This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

All History is Local: No Playbook

View Student Version

Standards

C3 Framework:D2.His.3.6-8.D2.His.3.9-12.

National Council for Social Studies:Theme 2 - TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGETheme 5 - INDIVIDUALS, GROUPS, AND INSTITUTIONS

National Geography Standards: Standard 6: How culture and experience influence people’s perceptions of places and regions

College Board AP U.S. History (Fall 2020)HISTORICAL THINKING SKILLS COVERED: SKILL 4.A – Identify and describe a historical context for a specific historical process or development.SKILL 5.A: Identify patterns or connections between historical developments.

TOPIC 8.6: Early Steps in the Civil Rights Movement (1940s and 1950s) – The three branches of the federal government used measures including desegregation of the armed services and Brown v. Board of Education (1954) to promote greater racial equality.

EAD FrameworkTHEME 1: Civic ParticipationTHEME 7: A People with Contemporary Debates and Possibilities

Teacher Tip: Think about what students should be able to KNOW, UNDERSTAND and DO at the conclusion of this learning experience. A brief exit pass or other formative assessment may be used to assess student understandings. Setting specific learning targets for the appropriate grade level and content area will increase student success.

Suggested Grade Levels: High School (9-12), U.S. History, Advanced Placement U.S. History, U.S. Government, Advanced Placement U.S. Government courses

Suggested Timeframe: 2 or 3 90-minute class periodsSuggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet or mobile device

Key Vocabulary

Almond Jr., J. Lindsay - Democratic governor of Virginia from 1958 to 1962, supported Massive Resistance as a member of the political group known as the Byrd Organization

Bridges, Ruby - civil rights activist and first Black student to attend the previously all-whites William Frantz Elementary School in 1960 in Louisiana

Brown v. Board of Education - a 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case that ended legal segregation in U.S. schools by ruling that "separate but equal" public facilities were unconstitutional

Burley High School - Charlottesville-based school that existed from 1951 to 1967 to serve Black students from Charlottesville, Albemarle County, Greene County, and Nelson County

Byrd Organization - political faction in Virginia led by Harry F. Byrd, a Democratic state senator, governor, and U.S. senator; the group believed in fiscal conservatism and opposed the Brown v. Board ruling

Desegregation - the process of ending the separation of racial groups in the U.S.

Integration - the social process of creating an environment where all racial groups can coexist and participate fully

Lane High School - a public school in Charlottesville, Virginia, opened in 1940; from 1940 to 1959, the student body was all white; it closed in 1958 by order of the governor, and reopened in 1959 as a desegregated school; it permanently closed in 1974

Lugo, Alicia - educator and community leader from Charlottesville who attended and taught at the all-Black Burley High School; served for 11 years on the Charlottesville City School Board

Massive Resistance - a political effort in the late 1950s, especially in the South, to create laws and policies to prevent the desegregation of schools

Oral History - a field of study and a method of gathering, preserving, and interpreting the voices and memories of people, communities, and participants in past events.

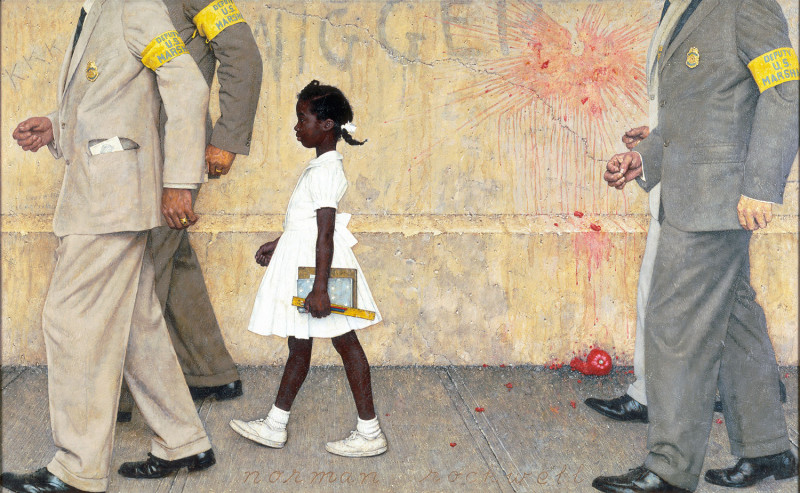

Rockwell, Norman - an American artist who painted scenes of mid-century American life in the 1930s-1940s and beyond, who is best known for illustrating 321 covers for The Saturday Evening Post; later in his career, he shifted focus to pictures depicting civil rights and America’s war on poverty

Writ large - on a large scale, clear, or obvious

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tips

New American History Learning Resources may be adapted to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in pairs or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs or Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge.

These Learning Resources use Harvard University’s Project Zero thinking routines. The specific routines used are: the “See-Think-Me-We” thinking routine.

This Learning Resource also uses materials from Bunk History. Bunk History primarily hosts excerpts, videos, audio content, curated collections and exhibits, and a mapping feature, all designed to connect the present to multiple people, places, and events in American History. A Bunk History “Collection” is featured in this Learning Resource. Teachers may also create their own Collections. Instructions on creating Collections can be found here.

These Learning Resources follow a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

For Students:

Public education in America has had a complicated history. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in its Brown vs. Board of Education case that the idea of racially segregated public schools was unconstitutional. After the decision, states, locales, and leaders responded in different ways. In Charlottesville, Virginia, the governor closed its schools in 1958 – in defiance of the Supreme Court decision – rather than offer a desegregated school. While the courts eventually overruled the governor and forced desegregation, this period of tension greatly impacted the Charlottesville community. This Learning Resource tells that story, and the legacy it has left.

Engage:

How did Americans react to school desegregation?

After the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, communities across America – and even within the same town or city – responded differently. Some were quick to desegregate their schools; others actively resisted change.

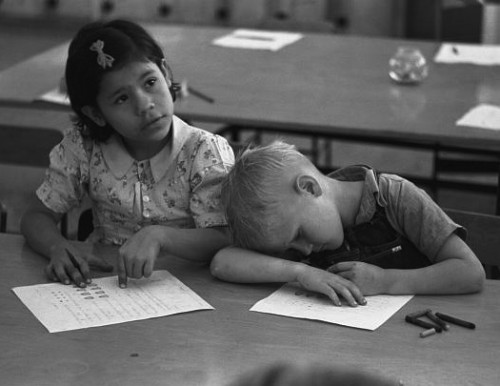

In November 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges was the first Black student to attend William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans after a federal court ordered the school to desegregate. Artist Norman Rockwell painted his version of the event in 1963 in the work “The Problem We All Live With.”

VISUAL DISCOVERY – Examine this painting independently. Organize your thoughts using the “See-Think-Me-We” thinking routine:

1) See = Look closely at the work. What do you notice? List your observations.

2) Think = What’s going on in the work? What might it mean? What makes you say that?

3) Me = What connections can you make between you and the work?

4) We = How might the work be connected to bigger stories: about the U.S. and our place in it?

After you answer the questions independently, share your responses as a group of three or four. Nominate a record keeper, and record your answers in this graphic organizer. Then nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class. Your teacher may allow you to make a digital copy or use a paper copy provided by your teacher.

After the discussion, read the story behind the artist and the event he captured in this article. After you read, answer these independently first:

- Based on the article, what are important elements of Rockwell’s painting?

- Explain how Ruby Bridges’ family made the decision to enroll Ruby at William Franz Elementary School and how the decision impacted Ruby and the family.

- How did “The Problem We All Live With” mark a change for Rockwell as an artist?

- How does Ruby Bridges’ story fit into the larger American story of freedom & equality?

Share your responses in the same group of three or four. Nominate a different group reporter and discuss as a class.

ZOOMING OUT – “The Problem We All Live With” represents a specific example of how one community in New Orleans in 1960 responded to the U.S. Supreme Court’s order to desegregate schools. How did Virginia, as a state, respond?

In pairs, read through the Encyclopedia Virginia article about Massive Resistance.

As you read, have each pair record their answers to these questions:

- Define Massive Resistance in one sentence.

- Origins – What caused Massive Resistance in Virginia?

- How did the Byrd Organization grow support for Massive Resistance?

- How did the courts undo Massive Resistance?

- What is the legacy of Massive Resistance in Virginia?

Then nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

What was it like for students at schools in Virginia that were desegregating?

One of the locales that became a part of the Byrd Organization’s Massive Resistance plan was Charlottesville. Before the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, Charlottesville had two main high schools: Lane High, where White students attended (opened in 1940), and Burley High, which served Black students from Charlottesville and neighboring Albemarle County (opened in 1951). In September 1958, in response to the Brown decision, Virginia Governor J. Lindsay Almond Jr. closed Lane to prevent desegregation. The courts reversed Almond’s order in January 1959 and, in September of that year, Black students began attending Lane. Some, however, chose to stay at Burley, which closed in 1967.

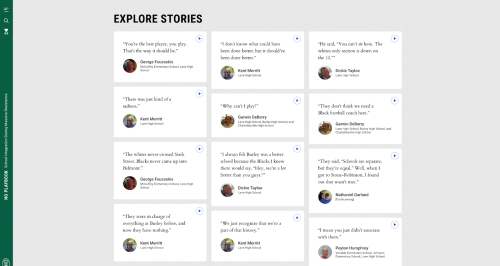

The Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society’s “No Playbook” oral history project archive holds interviews with dozens of Burley and Lane students who lived through this dynamic period of social change.

Read the introduction to the oral history project independently and answer the following questions.

- Why did the managers of the project start with a focus on sports, and what did they learn as they worked?

- Why do you think this project is called No Playbook?

- The text on the site states: “These individual stories help us to understand the ways that full integration has yet to be achieved.” In your view, what does “full integration” within a school community look like, and to what extent do you think it has been realized at your school?

Discuss your answers as a class.

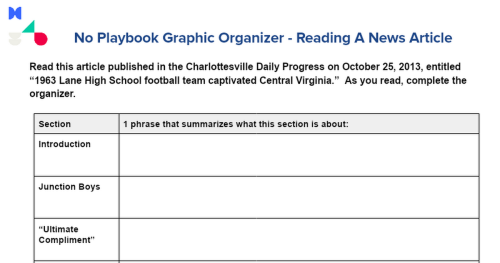

Next you will find and get to know three different students who attended Burley or Lane. First, explore their stories independently by going to the Explore Stories section of the website.

Complete a personal profile for each of the three students using this graphic organizer. Click on each student’s name for their biography and click “more clips” to view more excerpts from their interview, as well as the link to their full interview.

After completing your independent research, share your most interesting or powerful profile with a partner. Lastly, share these ideas in a whole class discussion.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

How did football help unite Lane High School after it integrated?

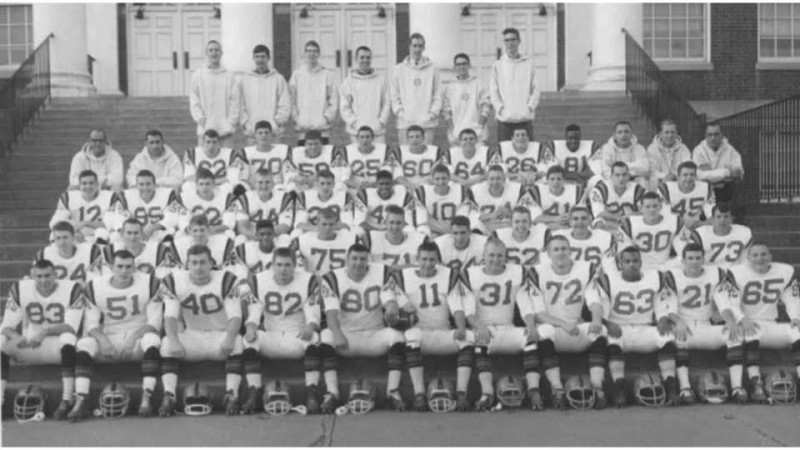

Many know the story of the Titans high school football team of Alexandria, Virginia in 1971, thanks to a Disney movie released in 2000 starring Denzel Washington. However, before the Titans’ inspiring efforts to integrate their team, Lane High in Charlottesville boasted a successful program during its early years of integration. Lane notched a 53-game winning streak from 1962 to 1967, according to Charlottesville’s newspaper, The Daily Progress.

First, read the quote from Julia Shields, who started her teaching career at Lane High School in 1967:

“I do think athletics helped not only the members of the team, but those of us who would go to games and cheer for kids, regardless of skin color or background. That was a help, for sure.”

Answer these questions with a partner:

- What does this quote say about the value of the Lane High football team to the school?

- To what extent do you think sports bring a diverse community together?

After your partner chat, nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

Then, on your own, read this article published in The Daily Progress on October 25, 2013, entitled “1963 Lane High School football team captivated Central Virginia.” (Shared via the No Playbook archives).

As you read, complete this graphic organizer.

After you read, pair up with the same partner and answer:

- How did football help unite Lane High?

- What limitations do sports have in uniting a community?

After your partner chat, nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

How did desegregation in Charlottesville schools compare to schools in other locales?

First, listen to this segment from the BackStory podcast archives, an interview conducted by historian Ed Ayers in 2010 with Alicia Lugo. Lugo graduated in 1958 from the all-Black Burley High in Charlottesville. After earning a teaching degree from Hampton University, she returned to Burley in 1965 to teach. Burley closed two years later, and she then taught at an integrated school in Charlottesville, called Walker, one of two junior high schools in the city.

“Projectors and supplies don’t make the excellent educational experience. You have to make the child want to learn, and that’s what we came up under [at Burley].”

As you listen, answer these questions independently. You will need to start/stop the audio as prompted in the questions below::

1. THE INTERVIEW – question covering the first 8 minutes: According to Ms. Lugo, what misconceptions did people have about Burley High?

2. THE INTERVIEW – question covering the first 8 minutes: According to Ms. Lugo, what are the limitations to a truly integrated school system?

3. THE INTERVIEW – question covering the first 8 minutes: Why did Ms. Lugo leave teaching?

4. THE COMMENTARY– question covering minutes 8 to 12: According to the historians, what is the tension at the heart of Ms. Lugo’s story?

In partners, review the answers to each question. Then, nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

Alicia Lugo passed away in 2011. In 2014, the students of Charlottesville City Schools voted to name a new school, Lugo McGinness Academy, after Alicia Lugo and Rebecca McGinness, both long-time city school educators.

To end the discussion, answer:

What questions would you ask Ms. Lugo if she were in front of us today?

ZOOMING OUT – In Charlottesville, school desegregation was complicated by Massive Resistance and the closing of the all-Black Burley High. How did school desegregation play out in other communities in the U.S.?

This Bunk Collection zooms out to include three related stories: how a generation of Black girls was fighting to desegregate schools long before 1954’s Brown v. Board decision, how the North also struggled to desegregate schools, and how Southern segregation academies were created for white students and their families who didn’t want to attend a desegregated school.

For each article in the Bunk Collection, answer these questions:

- Summarize the story in one sentence. (Who/what > did what? > when? > where? > why/how?)

- What are two ideas or people that support the main story?

- What are two questions you still have about how the story played out?

Review the answers to each question with a partner, then nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class. To close the whole class discussion, answer:

How were the stories of Charlottesville and these other locales similar? How were they different?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

How can full integration be achieved in U.S. schools?

The legal concept of desegregation is different from the social idea of integration. In some ways, schools – and communities in the U.S. writ large – are still working toward full integration in the truest sense.

In groups of three or four, begin by making a list of differences between desegregation and integration by conducting web research. Nominate a group member to record ideas.

When groups are ready, nominate a different group member to share ideas during a whole class discussion.

Next, read the two quotes below:

QUOTE #1:

“While Brown v. Board attempted to get rid of segregation in American schools, because of policy decisions around education, housing, and zoning, the sad truth is that schools today are as segregated as they were in the late 1960s.”

QUOTE #2:

Ed Ayers, historian: “So why do you think that integration did not turn out the way that people dreamed of?”

Alicia Lugo, Charlottesville educator: “Because I think that there were those people who had no intention of letting it turn out that way. The only way systems change is that you treat them like a rubber band. As long as you keep the tension on the rubber band, you can change its shape. But once you let go of that tension, once you let go of that scrutiny, it drops right back into its original form…the scrutiny was gone because who can complain? Now we have the desegregated schools, so you got what you asked for.”

Compare the two quotes by answering these questions:

- What makes the ideas in these quotes similar to each other?

- What makes them different from each other?

Review the answers to each question with a partner, then nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class.

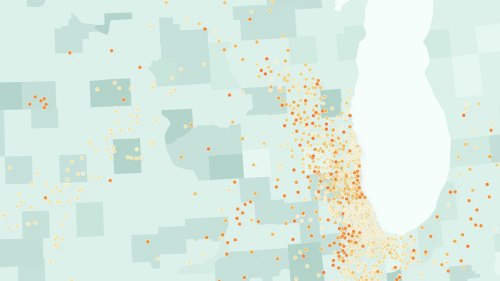

Next, read through this article on school integration from The Conversation, and analyze the map from The Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University.

Then answer these questions:

- What are the main reasons why schools are not racially integrated today?

- What specific examples and data support the idea that school integration works?

Review the answers to each question with a partner, then nominate a group reporter and discuss as a class. To close out the whole class discussion, answer:

What changes can be made to schools to make them fully integrated in the truest sense?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. “About This Project.” No Playbook — School Integration During Massive Resistance. Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://noplaybook.albemarlehistory.org/about.

BackStory. “Hometown Hero.” Segment in School Days: A History of Public Education. BackStory, produced by Virginia Humanities. Aired September 7, 2012. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://backstoryradio.org/shows/school-days-a-history-of-public-education-2/#segment-hometown-hero

CrashCourse. “School Segregation and Brown v Board: Crash Course Black American History #33.” YouTube video, 12:29. February 11, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBlqcAEv4nk.

Harvard Graduate School of Education. 2022. “PZ’s Thinking Routines Toolbox | Project Zero.” Pz.harvard.edu. Harvard Graduate School of Education. 2022. https://pz.harvard.edu/thinking-routines.

Hershman, James H., contributor. “Massive Resistance.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, 2025. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/massive-resistance/.

Kennedy Center. “Norman Rockwell + The Problem We All Live With.” Kennedy Center, last updated March 2025. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://www.kennedy‑center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media-and-interactives/media/visual-arts/norman-rockwell--the-problem-we-all-live‑with/.

Lugo‑McGinness Academy. “Program History.” Lugo‑McGinness Academy, Charlottesville City Schools. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://lugo‑mcginness.charlottesvilleschools.org/21001_2.

Metzinger, Fritz. “1963 Lane High School Football Team Captivated Central Virginia.” The Charlottesville Daily Progress, October 25, 2013. https://dailyprogress.com/sports/high-school/article_eb040a52-3d00-11e3-b4c9-0019bb30f31a.html.

Noguera, Pedro A. “U.S. Schools Are Not Racially Integrated, Despite Decades of Effort.” The Conversation, May 13, 2022. Republished from The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/us-schools-are-not-racially-integrated-despite-decades-of‑effort‑177849.

“School Desegregation, in Depth.” Bunk History. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://www.bunkhistory.org/collections/x6cd1a.

“The Segregation Explorer.” The Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, 2019. https://edopportunity.org/segregation/explorer.

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc