This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Unpacking the AHA Report: American Lesson Plan, Part 2

Standards

Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP)

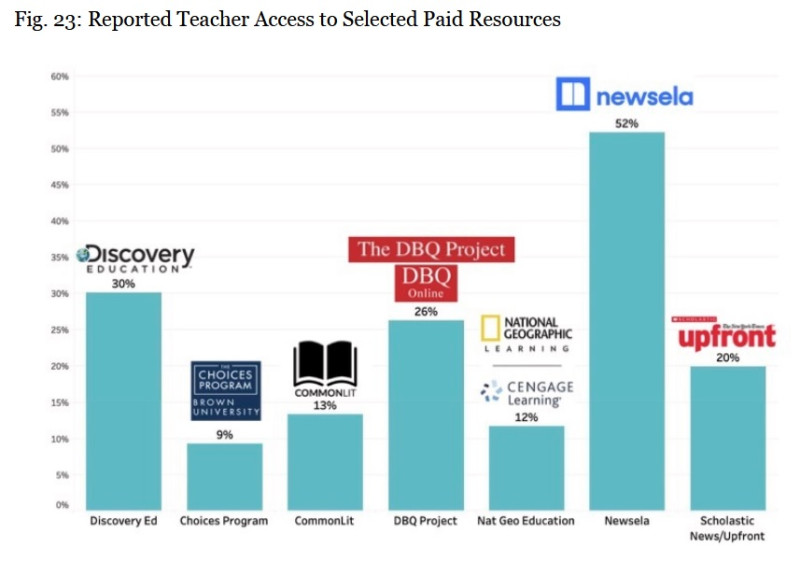

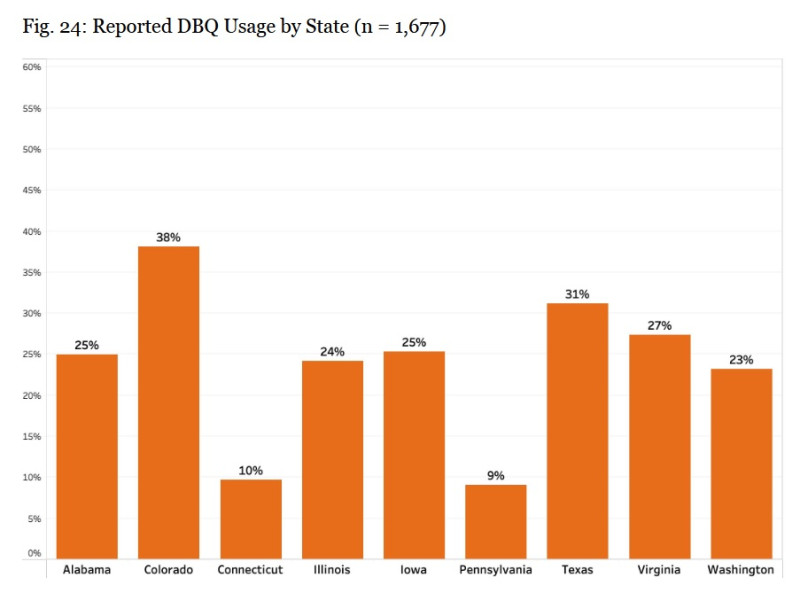

Standard 1: Content and Pedagogical Knowledge Moving on to other resources, there is an understandable focus on what digital or online sources are used, from what entity or institution, and how these are administratively managed. The following graphs are good illustrations of a range that is used. Although there were interesting discrepancies in usage of certain sites between states, the notable names included: Newsela, Discovery Education, and the DBQ Project for paid resources. See Figures 23 and 24 below. (pp 90, 91).

The provider ensures that candidates develop an understanding of the critical concepts and principles of their discipline and facilitates candidates’ reflection of their personal biases to increase their understanding and practice of equity, diversity, and inclusion. The provider is intentional in the development of their curriculum and clinical experiences for candidates to demonstrate their ability to effectively work with diverse P-12 students and their families.

Educating for American Democracy (EAD) Roadmap:

“Supporting deeper history and civic learning for young people has never been more important, and to do that, educators themselves need access to effective professional learning experiences that help them deepen subject matter and instructional expertise and navigate the challenges and tensions of teaching in a complex climate.”

“The aim of the Roadmap is to provide guidance that shifts content and instruction from breadth to depth by offering an inquiry framework that weaves history and civics together and inspires students to learn by asking difficult questions, then seeking answers in the classroom through facts and discussion for a truly national and cross-state conversation about civics and history to invigorate classrooms with engaging and relatable questions.”

Suggested Audience: In-service and pre-service educators

Suggested Timeframe: Could be divided over 3-5 Professional Learning Community (PLC)/planning periods or individual class sessions in an Edu course for pre-service educators.

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet or mobile device

Key Vocabulary

Assessment - the ongoing process of gathering evidence of what each student knows, understands, and can do, usually through exams or graded assignments

Curriculum - refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view of the student's experiences in terms of the educator's or school's instructional goals.

Drill down - examine or analyze something in further depth.

Expository - intended to explain or describe something; it refers to a style of writing that focuses on presenting information and facts about a topic, aiming to educate the reader without trying to persuade them to a particular viewpoint

Historiography - the study of the history and methodology of history as a discipline. Briefly, it is the history of history. Historiography is not studying the past directly, but studying the changing interpretations of past events through historians' eyes.

Ideological - based on or relating to a system of ideas and ideals, especially concerning economic or political theory and policy.

Inquisitive - adjective given to inquiry, research, or asking questions; eager for knowledge; intellectually curious.

Impetus - the force that makes something happen or happens more quickly.

Mandate - (noun) the authority to carry out a policy or course of action, regarded as given by the electorate to a candidate or party that is victorious in an election.

Mandate - (verb) to officially give orders to people or institutions to act or change existing procedures in alignment with particular goals.

Moral Binary - the idea that actions are either right or wrong, with no middle ground. This type of thinking can be useful for simple situations, but it can make it difficult to think critically about complex issues.

Open Educational Resources (OER) - resources available online at no cost to teachers.

Pacing - in teaching, the amount of time given to a range of subjects so that certain areas are covered in the specified timeframe.

Polarization - the act of dividing something into two opposing groups or extremes. It can refer to the separation of people with different beliefs or opinions.

Professional Learning Community (PLC) - a group of educators that meets regularly, shares expertise, and works collaboratively to improve teaching skills and the academic performance of students.

Sociological - concerning the development, structure, and functioning of human society.

Read for Understanding

New American History provides teachers and students with high-quality inquiry-based learning resources for students. We are often also a source for pre-service teacher education and in-service professional learning. In 2024 the American Historical Association (AHA) released a landmark report entitled American Lesson Plan: Teaching US History in Secondary Schools. The main research questions revolved around how history is taught, who is making curricular decisions, and what kind of content is being taught - that is 'What Are Students Learning About Our Nation’s History?’. At issue, unsurprisingly, was whether there was any sense of “indoctrination” happening – i.e. are students getting a view of their nation’s history that is distorted and/or partisan? The basic finding was no. The report is also a good learning tool for educators to think about the current state of history education in America–what we are doing, and why and how.

In this Learning Resource, we continue to unpack some of the more interesting findings from the 200-page report. We offer them as a means to generate conversations and ideas on how we might best innovate and elevate the teaching and learning of American history, geography, and civics amongst teachers and administrators on the front lines making curriculum and decision-making policies and processes.

Note that we have not included a summary of the extensive discussion of historical attempts to control, legislate, or simply study history education in schools. Such discussion is interesting but has a marginal impact on today’s history teachers. If curious, do read pages 29 to 38.

This Learning Resource is a continuation of Part I, and the following discussion assumes you have completed that first Learning Resource.

Engage:

What is actually happening out there?

Part 3 of the Report is “Curricular Decisions”. That is, what curricular decisions are being made, and by whom are they being made?

This is the most content-heavy section of the report, where the researchers dive figuratively into classrooms. Thousands of teacher interviews were combined with the collection of resources in an attempt to understand what is actually happening in US history classes and subject teaching. The results represent the 9 regions / 9 states surveyed. The teamwork or tension between administration and teachers was examined: how do the relationship dynamics affect pedagogy, for example? Researchers also studied the decline of textbooks and the rise of online resources, both free and licensed. Importantly, this section also looks at pressures on history teachers - politics, various controversies, ideological tensions from state and district leadership, as well as issues with parents and local community groups.

The range of questions is too great for this exercise but a few of the key topics we’ve extracted for you include:

- Do standards make a difference in how history is taught?

- When should teachers be required to follow management or administrative directives? When should teachers have the final say?

- How do teachers choose what they must incorporate into curricula vs. what they might safely leave out?

The sections that attempted to answer these questions have snappy titles: “Who’s the Boss?” “No I in Team?” “Credible Sources” and “Vibes and Pressures”.

Administratively, there has been a great deal of growth in administrative staffing across all areas of instruction. Coordination generally was reported as aligned with attempts to standardize social studies, among other subjects. An eye-opening statistic states that since 2000 the number of coordinator positions has risen 155 percent, while teacher staffing rose by only 9 percent. (Further detail can be found on page 69, particularly in the notes section.)

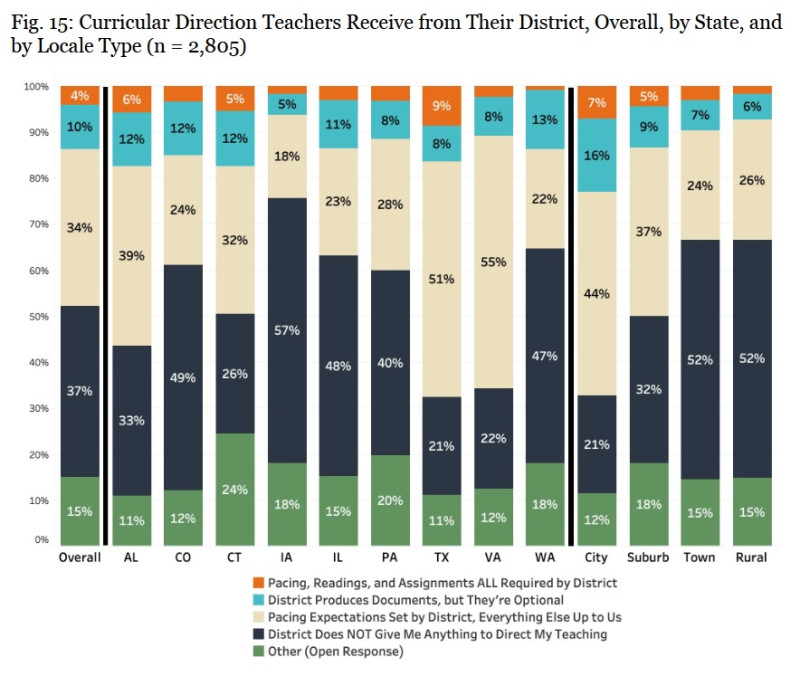

While social studies is seen as lagging in priority behind core subjects, particularly in terms of assessment, there is also a wide variety of coordination roles alongside differing amounts of authority or direction. Check out Figure 15 for some visual data on the topic: (p 70).

This survey data looks at school and district-level control. The following excerpt explains that data:

“At the school level, teacher perceptions of curricular authority also varied across locale type. Sixty-six percent of town and rural teachers said a principal had a role in directing their curriculum, compared with 56 percent of suburban teachers and 55 percent of urban teachers. Suburban and urban teachers reported slightly more emphasis on course teams in curricular decision-making. Seventy percent of town and 65 percent of rural teachers described their course team as influential in their own teaching, whereas 87 percent of suburban and 82 percent of urban teachers said the same.”

The report also includes extensive discussion of the role of administrators and shows that approaches to managing teachers vary widely across environments. For example, rural teachers experience more direction from their principal. Suburban and urban teachers have more experience with course teams/PLCs.

The biggest takeaway from this section is the increase in the administration of social studies, the widely varying levels of perceived or actual power over curriculum, and the mixed reception from teachers on whether they find such management useful or not. Often the bottom line is that administration has no power over what is being taught on a day-to-day basis. A good summary quote on page 74 states, “Ultimately, teachers ride these waves of attention and neglect, while retaining substantial discretion in deciding what they teach, how they teach it, and what materials they use.” A concluding comment suggests that the mixed relationship between teachers and administrators is, in fact, probably an expression of a wider debate: what is the purpose of teaching history?

A discussion could include:

Pre-service:

- When you are a new teacher, will you expect guidance from administrators or fellow teachers? Or do you feel you will function competently without direct guidance?

In-service:

- If pacing is directed by your school or district or above, do you feel this affects the quality of your teaching?

- Do you feel enough time is given for each of the U.S. history topics you have to cover?

Explore:

What do teachers actually use to teach history in the classroom?

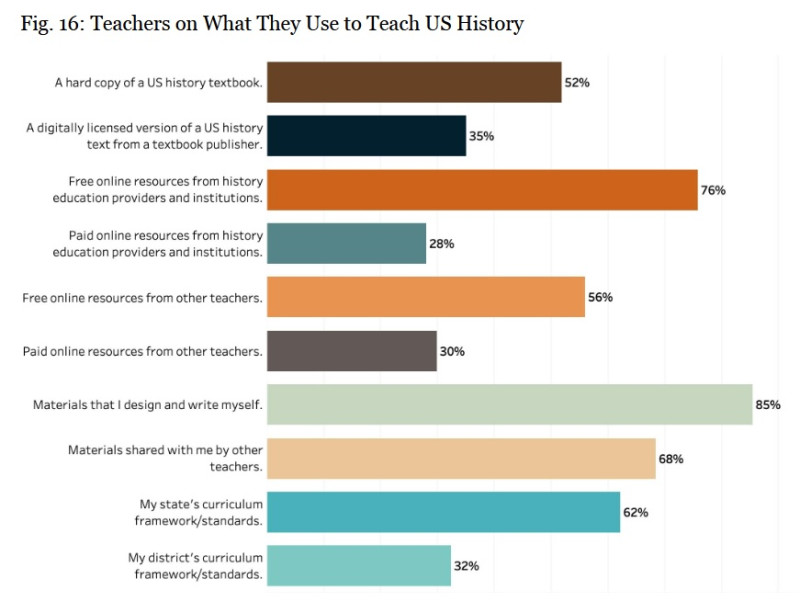

The most common material is self-created by teachers. However, a wide range of source materials are used for teaching resources. Figure 16 shows survey responses. (p 77):

The report then segues into whether teachers are working in teams and how much they collaborate with other teachers. Since this portion of the report moves slightly off-topic from materials for curricular content, it is not included here. It does have several graphs to visualize how much collaboration is happening in the nine survey states. If interested, this information is found on pages 76-85.

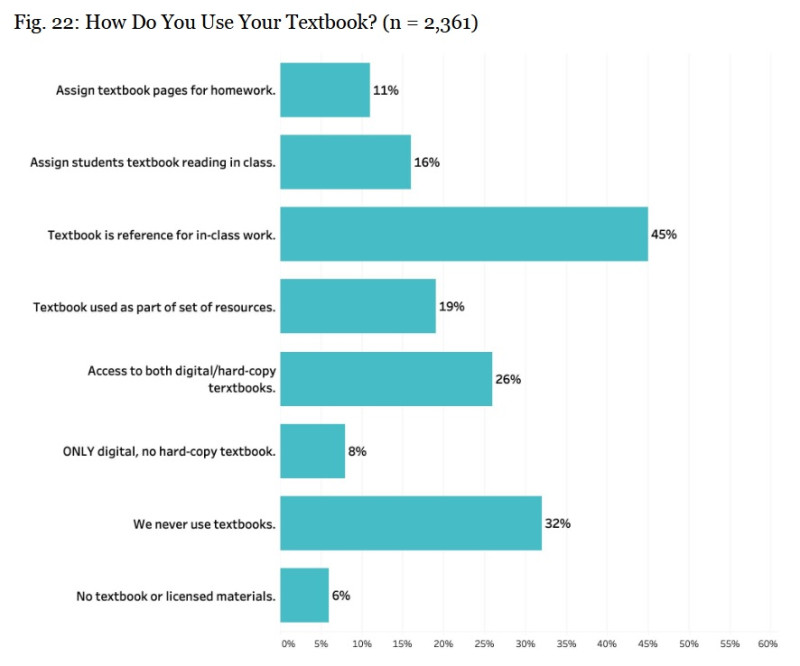

In the next section, on “Credible Sources”, there is an examination of the decline of textbook use and the rise of online and other resources. Almost a third of teachers surveyed said they do not use textbooks. While many still do, the study suggests they function more often as a backup reference. Like other areas surveyed, these answers varied from state to state. Not all statistics were given but the example was the range between Alabama and Virginia, at 63 percent to 37 percent usage, respectively. The report also found that veteran teachers were more likely to use textbooks than newer teachers, with 41 percent of those having five or fewer years in service not using textbooks at all. Figure 22 shows a range of usage responses. (p 87).

Moving on to other resources, there is an understandable focus on what digital or online sources are used, from what entity or institution, and how these are administratively managed. The following graphs are good illustrations of a range that is used. Although there were interesting discrepancies in usage of certain sites between states, the notable names included: Newsela, Discovery Education, and the DBQ Project for paid resources. See Figures 23 and 24 below. (pp 90, 91).

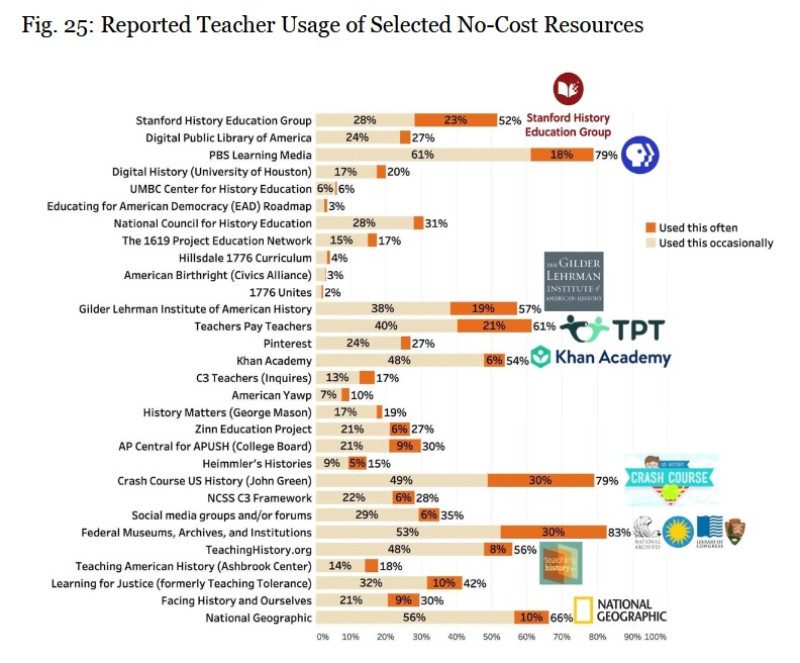

New American History including its various tools and Learning Resources is an example of the growing availability and use of Open Educational Resources (OER), which are freely accessible resources. A good percentage of surveyed teachers use such resources (59 percent) and an additional 45 percent use resources created by or recommended by other teachers.

A breakdown of some selected resources appears in Figure 25:

Researchers noted high degrees of trust in sources from federal institutions (e.g. the Library of Congress, Smithsonian). However, they also noted that the most frequently used sources outside of these are Crash Course History on YouTube, founded by John Green in 2013, and the Stanford History Education Group, established by Sam Wineburg (now called Digital Inquiry Group, or DIG). For further discussion of the resources mentioned in the surveys, including TeachersPayTeachers (TPT), see pages 92 to 95.

Explain:

Having discussed the sources used, what happens when we drill down into the classroom and look at the actual materials being used?

The next section of Part 3 covers the form of materials used to present the historical content they teach (the latter covered in Part 4). There is a breakdown of “expository” formats, which include things like textbooks to read or videos to watch, and “inquisitive” formats, which include document-based inquiry sources. Of note is the shift in the AHA itself’s perspective on textbooks vs document-based investigative learning. Hard to imagine but in 1899, they advised “‘limited contact with a limited body’ of primary sources”. (p 99) Eye-opening today, for sure! Further commentary on SHEG/DIG and the DBQ Project follows, showing different inquiry approaches the study found being used. Findings include a discussion of potentially good questions to ask vs others that might be considered “bad”. (p 102)

“Not all questions are created equal, however. Forced choices between moral absolutes, abstract queries of moral or civic concern, and overly fanciful counterfactuals abound. Stark and uncomplicated question constructions can too easily speed the inquiry process straight to argument, reducing history to a series of positions that one must take and defend.

Too many lessons ask students to stake a position on a moral binary, rendering judgment on a past policy or person from the perspective of a national (and present-tense) ‘we’.”

Teachers wanting to consider the kinds of inquiry exercises they use might want to read pages 102 to 105, “No Such Thing as a Bad Question?” or one of the two published pieces by the researchers, one in AHA Perspectives and one in The American Historical Review.

The final section in Part 3 examines “Vibes and Pressures,” or how politics and ideology shape teachers’ experiences today. While most teachers reported little or no objections to their teaching, the impetus of this report meant taking a look at when content choices get difficult. Sections that follow cover: Polarization and Pandemic; Pressures in Blue and Red; Mixed Settings and Pressures Outside the Spectrum; Defending History.

Discussion could include:

- What is an example of a “bad history question” you have seen in history materials? What’s an example of a “good” history question?

- Pre-service: Do you expect a lot of materials will be provided? Does your likely district (or state) have specific mandates that you are aware of?

- In-service: Have you experienced push back from students, parents or other community members around the content you teach? Have you changed the way you teach a topic because of external pressure from religious, political, or special interest groups?

Elaborate:

What about curricular content?

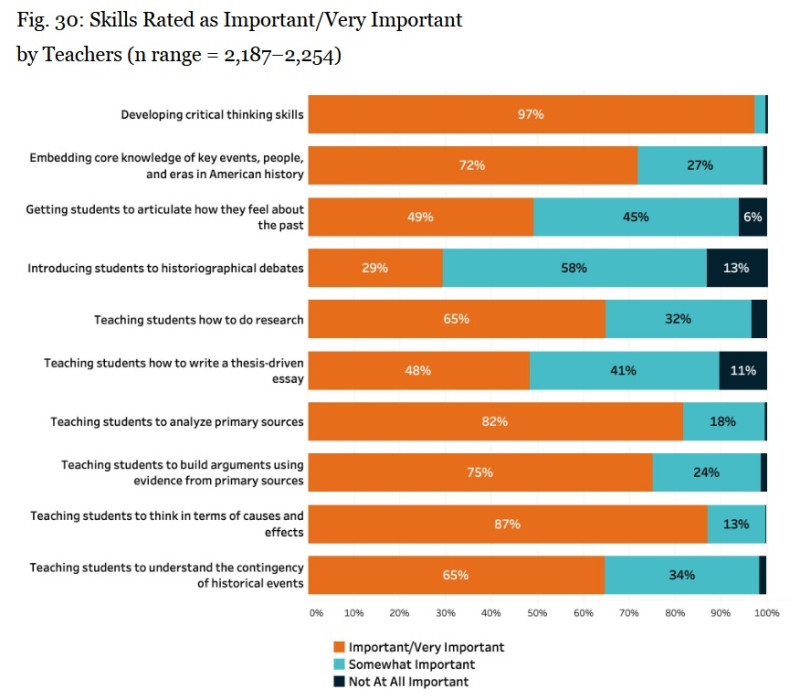

Part 4 of the report - “Curricular Content”, takes an in depth look at topics covered, yet it begins with an assessment of teachers’ “purposes, priorities, and favorites”. For example, on page 131 of the report there is a table showing the options teachers who were surveyed were able to choose from - on the one hand about what skills they felt were most important, and on the other what their goals and values are in the teaching of U.S. history.

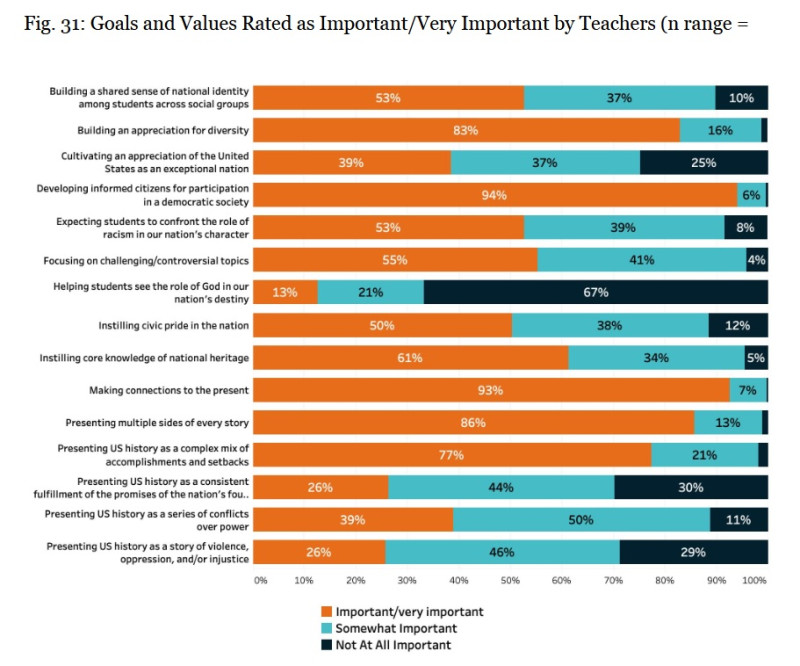

Findings appear in Figures 30 and 31, pages 132-133:

Unsurprisingly critical thinking skills are rated as highest in importance, with historiography showing up as the lowest priority for teachers. In terms of goals and values, the highest rated options were 'Developing informed citizens for participation in a democratic society’, followed closely by ‘Making connections to the present’. Worth noting here is that the researchers point out that responses showed “distinct cultural and political differences”, mainly distinct in geographical divisions. (p. 133)

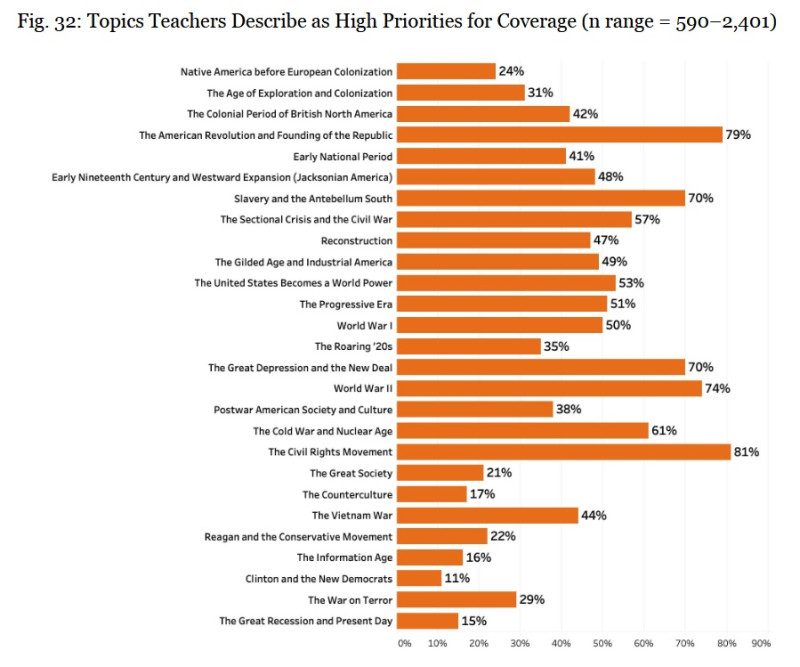

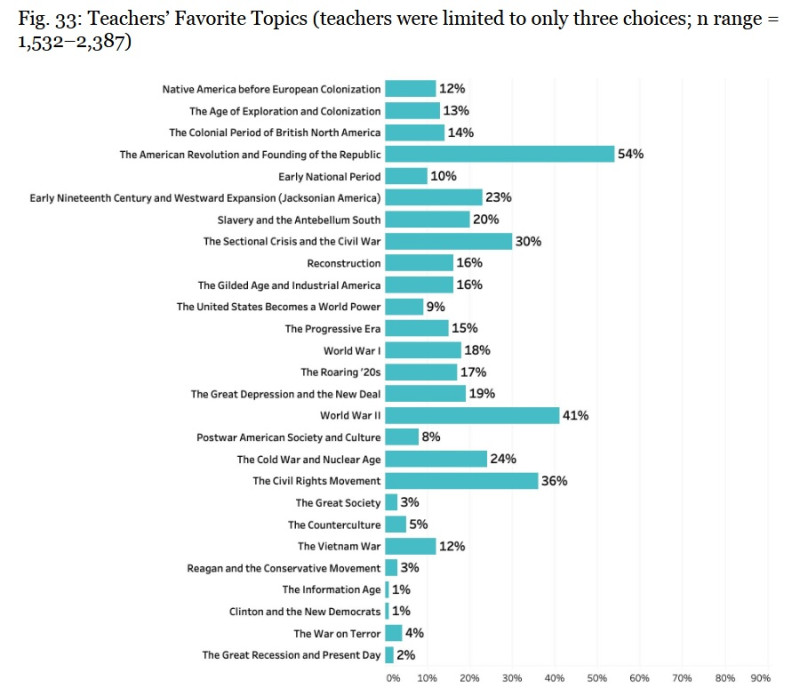

The next focus of the report is on topics covered. What were teachers’ chosen priorities, and what were their favorite topics to teach? The answers are visualized in the following two graphs. (Figures 32 and 33, pp. 135-136.)

As the text states: what you see in these responses “doesn’t square with ideological caricatures of politicized classrooms”. (p 136)

The remainder of Part 4 covers the “strengths, weaknesses, and patterns” found in the curricular materials researchers collected in six major U.S. history topics: Native American History; the

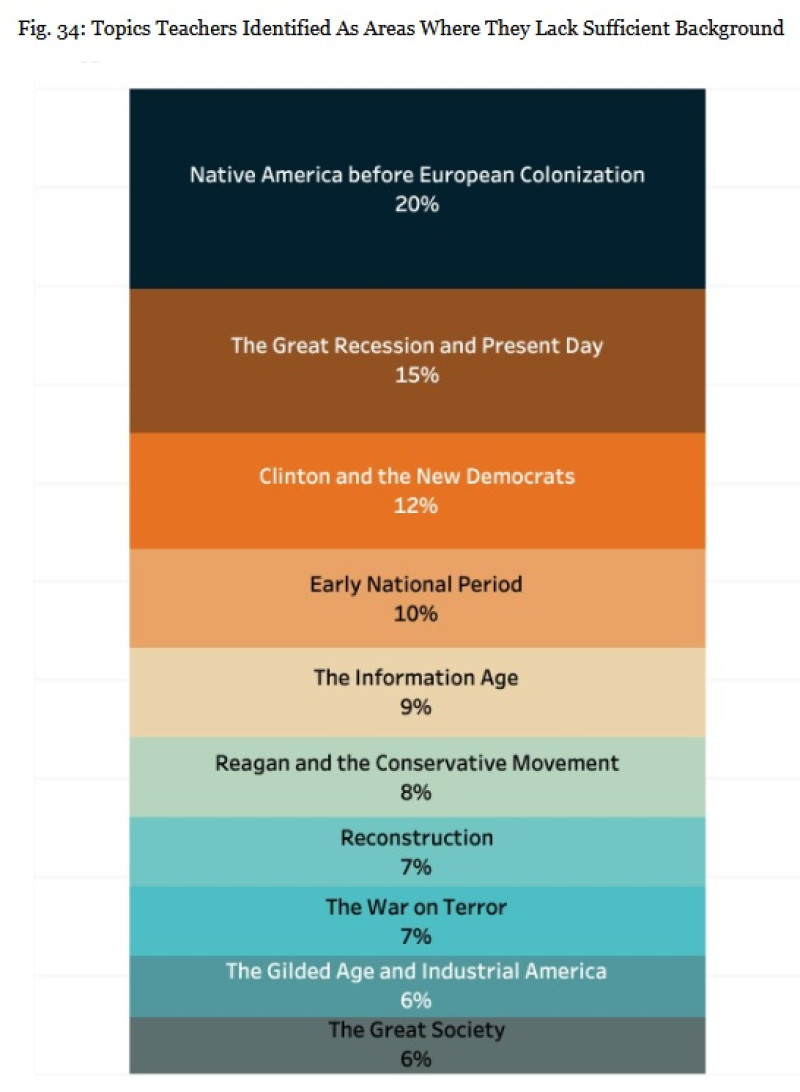

Founding Era; Westward Expansion; Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction; Industry, Capital, and Labor (also shown in places as the Gilded Age and Progressive Era); and the Civil Rights Movement. Interestingly they initially also asked teachers where they felt their own biggest weaknesses were, by topic. The results - which may surprise some - are shown here in Figure 34:

From this point forward, the report breaks down what was found when studying the materials being used by teachers in the six major topics chosen. For the first two - Native American History and the Founding Era - findings include graphs showing which states they checked had legislated any form of instruction on that topic in U.S. history. (In the latter case the term used was “Founding Documents”.) However, this was not included for the four following topics.

A detailed analysis of materials for each topic is published on pages 140 to 181. A few findings stand out for each topic:

Native American History - teachers feel weakest in content knowledge here. One difficulty with the topic is the spotty coverage of Native American history after the early nineteenth century

The Founding Era - numerous entities exist in the realm of knowledge production here, and that produces a wealth of material for teachers, perhaps greater than most other topics. This topic is also likely to garner controversy depending on how it is taught - broadly or with preconceived judgments. Additionally, the ongoing struggle to move beyond patriots and elites during the Revolutionary Era is quite notable. For example it is rare to find material on women, African Americans free and enslaved, Native Americans, and other non-white groups.

Westward Expansion - discusses the difficulty of the long used concept of “Manifest Destiny” and the fact that many secondary level teachers could benefit from updating their knowledge on how the topic is taught, while at the same time the use of state and local history for many states here is beneficial.

Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction - A popular topic, there is rarely now any serious controversy about the cause of the Civil War. That said, this also seems to be a good topic for breaking down preconceived ideas students might bring to the topic. Researchers also note that some of the most engaging material is often local. One of the more interesting findings is around the over-emphasis in some materials on military history.

Industry, Capital, and Labor (also called in places “The Gilded Age and Progressive Era”) - This topic is said to be the most “thematic”, though teaching the vastness of economic change in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is a big challenge. It seems to be a mixed bag how frequently the topic has been mandated, and it is often unevenly treated. It is the topic most likely to use a sociological approach.

The Civil Rights Movement - Researchers point out that this topic is very different if only by virtue of having numerous living participants and witnesses. It is also seen as a high priority topic. According to surveyed teachers it appears the lesson aligns with the Founding Era in terms of relating to civics and citizenship. The topic is, however, flagged by many teachers as a “flashpoint for controversy”. Local history can easily be embedded here, as can lessons on empathy.

In conclusion: instructional materials are very diverse across the states studied. Creativity in teaching turns up as a positive throughout the research.

The report’s conclusion restates some important findings, and these are encouraging. Of note:

“[Teachers] appear strongly committed to keeping their contemporary policy preferences from skewing how they teach. We heard repeatedly about the need for neutrality and balance. History teachers are committed to teaching students how to think, not what to think. They are committed to teaching both inspirational and hard histories and weighing multiple perspectives. These attitudes and commitments outline a politics of history education grounded in evidence as well as empathy, tolerance, and respect for the values and ideas of other people, past and present.”

For both pre-service and in-service teachers, the concluding thoughts on pages 184 to 186 are certainly worth reading. The researchers describe what is not included while stressing that it is hopeful, the report will impact teachers, administrators, and legislators alike. Again, as in the two videos (in both ‘Extend’ sections), there is emphasis on the need for better teacher training and professional development. They also propose that we should “restore, reinforce, and reinvest in teachers’ confidence as experts in their subject matter.” At New American History, we agree.

Discussion points:

- What topics in U.S. history do you feel most confident in teaching?

- What topics do you feel you need more background in to be an effective teacher?

- What support do you get that is most appreciated?

- What support do you need, but not get?

Extend:

Watch or listen to a Congressional Briefing about the AHA report.

The AHA has two posted videos you can watch to learn more from the researchers. One was a Zoom webinar + Q&A, and the other was a Congressional Briefing. Here we will give some highlights from the Briefing, which was held to introduce and share findings from the report. As the YouTube description states, the report “summarized key findings from the most comprehensive study of secondary US history education undertaken in the 21st century.”

The Briefing took place before the 2024 election, and viewers might note that in the introduction by Jim Grossman, AHA Executive Director, he states that controversy over teaching of U.S. history is “more heat than light”, or “political theater” with no evidence. It is doubtful that statement would have changed in light of the recent Executive Order (January 2025). Grossman also states that all Americans have “a stake in a citizenry that knows the nation’s history”. See also the AHA/OHA response to the January 2025 EO.

Opening the substantive part of the Briefing, Research Coordinator Nicholas Kryczka tells attendees that the U.S. education system is “diverse, devolved, and dynamic”. Kryczka then repeats the biggest “takeaways” he sees from the report, revising those given in the earlier webinar:

- Apathy not activism is the biggest problem;

- Teachers retain substantial discretion on curriculum;

- In spite of localized structures, most teaching is on common ground, for example, the shift in materials used, e.g. the disappearing textbook & rise of online resources;

- The focus on inquiry has negative effects in addition to the positive, these are often overlooked;

- Teachers both desire and deserve more professional development.

The second presentation was from Brenda Santos, an education researcher at Brown University. Santos calls the report “rich” with findings. She also notes that “US History classrooms don't look like the caricatures of History instruction held up by critics on both ends of the political spectrum”. At the same time, she noted, the report “did identify a persistent and concerning under-resourcing of history teachers”. Santos stated that under-resourcing takes three main forms: “insufficient curricular materials, inadequate professional development, and limited attention or respect for history within the instructional program”.

The third speaker was Jonathan Zimmerman of the University of Pennsylvania, a professor specializing in education policy and history. His remarks include his reactions to the report. One surprise he found was that there is amazing uniformity in history teaching, despite there being no national “system” for history education. Zimmerman also notes - in agreement with Kryczka and Santos - that history teachers need both more time and more assistance, especially with content.

From 42:00 viewers might watch the Q&A portion of the Briefing. This includes Grossman asking the panel what surprised them most in the report. Grossman also mentions policy priorities, “which we don’t usually do”. He notes that all three panelists would agree that a priority the Briefing attendees should take back to their offices involves “high-quality PD [professional development] funding”. Another general consensus is that history teachers should have a deeper background in the history discipline itself.

Further comments include Santos stating that the pacing is so quick that teachers have to push through content too quickly and that pressure means students do not get quality instruction in history. While comments on online resources were critical in part, it is noted that there can be great resources for the use of data in history and that is encouraging. They also note that the inclusion of state and local history, and leveraging local connections, is a very good thing.

Webinar discussion points might look like:

- Did you learn more from watching the Briefing beyond simply reading the text of the Learning Resource?

- What further questions might you want to pose to the panelists, rather than the researchers who put together the report?

- If you could be sure the Briefing included one or two topics of concern that you would like your congressperson(s) to hear, what might they be?

Citations:

American Historical Association, American Lesson Plan: Teaching US History in Secondary Schools (Washington, DC: American Historical Association, 2024).

Mapping the Landscape of Secondary US History Education team:

Research Coordinator: Nicholas Kryczka; Researchers: Whitney E. Barringer, Lauren Brand, Scot McFarlane; Project Directors: Brendan Gillis (2023–24); Alexandra F. Levy (2022–23); Sarah Jones Weicksel (2022).

Whitney E Barringer, Scot McFarlane, Nicholas Kryczka, Good Question: Right-Sizing Inquiry with History Teachers, The American Historical Review, Volume 129, Issue 3, September 2024, Pages 1116–1127, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhae290

Whitney E. Barringer, Lauren Brand, Nicholas Kryczka. No Such Thing as a Bad Question? AHA Perspectives on History, September 26, 2023. https://www.historians.org/perspectives-article/no-such-thing-as-a-bad-question-inquiry-based-learning-in-the-history-classroom-september-2023/

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc.