This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

The Fire of a Movement

View Student Version

Standards

C3 Framework:D2.His.3.6-8. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to analyze why they, and the developments they shaped, are seen as historically significant.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

National Council for Social Studies:Theme 2: Time, Continuity, and Change

National Geography Standards: Standard 9: The characteristics, distribution, and migration of human populations on Earth's surface

Teacher Tip: Think about what students should be able to KNOW, UNDERSTAND and DO at the conclusion of this learning experience. A brief exit pass or other formative assessment may be used to assess student understandings. Setting specific learning targets for the appropriate grade level and content area will increase student success.

Suggested Grade Levels: Middle/High School

Suggested Timeframe: 3 sessions, 90 minutes each session.

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet, or mobile device, optional: sidewalk chalk

Key Vocabulary

Acquitted - to declare not guilty of a crime in a court of law

Ancestor - a group of people related to a family from an earlier generation

Bookkeeper - a person who manages financial records for a business

Commission - a group of citizens asked to perform a task or provide advice

Conscience - a person’s inner sense of right or wrong

Descendant - a person related to a group of people with the same ancestors

Diaspora - a community of people with a common background and beliefs scattered from their homeland

Disaster - a sudden event causing great damage and suffering

Flammable - able to catch on fire very quickly

Immigration - to move to a new country

Indicted - to formally accuse someone of a crime in court, after examining evidence

Industrialization - an economic activity that turns raw materials into manufactured goods

Ingenuity - to be clever, skilled, and resourceful

Legacy - property or money handed down from generation to generation, or a historic accomplishment or which came from a previous generation

Manslaughter - the crime of causing death without planning or meaning to do so

Manufacturer - a company that uses machines to make a large number of items in a factory

Needle trade - a job or business that is involved in making clothing

Oratorio - a choral work performed with an orchestra that tells a story

Reckoning - to pay a debt, or to be held accountable for one’s behavior

Regimented - strictly controlled

Shirtwaist - a simple button-down women’s blouse styled for the workplace or public wear

Sweatshop - a business with a large number of employees, often working for low wages and in unfair and/or unhealthy work conditions

Tenement - an apartment building, often in a low-income neighborhood

Wary - careful, alert, not easily trusting

Urban - having to do with a city or town

Workplace - a business location where people gather to do work, such as a factory, office, or store.

Yiddish - a language related to German, Hebrew, and a combination of other elements, originally spoken by Jews from central and eastern Europe, and their descendants

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tip:

This Learning Resource is developed in collaboration with New American History, Virginia Public Media, and Field Studio, producers of The Future of America’s Past.

Always view all videos, listen to all audio clips, and review hyperlinks before teaching the lesson to ensure they are operable, age-appropriate for your class, and do not present a challenge for any of the social or emotional learning needs of your students. Topics concerning tragedies such as 9/11, a fire, or the death of young people may be a trigger for some students. Some students who are immigrants or refugees may also have experienced trauma or be fearful of reading about or viewing images of the victims of the fire, or the way immigrants have historically been treated or lived. Educators must exercise their best judgment and build on prior trust relationships developed with their students as they use these learning resources in whole or in part.

This Learning Resource includes language in the body of the text to help adapt to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

A variety of mostly or always free web-based educational tools are recommended as possible ways for students to channel their learning in ways that enable them to think critically and creatively while honing their historical thinking and communication skills, including the use of social media tools such as TikTok and Instagram and learning management systems such as SeeSaw, Canvas or Google Classroom. As always, the classroom teacher should set age-appropriate parameters, parent or guardian approved and aligned to the school’s technology acceptable use policies.

This Learning Resource follows a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience, or as part of a sequence of learning experiences using all the segments from the same episode of The Future of America’s Past. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of the students and the curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

For Students:

This Learning Resource explores the largest and most tragic United States workplace disaster of the 20th century, known as the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. While few eyewitnesses or survivors are still alive, the legacy of the sacrifices made by these victims remains in our modern-day public safety standards for schools, workplaces, and other public spaces. In discussing this topic, it is important to be respectful and aware of these losses and the contributions of the victims to the health and welfare of all citizens today.

Engage:

How did the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire raise public awareness of unsafe work conditions in America’s factories?

In school, we practice fire safety drills, and on airplanes and in movie theaters, we note the nearest fire safety exits before takeoff or viewing a film. Today, schools, workplaces, and public buildings are routinely inspected for safety features and other prevention measures such as working fire extinguishers and smoke detectors. Many of these practices came about after the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911. (View video segment, “A Haunting Tragedy.”)

Take a few minutes to review the vocabulary list either on your own (if working remotely) or with a partner. What words are you already familiar with? Which did you hear in the introductory video? As you move through viewing additional video content and learning experiences, think about how these words are integrated.

- Which words are based on legal terminology?

- Which words are based on geographic themes?

- How else might you categorize these words?

During the spring of 2020 schools and businesses on almost every continent closed down during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Students and teachers worked hard to continue teaching and learning remotely, and some adults adapted to work remotely from home. Many adults who are “essential workers” were on the front lines working in hospitals as first responders or were keeping the supply chain moving in grocery stores, farms, warehouses, sanitation facilities, and transportation. Teachers adapted and learned new ways to teach remotely. Many of these workers belong to labor unions or organizations that work with employers to ensure their workplace is safe and prepared for most emergencies. This was not always the case in the history of America’s workforce and industries. (View video segment, “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire.”)

Elissa Sampson, an urban geographer, shares the horrific story of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire with historian Ed Ayers, detailing the many ways the survivors of the fire and other immigrant workers pushed for workplace reforms. Their advocacy and the public outcry resulted in numerous legislative actions designed to prevent future tragedies like the events of March 25, 1911.

Take a few minutes to explore this site and review the links about the legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, including the links to the legislative reforms and responses from the labor unions. Turn and talk to a partner, or if working remotely your teacher may use videoconferencing to provide opportunities to use the online chat feature or work with classmates in breakout rooms to discuss the following questions:

- How did people in New York City react to the news of this tragic fire?

- Was the fire avoidable?

- Describe one or more of the new laws passed to help prevent future workplace tragedies

- Explain the role labor unions play in negotiating and advocating for workplace safety and reforms.

- How are workplace safety decisions being made during the current global pandemic?

- How are school systems deciding whether learning should happen in-person at school or remotely?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

What lessons might we learn from the stories of the families of the victims, survivors, and witnesses of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire?

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire prompted many legislative and workplace-related reforms that still help keep workers safe. But there is also the human side of the story which, like most tragedies, can often get lost in media coverage that follows political or social unrest. Instead, these stories are remembered by the friends and family of the victims and are an important part of history. (View video segment, “Remembering Ancestors in the Triangle Fire.”)

“I love the idea of a memory getting stronger rather than weaker over time.”

“Yes, yes, and you know it's a strange irony, they're getting what I didn't get, they're getting the full story.”

Think about a memory you have or a story of a shared experience your family often tells which seems to get stronger as you get older. Do you have certain memories from your childhood that, as you have grown up, your family may remember differently? Is there a story they have told you about yourself that you were too young to remember? Take a few moments to jot down your ideas about these memories. Explore the quotes from historian Ed Ayers and descendant Suzanne Pred Bass about the way her grandchildren are now learning about the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.

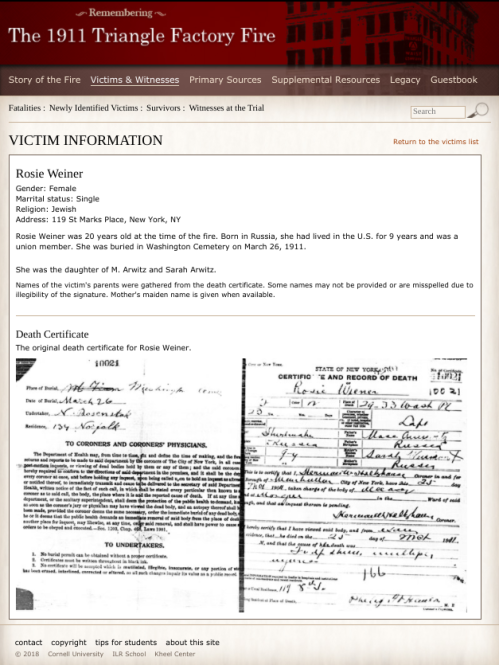

Explore some of the stories of the victims of the fire, like Rosie Weiner. Explore survivor or witness testimonies. Think about the following:

- Have you ever learned something new about history which contradicted or seemed different than the way you learned it in an early grade level?

- Why do you think this happens?

- How might you discover the “truth” or find out the best way to look at a historical event or source?

Add these thoughts to your reflective journal. You may also share your thoughts with us via email at editor@newamericanhistory.org or share via social media (links on our pages) if your teacher or family allows. Be sure to tag us as you share!

Immigrant families like the Weiners often lived in crowded tenements, which were also the site of sweatshops as we learned from the interview with urban geographer Elissa Sampson. Life for the families of the workers who perished in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was often a challenge as we learn here with a visit to the Tenement Museum (view video segment, “Tenement Life in the Time of the Triangle Fire.”)

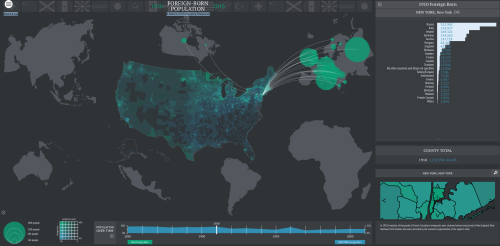

Take a few minutes to explore the Foreign-Born Population map, based on Census data from New York City. Think about what you have learned about families like the Weiners and Rogarshevskys.

Notice the slider tool near the button of the map and the bar graph on the top right corner. Use the down arrow to scroll through the list of where immigrants living in New York City during this time may have originally immigrated from, and use the inset map to compare New York City in 1910 to other parts of New York. Notice how the map changes as you move the slider tool by decade.

Find the city/county where you live or find the location of your school using the search box. Compare the map to the 1910 data and to the most recent 2010 map.

- What do you notice?

- How does the map/graphs change as you change the year or location?

- In 2020 a new Census is collecting data on the current population of the United States. What predictions might you make about the way the map will change based on this more recent data?

You may have friends or family members who are recent immigrants from some of the locations shown on the map. Share your results with an elbow partner or if working remotely, in a group forum or chat as directed by your teacher. You may also share your thoughts with us if your teacher or a trusted adult permits. You may email us at editor@newamericanhistory.org or share via social media (links on our pages) if you are age 13 or older. Be sure to tag us as you share!

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

In what way does the media play a role in the public’s perception of tragic events, and how can they help shape public reforms?

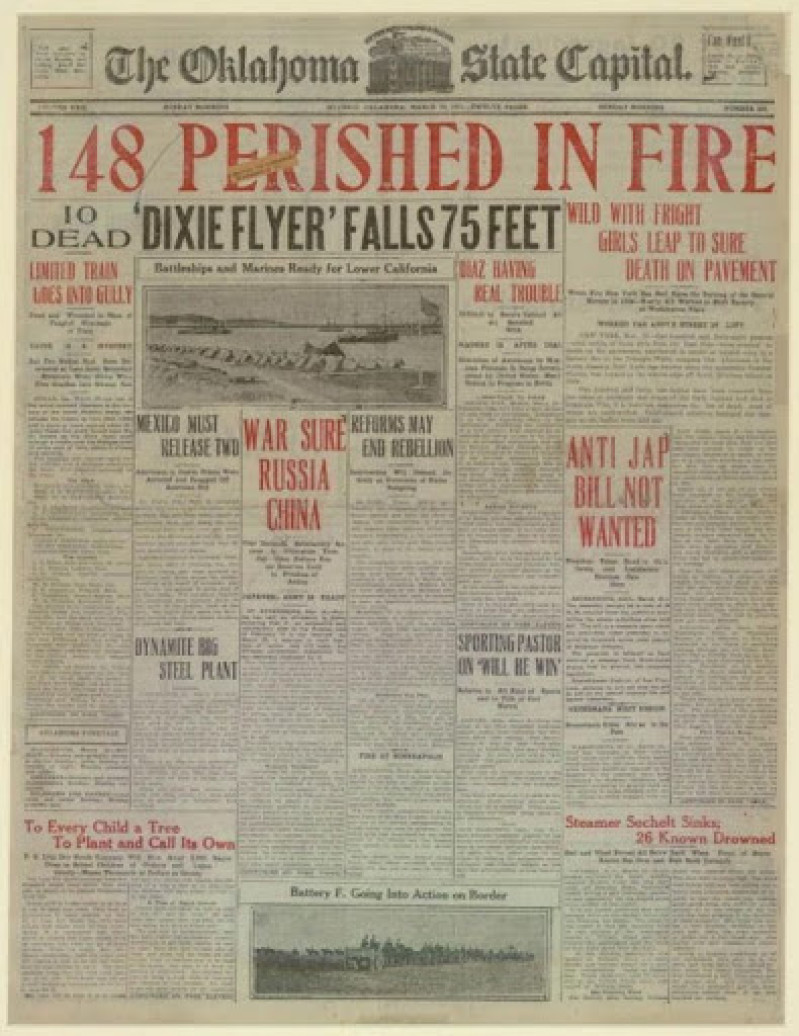

Many of the friends and families of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire learned of the tragic events of March 25, 1911, and later followed news of the trial, by reading a local Yiddish newspaper, The Jewish Daily Forward. Archivist Chana Pollack describes the way local journalists shaped the story, and how language can hold a deeper meaning for those reading about their loved ones in particular. (View video segment, “Triangle Fire Journalism.”)

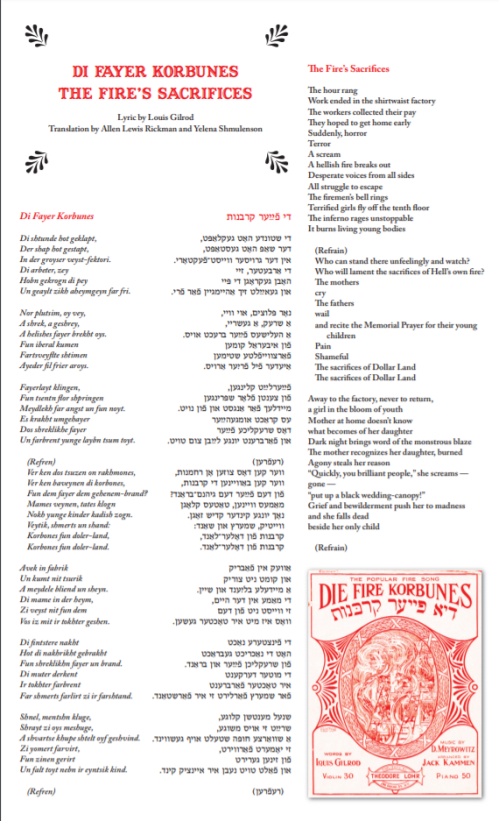

“The Morgue is Full with Our Victims," but it's an interesting choice of a word for victims in the Yiddish is drawn from the traditional Hebrew word for sacrifice. So it's a very poignant kind of headline. They set the stage for how they're reading the story. And how they're relaying it is that the entire Jewish neighborhood is in mourning.”

- How does the journalist’s choice of the word ‘victims” translate differently for Jewish readers? Why do you think the writer chose to make this connection?

- In what ways did translating the news of the fire into English expand the depth of the newspaper’s coverage of these events?

- What service did the newspaper provide in assisting the families, medical professionals, and other authorities with identifying the victims and survivors?

- Thinking about other tragic events, such as 9/11 or the COVID-19 global pandemic, how has the role of the media changed over time in the ways it reports tragic events?

Examine these headlines from 1911 from newspapers across the country. The first is from The Jewish Daily Forward, the Yiddish newspaper mentioned in the video. Read the full transcription here. Next, take a look at how other regions in the United States reported the story by looking at examples from the Library of Congress and Chronicling America.

Compare and contrast how each front page of the newspapers describes these events.

- Compare the headlines: what similarities and differences do you notice?

- How is the story reported in cities or states outside of New York?

- Does the distance from New York seem to influence the way the story is reported? If so, how are they different?

- Do any of the details in the headlines or stories seem to have similar or different facts or details?

- How might you explain the differences, if any?

- How did media coverage of later tragedies such as 9/11 or the COVID-19 global pandemic differ?

How would you have reported on the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire? Create a headline and write a brief news report. You may use information from the newspapers you viewed from the Library of Congress, or select one of these audio interviews with eyewitnesses to the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, published by History on the Net, as part of your news report. Submit your report as directed by your teacher.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

In what ways might art help heal, inform, or unite our communities in times of tragedy or outrage?

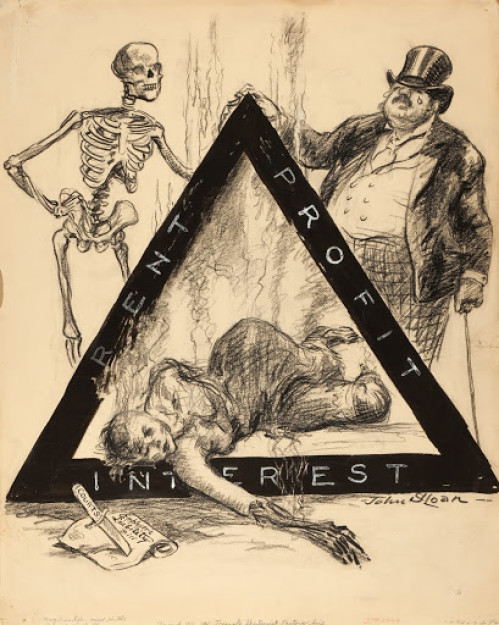

The owners of the Triangle Waist Company were indicted on charges of manslaughter for the deaths of their employees. Despite eyewitness testimonies and evidence that their negligence and unsafe workplace conditions contributed to the loss of numerous lives, in the end, they were acquitted and allowed to collect a large sum of money as part of an insurance claim. The victims’ families, employees of the garment industry, other immigrant families, and citizens across the globe were grieving and outraged. Many turned their anger into activism, protesting and demanding reforms in workplace safety, building codes, and health regulations from the city, state, and eventually federal government agencies. Read this report about the changes that improved the working and living conditions for immigrants working in garment factories and, eventually, in many other labor industries and workplaces, after the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.

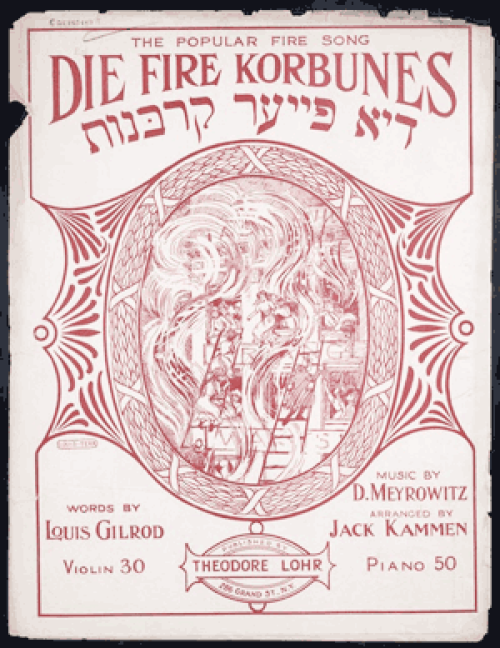

Another way people express their grief, in addition to leading protests and engaging in activism, is through the healing power of art and music. Following the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, numerous pieces of music were composed, poems and stories were written and works of art were created. An earlier piece of music, Die Fire Kokrbunes, was written shortly after the fire in 1911 and is preserved by the Library of Congress, including the original sheet music and lyrics. A political cartoon, also published in 1911, is one artist’s social commentary on both the tragedy and the lack of legal consequences for the owners of the factory. Analyze either the lyrics to the music or the cartoon.

- What were the most compelling words or phrases in the lyrics or words from the cartoon?

- Why do you think the artist selected these words?

- How did the music or cartoon make you think differently about the previous content you have read or heard about the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire?

Next, you will view a video about Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Julia Wolfe as she shares an oratorio she composed inspired by and commemorating the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. (View video segment, “Finding Words and Music for a Tragedy.”)

Take a few moments to reflect on the powerful music and images seen in the video. You may wish to describe your feelings as they relate to the Julia Wolfe piece either in words, including poetry or prose, or a visualization such as sketching or word art.

Think about a painting, mural, image, poem, or song that made you feel deeply or express emotions in a compelling way. Share this with your teacher or classmates in the way you feel most comfortable doing so.

How might you share this experience more widely with your community or the artist who inspired you? Consider communicating your thoughts and feelings either by creating your own art, or reaching out and sharing the artwork you selected to help others develop an appreciation for the piece. Be sure to include a proper citation when sharing others’ artwork.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

How should we remember the lives and legacy of people who died because of injustice?

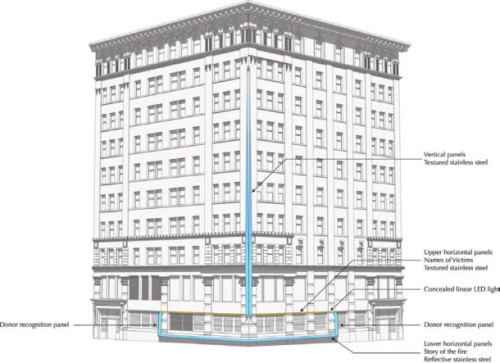

Architects Richard Joon Yoo and Uri Wegman have a vision for how to memorialize the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. Richard discusses their controversial design with historian Ed Ayers in this brief video. (View video segment, “Designing a Memorial, for the Living and the Dead.”)

This diagram gives a closer look at the design for the memorial. Turn and talk to a partner, or if working remotely your teacher may use videoconferencing to provide opportunities to work with classmates in breakout rooms to discuss the following questions:

- What elements of the design are you most interested in exploring?

- How did the architects incorporate historical narratives into the design?

- What other memorials have you seen designed to commemorate a person(s) or event in your community?

- Who decides who and how we memorialize people and events in our community?

Each year the descendants of the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire gather on March 25th to commemorate and honor their ancestors. They are joined by family, friends, local citizens, labor union members, and public officials as they write the names and ages of these often forgotten women on the sidewalks outside their previous homes. Later, they gather at the site of the fire to read their names and ages aloud, remind one another of the power of their memory, and highlight the work still to be done to continue to improve workplace environments for all members of our communities.

Research the name, age, and a brief bio of one of the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire using the map provided. Your teacher may provide sidewalk chalk, or if working remotely from home, you could write on a sidewalk or driveway nearby with chalk. Be sure to practice safe social distancing protocols including wearing a mask and maintaining a safe distance of 6’ or wider. If using chalk and a sidewalk is not an option, think of another creative way you might share this information with your family, neighbors, or classmates, perhaps virtually. Your teacher or parents may allow you to post your work on social media, or on secure school-maintained websites such as SeeSaw, Canvas, or Google Classroom.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

“Die Fire Korbunes or The Fire’s Sacrifices.” Metropolitan Klezmer2019. Metropolitan Klezmer, n.d. https://metropolitanklezmer.com/di-Fire-Korbunes/.

Franklin, Sydney. “N.Y.C. Landmarks Preservation Commission Approves Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial.” The Architect's Newspaper, February 4, 2019. https://www.archpaper.com/2019/01/n-y-c-landmarks-preservation-commission-approves-triangle-shirtwaist-factory-fire-memorial/.

“NEAR CLOSING TIME ON MARCH 25, 1911.” Cornell University - ILR School - The Triangle Factory Fire. Cornell University Kheel Center, 2018. https://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/index.html.

Sloan, John. “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire - John Sloan.” Google Arts & Culture. Google Arts & Culture, n.d. https://g.co/arts/TtnirYPzStbk9eoN8

"The Future Of America's Past: The Fire of a Movement." 2019. TV program. Field Studio. VPM: Virginia Public Media. https://futureofamericaspast.com/.

“The Jewish Daily Forward Reports the Triangle Tragedy.” HIstory Matters, March 22, 2018. http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5482/.

“The Names Map.” Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition RSS. Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition , 2020. http://rememberthetrianglefire.org/the-names/.

“The New York Factory Investigating Commission.” U.S. Department of Labor Seal, 2009. https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/mono-regsafepart07.

“Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: Topics in Chronicling America: Search Strategies & Selected Articles.” Chronicling America. Library of Congress, 1911. https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-triangle-shirtwaist-factory-fire/selected-articles.

View this Learning Resource as a Google doc