used as a form of racial terror?

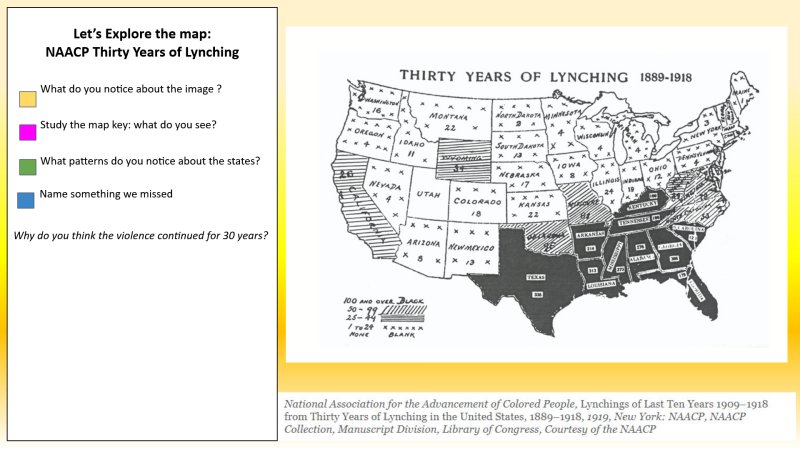

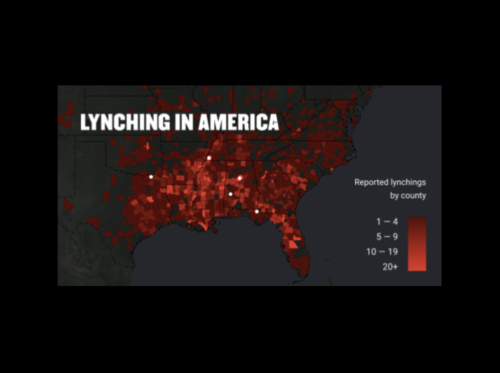

The largest numbers of lynchings were found in the southern states, but lynchings occurred all over the country.

Maps have been used throughout history to help visualize data and show patterns. The formerly enslaved activist and reporter Ida B. Wells used maps to expose racial inequalities and document acts of racial terror. Read more about how Wells and the NAACP used cartography in this entry from the Library of Congress.

Use the 1918 NAACP map on slide number 7 to answer the questions using the text boxes to respond.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has studied the history of lynching in America, creating this report. Explore the EJI interactive Lynching in America map. Use your cursor to hover over each state and manipulate the map to see when and where over 4,000 incidents of lynchings were documented. Pay close attention to those areas with a heavy number of incidents.

Use slide number 8 to compare and contrast the earlier NAACP map you viewed on slide number 7 to the two EJI maps. Be sure to scroll down on the EjI lynching map to view the Great Migration map included in the digital exhibit. Complete each question using the text boxes.

- Where do you see a pattern of multiple incidents of racial terror?

- Did the United States have any states without a reported incident of lynching?

- How does this map compare to the earlier NAACP map you viewed?

- According to the maps where are the greatest number of reported/verified lynchings in the US?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers as an exit ticket.

Extend:

How do we honor those who served their country, then lost their lives to acts of racial terror and violence?

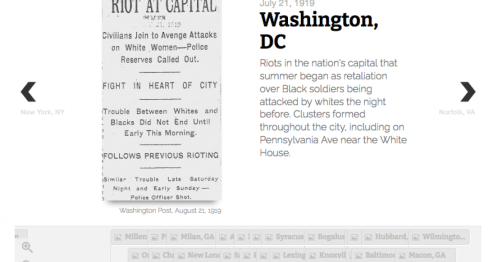

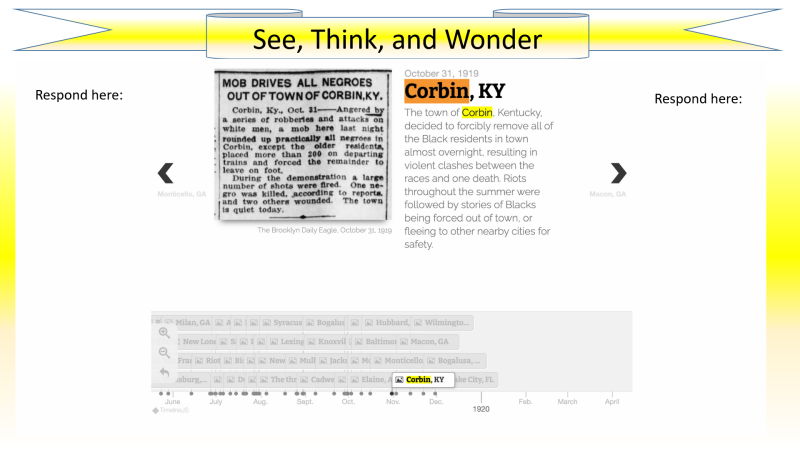

The summer of 1919, remembered as Red Summer should have been a nationwide celebration of soldiers returning home from World War I. Instead, it became violent as a series of mob-led attacks on black communities took place in dozens of cities across the country. Many were directed at the 380,000 Black servicemen returning home and seen as a threat to the social order, as they were less willing to be subordinate to Jim Crow policies. Some of the perpetrators included white soldiers returning from the war.

Read this Bunk excerpt, and explore the visual timeline preserving the history of this dark period in American history. Select 3-5 dates on the timeline to explore. Read the newspaper articles associated with each date.

- Do you see any patterns in the stories you read from the timeline?

- Did any of the stories you read involve veterans as victims or participants?

- What consequences, if any, did those committing the acts of violence face?

View this entry on the timeline from October 31, 1919, in Corbin, Kentucky. (Image is best viewed on the live website.)

This segment from the BackStory archive discusses the Corbin incident. Listen to the segment, then respond to the episode using text boxes on your copy of slide 9.

Racially motivated acts of terror did not end in 1919. The lynchings and acts of terror continued into the next three decades and were not exclusively targeted at Black victims.

View this entry on the BackStory blog to learn more about how Sundown Towns and the use of local ordinances, racial covenants, and unfair lending policies continued to segregate, discriminate and create barriers for BIPOC people for many more decades.

Share your final reflections about what you learned, using text boxes on slide number 10.

Today, organizations like the EJI have developed virtual and built environments to memorialize the faces and names of victims of lynchings and racial violence. Communities like Corbin, Kentucky have reclaimed their towns, rededicated their commitment to teaching the truth about their local history, and worked to create safe and welcoming neighborhoods for all residents and visitors.

On March 29, 2022, President Joseph R. Biden signed into law the first federal anti-lynching law in the history of the United States, over 100 years after Tulsa, and Red Summer. The bill is named for lynching victim Emmett Till, a 14-year-old lynching victim killed in 1955. This bill makes lynching a federal hate crime. Take a few minutes to read the President’s remarks from the solemn bill-signing ceremony.

- What are your thoughts about these efforts to teach about the history of lynching in America?

- Why did it take so long to pass a federal anti-lynching law?

- How would you honor the memory of those who have been victims of racial terror?

We are interested in your thoughts about this, as well as your feedback about these learning resources. If your teacher or a trusted grownup allows, email us your reflections or help your teacher complete this feedback form.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

“A Racial Cleansing in America from ‘Scene on Radio’ - Backstory Archive.” BlackStory - Backstory Archive. New American History BackStory Archive, January 1, 1970. https://backstory.newamericanhistory.org/episodes/blackstory/2.

Davis, Theodore R., Artist. Murder of a Negro at Mrs. Carter's house. New Jersey Pattenburg, 1872. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001695526/.

Farr, H. R, photographer. Lynching of MacManus. Minnesota Minneapolis, 1882. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2012646358/

“Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.” Accessed July 18, 2021, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/

“Maryland State Archives.” Legacy of Slavery in Maryland - Judge Lynch's Court Overview. Accessed July 21, 2021. http://slavery.msa.maryland.gov/html/casestudies/lynch_overview.html.

Mintz, S., & McNeil, S. (2018). Lynch Law in America. Digital History. Retrieved July 21, 2021, from https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=1113.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. “For the Good of America, Poster for the NAACP Anti-Lynching Campaign.” Poster for the NAACP anti-lynching campaign. 1922 Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 1922. https://nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2011.57.9.

PBS “Reconstruction America after the Civil War.” Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed July 18, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/weta/reconstruction/timeline/

“The Evidence of Things Unsaid.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, March 31, 2022. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/collection/evidence-things-unsaid.

“The Origins of Lynching Culture in the United States - YouTube.” Facing History/YouTube. Facing History.org, April 7, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hPdh46k7b38.

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc