This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

The Wilkes Expedition

View Student Version

Standards

C3 Framework:D2.His.3.6-8.D2.His.3.9-12.

National Council for Social Studies:Theme 2 - TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGETheme 5 - INDIVIDUALS, GROUPS, AND INSTITUTIONS

National Geography Standards: Standard 17: How to apply geography to interpret the past

College Board AP U.S. History (Fall 2020)HISTORICAL THINKING SKILLS COVERED: SKILL 4.A – Identify and describe a historical context for a specific historical process or development.SKILL 5.A: Identify patterns or connections between historical developments.TOPIC 1.3:THEME 6: AMERICA IN THE WORLD (WOR) This theme focuses on the interactions between nations that affected North American history in the colonial period and on the influence of the United States on world affairsUNIT 1: LEARNING OBJECTIVE C. Explain the causes of exploration and conquest of the New World by various European nations.KC-1.2.I.A: European nations’ efforts to explore and conquer the New World stemmed from a search for new sources of wealth, economic and military competition, and a desire to spread ChristianityTOPIC 1.6:THEME 6: AMERICA IN THE WORLD (WOR) This theme focuses on the interactions between nations that affected North American history in the colonial period and on the influence of the United States on world affairsUNIT 1: LEARNING OBJECTIVE F. Explain how and why European and Native American perspectives of others developed and changed in the period.KC-1.2.III - In their interactions, Europeans and Native Americans asserted divergent worldviews regarding issues such as religion, gender roles, family, land use, and power.

EAD Roadmap Connections: Theme: We the People Cultivate understanding of personal values, principles, commitments, and community responsibilities. Explore the challenges and opportunities of pluralism, diversity, and unity within the U.S. and abroad. Analyze the impact of enslavement, Indigenous removal, immigration, and other hard histories on definitions of and pathways to citizenship. Evaluate the extent to which marginalized groups have won incorporation into “the people” and advanced the shared values and principles of the U.S.

Teacher Tip: Think about what students should be able to KNOW, UNDERSTAND and DO at the conclusion of this learning experience. A brief exit pass or other formative assessment may be used to assess student understandings. Setting specific learning targets for the appropriate grade level and content area will increase student success.

Suggested Grade Levels: High School (9-12), AP U.S. History

Suggested Timeframe: Two 90-minute classes, or four 45-minute sessions

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet or mobile device

Key Vocabulary

Antebellum - the time period before a particular war (from the Latin ante ‘before’ and bellum ‘war’), especially used to refer to the time before the American Civil War

Archipelago - a group of islands

Botanist - an expert in, or student of, the scientific study of plants

Compass - a navigational instrument which indicates the direction of magnetic north

Conchologist - a person who studies conchology, the branch of zoology that deals with shells, particularly those of mollusks

Contours - lines on a map that indicate changes in elevation; (in figurative usage) the general outline or shape of an idea or event

Cultivation - the action of preparing and using land for crops or gardening

Draftsman - a person who makes detailed technical plans or drawings (also, draughtsman, and draftsperson)

Excerpt - a short section of a longer text

Horticulturalist - an expert in or student of garden cultivation and management

Marine chronometer - a precise clock used for maritime navigation

Mineralogist - a scientist who specializes in the study of minerals, focusing on their chemistry, crystal structure, and physical properties, including their formation, distribution, and occurrence

Myriad - a countless or extremely great number

Narrative - a spoken or written account of connected events

Naturalist - an expert in or student of natural history; synonyms: natural historian, life scientist, wildlife expert

Philologist - a specialist in the study of language and literature, focusing on their history, structure, and use, often with an emphasis on cultural and historical context

Strait - a narrow channel of water connecting two larger bodies of water

Sextant - a navigational instrument used to determine the angle between the horizon and a celestial body like a particular star, planet, or moon

Read for Understanding

Teacher Tips

New American History Learning Resources may be adapted to a variety of educational settings, including remote learning environments, face-to-face instruction, and blended learning.

If you are teaching remotely, consider using videoconferencing to provide opportunities for students to work in partners or small groups. Digital tools such as Google Docs or Google Slides may also be used for collaboration. Rewordify helps make a complex text more accessible for those reading at a lower Lexile level while still providing a greater depth of knowledge.

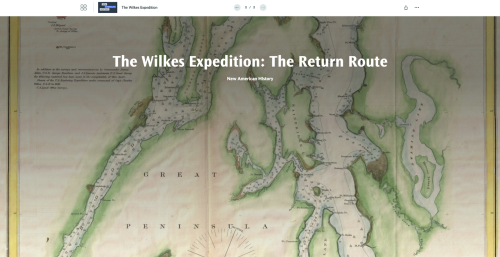

This Learning Resource utilizes a StoryMap about the Wilkes Expedition made by New American History. The StoryMap is divided into two parts, 1 and 2. Part 1 focuses on the outbound expedition in three sections ("The Crew, The Discoveries, The Initial Route"). Part 2 focuses on “The Return Route” and includes an “Atlas of Charts”. Also included are the expedition’s published records, Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. The five-volume set is a large document and will load very slowly.

This Learning Resource uses primary source analysis and graphic organizers, and most of the work has students working in pairs and/or small groups.. This Learning Resource also uses materials from Bunk, a shared home for the web's most interesting thinking about American history. It also uses materials in the public domain from the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress. This Learning Resource also uses Turn and Talk to allow students to work with an “elbow partner” for brief collaborations.

These Learning Resources follow a variation of the 5Es instructional model, and each section may be taught as a separate learning experience, or as part of a sequence of learning experiences. We provide each of our Learning Resources in multiple formats, including web-based and as an editable Google Doc for educators to teach and adapt selected learning experiences as they best suit the needs of your students and local curriculum. You may also wish to embed or remix them into a playlist for students working remotely or independently.

Read for Understanding (Students)

The United States Exploring Expedition—often known simply as the “Ex Ex” or the “Wilkes Expedition”—was a U.S. government-sponsored project to survey and explore the Pacific Ocean and its islands in the mid-19th century. Along their voyage, the explorers not only produced maps, but collected all kinds of data and specimens relating to both the natural and human histories of the Pacific. Much of this material served as the basis for the beginning of the Smithsonian Institution, which today is the world's largest museum and research complex with over 157 million objects and specimens. Part 1 focuses on the outbound expedition in three sections ("The Crew, The Discoveries, The Initial Route"). Part 2 focuses on “The Return Route” and includes an “Atlas of Charts”.

Engage:

What were the contours of the “Ex Ex” journey?

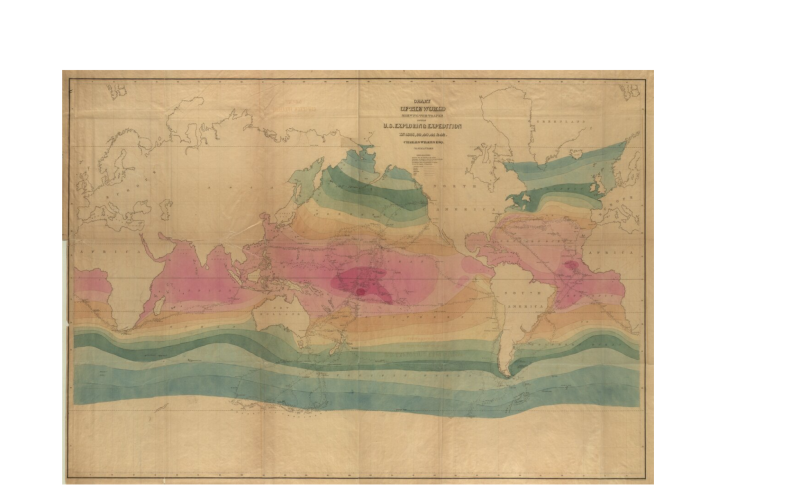

The United States Exploring Expedition—often known simply as the “Ex Ex” or the “Wilkes Expedition”—was a U.S. government-sponsored project to survey and explore the Pacific Ocean and its islands in the mid-19th century. At that time, as the country was expanding westward, leaders realized that American maritime exploration was lagging behind the efforts of Britain and France. Led by U.S. Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes almost 350 men across six sailing ships departed Hampton Roads, Virginia on August 18, 1838, and set off on a sprawling, four-year-long journey. They stopped in Brazil, Peru, Samoa, Sydney, San Francisco, Puget Sound, the Philippines, and, perhaps most significantly, Antarctica. These were just some of their numerous destinations. While Wilkes was not the first to encounter the great, icy southern continent we now call Antarctica, he and his men mapped 1,500 miles of its coastline, significantly advancing understanding of its size and shape at the time. Along their voyage, the explorers not only produced maps but collected all kinds of data and specimens relating to both the natural and human histories of the Pacific. Much of this material served as the basis for the beginning of the Smithsonian Institution.

To start your investigation of the Exploring Expedition, you will look briefly at the American Visions StoryMap. This will give you a broad overview of the Ex Ex before you dive into primary source materials. With a partner, scroll through the StoryMap, paying attention to who is on the expedition, where the expedition goes, why they chose to explore, and how they navigated unfamiliar parts of the globe.

Here is the opening page of the StoryMap. Open the link above and scroll down to explore.

Make sure to pay attention to the various professions of the members of the expedition.

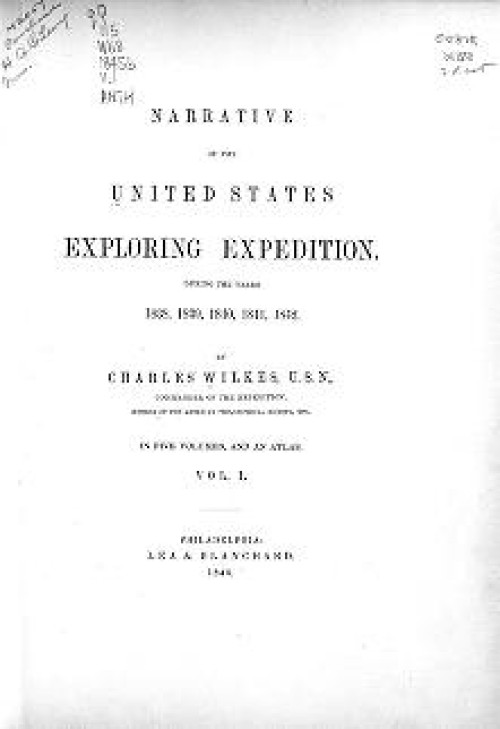

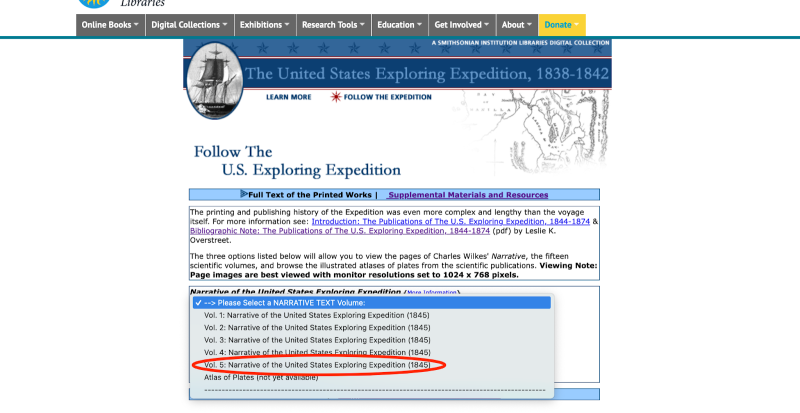

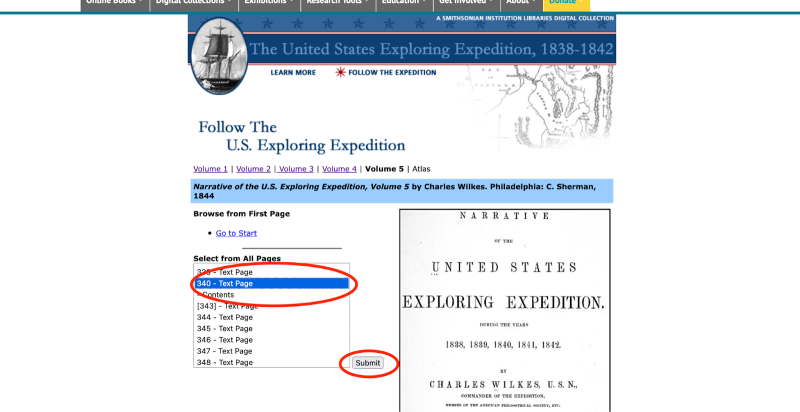

Next, explore the table of contents of the expedition’s published records, Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. The five-volume Narrative was written by the expedition commander, Charles Wilkes, and published in 1844. (Note that it is a large document and will load very slowly.)

Your teacher will split you into five groups, and each group will examine the table of contents of one of the volumes of the Narrative. Select Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4, or Vol. 5 as assigned by your teacher. Then select “Contents” on the left. You may have to click through several pages of the table of contents.

As you read the Table of Contents, try to use the subject headings to understand the overall objectives and findings of the expedition.

- Is there anything that sticks out to you?

- Is there anything unexpected?

After you take fifteen minutes to examine and discuss the Table of Contents of your volume, each group will share their general impressions with the class.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explore:

What was the mandate of the Ex Ex?

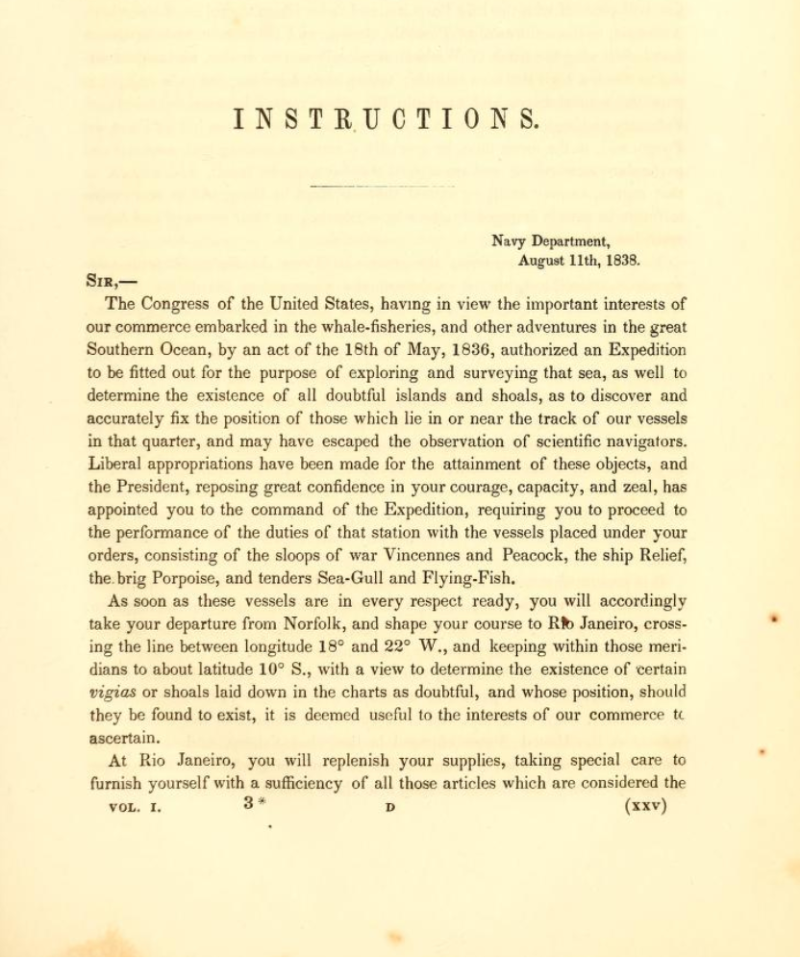

On August 11, 1838, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy, J.K. Paulding, sent instructions to Charles Wilkes outlining the goals and expectations for the U.S. Exploring Expedition. Wilkes published these instructions at the front of the first volume of the narratives of the expedition.

Read and make a copy of the linked document so you can annotate your own copy of an excerpted version of those instructions. As you read think about the following questions, highlighting or underlining any passages that interest you:

- What are the U.S. government’s hopes for the expedition?

- What is its “primary object”?

- What is the exhibition not meant to be?

- How is the ocean, and the natural world more generally, portrayed?

- How are people portrayed?

- How does the Navy think about the collection of scientific information?

- What is the perceived role of this information in the project of nation-building?

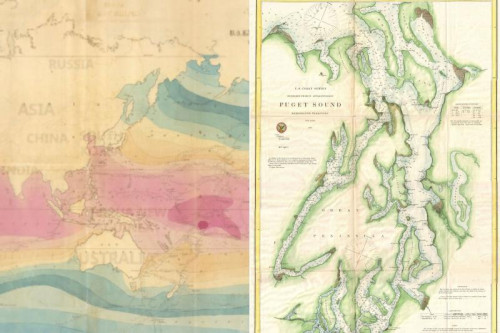

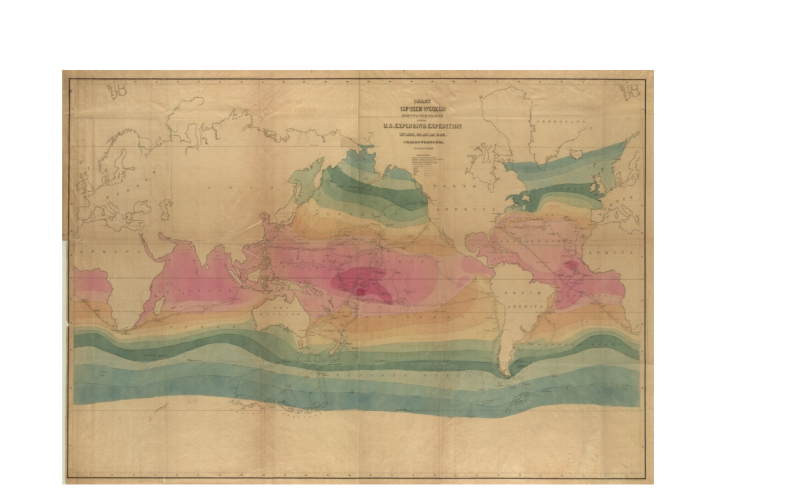

Your teacher will display this map of the Exploration Expedition’s path or allow you to access it digitally on your school device. As a class, work collaboratively to trace the route of the expedition. It might be tricky to follow the exact path of the six different ships, but do the best you can. Then, your teacher will provide time for a whole class discussion (or allow you to work in small groups) to share any other observations you have about the map. Discussion points might include:

- What does it emphasize?

- What does it minimize?

- Who decides what narratives a map does/does not tell?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Explain:

How did the crew represent forms of knowledge needed for the success of the Ex Ex?

The Exploring Expedition crew included nine different artists and scientists to study and record any number of things the explorers might encounter throughout their journey. On board the expedition was a philologist (someone who studies the history of language), a conchologist (someone who studies shells), a mineralogist (someone who studies minerals in rocks), a botanist (someone who studies plants), a horticulturalist (someone who also studies plants, principally in regards to cultivation), a draftsman (someone to make illustrations), and two naturalists (someone who broadly studies organisms in their natural environment).

You can learn more about these various jobs in part 1 (“The Crew”) of the StoryMap. If you are curious about how these jobs relate to modern-day careers, you can click the green button at the bottom left of each profile.

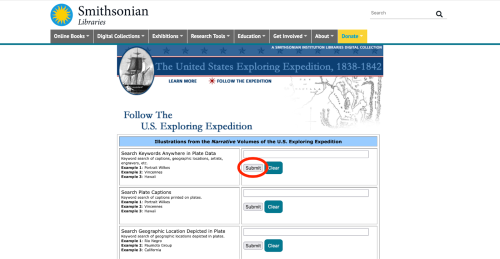

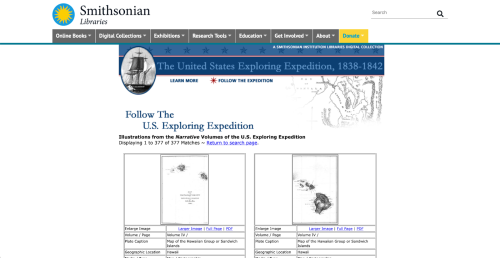

In pairs, or as directed by your teacher, analyze how each of these experts observed the world throughout the expedition. Investigate the different forms of information recorded by the explorers, and how this information together painted a picture of the myriad places the explorers visited. Use the digitized records from the Exploring Expedition available through the Smithsonian Libraries as linked in the StoryMaps. Follow the steps below:

- Begin by selecting the following links to access the databases for narrative records and scientific records from the expedition.

- On the landing page for both narrative and scientific records, there are four search boxes. In the first search box, titled “Search Keywords Anywhere in Plate Data,” click the “Submit” button without typing anything into the search box itself. This will allow you to see all the available illustrations at once.

Working individually or with a partner, as directed by your teacher, take several minutes to scroll through the illustrations and observe. You can start with either scientific or narrative records, but make sure you look at both.

- What are the similarities between the two?

- What are the differences?

- What kind of data is being collected?

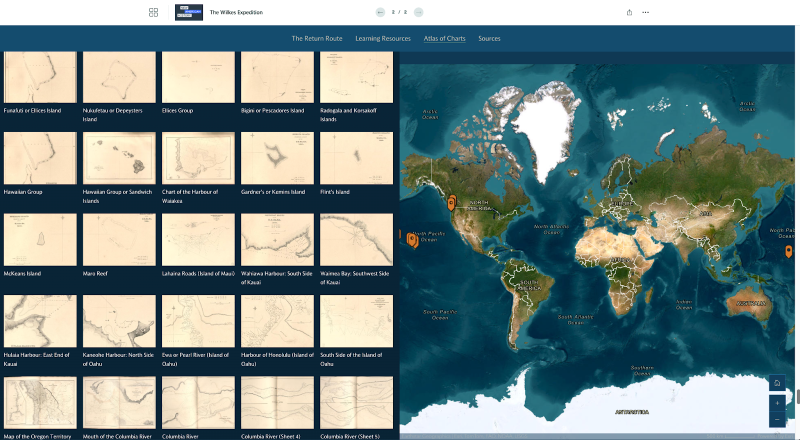

- Once you both feel that you have an understanding of the various types of records that the explorers created, pick a specific geographic location to investigate. (For more information about where the expedition went, you can also consult the “Atlas of Charts” section at the end of the StoryMap.)

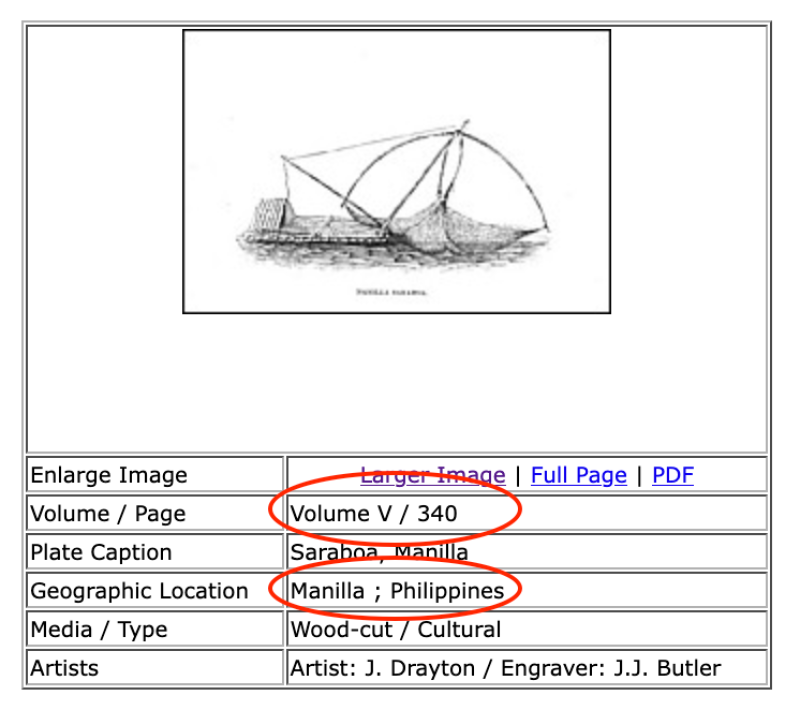

- Choose two illustrations from the narrative records and two from the scientific records that are from the same location (e.g., Fiji, Rio de Janeiro, Antarctica). Some records don’t have a location attached to them (especially the scientific ones), and some are extremely broad, like “Pacific”—try to avoid these. Try to choose a diverse set of records—not just landscape drawings or maps or shell drawings, for example, but a mix.

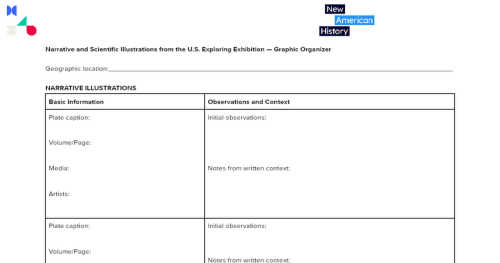

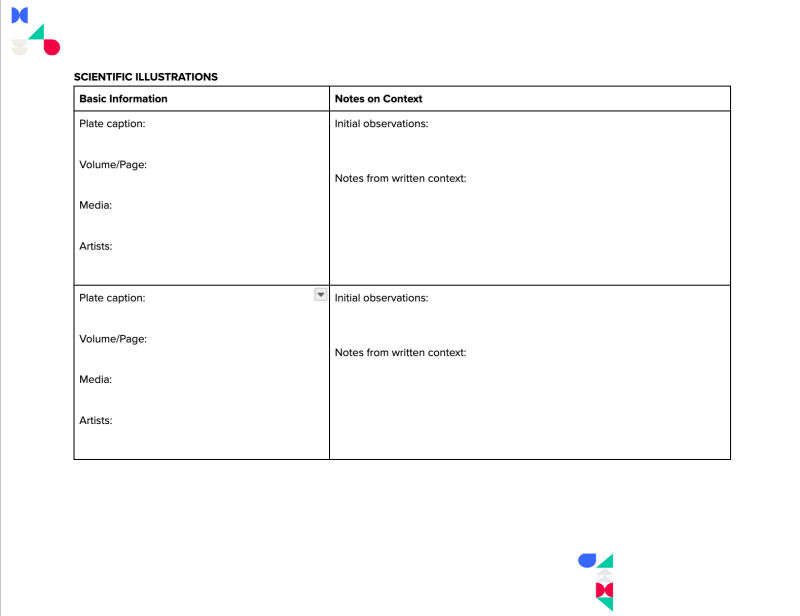

- Make a copy of this graphic organizer and record the basic information about the four illustrations. (Your teacher may provide a paper copy as needed.)

- Now, take several minutes to examine the specific records you have chosen more closely. Turn and Talk to your partner or nearest classmate about what you notice. Think about how humans and cultures are depicted. Think about how the natural world is depicted. Then, summarize your observations in the graphic organizer.

- To gather more context about what each image might be depicting, you can read the text accompanying the illustration. To see where the illustration was taken from, you can look at the “Volume/Page” data beneath the thumbnail image. Then, find the corresponding volume and page here. You may have to search several pages forward or backward to find the context for the image. Then, summarize what you learned in the graphic organizer.

Think about the story that these four objects tell about the geographic location of your choosing. Also think about how the information collected fits into the mandate given by Secretary Paulding.

- Does it ever go against this mandate?

- What other observations might you have included if you had helped write the report?

In pairs with a partner or in a small group, as directed by your teacher, take turns sharing what you learned from each illustration, and try to tell a story about your chosen location based on what you learned.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Elaborate:

How did the Ex Ex explorers bring the Pacific home?

Independently, or with a partner, look briefly at part 2 of the StoryMap to learn about the expedition’s return.

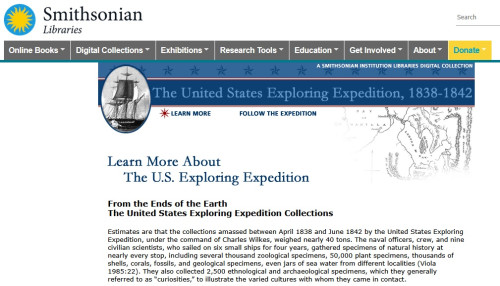

When the expedition returned home the explorers’ illustrated observations, along with the huge number of objects they collected, were put on display in the Great Hall of the U.S. Patent Office. Several years later these objects were transferred to the Smithsonian Institution, eventually becoming a key aspect of the collections of the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, D.C. Today, the Smithsonian is the world's largest museum and research complex with over 157 million objects and specimens.

Read “From the Ends of the Earth: The United States Exploring Expedition Collections” - the story of the collections as told in 2004 by Smithsonian anthropologist, Jane Walsh.

In small groups, discuss the following:

- How did specimens from the expedition physically make their way back to the United States?

- What roadblocks did museum administrators and collections specialists face in assembling and cataloging the material from the expedition?

- How did the Exploration Expedition shape the NMNH as an institution?

- How did the explorers’ observations shape American perceptions of various Pacific cultures?

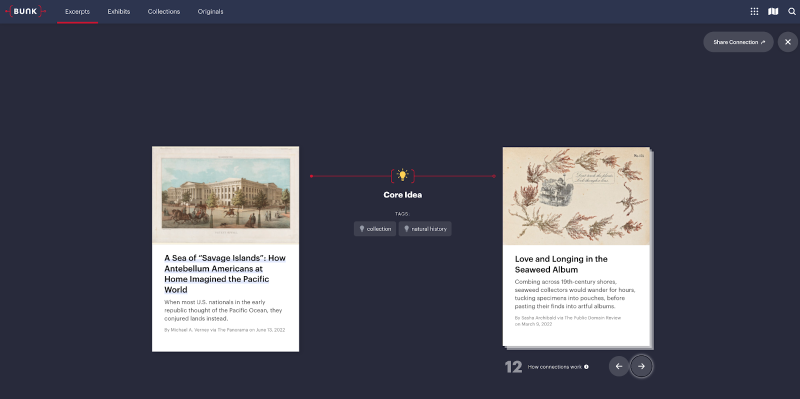

Next, read “A Sea of ‘Savage Islands’: How Antebellum Americans at Home Imagined the Pacific World” a Bunk excerpt by Michael A. Verney from The Panorama. Verney is a professor of early American history whose research focuses on American influence abroad. His 2022 book A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (University of Chicago Press) discusses the Exploring Expedition at length.

Explore some of the Bunk Connections to the excerpt to see how they relate to what you read.

After reading the excerpt and exploring the Bunk Connections, revisit the third and fourth questions from the bulleted list above.

- How did the Exploration Expedition shape the NMNH as an institution?

- How did the explorers’ observations shape American perceptions of various Pacific cultures?

Lastly:

- Did Verney’s article change or enhance your perception of the collections?

- Provide one example from another Bunk Connection that led you to your new thinking on the topic.

Write a short reflective journal entry, or use SketchNotes to reflect on what you believe to be a museum’s responsibility in exhibiting cultural artifacts.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Extend:

What is the role of Antarctica in building global influence?

Begin by reading “The Forgotten American Explorer Who Discovered Huge Parts of Antarctica”, a Bunk excerpt by Gillian D’Arcy Wood originally published in Smithsonian Magazine. You will already be familiar with some of the information in this article, but focus particularly on the second half of the piece, which outlines the history and present importance of “Antarctic affairs.”

Next, read section B, “History of U.S. Involvement in the Antarctic” from the 1996 National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Report on the U.S. Antarctic Program, Committee on Fundamental Science, National Science and Technology Council.

In small groups, discuss the following:

- How has Antarctica been perceived by the United States throughout history? What has remained the same? What has changed?

- Why might the United States., or any country, be interested in influencing Antarctica?

- What does Wood’s article demonstrate about contemporary politics and global competition between the U.S. and China (you can optionally read more about this here and here)?

- Lastly, consider that the original Exploration Expedition was meant to “extend the empire of commerce and science”. What do you think about that goal in the context of Antarctica today?

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Citations:

Darcy Wood, Gillen. “The Forgotten American Explorer Who Discovered Huge Parts of Antarctica.” Smithsonian Magazine, March 26, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/charles-wilkes-antarctica-explorer-180974432/.

Smithsonian Libraries, “Follow the U.S. Exploring Expedition”, 2004. https://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/usexex/follow.htm

United States Antarctic Program. Committee on Fundamental Science, National Science and Technology Council, April 1996. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/1996/nstc96rp/.

Verney, Michael A. “A Sea of ‘Savage Islands’: How Antebellum Americans at Home Imagined the Pacific World.” The Panorama, June 13, 2022. https://thepanorama.shear.org/2022/06/13/a-sea-of-savage-islands-how-antebellum-americans-at-home-imagined-the-pacific-world/

Wilkes, Charles. Narrative of the U.S. Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. 5 vols. Philadelphia: C. Sherman, 1844.

Wilkes, Charles. Chart of the world shewing the tracks of the U.S. Exploring Expedition: in 1838, 39, 40, 41 & 42. 1842. Map. Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Rare Map Collection, https://dlg.usg.edu/record/guan_hmap_hmap1842w5?canvas=0&x=4922&y=983&w=6749.

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc