This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Seizing Freedom: A Tulsa Postcard

View Student Version

Standards

Common Core:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideasC3 Framework:

D2.Civ5.9-12. Evaluate citizens’ and institutions’ effectiveness in addressing social and political problems at the local, state, tribal, national, and/or international level.D2.Civ.12.9-12. Analyze how people use and challenge local, state, national, and international laws to address a variety of public issues. D2.Civ.13.9-12. Evaluate public policies in terms of intended and unintended outcomes and related consequences.National Council for Social Studies:

Theme: Power, Authority, and GovernanceTheme: Civic Ideals and PracticeNational Geography Standards:

Standard 17: How to apply geography to interpret the past

Teacher Tip: Think about what students should be able to KNOW, UNDERSTAND and DO after this learning experience. A brief exit pass or other formative assessment may be used to assess student understandings. Setting specific learning targets for the appropriate grade level and content area will increase student success.

Suggested Grade Levels: Middle School 6-8 / High School (9-12)

Suggested Time Frame: 2-3 block classes (90-minute) or 4-5 class sessions, 45-minute each

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet, or mobile device

Key Vocabulary

14th Amendment - A constitutional amendment added after the U.S. Civil War that provided citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the United States

Antebellum - the time period before the Civil War

Assailant - a person who attacks someone violently

Caste system - a class structure that is determined by birth. Loosely, it means that in some societies, the opportunities you have access to depend on the family you happened to be born into.

Chattel Slavery - the enslaving and owning of human beings and their offspring as property, able to be bought, sold, and forced to work without wages

Contested Landscape - competing symbolic value of a given cultural and/or physical space or region as seen by various religious, ethnic, or racial groups. It might include monuments, public spaces, and other representations of political power.

Debt Bondage (also referred to as Debt Servitude, or Peonage) - the financial enslavement of a person in exchange for living expenses.

Disenfranchise - to take away someone’s right to vote

Discrimination - unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people or things, especially on the grounds of race, age, religion, gender, or sexual orientation.

Endorsement - approval or public support

Enslave - to force someone to be a slave

Freedman / free person - a person who has been set free from being enslaved

Hysteria - a situation in which individuals or groups of people behave or react in an extreme or uncontrolled way because of fear, anger, or other emotions.

Iconography - the use of images, symbols or objects to represent a feeling, emotion, or belief

Inferiority - having little or no value, power, or influence

Jim Crow - racial segregation and discrimination enforced by laws, customs, and practices, especially in the southern U.S. from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 until the mid-1900s

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) - a white supremacist group founded in 1865 to intimidate African Americans and other minority groups from asserting themselves in any way, including politically

Legacy - money, property, or ideas that are handed down, from one generation to the next

Lynching - the illegal killing of people by gangs of violent vigilantes

Memorabilia - historical objectives found or kept that link people, places, or things to an event or special occasion

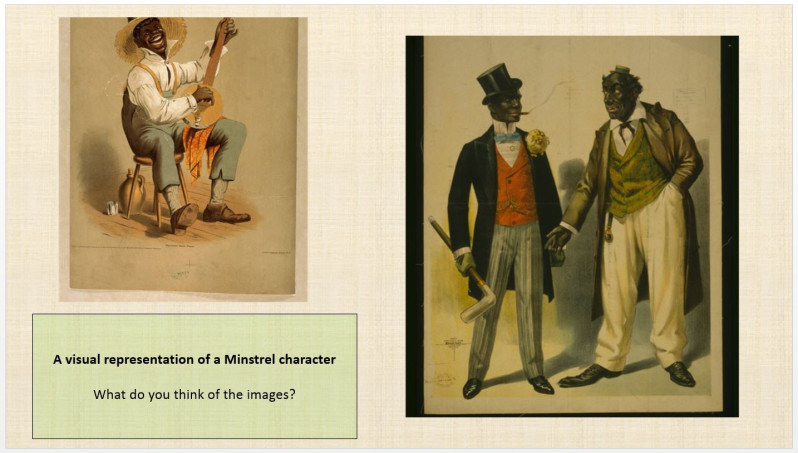

Minstrel Show - a form of performance created around the 1830s where white people dress up and deliver caricatured performances of African American culture (see the Smithsonian NMAAHC Minstrel Shows)

Monument - a statue or building created to retain the memory of a person or event

Norms - behaviors and customs that are widespread and usual

Perpetrator - a person who commits an illegal, criminal or evil act

Plessy v. Ferguson - A landmark Supreme Court case that upheld the legal separation of facilities for different races, establishing the “separate but equal” policy for many years

Populist - political stance emphasizing the “Idea of the People”

Primary Source - Document or material culture, (artifacts, diaries, newspaper articles, pictures, clothing, recordings, maps, etc.) from a specific point in history

Racial Etiquette - a code of understood rituals, social interactions, or behaviors that governed the actions of people of color in the presence of white people.

Racism - when a group of people is treated unfairly because of their race/skin color

Racial terror - the threat or act of violence based on race used to intimidate and cause fear in its victims

Racist - an ideology predicated on the notion that certain races are inferior to others

Remorse - a feeling of regret

Restrictive Covenant - contractual agreements that prohibit the purchase, lease, or occupation of a piece of property by a particular group of people, usually African Americans, immigrants, or Jewish people

Satirize- the use of humor to tease or make fun of a person’s weaknesses or flaws, to criticize or expose foolish, wrong, or corrupt behaviors or ideas

Segregation - race-based separation in public spaces including schools, public transportation, restroom facilities, and neighborhoods; many communities in the United States were segregated for centuries, and while the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s removed many legal barriers, some are still socially segregated.

Souvenir - a keepsake/memento purchased or found to remind someone of a special event, place, or time

Status quo - a Latin term meaning the way things presently are, unchanging

Stereotype - a mistaken idea or belief many people have about a thing or group that is based upon how they look on the outside, which may be untrue or only partly true. Stereotyping people is a form of prejudice and might be used to discriminate against another person, embarrass or humiliate them.

Subservient - in service to someone of a higher social rank

Vigilante - A person or group who enforces the law or inflicts punishment without the legal authority to do so

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tips:

This Learning Resource includes language in the body of the text to help adapt to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning. If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in partners or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs or Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge.

This Learning Resource includes audio segments from the VPM podcast, Seizing Freedom, and include content about suppressive laws known as Jim Crow laws, acts of racial terror including lynching, and other discriminatory acts or customs used daily in the post-Reconstruction era to remove the rights and freedoms of African Americans and other minority groups in each locale, or by state legislatures. The Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling legalized a caste system on a federal level. African Americans were exposed to this system of racial indignity at every turn. Although freed legally, Native Americans, Asians, nonwhite immigrants, and formerly enslaved people were forced back to a subservient social status by white Americans in positions of power following Reconstruction. They used these Jim Crow laws and the unspoken “racial etiquette” backed with violence to control minorities in America. Additional segments of the podcast may be used for teacher background knowledge or assigned to students for independent exploration, but educators should preview the episode in its entirety first. For more examples of the Tulsa Race Massacre “souvenir” postcards or other images of Greenwood, visit the Tulsa Historical Society Museum Postcard Images. Note: Some images may be too graphic for younger students, always preview all images and resources prior to classroom use.

This era of American history will be challenging yet informative for most students to read, hear and reflect upon. As an educator, you must be mindful of the students’ emotional well-being as they continue on their educational journey learning about sensitive topics in our nation’s history. Members of the educational community should be partners and included in supporting our nation’s history, student learning, and teachers. They all should be invited to visit the virtual exhibit on the unspoken “racial etiquette” from the Jim Crow Museum and other digital scholarship linked within this Learning Resource. Let’s Talk from Learning for Justice contains student learning when appropriate. Ferris State University provides resources to help explain additional teaching tips for helping students understand racially charged content. This article shares additional information on areas identified as Black Wall Street during this era.

This Learning Resource uses a KWL strategy from Facing History, and the Question Formulation Technique, a multi-step group activity from the Right Question Institute that allows students to strengthen their skills in creating their own questions. It will be helpful to read the QFT Outline before conducting the Engage activity. In addition, this Learning Resource uses “Thinking Routines” from Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education that has developed learning strategies that encourage students to add complexity to their thought processes. For an overview of Project Zero’s methodology, you may want to read its Exploring Complexity Bundle. Specifically for this lesson, students will use these thinking routines: See, Think, Wonder; I Used to Think...Now I Think; Take Note; Values, Identities, Actions; Headlines.

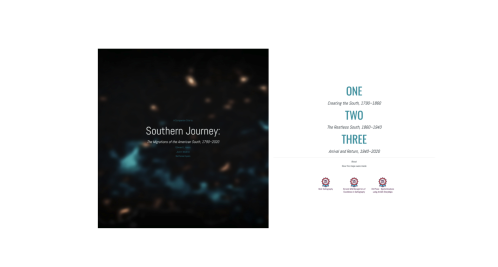

Bunk Collections, pre-selected Bunk excerpts that share a common topic or theme, are featured in this Learning Resource. The American Panorama StoryMap, Southern Journey: Migrations of the American South, 1790-2020, includes three separate parts of the map. Sections of the StoryMap are used to illustrate patterns of migration. A separate lesson in the New American History Learning Resources Library on The Trail of Tears may be useful to review before discussing the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

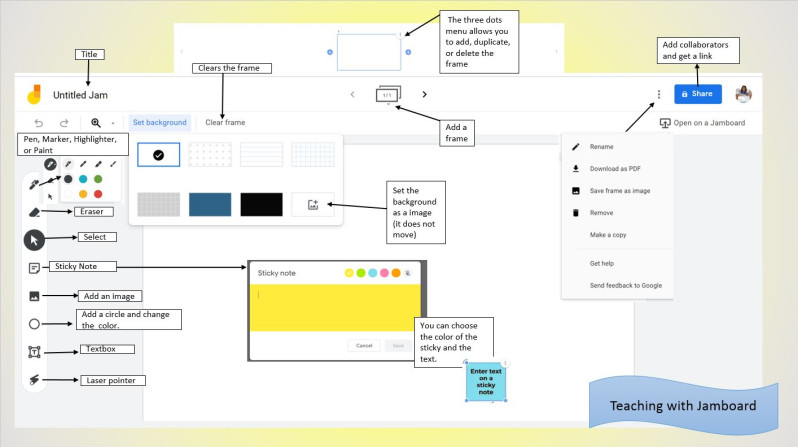

These learning resources provide a view-only copy of images to your students using a collaborative tool, a Google Jamboard. You will need to make a master copy of the Jamboard for your personal Google Drive. For instruction, make separate copies of your master copy to use with your students, and set permissions to “anyone may edit.” We also provide all content for the Jamboard as Google Slides for educators to make further modifications as needed. This slide explains the Jamboard functions. (See image of Jamboard 1 below.)

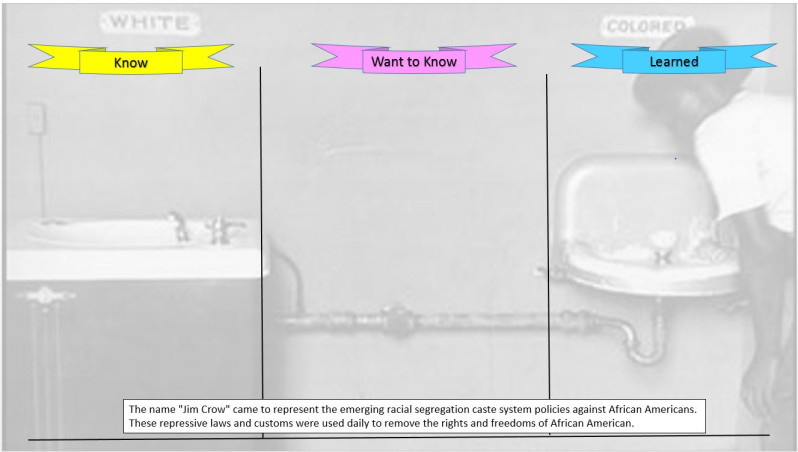

On Jamboard 2 students will complete a KWL chart, sharing What they Know about it, Want to know, and will Learn at the end of this lesson about Jim Crowism. Jamboard 3 includes a video from CBS Sunday Morning, and Jamboard 6 contains examples of the unspoken “racial etiquette” used by white Americans during this era. Student answers will be posted on a sticky note, and the color of each one should correspond with the color of each column. The EduProtocols Sketch and Tell strategy is also used.

Our Learning Resources follow a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience, or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

For Students:

Building empathy and understanding as a learner

This era of American history will be challenging yet informative for you as a student to read, hear and reflect upon as you continue on your educational journey, including learning about sensitive topics in our nation’s history. Your family and community members should be partners and included in supporting your learning about history, alongside your classmates and teachers.

These learning resources include audio segments from the VPM podcast, Seizing Freedom, and include content about suppressive laws known as Jim Crow laws, acts of racial terror including lynching, and other discriminatory acts or customs used daily in the post-Reconstruction era to remove the rights and freedoms of African Americans and other minority groups in local communities across the country, or by state policymakers. The Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling legalized "separate but equal" on a federal level. Although freed legally, African Americans, including freed Blacks and the formerly enslaved, Native Americans, Asians, and nonwhite immigrants, were forced back to a subservient social status by some white Americans in positions of power following Reconstruction. They used these Jim Crow Laws and the unspoken “racial etiquette” backed with violence to control minorities in America.

Engage:

What are Jim Crow laws?

In this lesson, you will learn about a period of American history where discriminatory practices were signed into law at the state and local levels in many parts of the country to purposely segregate and prevent Black Americans and other minority groups from fully exercising equal rights as citizens.

You will make a copy of a Jamboard or use Google Slides provided by your teacher. Jamboard 1 will explain how a Jamboard works, and you may practice using sticky notes to respond to questions and share your ideas.

On Jamboard number 2, look at the KWL chart. You will respond to the categories in the following columns, ”Know,” “Want to Know,” or “Learned” using stickies with the same colors pictured in each column.

View this video from CBS Sunday Morning about the history of Blackface and Minstrel Shows. When you are finished, take a few moments to reflect and continue to Jamboard 3. (Note: this video and other content contained in these learning resources include information that may be uncomfortable for you and your classmates to discuss, however, they are essential to our understanding of the history of race, slavery and civil rights in the United States.)

In the early 1830s, Thomas Dartmouth Rice created the antebellum character, Jim Crow. "Daddy Rice" was a white actor who performed minstrel shows, a song-and-dance act whose exaggerated antics were popular among his white audiences. In this act, he covered his face with black makeup and performed jokes and songs impersonating a stereotypical Black slave figure. Politically, these images were first used to satirize President Andrew Jackson's populist policies. The name "Jim Crow" came to represent the emerging racial segregation or caste system policies that targeted African Americans.

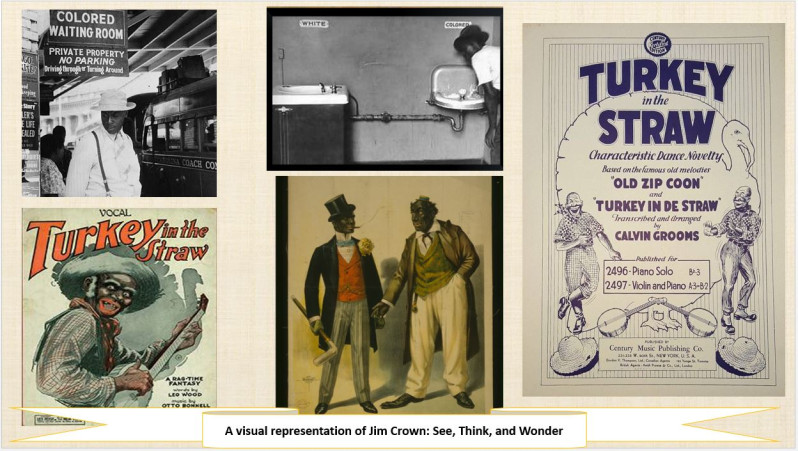

View these images on Jamboard 3 and reflect on the following questions:

- What do you think of the images of the Jim Crow character?

- How did the Jim Crow character stereotype Black people during this era?

Listen to this segment from “They Can’t Keep Me Out,” an episode of the Seizing Freedom podcast, featuring narratives from the people who experienced emancipation firsthand.

Activist Ida B. Wells wrote on the subject, accusing white Americans of reporting false accusations of assault or other criminal acts by Black people to the authorities, and inciting violence and acts of racial terror including lynching to intimidate people of color who were now seen as economically and politically competitive. Wells reported many white people were unable to accept that Black men and women were no longer chattel property.

After listening, reflect on what it means to have “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

- Did the obstacles described in the narrative stop the newly freed people from owning a business?

- Should anyone born in America have these rights?

- Are the formerly enslaved people asking for anything any other American would not want?

- So what does it mean to be free in America?

Racial stereotyping and segregation by servitude for many minorities continued after Emancipation and the Civil War ended, as free Blacks endured decades more of violence, including lynching.

These racial tensions escalated in the early to mid-20th century leading up to the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. You will explore this event in more detail in the next section of these learning resources.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers to the podcast questions as an exit ticket.

Explore:

How did thriving Black communities such as Greenwood become known as Black Wall Street?

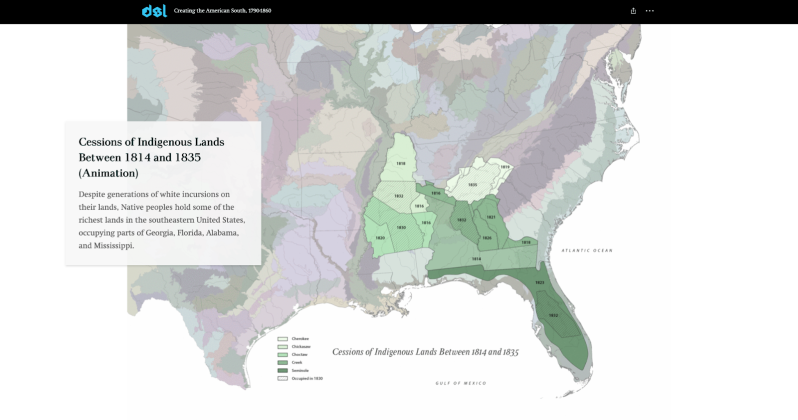

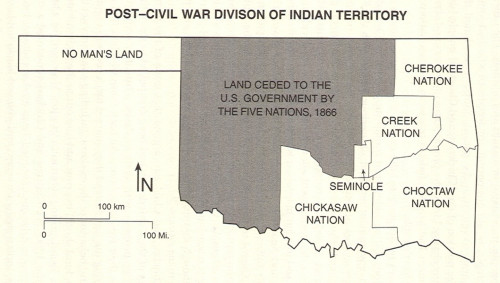

Before statehood, the Oklahoma territory became home to many displaced Native Americans as a result of the Trail of Tears. Take a few minutes to explore the StoryMap, Southern Journey: Migrations of the American South, 1790-2020.

View the animation in part One of the StoryMap to learn about the forced removal of Indigenous peoples. Some of these Native Americans were slave owners themselves, and both free and enslaved Black people came to the territory at this time.

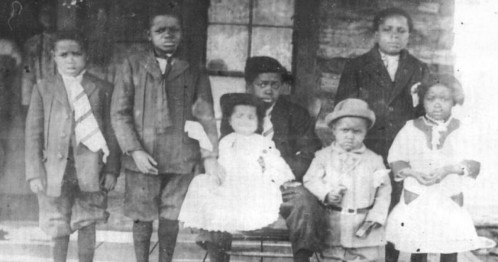

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, free Black people in the Tulsa area began to create towns, their own local governments, businesses, and post offices. Indigenous peoples lived and worked alongside Black people, some of whom both they and some white settlers had formerly enslaved. During this time, Black and indigenous people were not afforded all of the same rights as white citizens, yet some ideas of freedom and equality outlined in the U.S. Constitution seemed more attainable in this part of the country for minorities during the Jim Crow era than they did in the southern and eastern parts of the United States.

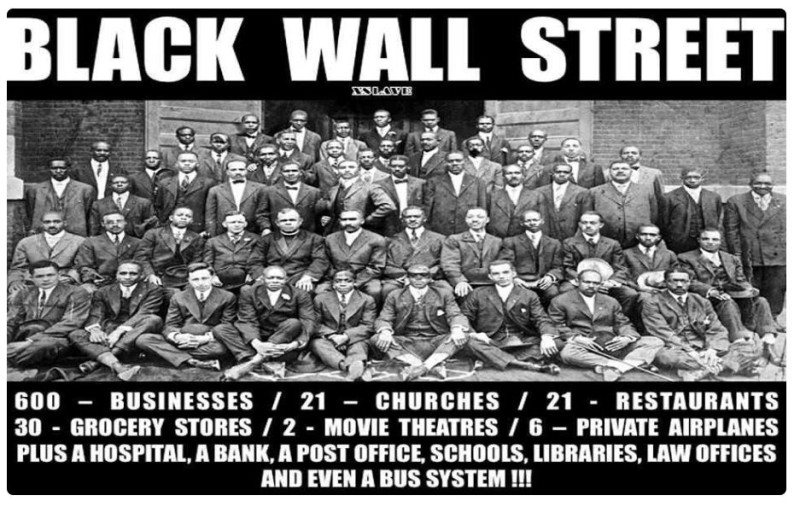

Tulsa's Greenwood District began in the early 1900s when Oklahoma was still a territory. In 1907, Oklahoma officially became a state. Greenwood became known as Black Wall Street and had over 600 Black-owned businesses operating in the early 20th century. (A few other cities also had neighborhoods referred to as Black Wall Street, as they also had many thriving Black-owned businesses.)

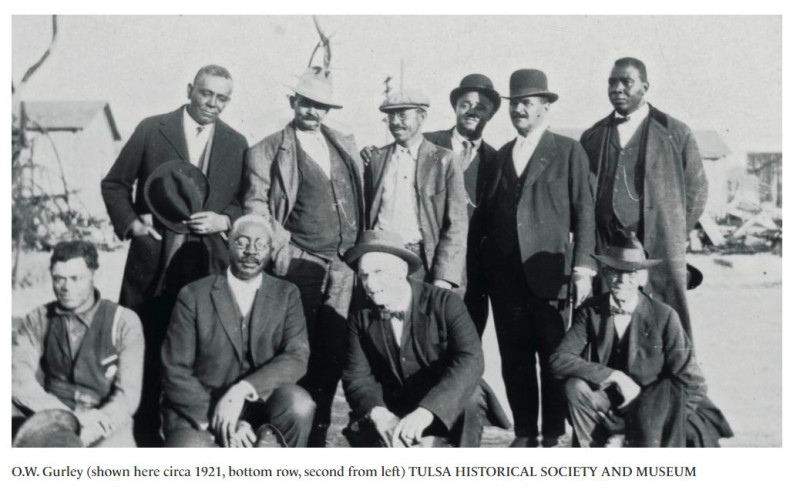

The Greenwood District included one of the largest hotels in the state, owned by O. W. Gurley. It is estimated Gurley owned at least 100 businesses in Greenwood himself. Black-owned businesses were important during that time, as Black people were not always welcome in white-owned shops and businesses, or service-related industries providing healthcare and beauty treatments, dining, and travel accommodations.

Use a sticky note to respond to the following questions using Jamboard 4.

- Analyze the clothes of those pictured in the image. Do the men pictured seem inferior to their white counterparts?

- Do these men appear to be dependent on whites for anything?

The Greenwood District functioned independently of its white counterparts. In the time of segregation, and Jim Crow, this was almost unheard of in many parts of the country. During this time, Oklahoma had more Black towns than any other place in the country.

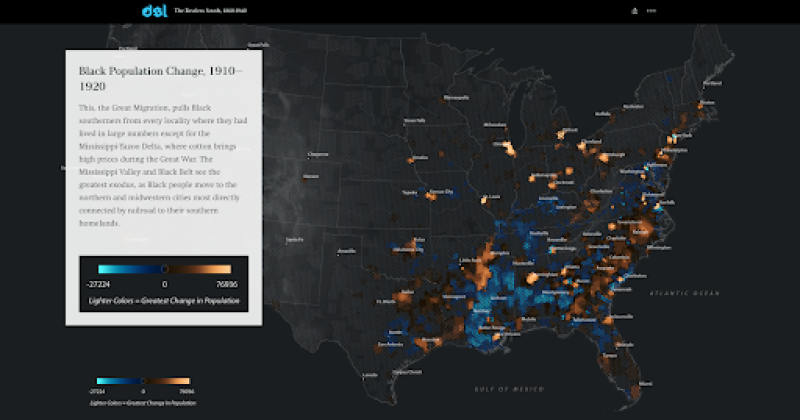

Take a few minutes to explore part Two of the StoryMap, Southern Journey: Migrations of the American South, 1790-2020. Explore population changes for Black and white Americans 1910-1920, and compare these to later decades. (View all maps in the StoryMap platform, images below are a guide to help you navigate the StoryMap.)

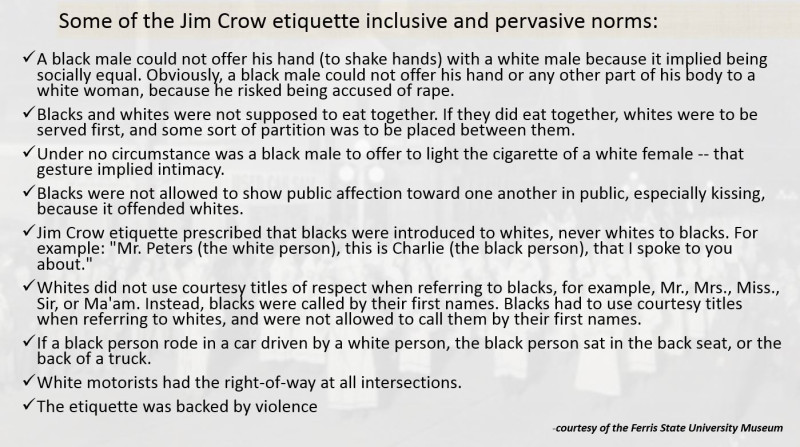

As the state’s population grew, so did the racial tensions. Minorities from around the country flocked to Tulsa, the “Black Wall Street.” An unspoken “racial etiquette” emerged during Reconstruction, continuing to segregate and maintain the Jim Crow power structures of the era. Take a few minutes to explore these digital resources from Tulsa and the Jim Crow Museum.

As you continue to explore and reflect on the Greenwood community, take a few minutes to view this short video from the Smithsonian Channel.

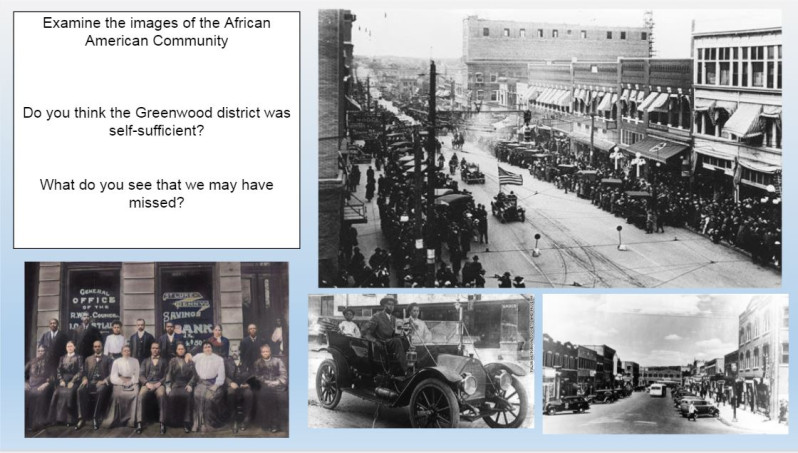

Review the images on Jamboard 5, sharing scenes of Tulsa's Black Wall Street before the 1921 massacre. Look at the community, and analyze the buildings, cars, cleanliness, and resemblance to other towns in the United States during that time period. Answer the following questions on Jamboard 5 using sticky notes.

- Do you think the Greenwood district was self-sufficient?

- Should this town be labeled Black?

- Can you list any details that make it a Black town besides the occupants?

- Do you think the white citizens in Tulsa believed the African Americans in the town followed that unspoken “racial etiquette” as a social structure?

- Could the white citizens see the Black citizens as subservient to them, or did they move beyond the life of a former slave?

Explore this NYTimes visualization of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Look closely at the types of businesses and the community members who lived and worked there.

- What businesses or services did you find surprising or interesting?

- What businesses or services were not observed, if any?

- What do you see that we may have missed?

The alleged breaking of the unspoken “racial etiquette” is how the Tulsa Race Massacre began in 1921. Analyze this image on Jamboard 5, and review the number of Black businesses they created. Compare these to the NYTimes visualization.

Think about the time period and the obstacles that Black citizens faced to achieve home and business ownership. Think about their dress, grooming, and surroundings as viewed in the image and respond to these questions on Jamboard 6.

- Did this community become self-sufficient despite the obstacles of segregation?

- How much control did these rules give to white Americans

- How many of these rules are common in today's society?

Read through some of the “racial etiquette” norms and use a sticky to respond to these questions on Jamboard 7.

- Are Black people treated as equal citizens?

- Which “racial etiquette” norm do you find odd or most interesting?

- Did the people of Greenwood district live by these norms?

The enforcement of Jim Crow policies reinforced the beliefs of that time that whites were superior to Blacks in all important ways, including but not limited to:

- intelligence, morality, and civilized behavior.

- dating between Blacks and whites would produce a mongrel race, which would destroy America;

- treating Blacks as equals would encourage marital unions.

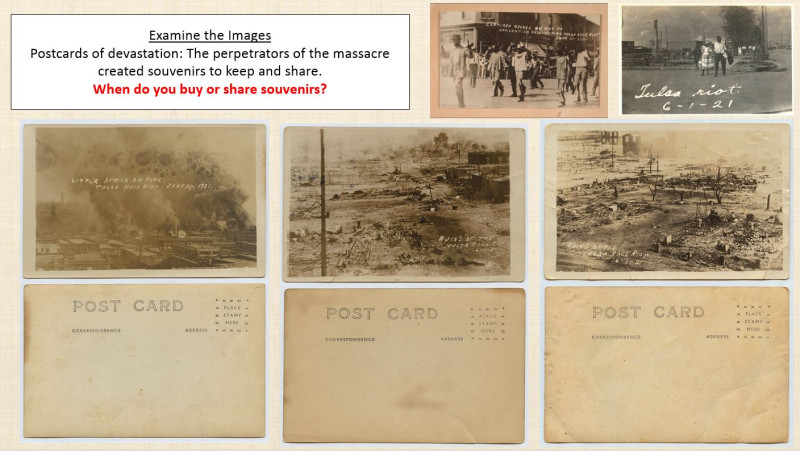

Jamboard 8 illustrates the devastation of the Tulsa Race Massacre through “souvenir” postcards. Analyze each postcard image.

- When do you buy or share souvenirs?

- What do you think of using postcards as a memento of a violent act?

- Would you send this postcard image to a loved one?

- Can you think of more recent examples where these types of images were shared?

The assailants created a collection of postcards to mark the historic violence in Tulsa. Use a sticky note; compare the postcard images with the previous slide on Jamboard 6 of the thriving town.

Do you think the assailants destroyed the lives of the Greenwood residents?

Return to the NYTimes visualization and examine the section entitled, “The Massacre That Ended it All.” Read the account of the exchange between two teenagers, Dick Rowland and Sarah Paige, which resulted in the arrest of Mr. Rowland. Once in custody, the vigilante behaviors within the town began the massacre in Tulsa.

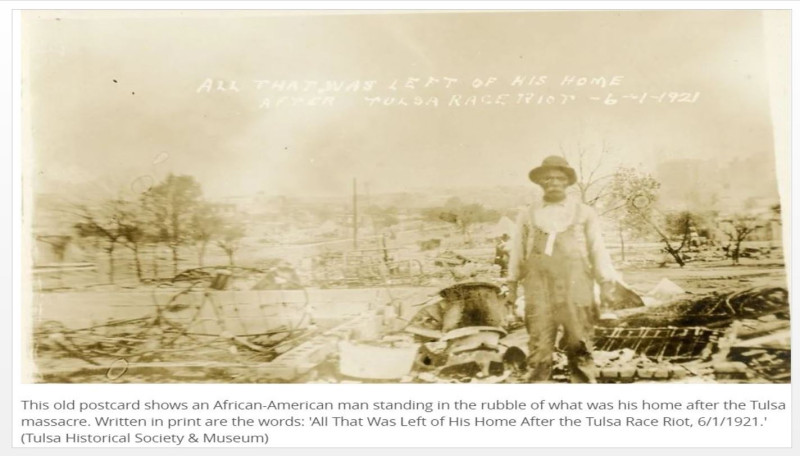

Examine the image on Jamboard 9 of the Tulsa Race Massacre, and review the writing on the postcard about the incident. Use a sticky note to answer the following:

- Do the words written on the image show remorse?

- Explain your answer.

- How might the man in the image respond to those creating and selling the souvenir postcard?

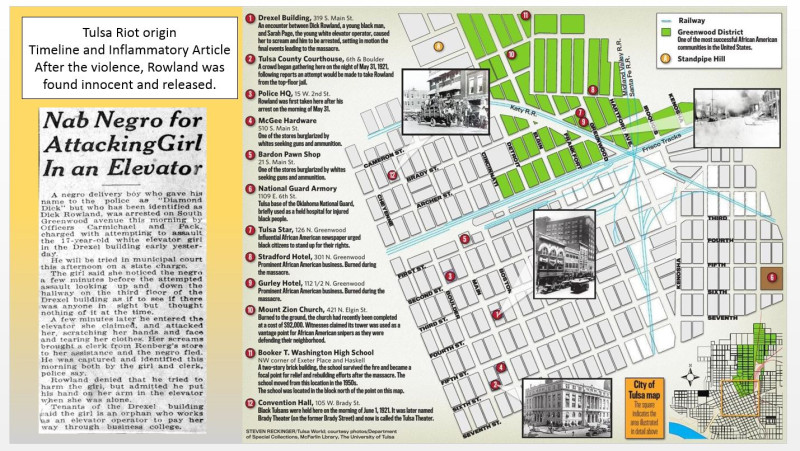

Jamboard 10 includes a newspaper article and map of Tulsa with a timeline of events leading up to the massacre and destruction of the Greenwood district. Read and respond to the questions below using a sticky note on Jamboard 10:

- Did the arrest of Mr. Rowland lead to the vigilante destruction of Greenwood and the Tulsa Race massacre?

- What role did the Black WWI veterans play in defending Mr. Rowland’s rights to due process in trying to protect him? (Use Jamboard 9 and the NYTimes visualization.)

- After viewing the massacre postcards on Jamboards 8 and 9, and the timeline and visualization, summarize your thoughts about the citizens of the Greenwood district — were they given justice?

The Black citizens were seen as agitators after asking for due process and legal justice for Dick Rowland. The white citizens retaliated against the Greenwood District, seeing the call for due process as a breaking of the racial code. The white newspaper published an inflammatory headline about the incident. Within two days, the rioting began. The white vigilantes dropped gasoline bombs on the community, burning thousands of people out of their homes, deputized white men to assist in the burning and looting, and buried their victims in mass graves.

This video and the image on Jamboard 11 further details the timeline and gives a first-person account of how the riot happened.

You will listen to the testimony of 107-year-old Ms. Viola Fletcher; the oldest living survivor of the Tulsa race massacre, who testified before Congress on May 19, 2021. Eyewitness accounts are a primary source, and when she is no longer living, her testimony of the crime will live on in the film as documentation of the horrors of that day.

View the testimony of Viola Fletcher and share your thoughts on her story on Jamboard 11.

- What did you learn from her words?

- How important are first-person narratives and testimonies as primary sources when learning about history?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers as an exit ticket.

Explain:

How did imposing debt bondage maintain the status quo during the post-Reconstruction era?

Did the prosperity of the Greenwood district threaten the economic balance of power between Black and white citizens of Tulsa, contributing to vigilantism and eventually leading to the 1921 race massacre? The white former slaveholders were desperate to maintain a system as close to that of the free labor, agricultural wealth, and previous caste status that existed before the Civil War. This form of debt bondage was a way for them to try to maintain the status quo during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era. This was true In cities across the country, not just in Tulsa.

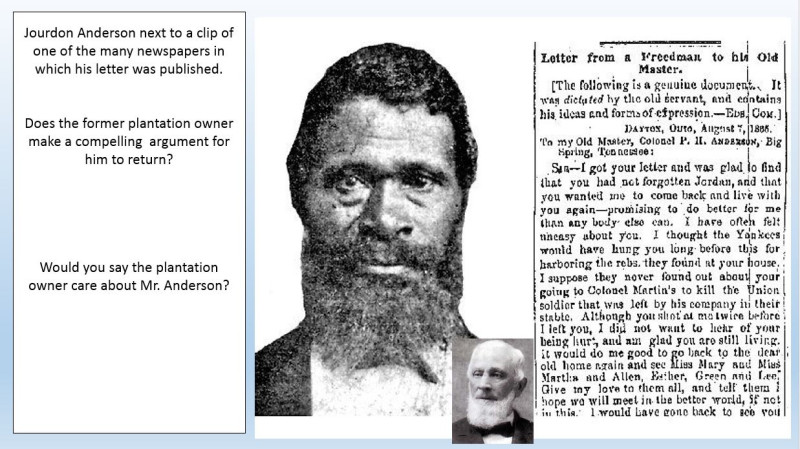

Review Jamboard 12, including an article from Jourdan Anderson to his former master, that appeared in a Cincinnati newspaper in 1865, and was widely published in other papers across the country. Read the entire letter using the link provided, and record your answers on a sticky note on the Jamboard:

- How do you think former slave masters like Col. Anderson felt about Black Americans creating their own personal wealth and businesses?

- What part of Mr. Anderson’s response did you find most surprising or interesting? Why?

- How did Mr. Anderson arrive at the sum of money he requested in compensation for wages owed?

- How does Mr. Anderson use sarcasm to refuse his former master’s request? Give one or more examples.

For more information on debt bondage in the modern era, you may review this report from the United Nations, as archived at the Library of Congress.

Once freed, African Americans during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era wanted to find their own spaces to live and flourish. Land ownership was a contributing factor to the success of the Greenwood community. The 1866 United States Treaty with the Cherokee Nation allotted 160 acres of land to the formerly enslaved Africans owned by members of the Cherokee tribes. These citizens frequented the Greenwood district, adding to the economic growth of the area. Read a transcript of this primary source here and view the map.

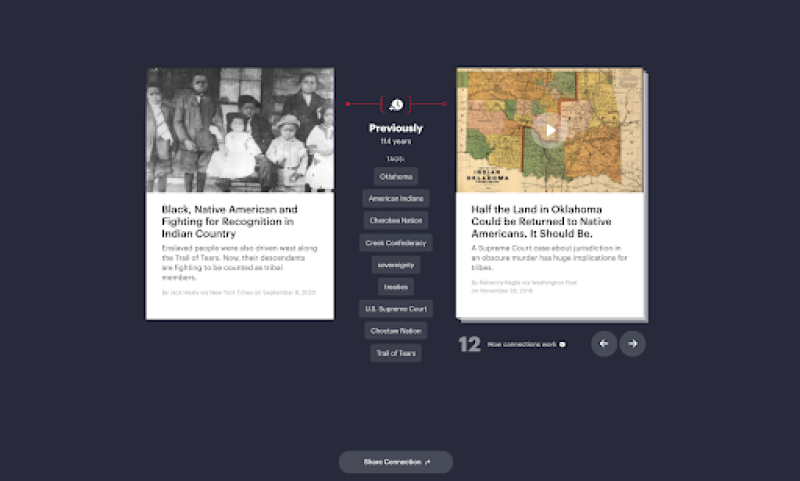

Review this Bunk Connection to learn more about the treaty and the African Americans’ connections to the Greenwood district. Take time to read both excerpts and explore the different tags that connect the two articles.

- What did you find most interesting or surprising about the excerpts you explored in Bunk?

- What new “Tag” might you add to connect the two excerpts based on our reading?

- Where might you find more information about this topic?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers as an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

How did Jim Crow era government policies and local newspapers encourage the vigilantism that started the Tulsa Race Massacre?

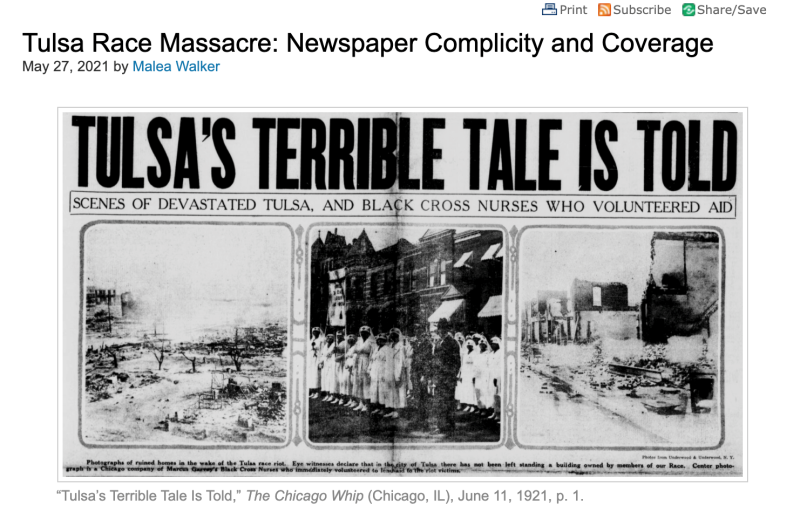

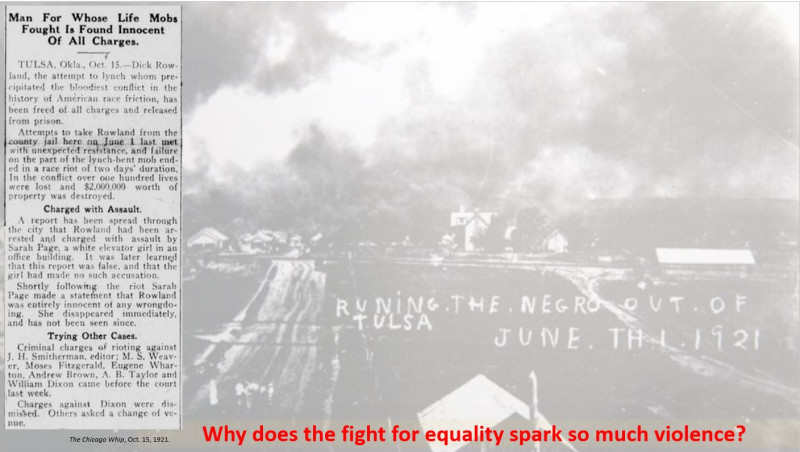

The local newspapers covered the arrest of Dick Rowland extensively. This collection of articles from the Library of Congress shares several examples of how the story was exaggerated, and how the media contributed to the hysteria among the white community. Little coverage, in comparison, was offered after the massacre, when Mr. Rowland was found innocent and released, freed of all charges.

Read this article, dated October 15, 1921. It is included in the LOC collection and on Jamboard 13.

According to the article, Rowland was freed of all charges and let go following the massacre. Using a sticky, add your responses to the following questions on Jamboard 13.

- Why do you think this story received less coverage in the local newspapers?

- Why does the fight for equality spark so much violence?

- Why did the United States government allow Jim Crow laws in the states and localities?

- How has the role of media changed as new forms of communication, including social media, have evolved?

The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson's landmark Supreme Court decision allowed segregation to continue into the next century, until the 1954 Brown v. Board decision. For more information about the historical background from this era, take a few minutes to explore Jim Crow and Segregation from the Library of Congress.

By 1890, Mississippi added a disfranchisement provision to its state constitution, limiting or creating barriers to the voting rights of men of color, legalizing Jim Crow. They were a patchwork of state and local laws, codes, and agreements enforced across the nation in many towns and cities, including local ordinances. They designated white and Black neighborhoods, using unwritten agreements among real estate interests maintaining residential segregation in the form of restrictive covenants.

African American men were denied the right to vote with the passage of poll taxes, unfairly applied literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and other unjust barriers. Signs were used to associate Jim Crow rules – "Whites Only," "Colored"– appearing at bus stations, water fountains and restrooms, the entrances and exits to public buildings, hotels, movie theaters, arenas, nightclubs, restaurants, churches, hospitals, and schools. Interracial marriages remained outlawed, and the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, gave women the right to vote, further restricted the rights of more people of color.

Segregation was often maintained by violence, white supremacy, and in some cases by law enforcement officers and elected officials. Armed white mobs and violent attacks by anonymous vigilantes citizens became more common. Black Americans had no legal recourse against these assaults, the United States criminal justice system was predominantly white, including most police officers, prosecutors, judges, juries, and prison officials. Violence was normalized and used to enforce Jim Crow violations. It was a method of social control, and the most extreme form of Jim Crow violence was lynchings.

Using Jamboard 14, view images from the Jim Crow era. Select one primary source that reflects racial segregation or considers segregation from multiple perspectives.

- How might someone living during this time feel excluded?

- How might they feel if they were not excluded?

- What might they do if they were asked to enforce these rules or laws?

Analyze 2 or more primary source images from Jamboard 14 that illustrate the Jim Crow era.

- How did Jim Crow laws justify these policies as a benefit to the community —either to whites, to people of color, or both?

- What is meant by the term “separate but equal?”

- How is this concept related to the arguments used to pass Jim Crow laws?

Read some of these examples of Jim Crow laws from Ferris University’s Jim Crow Museum website. Be sure to explore examples from more than one state.

- What do you notice about the content of these examples comparing two or more states?

- What patterns do you notice?

- What do you think would happen if one of the rules of the unspoken social etiquette were broken?

The Jim Crow laws and unspoken social etiquette were supported by the constant threat of violence. Blacks who violated Jim Crow norms, for example, drinking from the white water fountain or trying to vote, risked their homes, their jobs, even their lives. Whites could physically beat Blacks with impunity, they faced no legal consequences. The Blacks had no form of protection from the violence, usually, the law enforcement officer in the area endorsed the local violence. The principle rule of Jim was grounded in inequality if you did not follow the rules, you could pay with your life. Although free, they would never be equal to a white person and did not deserve the same rights or social regard as a human. Previously viewed as property, per the US Constitution, Blacks were labeled as 3/5th a person, whites wanted African Americans to remain in their previous subservient role. Violence became a consistent tool for controlling African Americans.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

How does our thinking change about Contested Landscapes?

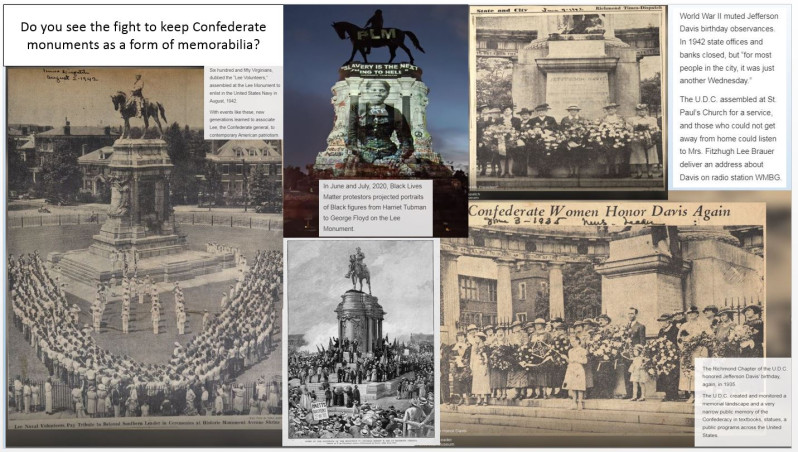

Almost as soon as Confederate statues and monuments began to appear across the landscapes of the Jim Crow south, they were topics of great debate and controversy. During the early 1900s, remembrance celebrations and fundraising campaigns were held around the creation of Civil War statues and ongoing public gatherings of adulation and homage, and not just in the former seceded Confederate states. Perhaps one of the largest concentrations of Confederate iconography was Monument Avenue, located in Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the Confederacy.

Jamboard 15 includes pictures from past and present gatherings along Monument Avenue. In erecting those statues, for many these images were not memorials, but a reminder of violence, intimidation, and enslavement. Take a few minutes to view each image of these contested landscapes, and read the captions of the images provided, or additional images from On Monument Avenue, including virtual exhibits from the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia.

During the summer of 2020, after the murder of George Floyd and a period of civil unrest, through the fall of 2021, the remaining Confederate Monuments on Monument Avenue were removed, and in some cases relocated by local and state government officials, after lengthy court battles and legislative actions. Monuments in other cities across the country were removed earlier, or are in the process of being removed, as well as the renaming of public buildings, military bases, public, and private institutions, and professional sports teams.

- Do you see the fight to keep Confederate monuments and memorials as a form of memorabilia or patriotism to this era?

- As our thinking changes about Monuments and Memorialization, more and more statues, buildings, first-person and military bases are being removed or renamed across the country. How does this change the physical and cultural landscape of a community?

- What different methods – or approaches – of opposition can you identify?

- As our country's population becomes more diverse, and the evidence from this time is examined, do these celebrations mirror the ideals of our country?

- Is the removal of statues, or renaming of streets or buildings “erasing history,” or are communities basing these decisions on learning a more complete and honest narrative of history, and by interpreting new scholarship?

Brainstorm other forms of protest not shown in these primary sources, and look for examples in either historical collections, current multimedia, or your local community. Are there buildings, statues, or other contested landscapes in your community you might research and explore?

Once you have researched your topic, make a copy of the Eduprotocols Sketch and Tell slides template, completing it as you discuss and share your research with your class. Your teacher may provide further guidance on how to copy and share your slides for face-to-face or virtual presentations.

Citations

American Civil War Museum “Birth of Monument Avenue.” Accessed December 17, 2021. https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/exhibit/0QLiK5dKZ1esJA?hl=en

Black Past “1866 Treaty with the Cherokee Nation” Accessed July 10, 2021 https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/u-s-treaty-cherokee-nation-1866/

Black Past “Ida B. Wells, “Lynching, Our National Crime.” Accessed July 10, 2021 https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1909-ida-b-wells-awful-slaughter/

Black Past “Ida B. Wells, “O.W. Gurley” Accessed July 10, 2021 https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/o-w-gurley-1868-1935/

"Brown v. Board of Education Topeka." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases. Accessed 23 Nov. 2021.

“Dick Rowland is Freed of All Charges,” The Chicago Whip, Oct. 15, 1921.

Ferris State University “Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia.” Accessed July 8, 2021 https://www.ferris.edu/htmls/news/jimcrow/links/misclink/examples.htm

Ferris State University “Jim Crow Etiquette-September 2006.” Accessed July 8, 2021 https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/question/2006/september.htm

"Loving v. Virginia." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases. Accessed 23 Nov. 2021.

PBS “Reconstruction America after the Civil War.” Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed July 18, 2021 https://www.pbs.org/weta/reconstruction/timeline/

"Plessy v. Ferguson." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

Seizing Freedom “They Can't Keep Us Out”. Accessed July 8, 2021 https://seizingfreedom.vpm.org/

Smithsonian Channel “Footage of the Prosperous Greenwood and the Tulsa Massacre.” Accessed January 4, 2022 Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ca7lI6wT9MI

Southern Journey: Migration of the South, 1790-2020. Accessed November 7, 2021 https://dsl.richmond.edu/southernjourney/

Smith, Trevor. “Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood wasn't America’s only Black Wall Street.” Surdna Foundation Accessed January 18, 2022 https://surdna.org/news-insights/tulsas-greenwood-neighborhood-wasnt-americas-only-black-wall-street/

Tulsa Historical Society and Museum “Postcard Images.” Accessed July 10, 2021 https://www.tulsahistory.org/

Tulsa World. “107-Year-Old Tulsa Race Massacre Survivor Viola ... - Youtube.” YouTube. C-SPAN, Accessed May 19, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZV8_nAQ2ys

Walker, Tim. “It happened here Duluth residents face the painful lessons of a 1920 Lynching” Learning for Justice. Issue 24 Fall 2003. Accessed December 17, 2021 https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/fall-2003/it-happened-here

Seizing Freedom Credits:

Seizing Freedom is a co-production of VPM and Witness Docs from Stitcher. Host: Dr. Kidada WilliamsLead Producer/Writer: Joshua MooreLead Editor: Kelly JonesAssociate Producer: Ronald Young, Jr.Interview Producer: Lushik WahbaSound Designer: Jakob Lewis & Cariad Harmon of Great Feeling StudiosComposer: Dan Burns (Additional Music from Blue Dot Sessions)Project Manager/Editor: Gavin WrightExecutive Producer: Ed AyersVoice Actors: Andre Giles, Andrew Robinson, Candice Holley, Chiquita Melvin, Conrad Haynes, Constance Swain, Dale Leopold, Dave Gau, Eric Holloway, Fiona Soul, Frank Harrison Jr., Gavin Wright, James J. Johnson, Jefferson A. Russell, Joshua Moore, June Jones, Justin G. Reid, Louis Hampton, Marcia Baker, Ozzie Wilson, Paul Schmidt, Peter Jacobs, Rachel Dilliplane, Richelle Claiborne, Ronald Young Jr., Sierra Doss, Terry Menefee Gau, Tim Jenkins, William Barnett, Xavier Taylor, Yvette Carmen.

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc