This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Why History Matters

View Student Version

Standards

C3 Framework:D3.1.9-12. Gather relevant information from multiple sources representing a wide range of views while using the origin, authority, structure, context, and corroborative value of the sources to guide the selection..

National Council for Social Studies:Theme 2 - TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGETheme 5 - INDIVIDUALS, GROUPS, AND INSTITUTIONS

National Geography Standards: Standard 17 - How to apply geography to interpret the pastStandard 18 - How to apply geography to interpret the present and plan for the future.

College Board AP U.S. History (Fall 2020):HISTORICAL THINKING SKILLS COVERED:SKILL 4.A – Identify and describe a historical context for a specific historical process or development.SKILL 5.A: Identify patterns or connections between historical developments.

EAD FrameworkTheme: Civic Participation Design Challenge: Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

Suggested Grade Levels: High School (9-12), especially Advanced Placement U.S. History course

Suggested Timeframe: One or two 90-minute class periods

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet or mobile device, projection screen

Key Vocabulary

Evidence - in historical terms, something you see, experience, or read that acts as a record of the past

Historical method - the frameworks and techniques that historians use to create accounts of the past; it involves interpretation of source evidence and a thorough fact-checking process

Historiography - a study of the methods historians use to create historical narratives

Interpret - to explain the meaning of information

Narrative - a spoken or written account of the past

Perspective - in historical terms, the point of view of a source, which can give a historian a fuller backstory of the person or event being studied

Philosophies of history - schools of thought that a group of historians have, which involve interpreting the past through a certain lens or framework

Whig History School of Thought - an interpretation of history in which humanity is continuously becoming freer and more enlightened with time

Read for Understanding

Teacher tips

New American History Learning Resources may be adapted to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in partners or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs and Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge.

In addition, this Learning Resource uses Turn and Talk to allow students to work with an “elbow partner” for brief collaborations. In addition, this Learning Resource uses “Thinking Routines” from Project Zero, a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education that has developed learning strategies that encourage students to add complexity to their thought processes. For an overview of Project Zero’s methodology, you may want to read its Exploring Complexity Bundle. Specifically for this lesson, students will use these thinking routines: Creative Question Starts, Take Note, See, Think, Wonder, I Used To Think… Now I Think.

These Learning Resources follow a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience, or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

For Students:

In this Learning Resource, you will examine Why History Matters. You will also learn about Historiography and about a variety of schools of thought around historical interpretation.

Engage:

What is the purpose of studying history?

Can’t we just look up historical facts online? Can’t we outsource the memorization of names and dates to the Internet? The study of history is much richer and more important than learning a list of facts to pass a test.

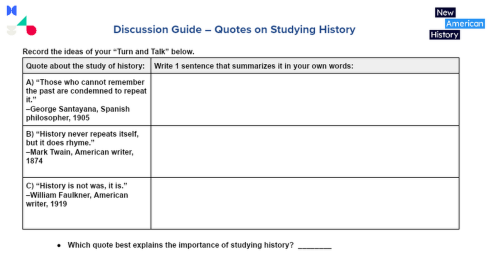

Read the following three quotes. (Your teacher might project them on the board.) Use the Turn and Talk strategy with a partner. First, summarize in your own words what each quote means. Then, discuss which of the three quotes you think best explains why the study of history is important. Lastly, after you have talked, complete this Discussion Guide.

A) “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

B) “History never repeats itself, but it does rhyme.”

C) History is not was, it is.”

Lastly, present your ideas to the whole class. Your teacher will lead a discussion on these ideas. If working remotely, you may use breakout rooms through videoconferencing, or share via a collaborative document such as Google Docs or Google Slides.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

Why is history important?

The study of history is a study of stories. By seeing how people and groups met challenges, by learning how they succeeded and what limited their success, we gain empathy. In a way, the study of history can provide a blueprint for who we are and who we’re not.

View “Why is History Important,” as Dr. Julian Hayter, a historian at the University of Richmond, explains his perspective on why history is important to study.

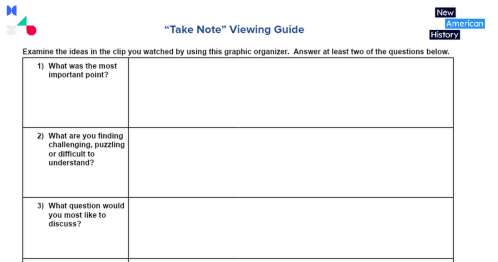

After you watch, answer at least two of the questions below on your Viewing Guide, which uses the “Take Note” Thinking Routine:

- What is the most important point?

- What are you finding challenging, puzzling or difficult to understand?

- What question would you most like to discuss?

- What is something you found interesting?

To share your response, your teacher may provide access to a Google Docs discussion board, or allow you to collaborate on a Google Slides set. Your teacher will debrief by reviewing the main ideas of each piece and by reading back student responses to the class and asking follow-up questions or by asking you to turn and talk to a partner to share your answers

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

What does a historian do?

People need to make sense of the past in terms that they – living in the present – can understand. And that’s the work of the historian: to interpret past events and stitch together a meaningful narrative.

In this section, you will learn about historiography: what it is and why it’s different from learning a set of facts. First, analyze this quote:

“Each age tries to form its own conception of the past. Each age writes the history of the past anew with reference to the conditions uppermost in its own time.”

To what extent do you agree with it? Use the “Think, Pair, Share” Thinking Routine to examine the quote and to form an argument about it.

Your teacher will then lead a whole-class discussion, in which students share ideas discussed in their partner groups.

Next, view this segment of “Historiography,” in which Dr. Julian Hayter, a historian at the University of Richmond, explains historiography in greater detail.

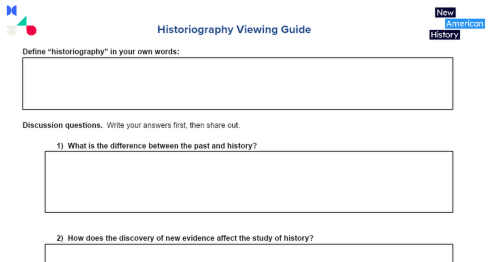

After you view, complete the Historiography Viewing Guide. Define historiography in your own words and then answer these questions:

- What is the difference between the past and history?

- How does the discovery of new evidence affect the study of history?

To share your response, your teacher may provide access to a Google Docs discussion board, or allow you to collaborate on a Google Slides set.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

What are the philosophies used to interpret the past?

Historians can be organized into different philosophical groups that highlight the different ways that they’ve examined the forces that have shaped the past. These schools of thought emphasize different historical themes and view the past through different lenses. They all hold value.

View another segment of "Historiography," narrated by Dr. Julian Hayter, a historian at the University of Richmond.

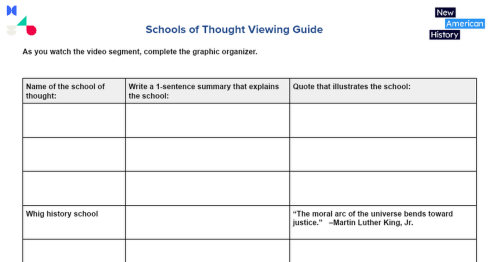

In this segment, Dr. Hayter explains six historical schools of thought. Identify and summarize each one using the Schools of Thought Viewing Guide.

Next, identify the school that fits your thinking the most, as well as the school that fits you the least. Build arguments to explain your decisions. Lastly, for at least two of the schools, do Web research to find a quote that illustrates the meaning of the school’s philosophy. For example, within the Whig History School of Thought, this Martin Luther King, Jr. quote illustrates the view that humanity is becoming freer and more enlightened with time:

“The moral arc of the universe bends toward justice.”

To share your responses with the whole class, your teacher may provide access to a Google Docs discussion board, or allow you to collaborate on a Google Slides set.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

Why do historical research methods matter?

History follows a set of rules; it is not simply a record of everything that has happened. The stories that historians piece together are made up of sources and evidence that must be rigorously checked and verified for their credibility. The historical method is a technique that considers ethics and seeks to weed out myth-making and propaganda-pushing.

View “Historial Method,” narrated by Dr. Julian Hayter, a historian at the University of Richmond.

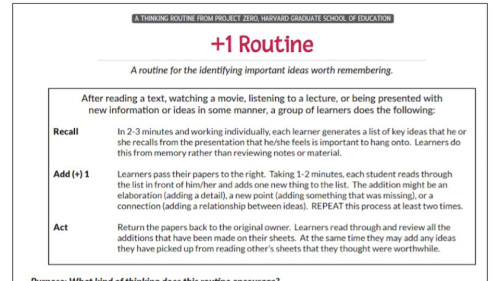

After you finish viewing, complete the “+1 Routine” Thinking Routine.” In three minutes, make a list of key ideas that grabbed your attention on a blank sheet of paper. Then, pass your paper one student to the right. Read the list. Take two minutes to expand on an idea, make a new point, or make a connection to another topic. Repeat this process at least two more times. Return the paper to its original owner.

Your teacher will then lead a whole-class discussion, in which students share ideas added to their papers.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

“Historical Method” New American History, University of Richmond, 2022. https://youtu.be/epO2yX4oIgs.

“Historiography” New American History, University of Richmond, 2022. https://youtu.be/avguQ13ZdG4.

“Project Zero's Thinking Routine Toolbox.” PZ's Thinking Routines Toolbox | Project Zero. Accessed July 6, 2022. https://pz.harvard.edu/thinking-routines.

“Turn and Talk.” the. Accessed July 6, 2023. https://www.theteachertoolkit.com/index.php/tool/turn-and-talk.

“Why is History Important?” New American History, University of Richmond, 2022. https://youtu.be/A-6VZR5scgU.

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc