This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Unpacking the AHA Report: American Lesson Plan, Part 1

Standards

Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP)

Standard 1: Content and Pedagogical Knowledge Moving on to other resources, there is an understandable focus on what digital or online sources are used, from what entity or institution, and how these are administratively managed. The following graphs are good illustrations of a range that is used. Although there were interesting discrepancies in usage of certain sites between states, the notable names included: Newsela, Discovery Education, and the DBQ Project for paid resources. See Figures 23 and 24 below. (pp 90, 91).

The provider ensures that candidates develop an understanding of the critical concepts and principles of their discipline and facilitates candidates’ reflection of their personal biases to increase their understanding and practice of equity, diversity, and inclusion. The provider is intentional in the development of their curriculum and clinical experiences for candidates to demonstrate their ability to effectively work with diverse P-12 students and their families.

Educating for American Democracy (EAD) Roadmap:

https://www.educatingforamericandemocracy.org/the-roadmap/

“Supporting deeper history and civic learning for young people has never been more important, and to do that, educators themselves need access to effective professional learning experiences that help them deepen subject matter and instructional expertise and navigate the challenges and tensions of teaching in a complex climate.”

Suggested Audience: In-service and pre-service educators

Suggested Timeframe: Could be divided over 3-5 Professional Learning Community (PLC)/planning periods or individual class sessions in an Edu course for pre-service educators.

Suggested Materials: Internet access via laptop, tablet or mobile device

Key Vocabulary

Anecdotal - evidence consisting of personal accounts or observations, as opposed to evidence built from research and analysis of large data sets.

Antecedents - predecessors; a thing or event that existed before or logically precedes another.

Assessment - the ongoing process of gathering evidence of what each student knows, understands, and can do, usually through exams or graded assignments.

Chasm - tough to bridge differences between perspectives, particularly on politics and culture.

Curriculum - refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view of the student's experiences in terms of the educator's or school's instructional goals.

Delineate - to describe or portray something precisely, often with the purpose of differentiating or setting it apart from other topics of discussion.

Demographics - statistical data relating to the population and particular groups within it.

Mandate - (noun) the authority to carry out a policy or course of action, regarded as given by the electorate to a candidate or party that is victorious in an election.

Mandate - (verb) to officially give orders to people or institutions to act or change existing procedures in alignment with particular goals.

Pacing - in teaching, the amount of time given to a range of subjects so that certain areas are covered in the specified timeframe.

Open Educational Resources (OER) - resources available online at no cost to teachers.

Variable - in social science, a named element, feature, or factor that can be researched for its relevance, impact, and importance.

Read for Understanding

New American History provides teachers and students with high-quality inquiry-based learning resources for students. We are often also a source for pre-service teacher education and in-service professional learning. In 2024 the American Historical Association (AHA) released a landmark report entitled American Lesson Plan: Teaching US History in Secondary Schools. The main research questions revolved around how history is taught, who is making curricular decisions, and what kind of content is being taught - that is 'What Are Students Learning About Our Nation’s History?’. At issue, unsurprisingly, was whether there was any sense of “indoctrination” happening – i.e. are students getting a view of their nation’s history that is distorted and/or partisan? The basic finding was no. The report is also a good learning tool for educators to think about the current state of history education in America–what we are doing, and why and how.

In this Learning Resource, we help unpack some of the more interesting findings from the 200-page report. We offer them as a means to generate conversations and ideas on how we might best innovate and elevate the teaching and learning of American history, geography, and civics amongst teachers and administrators on the front lines making curriculum and decision-making policies and processes.

Note that we have not included a summary of the extensive discussion of historical attempts to control, legislate, or simply study history education in schools. Such discussion is interesting but has a marginal impact on today’s history teachers. If curious, do read pages 29 to 38.

Engage:

Why did the report happen, and what did it include?

Why did the report happen?

This report is the first comprehensive study of K-12 history education in the twenty-first century. The stated purpose was to create a clear, evidence-based picture of the K-12 history classroom in light of attacks on history instruction nationwide.

What did it include?

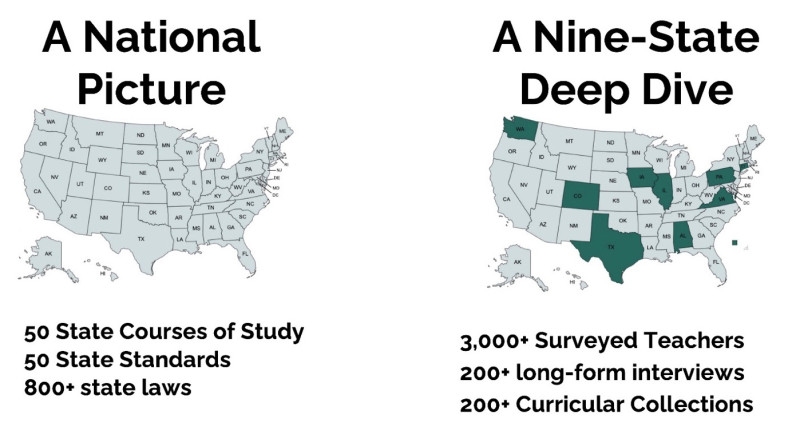

The report begins with a survey of state and district-level evidence, including surveys of classroom-level curriculum materials. Evidence came from both a national picture of state laws and standards and a deeper dive into district and teacher-level decisions and curricular content across nine regionally representative states.

What insights did the report gain?

The report highlights the following findings in the report’s Introduction (pp 9-13).:

- Common Ground

- Cold Fronts and Hot Spots in the Culture War

- Free Online Resources Outweigh Textbooks

- Testing Matters, for Better or for Worse

- Teachers Make [Almost All] Curricular Decisions

- Bad Questions Give Inquiry a Bad Name

- Calls For Help

Or, as the report’s online introduction states: “The resulting report provides a clear and evidence-based picture of the 21st-century history education landscape.”

You can watch an introductory video from a webinar where the research coordinator gives a good, short (5-minute) overview of the report here.

To introduce the report to teachers, we have divided it into Learning Resources that will unpack key findings and help generate thought and discussion around them. First, we will cover the initial sections: Contexts and National Patterns. Later, Learning Resources will cover the largest section: Curricular Decisions and lastly Curricular Content.

Explore:

What kind of research questions and methodologies were used in the report?

In Part 1, “Contexts”, the section discusses the research questions and methodology and provides antecedents and background for the study. Of note is a statement on page 12, that “the chasm between curriculum as written and curriculum as taught” makes broader generalizations implausible, especially around anecdotal complaints about history in schools.

The report claims in this section to be organized around three main questions, said to reflect the “complexity of curricular decision making” in the US: (p 19)

- What are American middle and secondary school students taught about US history?

Followed up with:

- Who decides what will be taught in US history?

- What sources, texts, and materials do teachers actually use when teaching US history?

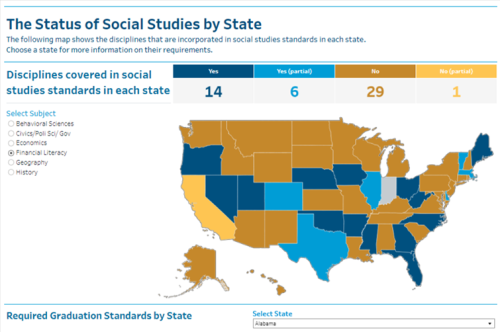

It is particularly striking that right up front the researchers found that curriculum very often differs quite widely from written - i.e. from state/district level standards - to on-the-ground teaching in classrooms. Past surveys and studies were noted, and of particular interest might be the American Institutes for Research (AIR) digital interactive dashboard of state standards, disciplinary coverage, graduation requirements, and assessment mandates (Published: March 27, 2023, Updated: June 4, 2024).

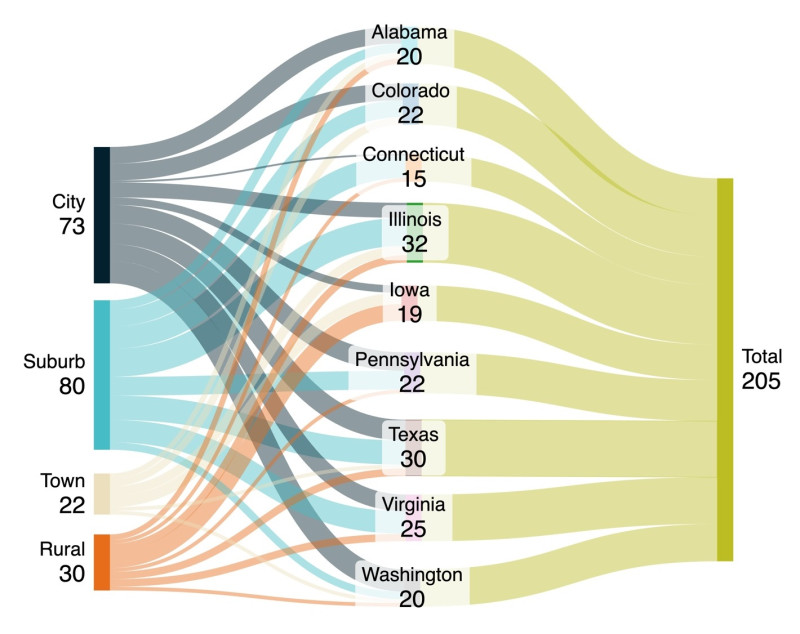

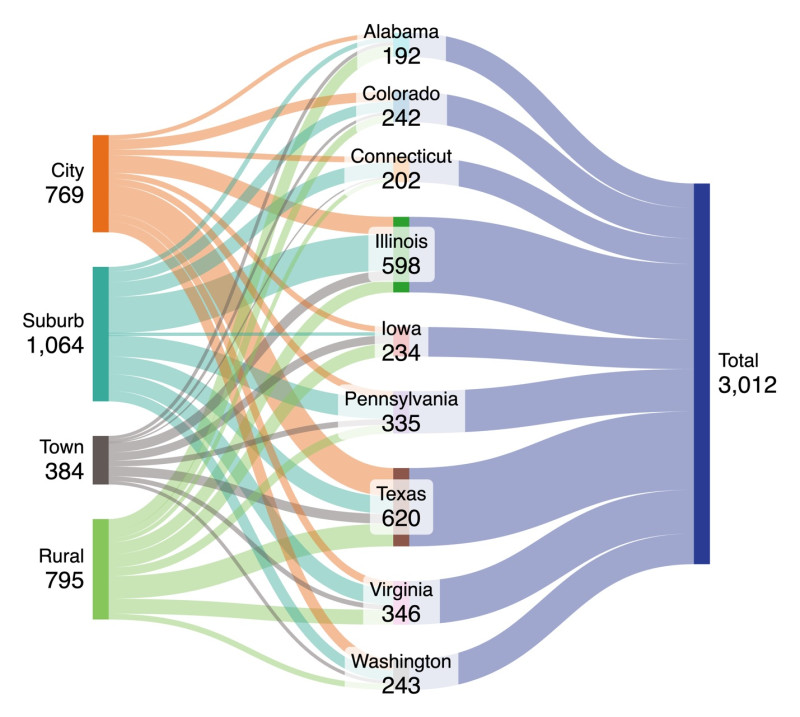

The AHA’s intent was to research and capture a “range of environments, both among states and within them”. (p 20) Nine states were chosen as survey subjects: Alabama, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. These follow the US Census designations of nine regions and provide “a mix of political, administrative, and social contexts affecting education”. (p 20)

At the state level, the report notes, agencies have limited control over curriculum unless they have standardized assessments. As part of their national research, the report created a database of state legislation (over 800 in all) affecting social studies across all 50 states mainly between 1980- 2022.

Noting that state-level documents are not necessarily useful for studying actual in-classroom curricula, the survey of district-level standards was helpful but not available for many districts due to the diversity of social studies staffing, or - for the most part - lack thereof. Teachers and administrators from the sample states were interviewed, with methodology detailed on pages 22-25. Regional patterns by state are shown in a graph (Figure 2, p 23). Special attention was paid to “capturing a mix of social and political environments within each sample state”. (p 23)

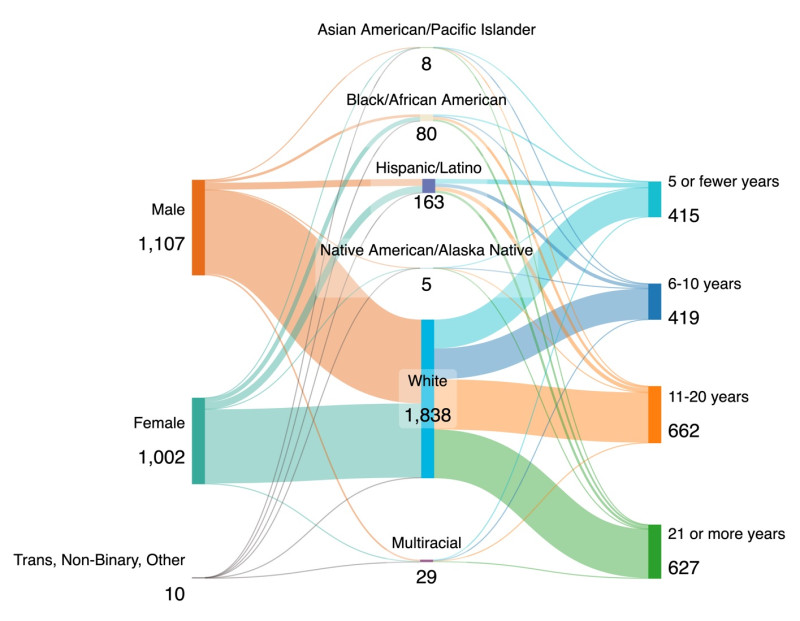

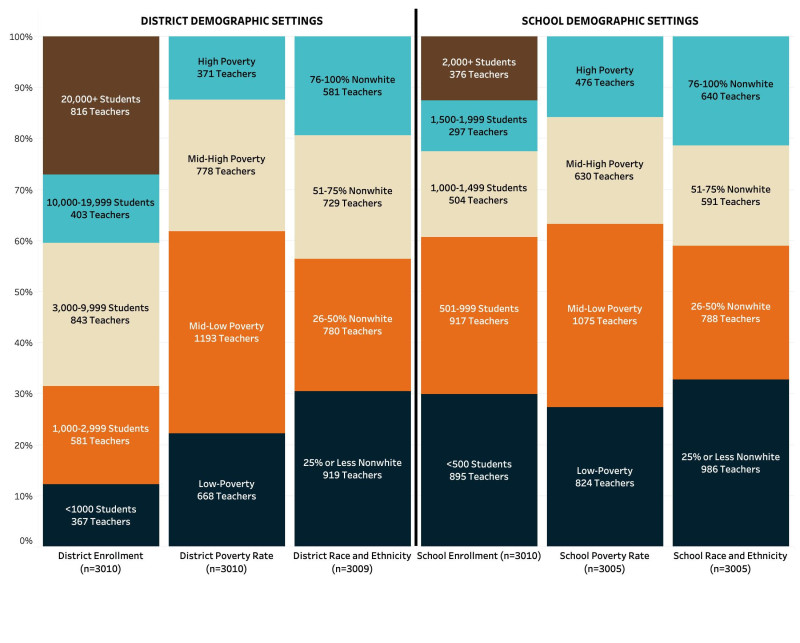

Finally, to get information about classroom-level practice and content, researchers interviewed and surveyed teachers and collected samples of teaching materials from the teachers themselves. An extensive detailed methodology for creating the survey, including how interviewees were chosen, is given (pp 25-27). The final count included over 200 interviewees and 3,000 survey participants. Demographics are detailed in the report’s Figures 3, 4 & 5.

Questions to consider:

- State-level legislation, district-level documents, and interviews, followed by teacher interviews, seem to leave out school principals. Responses appear to show that principals had some say in the curriculum - or attempted to - but are not listed as interviewees. How might that have affected the conclusions?

- What do you think of the mix of urban, suburban, town & rural?

- How do these locales differ in your state and how might that affect curricula?

- How did the researchers attempt to diversify the sample? Do the demographics seem diverse enough?

- Are the graphics, and/or data visualization, helpful? What might you have done differently?

- What kind of a community (urban, suburban, town, rural) do you serve? When you meet teachers who work in other environments, does their description of their workplace mostly match your experience? Or are you struck by distinct challenges or administrative conditions that they report to you?

Explain:

What were some of the findings on standards across the chosen states?

This section (Part 2 of the report, “National Patterns”) looks at the diversity of US history education across the states. The report notes that the structures around history education are a “patchwork” of curricula, assessment, and legislation - with trends as well as anomalies throughout the survey. The researchers studied institutional contexts at the state and national level, which eventually either shape local administrative and teaching decisions or - sometimes - do not impact much at all. Described as a “clutter of educational governance”, researchers nonetheless found consistencies in many areas. Most surprising was the finding that “a handful of states offer no state-level guidance or description of courses of study”. (p 48)

The detail found in graphs (not reproduced here) looks at state standards - or lack thereof - from grades K through 12. These include:

- The sequence of required and recommended courses in US history

- The scope of US history content coverage

- US history courses of study by grade level and state

Note that the survey delineated whether students were taught state history, United States history, or both, and at what grade levels.

State social studies standards tended to be fairly recent, mainly since 2000, but varied widely. Encouragingly they say that when a rationale for studying history was given, “preparation for participation in a democratic society is the common refrain”. (p 52) An explicit focus-centering inquiry, alongside federal policy emphasis on reading and writing skills, is said to be widely attributed to the National Council for Social Studies (NCSS) and their 2013 “C3 Framework”. This influence highlights the role of networking among teachers as well as administrators. Throughout the survey, teachers responded both with positive and negative comments on state agencies and standards. (See Table 1, p 53, for examples.) Documentation at the state level was found to be mixed - from the amount of guidance to the type of guidance to the clarity of the guidance.

Regarding the disparity in guidance or standards, researchers found the most obvious differences to be whether they were more skills or more content-focused. But there was good news here: ”By our count, 10 states emphasize skills to the exclusion of content, nine states hide skills beneath heavier content, and 31 choose a balance.” (p 54)

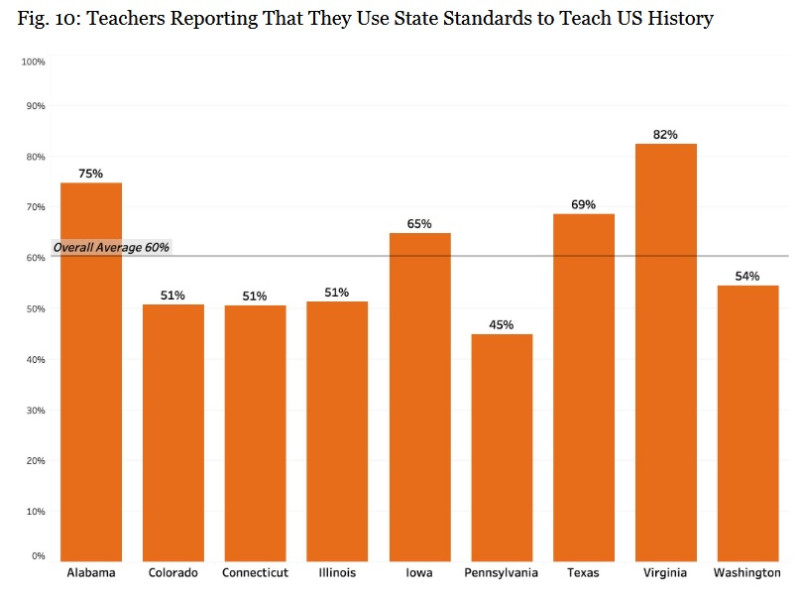

Surveyed as to whether they follow state standards, unsurprisingly teachers had mixed answers. Figure 10, shown below, breaks down results among the nine sets of teachers surveyed by state.

Discussion Points:

- Do you know your state’s - or district’s - standards? Are they easy to find?

- Do you follow the standards, if there are any, exactly?

- If you modify from your state or district standards, how much do you change your curriculum?

- Do you think the standards you work under are good, or do they need revising (or creating, if there are none)?

- Does anyone from your state education agency interact directly with you or someone in your division about social studies education?

Elaborate:

What were some of the findings on assessment and legislation across the chosen states?

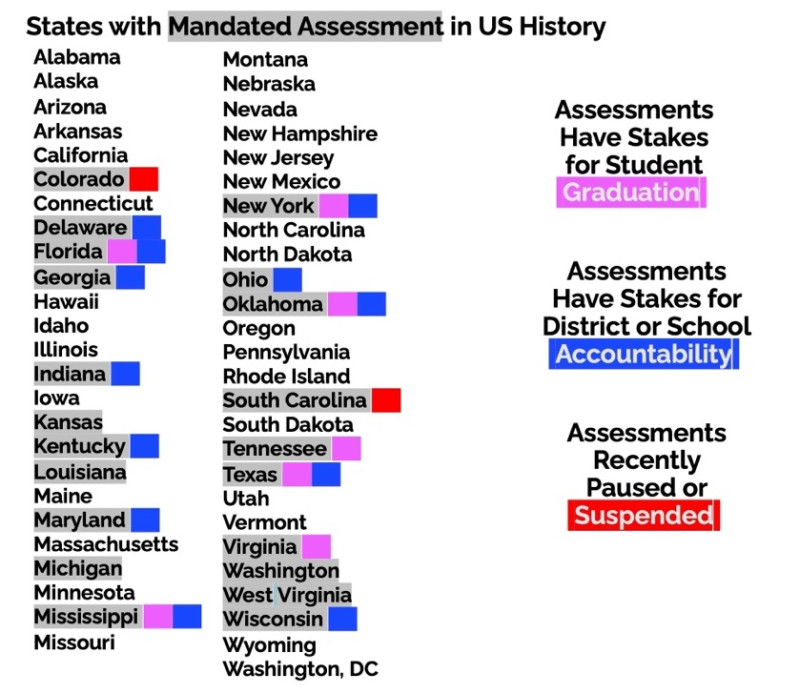

The further review of state standards in Part 2 was around assessment. As the study indicates, this is a decisive variable that impacts whether teachers are apt to follow standards, either from the state or district level. Current to the report, 21 states require “some” testing in US history. Of those, ten states test on content at least twice between grades K and 12. Notable, however, is the finding that “the general trend is away from standardized testing in social studies”. (p 58) See Figure 11, below, from p 59.

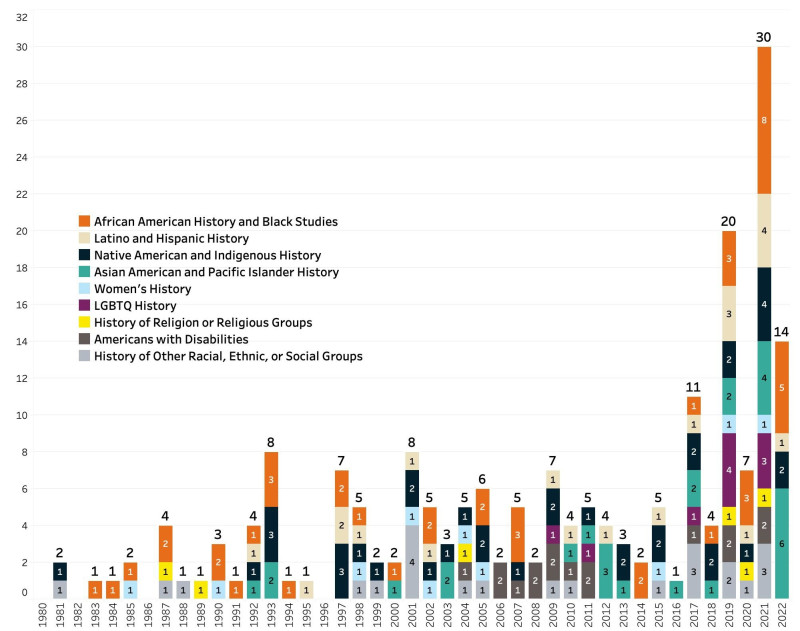

Finally, Part 2 looked at state legislation. As mentioned above, the researchers created a database from all 50 states, with legislation passed between 1980 to 2022. The total found was 808 individual acts of legislation, noting this is “extensive but not exhaustive” (p 61). That said, it helped create a broader picture of what priorities were being made at the state level. These acts were often identified as reactions to national education reform attempts, yet they could also be “hyper-local” reactions. Of note perhaps is that very specific historical figures or ethnic groups were mandated for study on special days or weeks. The examples ranged from Harriet Tubman to Harvey Milk and Hispanic to Francophone heritage, to name only a few. Some examples are shown below in Figure 14 from p 64.

Interestingly, lawmakers across the country have made politically or ideologically driven educational requirements across both spectrums, yet the most widespread requirement is for studying the nation’s founding documents, with 32 states having some kind of mandate (pp 65-66).

The conclusion of this section, however, notes that the examination of state history requirements simply does not indicate what US history content is being taught on the ground, or how it is being taught.

Part 2 discussion points might look like:

- Standardized testing means more alignment in curricula at district or state levels. Is that a good thing or not? Perhaps make a list of pros and cons.

- Do you think it is key to have statewide standards? Or is it better to stay local, within districts?

- If localities are those developing standards, might we end up with different content for urban, rural, town, or suburban students? Would that be appropriate or concerning?

- Might urban students need different standards than rural (for example), and if so, why?

Extend:

Watch or listen to the researchers discuss the AHA report.

The AHA has two posted videos you can watch to learn more from the researchers. One was a Zoom webinar + Q&A, and the other was a congressional briefing. Here we will give some highlights from the webinar, which was done to introduce and explain the report. (In Part II of this Learning Resource we will highlight comments from the congressional briefing.)

The webinar begins by discussing what the research coordinator, Nicholas Kryczka, suggests were his four main takeaways from compiling the report:

- Apathy not activism is the biggest problem;

- Decisions on curriculum happen on many different levels;

- The disappearing textbook & rise of online resources;

- History education is mostly fine, but support is still needed.

(These points were also discussed in the introductory video linked in the Engage section at the start of this Learning Resource.)

The early part of the video from about 7 minutes through about 11 minutes discusses much of what has been covered here in the first four Es. Of interest might be listening to the researchers talk about the research questions they asked (at 10:06).

Helpful too is anecdotal information that comes up in the webinar, for example from about 12:00 the discussion of standards and what teachers do and don’t like, as well as some interesting comments on the use - or absence - of assessment. This concludes the summary from Part 1 and 2 of the report.

Hereafter, the video discusses Parts 3 and 4, which are covered in our Part II Learning Resource. Watching this part of the video gives a preview of that content.

From around 15:00 there is a discussion on curricular direction received by teachers. Note that this portion of the webinar uses graphs of data that are not included in the PDF report because they were updated later. For correct data see Figure 15 on p 70 of the report, which is covered in Part 2 of this pair of Learning Resources.

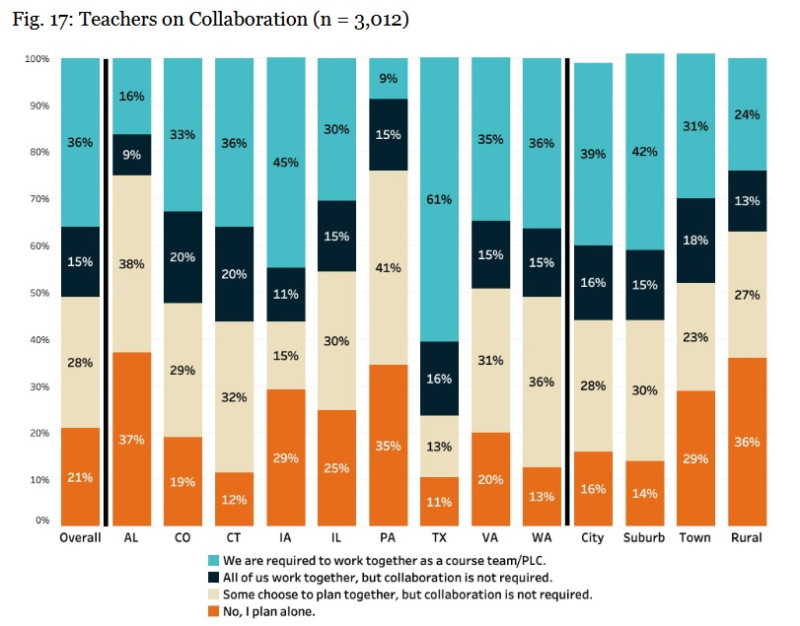

A discussion on collaboration between teachers follows, with some different graphics from those published, again because they were updated. Here is Figure 17 (p 78) which replaced the pie chart “Surveyed Teachers on Collaboration” at 17:40:

From 17:45 the discussion shifts to what materials teachers are using and where they come from. As noted in one of the four takeaway points in the introductory video, textbooks are used infrequently by comparison with materials teachers design themselves or obtain online. Again, this is covered in the next Learning Resource but it may be worth watching for a preview of the topic.

There is some good discussion about online resources beginning around 19:00, but in particular a bit more about two of the most popular of those resources. This starts at 19:30 and is especially worth watching or listening if you do not know much about the Stanford History Education Group (formerly SHEG, now the Digital Inquiry Group, or DIG) or Crash Course History (YouTube). Note this part includes a graph that was updated in the final report. (Refer for “Reported Familiarity with SHEG” to Figure 26, p 93 in the report.)

Further discussion (from shortly after 21:00) then covers Part 4, Curricular Content. This is divided by topics in U.S. History. Some points emphasized included:

- Materials were collected that were both used by teachers or that teachers were told to use.

- Content appraisal was key, however, the report does not “celebrate or indict” the material, it simply attempts to cover what is being taught.

- From about 25:00 there is a “quick tour” of all the topics covered: Native American History; The Founding Era; Westward Expansion; Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction; Industry, Capital, and Labor The Civil Rights Movement.

Again the discussion emphasizes (28:50) that they are not faulting the materials or content, and have found that if there is a fault in the content covered it is that of oversimplifying the topics rather than taking partisan views of them. They emphasize the importance of neutrality in teaching history (29:35).

From 31:00 the wrap-up discusses the issues that drove the report to be commissioned.

Finally, at 34:30 there is a Q&A period lasting almost 38 minutes.

Webinar discussion points might look like:

- Did you learn more from watching the explanations than simply reading the text of the Learning Resource?

- What questions were not asked that you would want to pose to the researchers?

- If you could survey teachers across different states would you ask the same questions? If not, what kinds of questions might you ask?

Citations:

American Historical Association, American Lesson Plan: Teaching US History in Secondary Schools (Washington, DC: American Historical Association, 2024).

Mapping the Landscape of Secondary US History Education team:

Research Coordinator: Nicholas Kryczka; Researchers: Whitney E. Barringer, Lauren Brand, Scot McFarlane; Project Directors: Brendan Gillis (2023–24); Alexandra F. Levy (2022–23); Sarah Jones Weicksel (2022).

Whitney E Barringer, Scot McFarlane, Nicholas Kryczka, Good Question: Right-Sizing Inquiry with History Teachers, The American Historical Review, Volume 129, Issue 3, September 2024, Pages 1116–1127, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhae290

Whitney E. Barringer, Lauren Brand, Nicholas Kryczka. No Such Thing as a Bad Question? AHA Perspectives on History, September 26, 2023. https://www.historians.org/perspectives-article/no-such-thing-as-a-bad-question-inquiry-based-learning-in-the-history-classroom-september-2023/

Part 2 of the series, Unpacking the AHA Report, may be found here:

View this Learning Resource as a Google Doc.